An insight into the impact of the cuts on some of the

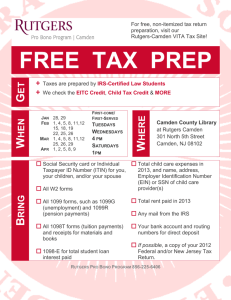

advertisement