Pathsways to school achievement in very preterm and full term children

advertisement

European Journal ofPsvcliolog}' of Education

2004. Vol. XIX, nU, 385-406

'O2004.J.S.P.A,

Pathsways to school achievement in very preterm

and full term children

Wolfgang Schneider

University ofWiirzburg. Germany

Dieter Wolke

Jacobs Foundation, Zurich, Switzerland

Matthias Schlagmiiller

University of Wurzburg, Germany

Renate Meyer

University ofKonstanz. Germany

Individual differences in academic success were investigated in a

geographically defined whole-population sample of very preterm

children with a gestational age of less than 32 weeks or a birth weight

of less than 1500 gm. The sample consisted of 264 verv preterm

children (75.6% of German-speaking survivors) and 264 controls

matched for gender, socioeconomic status, marital status and age of

mother, who were studied from birth. The present analyses focused on

the impact of cognitive skills assessed at ages 6 and 8 on academic

success at the age 13. IQ scores, prereading skills, reading, spelling,

and math performance assessed during the last kindergarten year and

again at the end of Grade 2 were used as predictors of academic

success in early adolescence. Differences between very preterm

children and controls in cognitive abilities already observed in earlier

assessments remained stable over time, with controls on average

performing more than half a standard deviation above the level of

preterm children. Preterm children also performed poorer on the

literacy measures and indicators of math performance. Multivariate

and causal modeling revealed different prediction patterns for the two

groups. Whereas IQ was particularly important for the prediction of

Research on this project was financially supported by a grant of the German Research Foundation (Deutsche

Forschungsgemcinschaft) to Wolfgang Schneider and Dieter Wolke (SCHN 315/15-1), We would like to thank Klaus

Riegel and Barbara Ohrt who sel up the Bavarian Longitudinal Study in the !980s. Furthermore, thanks are due to David

Bjorklund for his valuable comments on an earlier drafi of ihe manuscript and Marco Ennemoser for his assistance in

data analysis.

386

W. SCHNEIDER, D, WOLKE, M. SCHLAGMULLER, & R. MEYER

academic success in the pre-term sample, general IQ was less relevant

for the prediction of academic success in the control group. When

subgroups of at-risk children were formed according to birth weight

categories, we found that school problems were most pronounced for

children with extremely low birth weight (WOO gm and less).

Very preterm delivery is often related to a negative consequences such as brain insults

and pulmonary problems (cf,. Hack, Klein, & Taylor, 1995; Landry, Fletcher, Denson, &

Chapieski, 1993). Further adverse consequences include poorer mental and motor

development relative to term controls during the preschool and kindergarten years (Wolke,

1998; Skuse, 1999), For instance, meta-analyses of studies on the intellectual development of

very preterm and/or very-low-birthweight (VLBW) children have revealed that their IQs are

approximately 0.5 standard deviations below those of temi infants {e.g,, Aylward, Pfeiffer,

Wright, & Verhulst, 1989; Escobar, Littenberg, & Petitti, 1991; Omstein, Ohisson, Edmonds,

& Asztalos, 1991), Other developmental problems such as language delays as well as

articulation problems have also been noted to be more common in VLBW children (ef,,

Friedman & Sigman, 1992; Wolke & Meyer, 1999). It is still unclear whether these deficits

are due to damage and thus inhibition of. normal development in specific areas of the brain,

or related to general IQ deficits.

Most follow up studies of VLBW samples into the school-age years indicate continued

problems in early and middle childhood (cf. Hack et al., 1995; Taylor, Klein, Minich, &

Hack, 2000; Whitfield, Grunau, & Holsti, 1997, Wolke, Schulz, & Meyer, 2001). This

research .suggests that cognitive problems range from global mental impairment to subtle

weaknes.ses in specific neuropsychological domains, such as language, memory, executive

function, and visuo-niotor skills. Although there is some evidence that VLBW children may

have more marked impairments in the areas of visuo-spatial functioning and memory than in

the language domain, the overall pattem is not yet clear. Behavioral problems of VLBW

children include attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), as well as deficits in social

competence and adaptive behavior (e.g., Botting, Powls, & Cooke, 1997; Hille, den Ouden,

Saigal, Wolke, Lambert, Whitaker, Pinto-Matrin, Hoult, Meyer, Verloove-Vanhorick, &

Paneth, 2001; Sommerfelt, Ellertsen, & Markestad, 1993). Moreover, deficiencies in acadeniie

achievement sueh as reading skills and mathematics have been reported in several studies

(Hille, den Ouden, Bauer, Brand, & Verloove-Vanhorick, 1994; Ross, Lipper, & Auld, 1991;

Bhutta, Cleves, Casey, Cradock, & Anand, 2002). Given that the cognitive and behavioral

problems of VLBW children interfere with learning, there is reason to believe that their

academic problems accumulate with increasing age. In fact, several cross-sectional studies

have reported higher rates of special education and more pronounced learning difficulties in

older compared to younger samples of VLBW children (e.g., Wolke, 1997; McCormick,

Gortmaker, & Sobol, 1990; Zelkowitz, Papageorgiou, Zelazo, & Weiss, 1995),

The leaming difficulties lead to a relatively high number of VLBW children requiring

special education. For instance, Hille et al, (1994) found that many of their VLBW children

suffered from reading and spelling problems when tested at the age of about eight years, with a

large percentage (more than 20%) of these children located in special education settings.

Evidence from related studies in North America (Saigal, Szatmarl, Rosenbaum, Campbell, &

King, 1991; Whitfield et al, 1997) or across the Westem countries (Saigal, den Ouden, Wolke,

Hoult, Pameth, Streiner, Whitaker, & Pinto-Martin, 2003) suggest that the percentage of at-risk

children receiving some form of special education may be even higher, up to 45%. This is

considerably more than you would expect for the general child population in European countries.

For instance, in Germany, only about 4% of a given school age cohort receive special education.

There is also increasing evidence that the school-related problems of VLBW children

continue to be substantial in adolescence and do not seem to reduce over time (Botting, Powls,

Cooke, & Marlow, 1998; Cohen, Beckwith, Pamielee, Sigman, Asamow, & Espinosa, 1996;

Saigal, Hoult, Streiner, Stoskopf, & Rosenbaum, 2000; Taylor et al., 2000).

SCHOOL ACHIEVEMENT IN PRETERM AND FULL-TERM CHILDREN

387

The achievement problems may be even more pronounced for those preterm children

with extremely low birth weight (ELBW; 1000 g and less) or bom at extreme prematurity

(<28 weeks). Those studies that compared groups at differeut neonatal risk (i.e., ELBW

children and VLBW children whose birth weight ranged between 1000 and 1500 g) found that

ELBW participants were even more disadvantaged than their VLBW counterparts (e.g.,

Klebanov, Brooks-Gunn, & McCormick, 1994; Saigal et al., 2000; Taylor et al., 2000), and

that there was a substantial negative correlation (about -,50) between birth weight and the

number of academic problems identified in adolescence. For instance, Taylor et al. (2000)

reported that about 45% of the less than 750 g group were placed in special education

programs compared to 25% of the 750 g to 1499 g group, and 14% of the term children.

Subsequent comparisons of the three groups at middle school-age suggested that the

consequences of premature delivery and very low birth weight were as apparent at this

measurement point as at early school age. Rates of grade repetition, special school programs,

and severe achievement problems were more prevalent in the less than 750 g group than in the

two other groups. There was also evidence that the less than 750 g group developed at a

slower pace relative to the (wo higher birth weight groups, and that verbal leaming skills were

specifically impaired (see also Taylor, Minich, Klein, & Hack, in press). Most of these studies

also emphasized the importance of social risk factors, indicating that children from low SES

famiiies and/or unfavorable family background were particularly vulnerable (Botting et al.,

1998; Saigal et al., 2000), i,e,, the effects were additive (Wolke, Schutz, & Meyer, 2001).

In contrast, studies of larger or low-risk preterm infants have not reported significant

deterioration in academic behavior over time (e,g,, Schothorst & van Engeland, 1996), or

reported only weak relationships between language problems of at-risk children identified

during the preschool years and subsequent reading and spelling skills (Wcindrich, JennenSteinmetz, Laucht, Esser, & Schmidt, 2000).

The patterns of findings appear to suggest that school achievement is more severely

affected the lower the birth weight or gestational period is, and that these deficits are long

lasting. However, there are several shortcomings of earlier studies. Many previous

longitudinal studies included no control group, employed arbitrary criteria to define cognitive

impairment, were single-centered studies, and generally included only short follow-up periods

(see Wolke, Ratschlnski, Ohrt, & Riegel, 1994; Wolke & Schulz, 1999, for more details

regarding these problems). Unclear is whether writing, reading or mathematical achievement

deficiencies are specific skill deficits or are more often explained by general cognitive

impairment (i.e., low IQ), There is a distinct lack of prospective research on differences or

similarities in the causal pathways between early deficits in pre-reading skills, the acquisition

of literacy and later school outcome in neonatal at-risk children. There is plenty of evidence

that individual differences in phonological information processing skills such as phonological

awareness, verbal memory capacity, and processing speed predict reading and spelling

development in 'normal', that is, randomly selected samples (cf, Bryant, MacLean, &

Bradley, 1990; Schneider & Naslund, 1999; Wagner & Torgesen, 1987), However, it is still

uncertain whether the same mechanisms that produce leaming problems in term children also

cause reading and spelling deficiencies in VLBW children. Thus understanding possible

differences would have immediate implications for educational intervention strategies with

very pretcmi infants.

For instance, if it tums out that VLBW children's reading problems are mainly caused by

poor phonological processing skills and not that much by low [Q, then it would make sense to

use phonological training programs with these children before they enter elementary school.

Such training programs have been shown to be particularly effective during the last year of

kindergarten (for a review, see Bus & van Ijzendoorn, 1999). Given that in most eases

objective data on the risk status of VLBW children are available from birth on, it should be

rather easy to identify these children in kindergarten and select them for specific phonological

treatment. So specific educational intervention programs (and not only different kinds of

medical treatment) could prevent prematurily born children from developing reading and

spelling problems.

388

W. SCHNEIDER, D. WOLKE. M. SCHLAGMULLER, & R. MEYER

The present paper reports on a large longitudinal study that investigated the intellectual

abilities, self-concept, language comprehension and expression, prereading and academic

skills in a population of very preterm children, matched term controls, and a representative

sample of children in the same age cohort living in a geographically defined area in the south

of Germany. These children were followed from hirth and tested at the ages of 5 months, 20

months, 4;8, 6;3, and 8;5 years. Questionnaire information on the cognitive and social

development of the sample and their school performance was obtained when participants were

12 to 13 years old. Results obtained for ihe preschool period have been published elsewhere

(e.g., Wolke, Ratschinski, Ohrt, & Riegel, 1994; Wolke & Meyer, 1999). In this paper, we

explore developmental trends in school achievement focusing on reading and spelling

development and school achievement between the ages of 6 to 13 years.

The aims ofthe present study were:

1)

To investigate the size of differences in cognitive development, achievement and

scholastic outcome between extremely, very low birthweight and low birthweight

children and to estimate the impact of socioecomic factors.

2)

To assess the causal pathways between pre-reading (phonological) skills and the

acquisition of literacy. Specifically, do the same relationships between preschool

measures of phonological skills and early literacy hold for both the VLBW children

and the control sample?

3

To assess the impact of early biological and social risk factors and early school

achievement in explaining scholastic outcome at 13 years of age. Do the same

factors predict later poor school outcome in groups of high- versus low-risk very

pretemi and control children?

Method

The design of the Bavarian Longitudinal Study (BLS) has been described elsewhere in

detail (e.g., Riegel, Ohrt, Wolke, & Osterlund, 1995; Wolke et al., 1994) and will only be

briefly outlined here. Ait infants born alive in a geographically defined area in Southern

Bavaria (Germany) between February 1985 and March 1986 and who required admission to a

children's hospital within the first 10 days after birth comprised the target sample. During the

study period, 70,600 births were registered in the region. The inclusion criterion was met by

7,505 children (10.6% of all births). The at-risk population ranged from very ill preterm

infants to tenn infants who required only brief observation in the special eare units. In addition,

916 healthy infants receiving care in the normal postnatal wards in the same hospital centres

or adjacent to the children's hospital were recruited as control infants during the same period.

Samples

The following samples were included in the subsequent analyses:

Very preterm children. Ofthe 7,505 at-risk children, 560 were very pretenn (<32 weeks

gestation) or very low birthweight children (birthweight<1500 g; referred to as VLBW/VP

subsequently) (see Wolke & Meyer, 1999). This sample comprised virtually all (>99%)

VLBW/PV children boni during thi.s period in this region. Of these VLBW/VP children, 158

died during the initial hospitallsation, and another seven died belween discharge from hospital

and 6;3 years of age. Four parents gave no written informed consent for participation in the study.

Forty-two parents and children were not included in the study because they did not speak

German. The potential sample of survivors thus comprised 349 very pretenn children. Of these,

264 very pretenn children could still be assessed at the ages of 6 to 13 years. A comparison of

those children who dropped out during the course ofthe study with those who participated from 3

years onwards did not show any systematic differences (cf Wolke & Meyer, 1999).

SCHOOL ACHIEVEMENT IN PRETERM AND FULL-TERM CHILDREN

389

For several statistical analyses, the sample of very preterm children was further

subdivided in groups of extremely low birthweight (ELBW; less than 1000 g), very low

birthweight (VLBW; between 1000 and 1500 g) and low birthweight (LBW; between 1500

atid 2500 g and gestational age less than 32 weeks).

Control group. From the 916 term children who received care in the normal postnatal

wards, a comparison group of 264 children was group-matched to the 264 VLBW children

according to sex of child, family SES, marital status ofthe parents, and maternal age.

Normative sample. A normative sample representative ofthe total population of Bavarian

infants was drawn from the complete BLS sample. Five stratification variables for constituting

a representative sample were available from the Statistical Yearbook 1985 for Bavaria and the

Bavarian Perinatal and Neonatal Survey 1985. These were sex distribution of newborn infants

(51% male), size ofthe community the parents were inhabiting (>50,000 inhabitants=27%),

educational level of mothers giving birth in 1985 (basic education: 9 years or iess-14%;

moderate education: 10-12 years with passed final exams: 76%; completed high school or

university education: 10%), gestation at birth (<32 weeks^O.9%; 32-36 weeks=6%), and

whether the infant had been admitted to a children's hospital within the first 10 days of life

(10.6%). There were 311 children in the normative sample. This sample was solely studied to

determine cohort-speeifie and regional norms, such as means, SD's and cut-off points for

determining cognitive impairment.

Medical and psychological foUow-up data around birth and in preschool

Prenatal and neonatal assessments are described in more detail in Wolke, Ratschinski,

Ohrt, and Riegel (1994). Within the group of very pretenn children, the amount of biological

risk was assessed using the 'Duration ofTreatnient Index'. Daily assessments of level of care,

respiratory support, and neurological status such as mobility, muscle tone, and neurological

excitahility were conducted from the first day after birth. The 'Duration ofTreatnient Index'

was computed as the number of days until the infant reached a stable clinical state (Wolke et

al., 1994; Gutbrod, Wolke, Sochne, & Riegel, 2000). SES was computed as a weighted

composite score of maternal highest educational qualification, and occupation ofthe head of

family (Bauer, 1988). For the analyses presented in this article, however, a transformed

categorical measure was used (high, middle, and low SES). As part of a full neurological and

psychological assessment program, children's eognitive development was assessed at 5 and 20

months of age, corrected for prematurity with the Griffiths Scales of Babies Abilities (Brandt,

1983), and the Columbia Mental Maturity Scale (CMM; Burgemeister, Blum, & Lorge, 1972)

at 4 years 8 months chronological age.

The si.x-year assessment

The major aim of this assessment was to test children's cognitive and language skills

before they began elementary school (Wolke & Meyer, 1999). Ninety-four percent ofthe

children were still in kindergarten at the time of testing, and those who had entered school had

less than three months of schooling.

Cognitive status. Children's intelligence was assessed with the German version ofthe

Kauftnan Assessment Battery for Children (K-ABC; Kaufman & Kaufman, 1983; Melchers &

Preuss, 1991). This battery is based on neuropsychological and information-processing

theories of intellectual functioning. Intelligence is measured with the Mental Processing

Composite (MPC; eighl sublests), designed to test basic mental processes. The MPC is

subdivided in two further subscores, the simultaneous information processing score (SGD)

based on the results of five suhtests requiring the processing of several stimuli at the same

time, and the sequential information processing score (SED) based on three subtests that

390

W. SCHNEIDER, D. WOLKE, M. SCHLAGMULLER, & R. MEYER

require Ihe processing of individual stimuli one-by-one. The Achievement Score (AS)

includes three subtests measuring what has been learned by the child.

Language development. Four subtests were used from a German test battery for language

development (the Heidelberger Sprachentwicklungstest HSET; Grimm & Scholer, 199!). These

included the following subscales: plural-singular rules, correction of semantically inconsistent

sentences, sentence production, and understanding of grammatical structures. Standardized

scores (T-scores) are available for each subtest as well as for the total score of the four subtests.

Academic self-concept. The cognitive self-esteem scores of the Harter Pictorial Perceived

Competence Scale (Harter & Pike, 1984; Asendorpf & van Aken, 1993) were chosen to assess

academic self-concept. The cognitive competence subscale emphasized academic performance

(being smart, feeling good about one's performance). Each item was scored on a four-point

scale, where a score of 4 indicated the most competent, and a score of 1 the least competent.

Prereading skills. The ability to recognize and categorize sounds (phonological awareness)

has been found to be particularly predictive of later reading and spelling skills and difficulties

(cf, Bradley & Bryant, 1983; Goswami, 1990; Schneider, 1993; Schneider & Naslund, 1999),

even when controlling for social and environmental factors (Raz & Bryant, 1990). The phoneoddity task involves rhymes in which three of four words share a common phoneme and the child

has to detect the odd word (Bradley & Bryant, 1983), This can be problematic, however, because

children must retain four words in order to make a decision. Given that not all of the six-yearolds have a memory span of four words (see Schneider & Naslund, 1999), a modified phoneoddity measure was adapted for this study that makes fewer requirements on memory

(Skowronck & Marx, 1989), The rhyming task consisted of 18 word pairs, half of which rhymed.

The number of correctly identified rhyming and non-rhyming pairs was counted.

In the sound-to-word matching task, children had to repeat each given word, and then

indicate if a specific phoneme pronounced by the experimenter was included in the presented

word. For example, the experimenter presented the word "Auge" and asked children whether

it contained an "au" phoneme. Again, the number of correct responses was counted. Both the

rhyming and sound-to-word matching task items were presented from a standard prerecorded

tape to all children to control for possible differences in pronunciation by different

experimenters. Intemal consistency was high for both tasks (alpha's>.90).

The naming of numbers and letters assessed children's knowledge of the alphabet and the

number sequence 0 to 9, Children were instructed to read a row of letters (random order) and

to indicate those that they knew. Answers were judged correct if the child could name,

pronounce, or say a word that began with the letter. Similarly, the digits were presented and

the child asked to name them. The total number of correct answers was calculated separately

for the naming of letters and numbers.

The eight-year-assessment

This assessment took place when children were in the fmal period of second grade. Their

average age was 8 years and five months.

Intelligence and language development. Again, children's intelligence was assessed with

the German version of the K-ABC, A total IQ score (Mental Processing Component: MPC) as

well as the various subtest scores described above were used in the statistical analyses. Also,

the test battery for language development (HSET) described above was used at this

measurement point.

School achievement. The Zurich Reading Test (Grissemann, 2000) was used to assess

reading speed and the number of reading errors. In addition to this standardized test assessing

children's word decoding skills, a pseudoword reading test developed by Leon-Villagra and

Wolke (1993) was given. It has been repeatedly shown that poor readers experience particular

SCHOOL ACHIEVEMENT IN PRETERM AND FULL-TERM CHILDREN

391

problems with pseiidowords, whereas normal readers' performance does not differ

significantly as a function of word materials (i.e., meaningful words versus pseudowords; see

Schneider & Naslund, 1999; Winimer, 1996), Internal consistency for the pscudoword reading

test was sufficiently high (alpha=.9t),

A standardized spelling test {Diagnostischer Rechtschreibtest DRT 2; Muller, 1983) was

used to assess children's spelling competencies. This closed test required participants to fill in

single words dictated by the experimenter into sentences depicted on the test materials. The

numbers of orthographic errors served as the dependent variable.

Finally, a measure assessing mathematical competencies was provided which was

developed by Wolke and Leon-Villagra (1993) as a German adaptation of the test package by

Stigler, Lee, and Stevenson (1990), The three subtests Estimation of sizes. Reasoning, and

Visualization were highly correlated (>,40) and summarized in one scale (Math performance;

alpha=.93).

Self-concept. In addition to academic success, self-perceived academic competence was

assessed again using the German version of the Pictorial Scales of Perceived Competence

described above (Barter & Pike, 1984; Asendorpf & van Aken, 1993).

The 13-year assessment

Academic success. When participants were about 13 years of age, a questionnaire was

seni out to them as well as to their parents in order to obtain information on academic success

and changes in self esteem. The response rate was good: 76% of all surviving very preterm

participants and about 95% of the controls (and their parents) answered the questionnaires.

A complex procedure was developed to measure academic success taking into account

level of educational track and performance within each track based on end of school year

grades. This procedure had to acknowledge the fact that in German schools (Bavaria) a

selection procedure (educational tracking) takes place after Grade 4 (the last year of elementary

school). Those children with above average or average achievement scores move on either to

the high or middle educational tracks (Gymnasium or Rcalschule). Those children with belowaverage academic performance continue with the low educational track (Haup(schule), Finally,

children with particularly poor academic achievement may receive special education

(Sonderschule), The ranking scale depicting academic succes.s combined information on the

educational track status and academic performance within the particular educational track (as

indicated by grades in math and German). The highest score of 9 was given to those students

who not only attended the Gymnasium (highest track) but also were at the age-appropriate grade

level (Grade 7) and showed average or above average performance {i.e,, grade mean better than

average), A score of 8 was given to those Gymnasium students who attended the ageappropriate class level but whose performance was below the mean, etc. Finally, a score of 1

was given to students who had received special education throughout their sehool career.

Statistical analysis

In a first step, comparisons were made between the total sample of VLBW/VP children

and matched control groups. Analyses of variance were carried out to assess group differences.

In a second step, multiple regression analyses were run for both groups in order to investigate

the impact of social and cognitive variables assessed over the preschool and kindergarten years

on subsequent reading, spelling, and math performance at the end of second grade. More

comprehensive structural equation modeling was carried out next, with the aim of assessing the

roles of preceding noncognitive and cognitive measures for academic success measured at the

age of 13, Finally, the sample of very preterm children was further subdivided in comparison

groups that differed in birth weight. More specifically, a set of ANOVAs was conducted using

the subsamples of extremely low birthweight eliildren (ELBW; less than lOOOg), very low

birthweight children (VLBW; between 1000 and 1500 g), and low birthweight children (LBW;

392

W. SCHNEIDER. D, WOLKE. M, SCHLAGMULLER, & R. MEYER

more than 1500g and less than 2500g; gestational age less than 32 weeks) to investigate whether

differences in birthweight were associated with educational outcomes.

Results

Preliminary analyses revealed that there were no differences between the control group

and the normative sample for any of the variables under study. For the sake of simplicity, only

the control group data are used in the following analyses.

Table I gives the means and standard deviations for ali of the variables considered in

subsequent analyses, as a function of group membership. The table also indicates the

significance of group differences and their practical importance (effect size), using the eta

statistics. As can be seen from Table 1, group differences for all of the variables under study

were significant. Moreover, the majority of these differences were substantial, as indicated by

the effect sizes (eta scores). With a few exceptions, eta scores ranged between .5 and 1,

indicating that the mean differences between the VLBW children and the controls ranged

between half a standard deviation and a standard deviation for those variables, which reflects

moderate to strong effects.

Table I

Means and standard deviations for all of the variables considered in subsequent analyses, as

a function of group membership

VLBW

Variable

SES

Gri'mih's EQ (20 mths)

CMM7'-scorc(4;8yrs)

Language r-score (6;3 yrs)

Lener Knowledge (6;3 yrs)

Number Knowledge (6;3 yrs)

Phoneme Test (6;3 yrs)

Rhyming Task (6;3 yrs)

K-ABC Scale S1F(6;3 yrs)

K-ABC. Scale SlF(8;5yrsj

Zurich Reading(en-ors;8;5yrs)

Spelling test (errors; 8;5 yrs)

Mathematics lest (8;5 yrs)

Academic success (13 yrs)

Control

M

SD

M

SD

1.89

92,06

40,49

44,97

5.12

5,41

9.15

11,37

86,61

89,28

38,46

14,56

12,45

4.42

0.75

21.60

17.51

8,25

6,67

3,72

4,61

5,10

16,50

17,98

52.64

7.04

5,19

2,94

1.91

106.39

50.46

51,52

8,46

7,98

11,83

13.46

100.16

100.52

13.52

10,59

16,30

6.76

0.75

6,71

10.00

6,77

7,83

2,45

3,17

3,11

11,24

9,92

14,15

5,66

3,39

2,31

P<

n.s.

001

001

001

001

001

001

001

001

001

001

001

001

001

eta

0,03

1,01

0.72

0,47

0,46

0,83

0,69

0,51

0,98

0.81

0.75

0.63

0.90

0.83

The relative impact of biological and social risk factors on academic achievement

To assess the relative impacts of biological and social risk faetors on indicators of

cognitive and academic achievement at the age of 8 years, analyses of variance using group

membership (VLBW vs. control) and SES (low, middle, high) as independent variables were

carried out for IQ (K-ABC-MPC), reading (number of errors, Zurich reading test), spelling

(number of errors, DRT 2), and math (conceptual understanding - see Table 2).

For the IQ variable (MPC) there was a significant group effect, F(l,487)=68.9, p<.(i],

and also a reliable effect of SES, F(2,487)=8.8,/3<,01. As can be seen from Figure 1, effects

of SES were similar for the two group.s. However, the effects of premature birth were stronger

than effects of SES, given that low-SES control children performed better than high-SES

children at risk, /(142)^3.67,/)<.0L The group difference in mean IQ at age 8 was substantial

(about a standard deviation) and comparable to the differences found at earlier assessments

(Caughy, 1996; Landry, Smith, Miller-Loncar, & Swank, 1997; Sameroff, Seifer, Baldwin, &

Baldwin, 1993; Wolke et al., 1994; Wolke & Meyer, 1999). About 21,9% of the VLBW

children but only 2,3% of the controls showed serious intellectual deficiencies, with IQs more

than two standard deviations below the mean.

SCHOOL ACHIEVEMENT IN PRETERM AND FULL-TERM CHILDREN

393

no

105

100

95

- • - S E S high

- • -SES middle

-•-SES low

90

80

VLBW

Control

Group

Figure I. Results of an analysis of variance using group tnembership (VLBW vs. control) and

SES (low, middle, high) as independent variables and IQ (K-ABC total score; at age:

6;3 years) as dependent variable

The analysis of variance using reading errors at age 8 as Ihe dependent tiieasure yielded

significant effects of group, F( 1,485)^54,6, p<.0\, but no effect of SES, /^(2,485)-2.0,/j> 05

(Table 2). Again, control children outperformed VLBW children. The group by SES

interaction was not significant. Overall, the mean reading error difference between VLBW

children and controls was about three quarters of a standard deviation, thus indicating a

moderately strong effect. Fitidings for the spelling error variable were similar. Group membership .showed a main effect (F( 1,483)^46.2, / J < . 0 1 , but there was no effect of SES and no

interaction. The mean perfoniiance difference between the two groups was about two thirds of

a standard deviation, again indicating a moderately strong effect. Finally, an analysis of

variatice with group membership and SES as independent factors and math performance

(conceptual understanding) yielded slightly different results. Both group membership,

F(],490)-97.9,/?<.0l, and SES, f(2,490)-4.2,;?<.05 (Table 2), had a significant effect for the

group and SES variable, respectively. There was no significant interaction. Table 2 shows the

means and standard deviations oflhe three criterion variables as a function of group and SES.

Table 2

Means and standard deviations (in parentheses) of ihe three criterion variables assessed at

8:5 years, as a function of group and SES

VLBW

Control

Variable

SES low

SES tniddie

SES high

SES low

SES middle

SES high

Zurich Reading (errors; 8;5 yrs)

45.82

(55.55)

15,39

(7.01)

12,01

(5.52)

34,05

(48,09)

i4,66

(6,87)

12.62

(4.87)

36.74

(56.43)

13.40

(7.29)

12.75

(5,37)

15.77

(14.72)

11.01

(5.74)

15.31

(3,50)

13,78

(14,22)

10.77

(5.7 i)

16.42

(3.06)

9,97

(12,67)

9,67

(5,44)

17,48

(3.44)

Number of cnrors DRT 2 (8;5 yrs)

Mathematics test (8;5 yrs)

Prediction of school achievement at age 8. Multiple stepwise regression analyses were

run to explore the impact of biological risk, social background, and cognitive abilities assessed

during the preschool and kindergarten years on reading, spelling, and mathematics perfonnance

at the end of Grade 2. Data of both the VLBW and control children were simultaneously

entered in the regression analysis, and group membership was coded as a dummy variable.

Predictors used were SES, language developtnent (total score), intelligence (K-ABC total

score, assessed at age 6), letter and number knowledge at age 6, self-concept at age 6, as well

as rhyming and phoneme discrimination at age 6,

W. SCHNEIDER, D. WOLKE, M. SCHLAGMULLER, & R. MEYER

394

Table 3 shows the outcome of stepwise regression analyses carried out separately for

reading, spelling, and math. When reading errors in the Zurich Reading Test were used as

criterion variable, about 40% ofthe variance could be predicted by the intelligence variable

{K-ABC-MPC at 6 years) alone. In subsequent steps, rhyming skills and number knowledge

accounted for additional variance in the reading variable. Overall, about 50% ofthe variance

in reading errors was explained by this combination of predictor variables. Group membership

did not significantly contribute to the prediction.

Table 3

Results of stepwise regression analyses for age 8 data, separately for the criterion variables

reading, spelling, and math

Predictors

(a) Dependent variable: Reading {R^ coiTected: 0.50)

IQ

Rhyming

Number Knowledge

(b) Dependent variable: Spelling {R- correcled: 0.41)

Letter Knowledge

10

Number Knowledge

Rhyming

(c) Dependent variable: Math {R- corrected: 0.56)

IQ

Phoneme Knowledge

Number Knowledge

Group

Letter Knowledge

Beta

T

P<

.41

8.88

4.97

4.11

0.01

0.01

0.01

.13

5.93

4.80

4.75

2.96

O.OI

O.OI

O.OI

0.03

.52

.13

.11

.08

.08

12.15

3.09

2.80

2.24

2.04

0.01

0.01

0.01

0.05

0.05

.22

.17

.25

.23

.22

Similar findings were obtained for spelling. Here, letter knowledge, IQ, number

knowledge, and rhyming contributed to the prediction, explaining about 4 1 % ofthe variance

in the dependent variable. Again, group membership did not contribute to the prediction.

Finally, the stepwise regression analysis using mathematics performance as dependent

variable yielded different results. Here, IQ turned out to be a very powerful predictor,

accounting for about 45% of the variance. Adding phoneme and number knowledge further

improved model fit. In addition, group membership and letter knowledge contributed to the

prediction of math performance. Overall, 56% ofthe variance in math perfonnance could be

explained by these predictor variables.

Given that group tnembersliip was a significant predictor of math performance, separate

stepwise regression analyses were carried out as a function of this classification variable. Overall,

results for VLBW children were most impressive. IQ turned out to be a powerful predictor,

accounting for about 64% of the variance. Adding number knowledge further improved model

fit. In total, 67% ofthe variance in VLBW children's math performance could be explained by

these two predictor variables. In comparison, only about 23% of the variance in the control

children's math performance could be explained by the regression model, indicating that IQ,

letter knowledge, and SES assessed in kindergarten had the greatest predictive power.

Predietion of academic achievement at age 13. As can be seen from Table 1 {last row),

control children showed higher levels of academic achievement than VLBW children when

the two groups were compared at age 13. This difference was not only statistically significant

but also substantial, yielding a difference close to a standard deviation. Causal modeling using

latent variables (AMOS) was used to explore the importance ofthe kindergarten predictor

variables as well as that of academic achievement assessed in elementary school {i.e., at age 8)

for prediction of academic success at the age of 13.

SCHOOL ACHIEVEMENT IN PRETERM AND FULL-TERM CHILDREN

395

A sequential strategy was used to test the assumption that the same pattem of

interrelationships would hold across the two groups. In a first step of analysis, we explored

whether the same measurement model held across the two groups. This assumption had to be

rejected given that model fit was very poor (;j<.0001). In a second step, we tested a

simultaneous model that allowed for different measurement models across groups but assumed

that the structural relations among constructs (i.e., the path coefficients) should be equivalent

across the two groups. Again, model fit was suboptimal (/?<.OO1), indicating that the

simultaneous model did also not hold using such less strict assumptions. As a consequence, the

simultaneous model was rejected and independent (one sample) models were estimated next.

ln the initial model specified for VLBW children, individual differences in biological risk

and SES were used as exogenous variables, which were assumed to predict IQ and

phonological skills assessed during the last year of kindergarten. In tum, the kindergarten

measures should predict reading, spelling, and math performance assessed at the end of second

grade (i.e., age 8). The model also specified a significant impact ofthe latter variables on the

measure of academic success at the age of 13.

Initial model estimates indicated that the original model did not fit the data. A closer

inspection of modification indices showed that the inclusion ofthe biological risk variable as

exogenous factor caused estimation problems. To improve model fit, the model was re-speeified,

and the biological risk variable was omitted. The resulting causal model is depicted in Figure

2. As can be seen from this figure, SES at birth had a moderate impact on IQ assessed at age

6. In ttu-n, IQ had a substantial effect on phonological awareness in kindergarten and also

strongly predicted math performance at age 8. IQ did not directly influence reading but had a

substantial indirect effect via phonological awareness. In comparison, the IQ effect on spelling

was insignificant and thus was omitted from Figure 2. Interestingly, phonological awareness

in kindergarten had a very strong impact on both reading and spelling assessed at the end of

second grade, explaining considerable amounts of variance in these constructs (67% and 76%

for reading and spelling, respectively). The three school achievement measures assessed at age 8

(i.e., reading, spelling, and math) had moderate but reliable effects on academic success

measured at the age of 13. Overall, about 64% ofthe variance in the academic success

measure could be explained by this model.

76

Figure 2. Structural equation model showing relationships between SES, IQ, phonological

awareness, and academic performance for the at-risk sample

Note. Chi-sqijare=196.21 (48 (//);;J=.OOO; n-t=.98; RMSR= 108.

396

W. SCHNEIDER, D, WOLKE, M, SCHLAGMULLER, & R, MEYER

Model fit was examined using the comparative fit index (CFI; Bentler, 1990) and the root

mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; Steiger, 2000), The CFI has a range from 0 to

1,0, with higher numbers representing better fit. CFI values larger than .95 seem generally

acceptable. The RMSEA index provides a measure of misspecification per degree of freedom.

Values under .06 indicate relatively good fit between a hypothesized model and the observed

data (Hu & Bentler, 1998). The model fit indicators obtained for the preterm sample did not

fulfill each of these threshold values {CFI=,98; RMSREA=.1O) indicating that one should be

somewhat cautious when interpreting the causal model,

A similar model was specified for the matched control children (cf.. Figure 3). Overall,

the structure of path coefficients was similar to that obtained for the VLBW children, SES

assessed at birth had a somewhat stronger effect on IQ assessed at age 6 in this group than it

had for the VLBW children, IQ showed a strong impact on phonological awareness during the

last kindergarten year, and also had a moderately strong effect on math at the end of Grade 2.

IQ also had an indirect effect on reading via the phonological awareness variable. Again, the

effect of IQ on spelling was negligible and insignificant. Although all of the three school

achievement measures showed a significant effect on academic success at the age of 13 years,

spelling had the strongest impact. Overall, 42% of the variance in the academic success variable were explained by this model. The model estimated for the controi children yielded a data

fit similar to that specified for the VLBW children {CFI-.98, RMSREA=. 10).

49

Figure 3. Structural equation model showing relationships among SES, IQ, phonological

awareness, and academic performance for the control group

Note. Chi-square=l92.89

(48df);p=.O00: CFI^,9S:

RMSR^.107.

Comparisons among at-risk subsamples

More recent findings have indicated that children of extremely low birthweight {ELBW;

less than 1000 g) show poorer educational outcomes as compared to VLBW children, preterm

children with low birthweight (LBW; more than 1500 g), and term-born controls (e.g.,

Klebanov et a!,, 1994). A closer inspection of our biological risk sample showed that 57

participants belonged to the ELBW group, another 135 children to the VLBW group, whereas

72 children could be classified as members of the LBW group. The means and standard

SCHOOL ACHIEVEMENT IN PRETERM AND PULL-TERM CHILDREN

397

deviations of IQ and outcomes on various educational test measures are given in Table 4, as a

function of group niemhersliip.

Table 4

Means and standard deviations for relevant variables, as a function of at-risk subsamples and

control group

ELBW(l)

Variable

SES

Griffith's EQ {20 nnhs)

C M M T-score (4;8 yrs)

Language 7-score (6;3 yrs)

[.elter Knowledge (6;3 yrs)

NumlKT Know ledge (6;3 yrs)

I'lioncmi; Tesl (6;3 yrs)

Rhyming Task (6;3 yrs)

K-At3C. Scale S ; F ( 6 ; 3 yrs)

K-ABC. Scale SiF(8;5 yrs)

larter Scale cognition (6;3 yrs)

laner Scale cognition (8;5 yrs)

Zurich Reading (err; 8;5 yrs)

Spelling lest (errors; 8;5 yrs)

Mathematics test (8;5 yrs)

Academic success (13 yrs)

VLBW (2)

LBW (3)

control

M

SD

M

SD

M

SD

M

SD

1.89

82.76

34.29

44.88

4.46

4.94

7.13

9.26

77.46

79.38

3.05

2.88

65.12

17.46

9.38

3.12

0.82

25.72

18.77

8.19

6.57

3.94

4.92

5.67

I6.B1

19.80

.55

.53

66.88

6.87

5.38

2.81

1.85

91.64

39.56

4S.O0

4.59

5.47

9.50

11.81

88.48

89.89

3.07

3.22

35.38

14.71

12.75

4.21

0.72

21.84

17.02

7.70

6.13

3.60

4.40

4.96

15.29

16.76

.51

.45

48.99

6.73

4.93

2.78

1.9

99.93

46.86

50.44

6.67

5.67

10.07

!2.32

90.57

96.67

3,03

3.31

21.59

11.76

14.59

5.85

0.78

13.53

15.55

8.57

7.53

3.79

4.34

4.38

15.90

14.57

.48

.41

34.73

6.76

4.24

2.78

1.91

106.39

50.46

51.52

8.46

7.98

11.83

13.46

100.16

100.52

3.22

3.45

13.52

10.59

16.30

6.76

0.75

6.71

10.00

6.77

7.83

2.45

3.17

3.11

11.24

9.92

.42

.40

14.15

5.66

3.39

2.31

SNK-Test

1-2

1-3

2-3

•

••

*

•

•

•

*

•

•

•

••

•

•

**

•

•

•

•

•

•

*

•

*

Note.

Several analyses of variance were carried out using group membership as independent

factor and IQ measures, language ability, and prereading measures as dependent variables.

Effects of group membership were significant for all ofthe IQ measures depicted in Table 4

(all/3's<.OO5). Subsequent S(udent-Newman-Keuls (SNK) tests revealed that ELBW children

performed significantly poorer than VLBW children on these measures, who in turn were

outperfonned by the LBW children. Although control children tended to perform better than

the LBW children, IQ differences were not significant. A significant main effect of group

membership was also found for the HSET language test, F(3,479)=6.56, /?<.002). Subsequent

SNK tests showed that ELBW children performed significantly worse than all of the other

groups, and that VLBW children were outperformed by both the LBW and the control children,

which did not differ from each other. Furthermore, significant effects of group membership on

results ofthe phoneme test and the rhyming task were found, F(3,479)=6.18,/J<.002, and

F{3,479)=5.99, /X.003, respectively. Again SNK tests showed that the ELBW children

performed poorest on both of these measures. On both tasks, the two other at-risk groups

performed significantly better than the ELBW children, but did not differ from each other.

Control chiidren performed best on these tasks, and significantly better than the three

remaining groups.

Another set of analyses of varianee were carried out for the educational outcome

measures assessed at the ages of 8 and 13 to compare performance of the three at-risk

subgroups with that of the term-born eonfrols. The analysis using group membership as

independent factor and reading (number of errors, Zurich reading test) as dependent measure

yielded a significant group effeet, F{3,479)=34.31, p<.Q I. Subsequent Student-Newman-Keuls

(SNK) tests revealed that the controi children and the LBW group differed significantly from

the VLBW group, which in turn performed significantly better than the ELBW group. A

similar ANOVA carried out for spelling as dependent variable yielded a main effect of group,

f(3,479)=23.65,;?<.01. Post hoc SNK tests showed that all ofthe subgroups differed reliably

from each other: the control children performed best, followed by the LBW, VLBW, and

ELBW groups, respectively. The ANOVA carried out for math performanee at age 8 yielded

comparable results, F(3,479)=48.05,/J<.OI. Again, subsequent SNK tests revealed that the

W, SCHNEIDER, D. WOLKE, M, SCHLAGMULLER, & R, MEYER

398

control group performed best, followed by the LBW, VLBW, and ELBW groups, respectively.

Finally, a similar analysis of variance using group as independent factor and academic success

at the age of 13 as dependent variable indicated that the pattern of findings obtained for the

early elementary school years was replicated. There was a reliable group effect,

F(3,527)=49.41, /X.Ol. Subsequent SNK tests showed that all of the four groups differed

significantly from each other, with the control group and the ELBW children forming the

extremes.

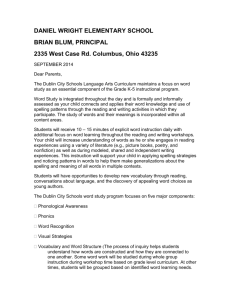

An interesting finding concerned the development of academic self-concept in the

various groups, A repeated measurement analysis of variance using group membership as

independent factor and academic self-concept assessed at the ages of 6 and 8 years as

dependent variable revealed significant effects of group, f(3,453)=16.27,/J<,OOI, and time,

F(i,453)^12,43,p<.00l. Overall, the control children's self-concept was better than that of the

at-risk children, and self-concept generally increased from time 1 to time 2. However, these

findings were qualified by a significant group x lime interaction, F(3,453)=5.72,p<.001 which

is illustrated in Figure 4. Subsequent SNK tests showed that increases over time were found

for all groups except for the ELBW children whose academic self-concept dropped between 6

and 8 years of age.

3.5

;ion

3.3

Harlei

c

oo

o

•

3.1

2.9

•

-•-LBW

• .«... V L B W

--•-ELBW

.4I_ control

2,7

2,5

8;5

6;3

Group

Figure I. Analysis of variance using group membership (ELBW, VLBW, LBW and control)

and age (6;3, 8;5) as independent variables and self-concept (Harter scale;

Cognition) as dependent variable

Discussion

The present study yielded coherent findings over time. First of all, the size of differences

in cognitive ability variables between the VLBW/PV and control children remained stable

over time. In an earlier comparative analysis of the present sample, Wolke and Meyer (1999)

already emphasized the fact that at 6 years of age, very preterm children performed more

poorly on all of the K-ABC subscale composites, with group differences in the simultaneous

infonnation processing component (SGD) heing particularly large (i,e., more than a standard

deviation). In comparison, group differences obtained for the sequential information

processing component (SED) were smaller, with preterm children on average performing half

a standard deviation below the level of the controls. By and large, this pattern of findings was

replicated in the assessment when children were 8 years of age. As can be seen from the last

column of Table 1, effect sizes (eta scores) obtained for the language and phonological

information processing variables assessed at the age of 6 years ranged between .5 and ,8,

indicating that the task-specific differences between preterm and control children were not

SCHOOL ACHIEVEMENT IN PRETERM AND FULL-TERM CHILDREN

399

only significant but also practically important. Similarly, pronounced group differences in

early literacy (i.e., number and letter knowledge) existed before children entered school.

Not surprisingly, these early group differences affected the acquisition of reading and

spelling skills at school. Control children outperformed the VLBW/VP children on all of the

literacy measures, with differences varying between a half to two thirds of a standard deviation.

Again, theses differences reflect substantial effects. They were most pronounced for

mathematics performance requiring visualization and reasoning (eta=.9O), indicating that

VLBW/VP children's school problems were not restricted lo the literacy domain. The present

analyses thus concur with fuidings from other longitudinal studies indicating that children bom

prematurely and with a lower birth weight are at increased risk of school failure (for a review, see

Taylor et al., 2000; Bhutta et al., 2002). They do not confirm findings that effects of early

biological risk on academic performance may not be strong (e.g., Schothorst & van Engeland,

1996; Weindrieh et al., 2000). Being born very pretcrni puts these children, as a group, at

statistically and practically higher risk for cognitive impaimient and schooling difficulties (Bhutta

et al., 2002; Wolke, 1998). Very low birth weight or very preterm birth is strongly predictive of

poor general cognitive abilities (IQ) and specifically, processing of simultaneous information

required in many life tasks such as in solving mathematical problems or dealing with the social

and behavioural demands of peer groups (Hille et al., 2001). Thus, within the VLBW/VP group,

cognitive processing in different domains was the major factor predicting school achievement.

Additional analyses of the impact of socio-economic status (SES) on cognitive abilities

and school perfomiance in the two groups revealed that this variable was infiuential, but that

there was no group by SES interaction. Overall, effects of SES were similar for VLBW/VP

and control children. As previously reviewed, the effects of very premature birth were

stronger than those of SES differences, given Ihat low-SES control children outperformed

high-SHS children at risk (Wolke, 1998). Very preterm children from low SES background are

thus at double jeopardy for poor scholastic outcome.

Another issue of interest that stimulated the present analyses was whether the same

structural relationships between preschool measures of phonological skills and early literacy

would hold for the groups of preterm and control children. Although findings from the various

analyses of variance consistently showed that mean level of group performance differed for

almost all of the variables considered, this does not necessarily imply that structural

relationships follow a different pattern. Indeed, findings from multiple stepwise regression

analyses with school performance measures as criterion variables revealed that prediction

patterns for the reading and spelling variables did not differ across groups. However, whereas

individual differences in IQ level were not that relevant for the prediction of math performance

in the control group, they were much more important for predicting math performance in the

group of VLBW/VP children. To our knowledge, similar analyses and results have not yet

been reported in the relevant literature. The fact that individual differences in biological risk

did not prove similarly important is likely due to the fact that IQ and biological risk were

intercorrelated. Thus neonatal risk and brain injury is refiected in the cognitive function

domain rather than transmitted by a separate route.

Another important research issue tackled in our study concerns the long-term prediction

of academic success in early adolescence based on preschool information and information on

academic performance in elementary school. Results of a sequential testing procedure

indicated that separate causal models had to be specified for the two subgroups.

The resulting model for the VLBW/VP children (depicted in Figure 2) shows a strong

impact of IQ assessed during the last kindergarten year on math performance, thus replicating

the outcome of the stepwise regression analyses. In addition, IQ had a substantial indirect

effect on reading which was mediated by phonological processing assessed at age 6. IQ

differences also predicted individual differences in phonological processing, which in tum had

a strong impact on reading (but not on math). In accord with the findings of the relevant

literature (e.g., Schneider & Naslund, 1999; Wagner & Torgesen, 1987), the literacy and math

variables had a direct effect on academic success in the secondary school system, accounting

for about 64% of the variance in this variable.

400

W. SCHNEIDER, D. WOLKE, M. SCHLAGMULLER, & R. MEYER

Overall, the results for the control group showed a similar causal pattern. For instance, it

seems remarkable that early SES differerence are not only related to IQ differences in both

samples but also have a direct effect on academic success which is not mediated by other

variables in the analyses. This finding suggests that there are other relevant factors not

specified in the model that are responsible for these SES effects e.g., attitudes, home,

environment and aspirations (e.g., Fergusson & Woodward, 1999; Schoon, Bynner, Joshi,

Parsons, Richard, & Sacker, 2002). The main difference between the two causal models

concerned the impact of early IQ on school performance, which was still moderately strong

for the control sample but not as pronounced as in the group of preterm children. In particular,

the impact of IQ differences on math performance was much stronger for the at-risk sample

than for the control children. Related to this, the model specified for the control children

explained less variance in the school performance variables, compared to the findings for the

preterm group. Again, this outcome confirms the findings from the regression analyses

described above, indicating that general cognitive difficulties are pervasive in VLBW/VP

children and less so in healthy full-temi children. Surprisingly, however, IQ differences also

predicted levels of phonological processing in both groups, a finding not in accord with those

reported in the relevant literature (e.g.. Bus & van Ijzendoorn, 1999; Schneider, Roth, &

Ennemoser, 2000).

Another deviation from typical findings concerned the predictor weight of the school

achievement measures. It was true for both groups that spelling performance at age 8

explained more variance in the academic success variable assessed at age 13 than proficiency

levels in reading. The latter finding may be due to idiosyncracies of the German school system,

where spelling performance is particularly important for selection processes taking place after

elementary school, that is, after Grade 4. Given that the VLBW/VP children generally operated

at a lower academic achievement level than the control children, spelling problems could have

been mainly responsible for class repetition and other problems at the secondary school level.

So far, we have only discussed implications of very premature birth and very low

birthweight combined. To remain consistent with earlier publications dealing with the Bavarian

study (e.g., Wolke & Meyer, 1999; Wolke et al., 1994; Hille et al., 2001), our at-risk sample

was further classified according to gestational age and not birth weight (even though we should

note that there is a considerable overlap in these two classification criteria). A final issue of

interest concerned the question whether differences in birth weight have an impact on

educational outcomes. Given that most recent studies on the issue relate levels of birth weight

with educational success, we re-classified our sample according to birth weight categories as

suggested by the WHO. This seemed important because current information on the effect of

birth weight on school function is limited by rather small samples from a single site, hospital, or

school district. Further concerns are raised when very low birth weight children are considered

as a whole and simply compared with normal birth weight groups, without considering heavier

low birth weight (1501 through 2500 g) children (cf., Klebanov et al., 1994). Our findings

indicate that individual differences in birth weight among at risk children do predict later

academic outcomes. School problems were most pronounced for the ELBW children, regardless

of measurement point, even though they also existed for the VLBW group. In comparison,

academic performance of the LBW children was more comparable to that of the control group

children. These findings are in accord with those of other longitudinal assessments (e.g.,

Klebanov et al., 1994; Saiga! et al., 2000), As previously proposed, biological risk does

distinguish children on the group level (i.e., ELBW have lower scores than VLBW or LBW

children). However on an individual level, the functional impairment in general cognitive ability

is the major predictor of school achievement. Thus those children who had severe neonatal

complications but these did not effect general cognitive abilities have a good chance of good

school adjustment. Previous reports of the Bavarian Longitudinal Study suggest that if the

VLBW children had not caught up within the first 20 months in their mental development and

head growth, the chances for adaptive cognitive development by 8.5 years were highly reduced

(Wolke, Schulz, & Meyer, 2001). Very preterm birth is a major reproductive risk that appears to

reduce the expression of genetic potential (Koeppen-Schomerus, Eley, Wolke, Gringras, &

SCHOOL ACHIEVEMENT IN PRETERM AND FULL-TERM CHILDREN

401

Plomin, 2000), Early recovery and intact general cognitive ability (on the functional level)

provides a good prediction of longer temi educational achievement in this group.

The inclusion oflhe academic self-concept variable indicates that the objective academie

differences are also reflected in altered self evaluations. We already knew from the relevant

literature that prematurily born children show lower levels of academic self-concept in

adoleseenee (cf., Cohen et al,, 1996), Our analyses revealed that at-risk children's academic

self concept was already generally lower than that of the matched controls from age 6 on, and

that different developmental trends could be observed as a function of risk subtype. The most

problematic trend was found for the ELBW children, whose academic self-concept deteriorated

significantly from age 6 to age 8. Although the two other at-risk groups tended to score lower

than the control children, the overall developmental trend paralleled that of the controls in that

their self-eoncept improved over time. The divergent pattern detected in case of the ELBW

children indicates that this group is in particular need of specific intervention.

Such a conclusion is substantiated by the findings for the prereading variables. The

ELBW children performed significantly worse than the other groups on both the phoneme and

rhyming tasks. A closer inspection of their scores on these tasks revealed that about 30% of

the ELBW children but only about 4% of the control children ranked below the 5th percentile.

Thus about one third of the ELBW children showed a severe risk regarding subsequent

reading and spelling acquisition in school. Using a more lenient criterion, more than 65% of

the BLBW children was classified into the lowest quartile of the distribution, which again

indicates a substantial risk. Although the situation was comparably better for the two other

at-risk groups, about one quarter of the LBW children and about 45% of the VLBW children

belonged to this at-risk category (i,e,, lowest 25%).

Overall, then, the academie situation appears difficult for prematurely bom children.

Although their lower IQ may limit the chances of cognitive interventions, the findings

nevertheless identify potential levers of where to intervene. As already noted above,

phonological training programs typically carried out during the last year of kindergarten have

been proven successful in groups of normal and at-risk children. Given the generally low

levels of phonological skills found for the VLBW children included in our analyses, these

children bom prematurely qualify as candidates for such educational intervention programs.

There is some evidence that these children may benefit from such programs, A recent training

study by Schneider. Roth, and Ennemoser (2000) revealed that the few prematurely bom

children in that sample (N=5) benelited as much as the rest of the sample from the training

procedure, and, as a consequence, did not develop academic problems in sehool. Thus,

whereas more general intervention programs mainly developed in the medical field had only

limited impact on altering at risk-children's general cognitive abilities (McCarton, BrooksGunn, Wallace, Bauer, Bennett, Bernabaum, Broyles, Casey, McCormick, Scott, Tyson,

Tonascia, & Meinert, 1997; APIP, 1998), it appears that more process-oriented training

programs in the field of edueational psychology couid help these children to overcome some

of their sehool problems, at least as far as reading and spelling is eoncemed.

References

Asciidoipf, J,. & vaii Akeii, M,A,G, (1993), Deutsche Version der Selbslkonzeptskalen von Haner [German version oflhe

HanerselTcontcpt scales], Zeitschriftfiir Entwickhmgspsychohgle undPndagogische Psychotogie, 25, 64-86.

Avon Premature Infant Project (APIP), (1998), Randomised Irial of parental support Tor families with very prelerm

cliildrtrn. Archives of Disease in Childhood - l''eial Neonatal Edition. 7'){ I), 4-11,

Aylward, G,P,, Pfeiffer. S,I., Wright, A,. & Verhulsl, S,J, (1989), Outcome studies oflow hirtli weight hifaiils puhlished

in the last decade: A nKia-ar\?t\y5\s. Journal of Pediatrics, 115, 515-520,

Bauer, A, (I988J, F.in Verfahren zur Messung des fiir das Bildungsverbalten relevanien So:ial-Status <BRSS) Oherarbcitete Fa.ssung [A measure assessing SBS in Germany, revised version], Frankfurt: Deutsches Institut (lir

Internationale PSdagogische Forschung.

402

W. SCHNEIDER, D, WOLKE, M. SCHLAGMULLER, & R, MEYER

Beniler, P.M, (1990), Comparaiive fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 107. 238-246.

Bhutta, A,T,. Cleves, M,A,, Casey. P,H-, Cradock. M.M,, & Anand, K.J, (2002). Cognitive and behavioral outcomes of

school-aged children who were bom preterm: A nieta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association.

28S{61728-737,

Botting, N,, Powls, A,. & Cooke. R,W,1, (1997), Atteiilicin ilefiuil hypcractivity disorders and other psychiatric outcomes

in very low birth wcighl children ai 13 year^. Journal of Devehpmeiital and Behaviorat Pediatrics. 38. 931-9i\.

Boiling, N,,Powls, A,, Cooke, R.W,, & Marlow, N, (1998), Cognitive and educational outcome of very-low-birthweight

children in early adolescence. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology; 40, 552-660,

Bradley, i.,,& Bryanl, P,E, (1983). Categorizing sounds and learning to r e a d - A causal connection,

Nature,30l,A\9-l\.

Brandt, I, (1983), Griffiths Entwicklungsskalen (GES) zur Beurteilung der Entwicklung in den ersten beiden

Lebensjahren [Griffith Developmenlal Scales for Ihe first two years of life], Weinheim; Beltz.

Bryant, P,, MacI.ean, M,, & Bradley, L, (1990), Rhyme, language, and children's reading. Applied

/ / , 237-252,

Psycbolinguistics,

Burgemeislcr, B,, Blum, t.,, & Lorge, J, (1972). Columbia Mental Maturity Scale. New York: Harcourl Brace

Jovanovich, Inc,

Bus. A,, & van Ijzendoorn, M, (1999), Phonological awareness and early reading, A mela-analysis of experimenial

training studies, Jtiumul of Educational P.sychology, 91.403-414,

Caughy. M.O. (1996), Health and environmental effects on the academic readiness of school-age children.

Developmental Psycholog}', 32, 515-522,

Cohen. S.E,, Beckwith, L,, Parmelee, A,H,, Sigman. M,, Asamow, R,, & fopinosa, M,P, (1996), Prediction of low and

nonnal school achievement in early adolescents born pretemv Journal qf Early Adolescence. 16.46-70.

Escobar, G,J,, Littenberg, B,, & Peltili, D,B, (1991), Outcome among surviving very low birthweight infants: A metaanalysis. Archives of the Disabled Child, 66, 204-21!

Fergusson, D,M,, & Woodward, [.,J, (1999), Maternal age and educational and psycho.-iocial outcomes in early

adulthood. Journal of Child Psychology' and Psychiatry. 40,479-489.

Friedman. S,L,. & Sigman, M,D. (1992). Past, present, and future directions in research on the development of low

birthweight children. In S,L. Friedman & M,D, Sigman (Eds.), The psychological development of tow birthweight

infants. New Jersey: Ablex Publishing Cooperation,

Goswami, U. (1990). A special link between rhyming skill and l!ie use of orthographic analogies by beginning readers.

Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 31, 301-311,

Grimm, il,. & SchOler. iL (1991), lieidelberger Sprachentwicktungstest (HSET). G5tlingen: Hogrefe.

Grissemann, H. ( 2000). Ziiricher Le.setest (ZLT; i5//i e(/,>. GOttingen: Hogrefe,

Gutbrod, T., Wolke, D,, Soehne, B,. & Riege!, K, (2000)- The effects of gestation and birthweighl on the growth and

development of very low birthweight small for gestational age infants: A matched group comparison. Archives of

Disease in Childhood Fetal and Neonatal Edition, 82. F208-F214,

Hack, M.. Klein, N., & Taylor. H, G,(1995), Long-term developmental outcomes of low birlh weight infants. The

Future of Children. 5, 176-196,

Harter, S,, & Pike, R, (1984), The pictorial scale of perceived competence and social acceptance for young children.

Child Development. 55. 1969-1982,

Hille, D,, Den Ouden, A,L,, Bauer, L,, Brand, R,, & Verloove-Vanhorick, S, (1994). School performance at nine years

of age in very premature and very low birth weight infanls: Perinatal risk factors and predictors at five years of

zgt. Journal of Pediatrics. 125, 426-434,

Hille, E,T.M,. den Ouden, A,I.,, Saigal, S,, Wolke. II., Lambert, M,. Whitaker, A,, Pinto-Matrin. J,A,. Hoult, L,, Meyer,

R,, Verloove-Vanhorick. S,P., & Paneth, N, (2001), Behavioural problems in children who weigh lOOOg or less at

birth in four countries. The Lancet. 357. 1641-1643,

Hu, L,, & Bentler. P.M, (1998), Fit indices in covariance sttucturai modeling: Sensitivity lo underparamelerized mode!

misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3. 424-453.

SCHOOL ACHIEVEMENT IN PRETERM AND FULL-TERM CHILDREN

403

Kaufman, A,, & Kaufman, N, (1983), Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance

Service,

Klebanov. P,K,, Brooks-Gunn, J,, & McCormick, M.C, (1994), School achievement and failure in very low birth weight

children. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 15. 248-256,

Koeppen-Schomerus, G,, Eley, T.C, Wolke, D,, Gringras, ?., & Plomin, R, (2000), The interadian of prematurity with

genetic and environmental influences on cognitive development of twins. The Journal of Pediatrics. 137. 527-533.

Landry, S,H,, Fletcher, J,M.. Denson, S,E., & Chapieski, M,L, (1993), Longitudinal outcome for low birth weight

infants: Effects of intravenlricular hemorrhage and bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Journal of Clinical and

E.xperiinental Neuropsychology, 15, 205-218.

Landry, S,H,, Smith, K,E,. Miller-Lonear, C,L,,& Swank, P,R. (1997), Predicting cognitive-language andsoeial growth

curves from early matema! behaviors in children al varying degrees of biological risk. Developmental P.sychology,

4^,1040-1053,

Leon-Villagra, J,, & Wolke, D, (1993), Pseudoword reading test. Munich: Unpublished Manniiscript,

McCartoii, CM,, Brooks-Gunn, J,, Wallace, 1,F,, Bauer. CR,. Bennett, F.C, Bemabaum, J,C, Broyles, S,, Casey, P.H,,

McCormick, M.C, Scott, D,T,, Tyson, J,, Tonascia. J,, & Meinert, C L , (1997), Results al 8 years of early

intervention for low-birth-weighl premature infants - The Infant Health and Development Program, Journal af

American Medical Association. 277, 126-132,

McCormick. M,. Gortmakcr. S,, & Sobol, A, (1990), Very low birth weight children: Behavior problems and school

diffieulty in a nationai sample. The Journal of Pediatrics, 117, 688-693,

Melchers, P,, & Preuss, U. (1991), K-ABC: Kaufman Assessment Batteiy for Children: Deutschsprachige

Frankfurt, AM: Swets & Zeitlinger,

Fassung.

Muller, R, (1983), Diagnostischer Rechtschreibtest DRT2 [Diagnostic spelling lesi for Grade 2]. Weinheim: Belt/,

Omstein, M,, Ohisson, A,, Edmonds, J,, & Asztalos, I;, (1991), Neonatal follow-up of very low birthweighl/cxtremly

low birthweight infants to school age: A critical overview./Jem Paediatrics Scandinavia. 80. 741-748,

Raz, R,S., & Bryant, P. (1990), Social background, phonological awareness and children's reading. British Journal of

Developmental Psychology. 8, 209-225,

Ricget, K,, Ohn, B,, Wolke, D,, & Osterlund, K, (1995), Die Entwicklung gefdhrdet geborener Kinder bis zumfiinften

Lebcnsjahr [The development of prematurely born children from bidh to age 5],Stullgan: Lnke,

Ross, 0 , . Lipper, E,, & Auld, P, (1991), Educational status and school-related abilities of very low birth weight

premature children. Pediatrics. 88, 1125-1134

Saigal, S,. I loult, L,A,, Streiner, D.L,, Stoskopf. B,L,, & Rosenbaum. P,L, (2000), School difficulties at adolescence in a

regional cohort of children who were extremely low birth weigh!. Pediatrics. 105, 325-331.

Saigal, S,, Szatmarl, P,, Rosenbaum, P,. Campbell, D,, & King, S, (1991), Cognitive abilities and school performance of

extremely low birth weight children and matched control children at age 8 years: A regional study. Journal of

Pediatrics. 118, 75\-760.

Saigal, S,, den Ouden, L,, Wolke, D,, Hoult, L,, Pameth, N, Streiner. D,, Whitaker, A,, & Pinto-Martin, J, (2003),

School-age outcomes in children who were extremely low birth weight from four international population-based

cohorts. Pediatrics. 112, 943-950,

Sameroff, A,J,, Seifer. R,, Baldwin. A., & Baldwin, C. (1993). Stability of inielligenee from preschool lo adolescence:

The influence of social risk-factors. Child Development, 64. 80-97,

Schneider, W. (1993), Introduction: The early prediction of reading and spelling, European Journal of Psychology of

Education,8, 199-203.

Schneider, W.. & NSslund, J.C. (1999), Impact of early phonological processing skills on reading and spelling in schooi: