C A R P

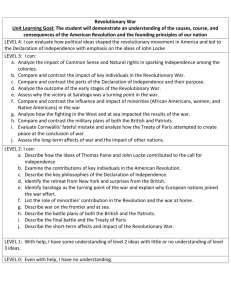

advertisement

Comparative Anthropologies of Revolutionary Politics CARP’s opening workshop Daryll Forde Seminar Room, UCL Anthropology Monday December 15th – Project presentation day 09.00 – 09.30 Tea & Coffee 09.30 – 10.15 Welcome and introduction to CARP Martin Holbraad (UCL, CARP) 10:15 – 11.00 I: Appearance, reality and secrecy in revolutions Igor Cherstich (UCL, CARP) Timothy Mitchell (Columbia) 11.00 – 11.15 Tea & Coffee 11.15 – 12.00 II: Mediated agencies – autonomy and heteronomy in revolution Martin Holbraad (UCL, CARP) Mike Rowlands (UCL) 12.00 – 12.45 III: Asceticism and the formation of revolutionary selves Martin Holbraad (UCL, CARP) Rane Willerslev (Aarhus) 12.45 – 13.45 Lunch 13.45 – 14.30 IV: Utopia, heterotopia and heterochronia Charlotte Loris-Rodionoff (UCL, CARP) Caroline Humphrey (Cambridge) 14.30 – 15.15 V: Visual and imaginative landscapes of revolution Myriam Lamrani (UCL, CARP) David Burrows (UCL, Slade School of Art) 15.15 – 15.30 Tea & Coffee 15.30 – 16.15 VI: Indigenous revolutionary horizons Nico Tassi (UCL, CARP) Eduardo Viveiros de Castro (Rio de Janeiro) 16.15 – 17.00 VII: Scaling revolution – grand schemes and everyday textures Alice Elliot (UCL, CARP/Leverhulme) Morten Axel Pedersen (Copenhagen) 17.00 – 18.00 Drinks 19.30 Workshop participants’ dinner Comparative Anthropologies of Revolutionary Politics Tuesday December 16th – Methodology and ethics day 09.00 – 09.30 Tea & Coffee 09.30 –11.00 Roundtable I (Chair: Igor Cherstich) Research heuristics: revolutionary politics and religious practice Martin Holbraad (UCL, CARP) Lucia Michelutti (UCL Anthropology) Nicola Miller (UCL History) Bruce Kapferer (Bergen) 11.00 – 11.15 Tea & Coffee 11.15 – 12.45 Roundtable II (Chair: Alice Elliot) Security and ethics: fieldwork, violence, surveillance Timothy Mitchell (Columbia) Caroline Humphrey (Cambridge) Mike Rowlands (UCL Anthropology) Lucia Michelutti (UCL Anthropology) 12.45 – 13.45 Lunch 14.00 – 15.30 Roundtable III (Chair: Nico Tassi) Comparative anthropologies: connecting the fields Bruce Kapferer (Bergen) Nicola Miller (UCL History) David Burrows (UCL, Slade) Eduardo Viveiros de Castro (Rio de Janeiro) 15.30 – 15.45 Tea & Coffee 15.45 – 17.00 Summing up and reflections Martin Holbraad & all 17.00 – late Drinks! Comparative Anthropologies of Revolutionary Politics SESSION ABSTRACTS Day 1: the petals I: Appearance, reality and secrecy in revolutionary contexts Often Revolutions are presented as attempts to make the invisible visible. The revolutionary effort is described as a desire to reveal what lies behind the veneer of appearance (hidden forms of exploitation, inequality disguised as social convention) in order to establish a new regime of truth. In the Marxist tradition this aspect of the revolutionary process has been analysed through the dichotomy Ideology/ Reality, and by offering different ways to unpack the relationship between the two. In this session (and more broadly in CARP), we reflect on these dynamics, but we also look at ways in which revolutions create multi-layered and ever-changing understandings of what counts as ‘appearance’ or ‘reality’. We ask ourselves what kind of demands does this economy of appearance and reality make on the revolutionary subject, how does it contribute to his/her articulation. We also consider the apparent paradoxes that characterise this phenomenon: how revolutionary governments created around notions of truthfulness and clarity make use of secret services, concealment and mystery. In doing so we deal with complex phenomena like propaganda, but we also look at secrecy both as a way to conceal reality and as tool to monitor (and therefore to disclose) reality. II: Mediated Agencies - Autonomy and Heteronomy in Revolution The force of revolution, as a mighty current that takes hold of its actors carrying them in its wake, appears to contradict the notion of a modern revolutionary subject as a self-bounded agent who is the author of its own deeds. This session focuses on notions of extraneous agency and the modes of mediation that accommodate their intervention on the individual subject. By looking at those zones of indiscernibility between the self and other, human and divine or citizen and the state, we question certain assumptions about the notion of self-bounded agency and the practices in which the distinction between particular forms of heteronomous and Comparative Anthropologies of Revolutionary Politics autonomous agency come to close proximity to one another. To this end the session will focus on the implications of particular conceptualisation of power and agency as seen in certain religious practices and the modes of social action they arouse. III: Asceticism and the formation of revolutionary selves This session focuses on the ascetic demands that revolutions place upon the subjects that are involved in them. Its premise is that, at least in its canonically modern form, revolution is par excellence a political project invested in the formation of particular kinds of selves – the idea of the New Man, the notion that changing society must involve changing people’s political ‘consciousness’, the notion of revolutionary ‘vanguards’ or ‘cadres’ as particular kinds of people, and so on. Inasmuch as CARP is focused specifically on the ‘anthropologies’ that revolutionary politics entail, this focus on self-making goes to the heart of the project. Indeed, the original theological sense of the term – i.e. anthropology as the study of humans’ position in relation to God – is particularly suggestive. To the extent that revolutions involve a strong element of so-called ‘political theology’, examining analogies, contrasts and complex relationships between revolutionary and religious forms of self-making may tell us a lot about what is most deeply at stake in revolution as a distinctive manner of political action. IV: Utopia, Heterotopia, Heterochronia How do revolutions create alternative temporalities and spaces? Revolutions are often perceived as utopia or as generating utopic discourses, but they can also remodel space and time creating heterotopias and heterochronias. By recasting time and space, revolutionary politics on the one hand transform a territory and its history, i.e. the coordinates of any political entity, and on the other hand, they intimately reshape selves, for time and space can be seen as the inner coordinates of the self. Revolutions thus emerge from and in specific spaces (Tahrir square, la Commune, Kafranbel), and engender novel understandings of temporal horizons sometimes defined as a rupture with the pre-revolutionary past, a sacrifice of the present and a march towards a better future or following alternative revolutionary Comparative Anthropologies of Revolutionary Politics temporalities. This panel aims to question the importance of utopia, heterotopia and heterochronia in revolutionary projects: how does the reshaping of time and space challenge both politics and self-making? V: Imaginative Landscapes of (Post-)Revolution This session explores the visual and dreamlike representations that arise in (post)revolutionary contexts. In a close dialogue with visual culture, be it through things or through dreams, we explore how landscapes of imagination are generated and how they interact with socio-political reality. What happens when the perceived reality takes the form of an imagined utopia or dystopia? By opening a space to think about visual and spiritual imaginative landscapes, this session looks into the 'stuff' that (post)-revolutionary imaginaries and visions 'are made of'. VI: Indigenous revolutionary horizons The session explores how indigenous cosmological forms and ideas act as devices shaping revolutionary horizons and spaces, temporalities and transformations. From a modernist perspective, revolution has been imagined as a progressive transition to a new society with increasing freedom and/or equality and radically severed from a traditional order. In recent years, revolutions have been associated with political immaturity or as a localised resistance to transnational phenomena (i.e. global neoliberal policies). What we attempt to foreground here are indigenous conceptualizations of transformation/invention, political logics, but also proactive processes of continuity and appropriation in the definition of revolutionary politics. In other words, what happens to an eminently modern concept such as revolution when we think it through an indigenous order of things? VII: Grand schemes and everyday textures: scaling revolution At what scale should an ethnographic study of revolution take place? What scales of existence does revolution inflect, affect and (de)generate? And what ethnographic texture does revolution acquire at different scales of social and intimate life? In this session, we address the scale(s) of revolution. We focus in Comparative Anthropologies of Revolutionary Politics particular on revolution’s peculiar quality of permeating fundamentally different – qualitative and quantitative – scales at once, fastening them into complex relational constellations: the scale of the self and that of history, the scale of intimacy and that of political imagination, the scale of ordinary routines and of cosmological orders. In addressing the scales of revolution and their ethnographic textures, we reflect on how best to conceive of the shapes revolution acquires in people’s lives and in anthropological thought. Day 2: The roundtables I: Research heuristics – revolutionary politics and religious practice CARP focuses on revolutionary ‘anthropologies’ in the original theological sense of the term, charting revolutionary politics in relation to varying conceptions of what it is to be human, and of how the horizons of people’s lives are to be understood in relation to divine orders of different kinds. The connection between revolutions and religious phenomena is particularly important here, and provides the project’s prime heuristic and comparative focus. To get to the heart of revolution as a project of self-formation, we suggest, involves examining how revolutionary politics sits alongside religious practices of self-making (asceticism, initiation, sacrifice, ritual and moral strictures etc.). How do revolutions in turns compete with religious forms, presenting themselves as alternative projects of self-formation, or join forces with religious practice in all sorts of complex and qualified ways? The purpose of this panel is to adumbrate the methodological and analytical implications of this approach to revolutions. How do we link revolution and religion heuristically in the context of broader arguments about the relationship between political and religious forms as objects of anthropological inquiry? What do we gain and what might we lose in framing our project in terms of these connections and analogies? And what implications does this have for our ethnographic inquiries in the field? Comparative Anthropologies of Revolutionary Politics II: Security and ethics – fieldwork, violence, surveillance Doing field-work in countries that have experienced (or are experiencing) a revolution forces the anthropologist to face specific ethical and methodological issues. In this section we want to discuss the practice of keeping a field-diary and the strategies of accessing the field. In particular, we want to ask the question: what kind of concerns should inform the anthropologist in carrying out these practices in a revolutionary context? How can the anthropologist grasp the unpredictable effervescence of revolution and at the same time guarantee the safety of his/her informants? And what about the anthropologist’s own safety? In trying to find possible answers to these questions we want to discuss issues of anonymity in ethnographic writing, the ethical dimension of writing about violence, and research strategies in contexts of surveillance and monitoring. The Anthropology of Revolution also forces the anthropologist to ask whether he/she is allowed to take sides, and how to deal with the tension between the researcher’s understanding of revolution and the informants’. III: Comparative anthropologies – connecting the fields Over the last decades an unprecedented geopolitical reconfiguration has affected traditional forms of hegemony and shaped new alliances transversal to the conventional political ‘axes’. The emergence of China as a world power has produced a process of geopolitical decentralization where the logic of politicoeconomic blocs with their annexed spheres of influence appears to have been superseded by a configuration of multipolar alliances and regional agreements in peripheral areas. In terms of CARP, this induces us to think of revolutionary politics as defined by the convergence of specific local issues and translocal alliances or temporalities (i.e. the Arab spring(s) or the New Left(s) in Latin America). Conventional political scholarship has often focused either on local issues or on translocal alliances, rarely concentrating on this overlap. How do we go about researching this convergence and overlap and how can we make sense of it? And ultimately, how does this affect the way we do comparative anthropology? Comparative Anthropologies of Revolutionary Politics IGOR CHERSTICH Libya: Sufism and state MARTIN HOLBRAAD ALICE ELLIOT Caribbean: Afro divination appearance, reality, secrecy Tunisia: migration and crisis agency and mediation scaling revolutions POLITICAL RELIGIOUS the shapes of relations NICO TASSI Bolivia: cosmologies of transformation indigenous horizons PERSONAL visual and imaginative landscapes MYRIAM LAMRANI Mexico: popular saint worship MARTIN HOLBRAAD SOCIAL asceticism and the self Cuba: intellectuals and reading utopia, heterotopia, heterochronia Syrians in Turkey: revolutionary councils CHARLOTTE LORIS-RODIONOFF CARP’s core structure: the ‘flower’