Running Head: DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 1 Digital Engagement in D.C.:

Running Head: DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C.

Digital Engagement in D.C.:

How Nonprofits in the Nation’s Capital Use Social Media for Fundraising

By: Andrew Dean

Presented to the Faculty of the School of Communication in Partial Fulfillment of the

Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Arts in Strategic Communication

Supervisor: Dr. Paula Weissman

American University

April 23, 2015

1

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C.

© COPYRIGHT

Andrew Dean

2015 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

For permission to use any portion of this document, contact the author at andrewdecaro@gmail.com

2

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 3

Acknowledgements

First off, I’d like to thank Dr. Weissman for all of the advice she gave me as I pursued this project. I couldn’t imagine doing this without her guidance.

I’d also like to thank all of my classmates for their encouragement, as well as anyone who took the time to participate in my research. This project would not have happened without you.

Finally, I want to extend a special acknowledgement to my family for all of their love and support. Thanks to Mom, Zack, and Grandpa for always just being a phone call away, and to Nadia, Amanda, and everyone else in D.C. who inspired me along the way.

It’s been quite a ride.

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 4

Abstract

Social media has forever changed the ways in which nonprofit organizations (NPOs) interact with their constituents. Namely, it permits NPOs to communicate dialogically with key stakeholders; in turn building relationships that can result in increased audience participation like donating or volunteering. This study examined how nonprofits in the

Washington, D.C. area are using social media for audience engagement, including fundraising. It consisted of a series of in-depth interviews with 13 participants from 11 organizations across a range of disciplines. The study found that participants have mixed opinions on the effectiveness of using social media for fundraising, but there was almost unanimous agreement that social media is great for building relationships, raising awareness, and engaging target audiences. Further research is needed to explore this topic, as there is a significant lack of literature on using social media for fundraising.

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 5

Table of Contents

Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 6

Literature Review ........................................................................................................................... 9

Social Media and Engagement .................................................................................................... 9

Engagement and Fundraising .................................................................................................... 11

Nonprofits and Fundraising ....................................................................................................... 12

Nonprofits Using Social Media ................................................................................................. 13

Criticism of Online Engagement/ “Slacktivism” ....................................................................... 15

Dialogic Communication Theory .............................................................................................. 16

Conclusion ................................................................................................................................. 18

Research Questions ...................................................................................................................... 19

Method ........................................................................................................................................... 19

Participant Recruitment .............................................................................................................. 20

Procedures ................................................................................................................................. 22

Data Analysis ............................................................................................................................. 23

Results ............................................................................................................................................ 23

RQ1 ........................................................................................................................................... 24

RQ2 ........................................................................................................................................... 26

RQ3 ........................................................................................................................................... 27

RQ4 ........................................................................................................................................... 29

Discussion ...................................................................................................................................... 32

Key Findings ............................................................................................................................. 32

Nonprofits using social media for dialogic engagement .................................................. 29

Nonprofits using social media for fundraising ................................................................. 34

Concerns of “slacktivism” and engagement ..................................................................... 34

Conclusion ..................................................................................................................................... 36

Limitations ................................................................................................................................. 37

Notes for Future Research ......................................................................................................... 37

References .................................................................................................................................... 39

Appendices ................................................................................................................................... 42

Appendix 1: Informed Consent Document ................................................................................ 42

Appendix 2: Background Questionnaire ................................................................................... 44

Appendix 3: Interview Schedule ............................................................................................... 45

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 6

Introduction

Social media has made us more connected than ever before. From keeping up with family and friends to following the latest updates from brands and companies, these relatively new online platforms have allowed us to engage with each other in new ways.

In an article for Mashable, Soren Gordhamer (2009, para. 2) wrote, “social media communication tools have profoundly changed our lives and how we interact with one another and the world around us.” With this advent of new engagement opportunities comes the inevitable link to nonprofits looking to expand their outreach capabilities.

Given that social media is free to use, it seems like a great tool for nonprofit organizations (NPOs) to solicit target audiences for donations.

Many NPOs rely on fundraising to support their mission. Donors contribute to these organizations because they feel that NPOs are shaping society for the better. The

Foundation Center, one of the largest sources of information about philanthropy in the world, described philanthropy as “an engine for positive social change worldwide”

(“About Foundation Center”, n.d., para. 4). The Center for Philanthropy Studies at the

University of Basel (“Why Philanthropy”, n.d., para. 10) explained, “in a world, affected by individualism, philanthropy is the answer to why people support common welfare.”

Given the rise of social media it seems natural that nonprofits would flock to these resources to connect with potential donors. They connect organizations with vast numbers of constituents for little or no cost. But some research shows that nonprofits are, for some reason or another, reluctant to adopt these platforms as part of a larger engagement strategy. A content analysis of websites of charitable Swiss NPOs found that most nonprofits do not use online features like surveys, chat rooms, and forums. Only

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 7 one quarter of the websites included in the study had listed contact information for media relations (Ingenhoff & Koelling, 2009).

Some may argue that simply because there is the possibility for online engagement, it does not mean that organizations can expect any real world action. One school of thought calls passive online activism “slacktivism,” and can include anything from liking posts on Facebook, sharing Twitter and blog posts, and creating photos or videos on Instagram to show support for an issue or cause (Seay 2014). Despite research by Kristofferson, White, and Peloza (2014), which proved the existence of slacktivism, other researchers refuted the idea; saying that those who participated in online campaigns were actually more likely to engage in desired behavior, like volunteering (Paek, Hove,

Young, & Cole, 2013).

As more people use online platforms, nonprofit organizations may be missing out on opportunities to engage with current or potential donors. A study by the Pew Research

Center (2014) found that 74 percent of adults using the Internet are active on social media. Facebook is the most used, followed by LinkedIn, Pinterest, and Twitter. The sheer number of users on social media represents a great opportunity for NPOs to not only promote their agenda, but to dialogically communicate with potential donors.

This study examined how various types of Washington, D.C. based nonprofits are using social media to further their fundraising efforts, whether by explicitly soliciting donations for campaigns or for building relationships with publics that could result in financial return. Specifically, 13 representatives from 11 nonprofit organizations working in the fields of education, LGBT advocacy, labor rights advocacy, local community support, the arts, environmental protection, local hunger relief, and feminist and

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. reproductive rights in the D.C. area were interviewed to examine how, if at all, their organizations are using social media to supplement fundraising. The study aimed to find the extent to which these organizations are using social media for fundraising, which platforms they are using, and any results that they may have observed.

8

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 9

Literature Review

Social media allows organizations to engage with stakeholders dialogically, which helps build relationships. These relationships are important for nonprofits that depend on fundraising because research shows that engaged audiences are more likely to support an organization philanthropically. This philanthropic support can come in the form of smaller, annual gifts or larger, infrequent major gifts. The ways in which nonprofits use social media can determine how well they are engaging their target audiences and thus may provide a general idea of how likely target audiences are to donate to that particular

NPO. However, there is criticism of online activism because there is skepticism about whether or not it actually makes a difference in real life. This criticism is important because it allows us to evaluate whether or not online engagement actually produces real world engagement, like volunteering or donating to a nonprofit. Finally, the dialogic communication theory can explain how organizations can engage in dialogue with their publics in order to build relationships.

Social Media and Engagement

What begins online on social media can have much bigger impacts in the real world. Paek et al. (2013) found that if users participate in a campaign online, they are likely to partake in offline activity. Through an online survey of 73 participants, the researchers found that people who engage with a campaign on social media platforms (an organization’s blog, Facebook page, and Twitter account) are more likely to communicate to others about the campaign. They also are more likely to engage in desired behaviors, like volunteering. The study also discusses how Facebook in particular significantly impacts offline communication behavior, but control variables (sex, age,

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 10 race, education, residency and position related to the work of the campaign) may actually play a bigger role than social media. This may suggest that demographics may play a key role in online engagement (Paek et al., 2013).

Arguably the biggest strength of using social media is that it is interactive by design. Users are able to create, find, and share content with anyone in their networks, contributing to their online experience. With this ability to share content comes the concern about one’s image. This concern has been shown to contribute to online engagement. An online survey was distributed to 405 undergraduate college students to determine if a social networking site (SNS) would have a bigger effect on getting them to join a cause than a regular website (non-SNS). The study found that those who randomly viewed the SNS sites felt that their joining the cause was more likely to be viewed by others and therefore, positively influenced their decision to join the cause (Hyun & Mira,

2013).

One reason for this increased engagement is due to the fact that using social media can build relationships. This has not only been observed between individuals, but also between organizations and publics. Over the course of 40 in-depth interviews with employees of the American Red Cross, Briones, Kuch, Liu, and Jin (2011) found that social media offers the opportunity for two-way conversation which allows publics to voice their suggestions on how the organization can be improved. The Red Cross is also using social media to notify its donors and volunteers of events or times of crisis.

Additionally it is using social media to build relationships with the media. Briones et al.

(2011, p. 38) said “in summary research on online relationship management shows that

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 11 when practitioners understand the aspects of social networking sites, they can use them to engage and develop relationships with key publics.”

Engagement and Fundraising

Building positive relationships with donors is critical for NPOs to acquire financial support. Research has shown that long-term engagement with donors can result in greater donor satisfaction. In an electronic survey of 120 individual donors to a

California healthcare nonprofit, respondents were asked to evaluate their relationships with the organization. The results showed that donors with a longer relationship with the organization felt better; they felt more appreciated and believed that their gifts were being put to good use. Those donors with a longer relationship with the organization felt that the relationship was communal, and did not feel like they were being taken advantage of

(Waters, 2008).

Cultivating personal relationships with an organization’s donors can strengthen these positive relationships and is a major factor in getting potential donors to make a gift. Powers and Yaros (2013, p. 164) conducted a series of interviews with donors to nonprofit news organizations and discovered that “seven out of 21 respondents referenced personal connections as a motivating factor to donate.” Furthermore, almost half of respondents said that they felt more connected to their local news outlet or “felt a greater sense of investment” after becoming donors.

In addition to making donors feel more satisfied, research shows that nonprofits can receive more significant gifts when they build relationships with their donors. Cooks and Sokolic (2009) described a case where a foundation awarded a grant to a nonprofit every year for a few years. As this relationship between the foundation and the nonprofit

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 12 developed, the foundation became aware that the nonprofit needed more than just annual grants to continue operating. As a result, the foundation worked with the nonprofit to make a much larger gift. Cooks and Sokolic (2009, p. 141) concluded, “this case study illustrates the value of nurturing deep relationships…Because time was taken to meet, talk, and develop a relationship, this grant evolved into a different product than what was originally requested.”

Nonprofits and Fundraising

Most nonprofits would not be operating today if it were not for donors who help support their mission. Fundraising allows NPOs to continue to operate. In 2013, U.S. nonprofits received $335.17 billion dollars in donations, a 4.4 percent increase from the year before. Seventy-two percent of gifts came from individuals, 15 percent from foundations, 8 percent from bequests, and 5 percent from corporations. The areas most supported were religion, education, human services, and gifts to foundations (Giving

USA, 2014, p.1).

For nonprofits who conduct fundraising to support operations, they typically depend on two types of support, annual donations and major gifts. According to the

Minnesota Council of Nonprofits:

The Annual Fund sustains the organization and should be a primary strategy for stimulating the giving of unrestricted funds to allow the organization wide latitude in meeting its expenses. The Annual Fund is usually a donor’s first gift to an organization, unless they have made a gift through an event. The Annual Fund allows the organization to build a predictable base of support and provides a pool of proven donors that might be needed at some point, once they have made both

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 13 repeat and larger gifts, to become major donors. The donor database that is built over time will also serve as the primary information bank to be used in planning all fundraising programs for the organization. When an individual moves from an annual fund donor to a major donor will vary from organization to organization.

For some organizations major gifts might start at $1,000, while for larger institutions the major gift threshold might begin at $10,000. (“Annual Donations and Major Gifts”, n.d., para. 1)

On the other hand, there are larger, infrequent gifts known as major gifts. The

Minnesota Council of Nonprofits described these as:

Major gifts are infrequently given or asked for. When an organization asks for a major gift, it occurs in pre-meeting materials and in person or sometimes in a small group. Generally, it is from assets, not income, and is allocated to more targeted or distinct projects. Typically, a major gift is 10 to 20 times larger than an annual fund gift. While an annual fund give may be around $500, a major give is typically $5,000 - $10,000 based on the organization and its funders. On average, major gifts are 10 percent of the organization’s gifts, but 90 percent of total dollars raised. (“Annual Donations and Major Gifts”, n.d., para. 3)

Nonprofits Using Social Media

There is evidence to suggest that nonprofits are not utilizing online features, like social media, for dialogic communication. In one study, researchers conducted a content analysis of 134 charitable fundraising Swiss nonprofit organizations to see how they were using their websites to engage two key audiences: prospective donors and the media. The results showed that these NPOs are not taking full advantage of the potential of the

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 14

Internet to engage key audiences. The analysis found that most of the NPOs have specific contact information and don’t utilize technologies like chat rooms, forums, surveys, or call back options. Additionally, only a quarter of those from the content analysis had listed media relations contact information on the website (Ingenhoff & Koelling, 2009).

In another study, researchers examined 43 environmental NPOs in Canada to assess their use of social media for dialogic communication. They found that for the most part, the nonprofits included in the study were also not taking advantage of communication tools to dialogically engage their audiences. Greenberg and MacAulay

(2009) said:

NPOs should be leaders in using social technologies to grow and strengthen their networks. These are, after all, relationship- driven organizations: online communities and social media offer a new way of harnessing existing loyalty and passion. Yet, the data reported in this study suggest that this potential remains mostly untapped. (p. 74)

There are a few reasons to explain why nonprofits are not taking advantage of dialogic communication tools like social media. Greenberg and MacAulay (2009) suggested that:

Conversation, collaboration and other modes of two-way communication are time consuming and they do not always produce immediate or tangible results. Also, not every organization desires a relationship with their constituencies that is based on two-way, symmetrical communication. Many NPOs are strategically oriented—their communicative culture is thus geared less to achieving mutual understanding through an open- ended process of exchange, than upon securing

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 15 successful outcomes, whether that’s measured in terms of funds raised, policies changed or memberships/subscriptions sold.

On the other hand, Obar (2014) found that most Canadian nonprofits are adopting some social media platforms (mostly Facebook, Twitter, blogs, and YouTube) but that there is some reluctance among these NPOs to heavily rely on them. Over 150 representatives from 63 advocacy organizations in Canada were asked to determine how vastly social media has been adopted and implemented by these types of organizations in

Canada, and whether or not they feel that they offer new advantages. Most acknowledged that adopting social media had benefits like the ability for increasing outreach, offering feedback loops, and communicating more quickly. They also cited drawbacks to using social media such as the time and personnel needed to manage it, the fact that social media may not be good for advocacy, and that it needs to be studied more in order for it to be successfully used. In conclusion, while most acknowledged the introduction of some platforms has been beneficial, many responded that they are nervous about overcommitting to using the technologies.

Criticism of Online Engagement/ “Slacktivism”

A major criticism of online engagement is that the convenience of sharing information on the Internet has eliminated any real world engagement and instead has created passive online behavior that merely resembles activism. McCafferty (2011) said:

The conversation here is essentially positioned as a debate over activism versus slacktivism. The latter term refers to people who are happy to click a like button about a cause and may make other nominal, supportive gestures. But they’re

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 16 hardly inspired with the kind of emotional fire that forces a shift in public perception. (para. 1)

Morozov (2009) found that:

‘Slacktivism’ is an apt term to describe feel-good online activism that has zero political or social impact. It gives those who participate in ‘slacktivist’ campaigns an illusion of having a meaningful impact on the world without demanding anything more than joining a Facebook group. (para. 1)

Kristofferson et al. (2013) conducted a study in which they compared two types of support of an issue or case. Token support was defined as:

Online support such as liking or joining a page on Facebook. We refer to these types of behaviors as token support because they allow consumers to affiliate with a cause in ways that show their support to themselves or others, with little associated effort or cost. We contrast token support with meaningful support, which we define as consumer contributions that require a significant cost, effort, or behavior change in ways that make tangible contributions to the cause.

Examples of meaningful support include donating money and volunteering time and skills. (para. 2)

Over the course of five studies, Kristofferson et al. (2013) found that slacktivism exists, as public token support does not influence one’s decision to engage more significantly by providing a form of meaningful support.

Dialogic Communication Theory

Dialogic communication theory suggests that organizations that engage in substantial, two-way communication with its publics can build better relationships. Botan

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 17

(1993, p. 197) said “dialogue elevates publics to the status of communication equal with the organization.” In order for dialogic engagement to occur, three criteria must be met because there are basic concepts associated with engagement. According to Taylor and

Kent (2014, p. 387), “engagement assumes accessibility, presentness, and a willingness to interact.”

The ability to engage dialogically is arguably the most significant factor that distinguishes the Internet from other types of media. Taylor and Kent (1998) found that there were five important elements for engaging in productive dialogue with publics on the web. These included providing relevant content, making it easy to find information, generating return visits, conserving visit times, and providing a dialogic feedback loop, or a way for the audience to submit questions or concerns and receive responses. There are eight elements that comprise the dialogic feedback loop, “user-response, posting of new comments/issues, content sharing, opportunity to vote on issues, survey to voice opinion on issues, profile sharing, offers of regular information through email, and direct response to questions or comments from users.” (Lee 2014, p. 444)

Research shows the importance of utilizing all eight elements of the dialogic feedback loop. In a study conducted on a Facebook campaign about marriage in

Singapore, Lee (2014) found that the campaign only incorporated six out of the eight elements. The researchers believe that the exclusion of two elements, offers of regular information through email and direct response to questions or comments from users, might be a reason for the campaign’s low participation rate. In conclusion, this study demonstrates the importance of utilizing dialogic features of the social media.

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 18

Seltzer and Mitrook (2007) also found that blogs represent a great potential for organizations to engage with its publics. The researchers found that many of the dialogic principles that exist in traditional websites also exist in blogs. The only requirements here are that content should be conducted by someone familiar with the organization and have a good sense of the organization’s public relations strategy. Similarly, Taylor and Kent

(2014) briefly reference social media as a form of dialogic engagement. They mention that there is not much information currently available about social media and its role in relationship building between an organization and its publics.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the interactive nature of social media offers NPOs the opportunity to engage with target audiences. This interactive nature is based on a dialogic feedback loop, which allows target audiences to submit queries which organizations can then use to respond directly. This dialogue allows nonprofits to engage with target audiences in more meaningful ways to help build relationships.

As a result of building these relationships online, nonprofits are able to see real world results from their target audiences like volunteering or making a gift to the organization. Nonprofits depend on fundraising to operate, whether from a lot of smaller annual gifts or from a few major gifts. Despite the virtually unlimited opportunities to engage with stakeholders online, there is significant evidence that indicates that nonprofits are not effectively using social media to connect with donors. There is uncertainty among NPOs about how to best leverage the potential of the Internet to maximize return on investment.

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 19

Despite some nonprofits’ attempt to engage with target audiences on social media, there is criticism that suggests that merely engaging online has very little results in the real world. Known as “slacktivism”, this trend offers one point as to why social media fundraising may not be as effective as some NPOs may like to believe.

The dialogic communication theory can explain how nonprofits can build relationships by engaging in meaningful dialogue with target audiences. In order to engage dialogically, organizations need to be accessible, present, and willing to interact with their stakeholders (Taylor and Kent, 2014). Failure to do so will result in unsuccessful dialogic engagement, and thus limited relationship building.

Research Questions

RQ1: To what extent are the organizations using social media for fundraising?

RQ2: Which platforms are they are using to engage their audiences?

RQ3: What results, if any, have been observed so far?

RQ4: To what extent (and how) are organizations promoting dialogic communication via their social media interactions with audiences?

Method

For this study, I chose to conduct in-depth interviews with representatives from

NPOs in Washington, D.C. I selected in-depth interviews because they offer a certain degree of flexibility, in terms of capturing nuance and using probes to explore responses further. Keyton (2010, p. 284) suggested “interviews often provide the only opportunity to collect data on communication that cannot be directly observed.” Additionally, each organization that participated has slightly different objectives and tactics for both social media and fundraising. In-depth interviews allow the interviewer enough flexibility to

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 20 adapt to these changing objectives. Briones et al. (2011) used in-depth interviews in a similar fashion during their research of the American Red Cross’ use of social media to build relationships.

While they are good for capturing nuance, in-depth interviews have limitations.

For one, they can be largely unstructured and difficult to conduct. Keyton (2010) noted:

The interviewer has a general idea of what topics to cover but at the same time must draw on terminology, issues, and themes introduced into the conversation by the respondent. Thus to get the data needed to answer his or her research question, the researcher must have both theoretical and contextual knowledge as well as possess and be comfortable with a variety of communications skills. (p. 284)

Furthermore, results obtained are also not generalizable, there are time constraints with sitting down for an interview, and obtaining access to the desired individuals can be difficult.

Participant Recruitment

I interviewed representatives from several types of NPOs in Washington. The participants represented NPOs working in the areas of education, LGBT advocacy, labor rights advocacy, local community support, the arts, environmental protection, local hunger relief, and feminist and reproductive rights. I did not intentionally select these types of organizations; these nonprofits were the ones who responded to my requests for interviews. I spoke with 13 participants from 11 organizations. I used convenience and purposive sampling techniques to select certified, tax-exempt 501(c)(3) (or those with equivalent tax-exempt status) NPOs based in Washington, D.C. that were active on social media. I also reached out to my personal and professional contacts and arranged

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 21 interviews with these connections working for nonprofits in the Washington, D.C. area that were also active on social media.

The ideal organizations already had robust presences on social media, as evidenced by regular postings to multiple platforms and had mentions of previous campaigns with social media involvement, such as postings, blog posts, and retired hashtags, etc. However, few organizations met these criteria so I instead reached out to organizations with an active social media presence that featured an option to accept online donations by posting a button or a link on their website. The logic behind this was that if an organization were unable to accept online gifts via credit card then it would be extremely unlikely that they would be capable to accept gifts during a more robust social media fundraising campaign.

Once an organization was identified as being eligible to be included in the study, I conducted online research to determine the appropriate point of contact within that organization based on the employee’s title and the division of the organization. Ideally, I hoped to speak with the directors of communications, or the employee with the closest title, for these NPOs because senior employees were thought to be able to offer the most overarching perspective on the entire organization’s communications process. In the event that they were unavailable, unwilling to speak with me, or felt that they would not have the most knowledge on the subject, I asked them to recommend a colleague at the organization with knowledge of the social media communications and fundraising objectives.

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 22

Procedures

First, I selected participants based on which representatives from the NPOs agreed to be interviewed. Next, arrangements were made for the interview. I had hoped to conduct most of them in person but due to convenience, scheduling constraints, and the preference of the individual participants, most interviews were conducted over the phone.

Once the details for the interviews were arranged, I called the participants at the scheduled time or met them in person, obtained informed consent, and conducted the indepth interview. Informed consent was obtained through the use of the informed consent document (Appendix 1), which the participants reviewed and signed before the interviews began. In the cases of those participating by phone, the informed consent document was emailed to the participant to review before the interview started. The interview allotted a few minutes for the participant to ask any questions and give verbal consent on the tape. The participant was asked that they return the completed form by email or fax at the conclusion of the interview.

Before the interview, participants were asked to fill out a background questionnaire that gave a brief overview of their employment with the company, such as position title, length of time in this position, etc. (Appendix 2). In the cases of those participating by phone, the background questionnaire was read to participants and responses were recorded. Once the background questionnaire was completed, the interview was conducted based on the schedule (Appendix 3). The schedule aimed to answer the four research questions by inquiring about the organization’s existing social media presence, the integration of social media with fundraising campaigns, and what metrics have been observed. I recorded the interview audio on a cell phone’s proprietary

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 23 recording application for interviews conducted in person and used a third-party cell phone call recording application for interviews conducted over the phone. No participants objected to being recorded.

Data Analysis

Following the interviews, I transcribed the recordings and reconciled them with my handwritten notes. I looked for emerging patterns, trends, and commonalities among responses by the participants. Important patterns to look for included how many of the organizations that participated in the study actually used social media to supplement fundraising, the number of followers these NPOs had on each platform, and the staff involved in managing the social media and fundraising campaigns. Additionally, it was important to see how many of these NPOs had established metrics to evaluate the success of fundraising campaigns that incorporated social media and whether or not the organization felt that it had met these metrics. Upon completion of the analysis, I generated an overall assessment of how NPOs in Washington are using social media for fundraising.

Results

Overall, the nonprofits featured in this study were using social media for fundraising to some extent. Only one participant felt that he was not qualified to answer my questions and the interview ended early. Most participants thought that social media was great for engagement but not for soliciting gifts whereas one participant felt that the organization where she worked should focus all of their fundraising efforts online.

Another participant indicated that her organization has actually adapted their strategic

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 24 plan to incorporate social media fundraising because the leadership wants to expand their usage of it.

RQ1: To what extent are the organizations using social media for fundraising?

Generally, the participants are primarily adopting social media as a part of a larger fundraising strategy, including donor engagement, cultivation, solicitation, and stewardship. However, the extent to which the organizations used social media more heavily for different parts of the overall fundraising strategy differed drastically. For example, one participant was primarily concerned with engaging with members of the

NPO’s target audience who could potentially become donors down the road whereas another participant was very interested in using social media to directly solicit gifts from donors through crowdfunding campaigns.

The ways in which the NPOs in the study used social media depended greatly on the organization. Two organizations used social media to promote crowd funding campaigns. Six more used it to participate in a global online philanthropic event called

“Giving Tuesday.” A participant from an LGBT advocacy organization acknowledged a dedicated day of giving in which the organization conducted a massive online fundraising campaign for one day only. Two participants said that they participated in hyperlocal giving days, which allowed their organizations to receive online donations from local donors.

One participant from an LGBT advocacy nonprofit felt that his organization could do more with social media, but that their lagging web presence prevented him from doing so. A participant who worked at a museum was unsure how his organization used social media for fundraising. Additionally, social media was cited as a good way to raise

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 25 awareness about, and to encourage, end of year giving. Hashtags were shared as the common denominator among campaigns. One organization even included the hashtag from a crowd funding campaign on printed materials for the project because it became a part of the project’s brand.

Despite the overwhelming agreement by the participants in the study on social media’s potential to engage an organization’s target audiences, there was some debate regarding the effectiveness of using social media for fundraising. A participant from a major education nonprofit said that the use of social media to publicize a challenge gift was so influential that it might have helped reactivate lapsed donors. The participant who worked for a feminist and reproductive rights organization acknowledged that it is difficult to solicit donors on social media but she feels that it can help “funnel people into fundraising” and that any donors obtained via social media are donors that they might not have otherwise solicited. In terms of how the organization where she worked uses social media, she said that they are “diligent about using it for fundraising but are “just figuring out how it works with diverse audiences and projects.” The participant who worked at the environmental protection nonprofit pointed out that using social media for fundraising could be considered much less intrusive than a phone call solicitation from an NPO to a donor.

On the other hand, some participants felt that social media did not drive their audiences to make donations to the NPOs where they worked. One participant from an

LGBT advocacy group felt that social media does not directly raise money for his organization, but he has “seen an increase in funding” as a result of increased awareness among his publics about online fundraising. In addition, a participant representing an art

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 26 gallery (and the largest organization in the study) found that “social media does not drive donations, it drives engagement and it drives awareness of campaigns but the main thing that drives campaigns is email.”

RQ2: Which platforms are they using to engage their audiences?

Each organization used some combination of Facebook, Twitter, Instagram,

Storify, YouTube, Google+, Vine, Tumblr, LinkedIn, and Pinterest. Facebook and

Twitter were the most widely adopted platforms; every organization surveyed was using at least these two. Instagram was the next popular with seven organizations at least having an account, followed by YouTube and Google+. Six participants reported that their organizations were active on YouTube and five said that their NPOs had accounts on Google+. Vine, Tumblr, Pinterest, LinkedIn, and Storify were the least adopted with only a few participants mentioning that their NPOs were active on these social networks.

According to the participants in the study, only one or two staff members typically managed the social media presence for the NPOs where they worked. One organization, the art gallery, was able to recruit a task force of eight staff members who managed the entire social media presence, including a dedicated blog manager. The respondent from the local hunger relief nonprofit said that because only one person managed her organization’s social media presence, she would need more funding to hire more staff in order to more successfully engage her followers. The representative who worked at the major education nonprofit reported using social media to connect with

“social media ambassadors,” volunteers who shared content on their personal networks via content management software, during one of her organization’s campaigns.

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 27

The NPO with the largest number of followers had about 200,000 followers across all of its networks. The smallest was under 10,000. Also, the size of the organizations’ followers varied greatly not just between the NPOs but also between the different platforms operated by the same NPO. For example, the participant representing the education nonprofit reported that her organization had 8,478 followers on Facebook, but only 150 followers on Instagram. However three participants noted that the best platform to engage their audience on depended on the message and the audience that they wanted to reach.

Overwhelmingly, the platforms were updated frequently, with Twitter and

Facebook being used to share new content the most often. These were updated a few times a day, or at least a few times a week. Some platforms, like YouTube, Flickr, Vine, and Instagram were updated on an as needed basis. Three participants cited uploading videos to YouTube after events, but two of these three mentioned that they also generated proactive content on YouTube leading up to an event. Google+ was rarely mentioned.

RQ3: What results, if any, have been observed so far?

The results are mixed, depending on whether the participants were looking at the results in terms of concrete, financial totals or in terms of more abstract engagement like impressions, email opens, and shares on social media. In terms of dollars raised, the crowd funding campaigns were successful; both participants who cited using social media for crowd funding reported that those campaigns set metrics and goals before they launched and that the campaigns raised the amount of money that they had initially hoped. In terms of other engagement (volunteer recruitment or audience participation), the results were also successful, according to the participants.

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 28

The participant who worked at the education nonprofit noted that during her organization’s giving day, there was a direct correlation between the amount of activity on social media and the amount of gifts that came in. Her team observed that:

Social media activity was on a very steep incline until 1 or 2:00. Then there was a sharp drop off correlated with the giving, so I think we did not meet our goals we made when we set out to determine how many gifts were made. Whether or not we met our social media goals is harder to say. We didn’t know what to expect but I was very satisfied with the amount of activity during the day. When giving dropped off, social media activity did as well but…stayed at a mediocre pace throughout the rest of the day whereas the giving did not.

Despite a gradually declining pace of giving, she felt that the organization was successful in engaging its followers. She said that “I see that social media enthusiasm as a success even though I cannot directly correlate it to dollars raised…the giving day was, without a doubt, a win for engagement on social media.”

Seven participants reported having some type of metrics in place before campaigns, but most stated that these are not specific social media goals, for example establishing a threshold of obtaining 500 likes on a post. A large part of this being that the field is so new that many NPOs are organizing these types of campaigns for the first time. For example, participants from the education nonprofit and the art gallery noted that they almost were unsure what to expect before the campaign launched in terms of impressions so they instead analyzed the data through analytics software after the fact to determine the impressions, retweets, likes, favorites, and shares on any content that was generated. Two participants acknowledged using Salsa, a type of content management

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 29 software that can also serve as a donor database. The participant who worked at an environmental protection nonprofit had set goals for the number of people the NPO wanted to reach each month on Facebook.

All participants admitted that they plan to continue to use social media for fundraising going forward in some capacity. Two participants said that they will use it as part of a larger strategy, two are looking to expand their use of it, and one said that they are trying to determine the best way to incorporate it into their different programs and target audiences. A participant from the local hunger relief organization stressed the importance of hiring more staff as social media fundraising continues to develop. She said that growing her nonprofit’s use of social media for fundraising is “something we think about, the resources to do it is the issue…[We] plan to invest a little more every year as resources allow, but until social media tools begin to produce more it’s going to happen slowly.” She estimated that presently, social media fundraising brings in less than five percent of all donations to her organization.

RQ4: To what extent (and how) are organizations promoting dialogic communication via their social media interactions with audiences?

While its use for fundraising is mixed, most nonprofits are using social media to engage with audiences dialogically. Participants said that when their followers share, comment, like, favorite, and retweet content, they are participating in two-way communication. All participants said that their publics were receptive to the social media aspects, but those using it for fundraising cautioned against using it only for soliciting donors. A participant who worked at an art gallery said that the content needs to be

“educational and entertaining” in order to keep followers interested. The participant who

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 30 represented the feminist and reproductive rights nonprofit was even using social media to communicate with another target audience, fellow activists. She said that she will share anything that her target audiences are interested in and that she “[shares] other people’s content all the time. I break stories all the time, even if it’s not ours.”

Most participants said that Facebook was the best for connecting with publics. It was also named the most often as the best social media platform for fundraising. This is likely because of the large numbers of users on Facebook, as a participant from an LGBT advocacy organization noted, “our audience is mostly on Facebook….” A participant who worked at the environmental protection nonprofit said that Facebook was ideal for sharing more detailed information like an event.

However, some participants felt very strongly about Twitter. In particular, a participant representing a community support nonprofit felt that Facebook’s algorithm that requires users to pay for posts to appear at the top of newsfeeds made her less likely to use it during the day-to-day postings but acknowledged that she will pay for the extra visibility during campaigns. One of the participants from the art gallery ran a campaign that was designed to engage users exclusively on Twitter and felt that it worked well there. The participant who worked at an environmental protection nonprofit also felt that

Twitter worked the best for engaging her audience because “it allows conversations to occur in a public space” and that it creates a sense of activism because there is “more pressure on players to take action.”

Overall, participants noted that Google+ was the least useful; almost half of the respondents with a Google+ page said it has had the worst results for fundraising. A

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 31 participant who worked at a major nonprofit for the arts called it a “consistent letdown” and said that it “isn’t long for this world.”

Instagram also was cited as not being great for fundraising. The participant who worked at the education nonprofit felt that the technical capabilities of Instagram limited her use of the platform for fundraising. She said that because it does not permit users to embed links in posts, it is difficult to share content that links back to an online page where users can make a gift. A participant who worked at the environmental protection

NPO said that her organization was having a hard time getting followers to engage on

Instagram actively, saying that they were “engaging in a superficial way” by liking the posts and not doing much else. She described the activity by her organization’s followers on Instagram as “very passive instead of taking action.”

Overall, the participants agreed that social media is useful for engaging with publics and said that they used social networks in a few different ways. These uses ranged from sharing visual content, like images, to running crowd funding campaigns.

One participant who worked at an LGBT nonprofit cited social media as an excellent way to recruit volunteers for his organization. He used social media to put out positive information because he felt it helped build relationships and turned passive viewers into active participants.

Three participants were unsure about social media’s ability to help organizations cultivate relationships with its publics. A participant from the feminist and reproductive rights nonprofit said that her nonprofit lacked the internal resources she needed to cultivate relationships by performing simple tasks like responding to user queries, and said that “someone’s job could be responding to mentions all day.” The participant who

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 32 worked at a labor rights advocacy NPO said that social media does not cultivate deep relationships and finally, one participant from an LGBT organization acknowledged that it is “tricky” to do so.

Discussion

Key Findings

This study was conducted to help nonprofits determine how they can best engage their publics online in order to build meaningful relationships in hopes that these relationships would result in philanthropic support and ensure the longevity of the organization. The study found that the NPOs were using social media for fundraising in very different ways, which usually depended on the organization’s size and the demographics of their target audiences. However, almost all participants said that the nonprofits where they worked were using social media to engage their stakeholders to some degree. This engagement varied from simple dialogic engagement, like sharing content on social media, to more robust attempts to involve members of the target audiences in the organization’s activities. This more robust engagement included recruiting volunteers for events or asking followers to make a gift.

Nonprofits using social media for dialogic engagement. Dialogic communication theory states that organizations that engage with their publics in two-way communications have better relationships with key stakeholders. Botan (1993, p. 197) said, “dialogue elevates publics to the status of communication equal with the organization.” This study validates Botan’s claim because most participants felt that social media allowed the nonprofits where they worked to build direct relationships with their target audiences.

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 33

For the most part, the organizations in this study were not only active on social media, but they were enthusiastic about using it as another way to connect with their target audiences. This finding supports the characteristics of dialogic engagement expressed by Taylor and Kent (2014).

Additionally, almost every participant said that his or her publics were pleased with the organization’s use of social media for engagement, with only two exceptions (a participant from a museum was unsure about how his organization was using social media in general and a participant from an LGBT advocacy group said that the organization’s presence was still growing so it was hard to say). The participant from the education nonprofit who said that her organization’s crowd funding campaign that reengaged lapsed donors also supports claims made by Botan (1993) because she felt that the publicized dialogue on social media is what brought the former donors back to her organization.

Participants in this study recognized the importance of using social media as part of their organization’s engagement strategy, but the NPOs where they work are often understaffed and underfunded which makes it difficult to invest more heavily in social media. The participants were not weary about the proper usage of social media or the potential for outreach; on the contrary they seemed very comfortable. The most commonly reported concern was that investing time in managing or expanding an NPO’s social media presence meant taking resources away from another area, thus supporting findings made by Obar (2014).

Furthermore, the participants said that they would likely incorporate more social media fundraising campaigns or invest more heavily in online engagement with target

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 34 audiences if their NPOs were able to hire additional employees to manage the online presence, particularly during peak campaign times. A participant who worked at an organization looking to end hunger in Washington, D.C. frequently cited her limited resources and the need to focus on larger sources of funding, like major gifts or grants as the main reason for not being able to invest more time on social media. While she said that she does plan to hire more staff as social media becomes more important for fundraising, she mentioned that this would happen slowly. This finding also supports prior research by Obar (2014).

Nonprofits using social media for fundraising. There were also conflicting opinions among participants regarding the value of using social media for fundraising.

For the most part, participants said that social media should be used to support ongoing fundraising campaigns by raising awareness and engaging with key audiences. Some participants in this study felt that social media is great for fundraising, but that they are still figuring out how to use it effectively. The participant who worked at the feminist and reproductive rights NPO said that even though her organization struggled with figuring out to use social media for fundraising in ways that resonate with their diverse target audiences, they are “diligent” about finding a way to successfully do so.

On the contrary, the participants from the art gallery said that social media does not drive people to give in the way that email does; so while sharing content about an ongoing campaign on social media is helpful, they have not found social media to significantly encourage giving. Similarly, a participant who worked at an LGBT advocacy nonprofit said that he had been able to raise awareness of the organization, which may have resulted in additional donations but he had not yet fully invested in a

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 35 social media fundraising campaign. Moreover, the participant from the environmental protection organization suggested that their website is still what drives gifts, but that social media offers another way to give and may be the first step for a new donor to make an online gift. The fact that none of the participants were able to confidently say that there is a proven method for fundraising on social media is indicative that more research is needed, which was previously noted by Taylor and Kent (2014).

Concerns of “slacktivism” and engagement. The study also supported the research conducted by Paek et al. (2013) who found that online engagement could lead to offline activity, like volunteering. A participant from an LGBT advocacy organization confirmed that his nonprofit had successfully recruited and mobilized volunteers that they initially connected with on Twitter. This demonstrates that social media is a powerful tool for engaging target audiences offline.

The only noted instance of “slacktivism” was the participant from the environmental protection nonprofit who mentioned that engagement on Instagram was

“superficial,” which would support McCafferty’s (2011) criticism of online activism. In fact, the results from this study show that target audiences can be engaged online to the point that they take action about something that they care about. For example, A participant who worked at the art gallery was able to use crowd funding to support a major art exhibit that would have otherwise gone unfunded. The participant from the feminist and reproductive rights organization used crowd funding to purchase a new security system for a partner organization.

Overall, the participants thoroughly understood the advantages and disadvantages of social media platforms. Six participants said that the best platform for engagement

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. truly depended on the type of message and the audience that they wanted to reach.

Several said that Facebook was better for communicating graphics or more detailed information, while Twitter was more public and better for sharing brief updates. This demonstrates that the NPOs were rarely just disseminating information without strategically considering the audience, the message, and the medium, which supports findings made by Briones (2011).

36

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study found that participants who worked for NPOs using social media for dialogic communication were building relationships and raising awareness of the organization, its mission, and any ongoing communications campaigns.

This use of dialogic communication is critical for nonprofits because connecting with target audiences helps them develop deeper ties with their stakeholders and brings them closer to realizing their vision for a better society.

However, in order to achieve their mission, nonprofits depend on support from their donors. Merely engaging in dialogic communication has not yet been proven to be financially rewarding. Participants in this study acknowledged that it is very difficult to equate engagement with dollars raised. One participant noted that they had observed some correlation between social media activity and giving during online campaigns, but ultimately much more research is needed determine if there is such a link.

The study has shown that some nonprofits in Washington, D.C. do not currently see social media as a major tool for soliciting donations; they see it more as an instrument to strategically and dialogically engage publics that can supplement other fundraising efforts.

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 37

There is a significant lack of literature on the subject of using social media for fundraising, which makes it difficult for nonprofits to standardize and streamline their online fundraising strategies. The contrasting opinions among participants in this study about whether or not social media is useful for fundraising indicates a high level of inconsistency among social media practitioners. This represents a significant hole in existing research and demonstrates that that more research is needed to determine how effective, if at all, it is to use social media for fundraising.

Limitations

This study suffered several limitations. A major limitation was reaching out to my personal networks for recruitment, as there is a chance that my relationship with participants may have impacted their desire or ability to give completely honest responses. Additionally, the inconsistency in the size and types of organizations included makes it difficult to compare the social media practices of each organization equally. For example, a major art gallery with a dedicated social media task force is likely to operate differently than a small labor rights advocacy group. It is also probable that these different organizations have different budgets, which can affect how they operate.

Finally, there were technical difficulties when recording interviews conducted over the phone. Some recordings cut out during interviews, which made it impossible to transcribe every interview and may have omitted some information.

Notes for Future Research

The use of social media for fundraising is a new topic that is yet to be fully explored. As this study has shown, nonprofits do not yet have a concrete formula developed to maximize usage of social media for fundraising. One way to obtain more

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 38 information would be to survey similar NPOs to find out how they are using social media for fundraising, what is working, what is not, and why they’ve chosen to conduct social media fundraising. This would help discover what the NPOs hope to obtain in the long term, which could guide future research.

The ideal organizations to participate in this survey would be active on the same social media platforms, have similar number of followers, and operate on similar budgets with similar staff in order to have greater consistency.

Going forward, it would be helpful to know some best practices in order to guide nonprofits to help them successfully execute social media fundraising campaigns.

Presently, based on this study, NPOs are operating based on what they have found to be successful, but additional research may discover patterns and trends that can help them achieve their mission.

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 39

References

Botan, C. (1993). Introduction to the paradigm struggle in public relations. Public

Relations Review , 19 (2), 107.

Briones, R. L., Kuch, B., Liu, B. F., & Jin, Y. (2011). Keeping up with the digital age:

How the American Red Cross uses social media to build relationships. Public

Relations Review , 37 (1), 37-43. doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2010.12.006

Cooks, G., & Sokolic, S. (2009). A case study of a successful donor-nonprofit relationship. Journal Of Jewish Communal Service , 84 (1/2), 132-142.

Foundation Center. (n.d.) About Foundation Center . Retrieved from http://foundationcenter.org/about/

Giving USA Foundation. (2014). Highlights. Giving USA 2014.

Retrieved from http://store.givingusareports.org/Giving-USA-2014-Report-Highlights-P114.aspx

Gordhamer, Soren. (2009). 5 Ways social media is changing our daily lives. Mashable ,

Retrieved from http://mashable.com/2009/10/16/social-media-changing-lives/

Greenberg, J., & MacAulay, M. (2009). NPO 2.0? Exploring the web presence of environmental nonprofit organizations in Canada. Global Media Journal:

Canadian Edition , 2 (1), 63-88.

Hyun Ju, J., & Mira, L. (2013). The Effect of Online Media Platforms on Joining Causes:

The Impression Management Perspective. Journal Of Broadcasting & Electronic

Media, 57(4), 439-455. doi:10.1080/08838151.2013.845824

Ingenhoff, D., & Koelling, A. (2009). The potential of Web sites as a relationship building tool for charitable fundraising NPOs. Public Relations Review , 35 (1), 66-

73. doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2008.09.023

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 40

Kristofferson, K., White, K., & Peloza, J. (2014). The Nature of Slacktivism: How the

Social Observability of an Initial Act of Token Support Affects Subsequent

Prosocial Action. Journal Of Consumer Research , 40 (6), 1149-1166. doi:10.1086/674137

Lee, S. T. (2014). A user approach to dialogic theory in a Facebook campaign on love and marriage. Media, Culture & Society , 36 (4), 437-455. doi:10.1177/0163443714523809

McCafferty, D. (2011). Activism vs. slacktivism. Communications of the ACM , 54 (12),

17-19. doi:10.1145/2043174.2043182

Minnesota Council of Nonprofits . (n.d). Annual Donations and Major Gifts . Retrieved

April 4, 2015, from http://www.minnesotanonprofits.org/nonprofitresources/fundraising-communications/individuals/annual-donations-and-majorgifts

Morozov, E. (2009, May 19). Foreign policy: Brave new world of slacktivism. National

Public Radio. Retrieved April 4, 2015, from http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=104302141

Obar, J. A. (2014). Canadian advocacy 2.0: An analysis of social media adoption and perceived affordances by advocacy groups looking to advance activism in

Canada. Canadian Journal of Communication , 39 (2), 211-233.

Paek, H., Hove, T., Jung, Y., & Cole, R. T. (2013). Engagement across three social media platforms: An exploratory study of a cause-related PR campaign. Public Relations

Review , 39(5), 526-533. doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2013.09.013

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 41

Pew Research Center (2014). Social networking fact sheet .

Pew Research Center .

Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheets/social-networking-factsheet/

Powers, E., & Yaros, R. A. (2013). Cultivating support for nonprofit news organizations: commitment, trust and donating audiences. Journal of Communication

Management , 17 (2), 157-170. doi:10.1108/13632541311318756

Seay, L. (2014, March 12). Does slacktivism work? Washington Post. Retrieved April 4,

2015, from http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/monkeycage/wp/2014/03/12/does-slacktivism-work/

Seltzer, T., & Mitrook, M.A. (2007). The dialogic potential of weblogs in relationship building, Public Relations Review, Volume 33, Issue 2, June 2007, Pages 227-

229, ISSN 0363-8111, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2007.02.011.

Taylor, M., & Kent, M. L. (2014). Dialogic engagement: Clarifying foundational concepts. Journal of Public Relations Research , 26 (5), 384-398. doi:10.1080/1062726X.2014.956106

Kent, M. L., & Taylor, M. (1998). Building dialogic relationships through the World

Wide Web. Public Relations Review , 24 (3), 321.

University of Basel Center for Philanthropy Studies (n.d.) Why Philanthropy?. Retrived from https://ceps.unibas.ch/en/research/why-philanthropy/

Waters, R. D. (2008). Applying relationship management theory to the fundraising process for individual donors. Journal of Communication Management , 12 (1), 73-

87. doi:10.1108/13632540810854244

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 42

Appendices

Appendix 1: Informed Consent Document

Consent to Participate in Research

Identification of Investigators & Purpose of Study

You are being asked to participate in a research study conducted by Andrew Dean. The purpose of this study is to assess how two types of nonprofits (artistic and political) in

Washington, DC are using social media for fundraising. This study will contribute to the student’s completion of his capstone project.

Research Procedures

Should you decide to participate in this research study, you will be asked to sign this consent form once all your questions have been answered to your satisfaction. This study consists of an interview that will be administered to individual participants in various locations, or by phone or Skype. You will be asked to provide answers to a series of questions related to social media and fundraising as it pertains to your organization. The interviews will be audio recorded to facilitate accurate and complete data collection.

Time Required

Participation in this study will require 30-45 minutes/hours of your time.

Risks

The investigator does not perceive more than minimal risks from your involvement in this study.

The investigator perceives the following are possible risks arising from your involvement with this study: there is a chance that the participant may be able to be identified, but this will be minimized by not using the names of participants or of the organizations they work for in any written reports.

Benefits

While there are no direct benefits to the participant, this research is critical to learning how best to leverage the power of social media for fundraising.

Confidentiality

The results of this research will be presented at the end of the semester. The results of this project will be coded in such a way that the respondent’s identity will not be attached to

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 43 the final form of this study. The researcher retains the right to use and publish nonidentifiable data. While individual responses are confidential, aggregate data will be reported on general patterns across the responses as a whole. All data will be stored in a secure location accessible only to the researcher. Upon completion of the study, all information that matches up individual respondents with their answers (including audio recordings) will be destroyed.

Participation & Withdrawal

Your participation is entirely voluntary. You are free to choose not to participate.

Should you choose to participate, you can withdraw at any time without consequences of any kind. You may also refuse to answer any individual question without consequences.

Giving of Consent

I have read this consent form and I understand what is being requested of me as a participant in this study. I freely consent to participate. I have been given satisfactory answers to my questions. The investigator provided me with a copy of this form. I certify that I am at least 18 years of age.

I give consent to be (audio) taped during my interview. ________ (initials)

______________________________________

Name of Participant (Printed)

______________________________________ ______________

Name of Participant (Signed) Date

______________________________________ ______________

Name of Researcher (Signed) Date

If at any point in time you have further questions about this study, you can contact me or my faculty capstone advisor:

Andrew Dean, MA Candidate

Strategic Communication Program

American University

914-424-1875 adean@american.edu

Paula Weissman, Ph.D.

Professorial Lecturer

Public Communication

American University

202-885-6930 paulaw@american.edu

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 44

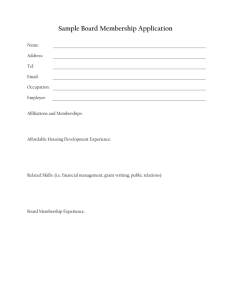

Appendix 2: Background Questionnaire

1.

Name:

__________________________________________________________

2.

Organization Name: _______________________________________

3.

Position Title:

_________________________________________________________

4.

Length of time in position:

______________________________________________

5.

Organization size:

__________________________________________________________

6.

Department size:

_____________________________________________________________

7.

Ongoing major communication objectives (branding, raising awareness, etc.):

_________________________________________

DIGITAL ENGAGEMENT IN D.C. 45

Appendix 3: Interview Schedule

I’m a graduate student at American University, and I’m ultimately looking to see how nonprofits in Washington, DC are using social media to compliment their fundraising efforts. I’m going to ask a few questions about how your organization is using social media as part of a fundraising strategy. If you don’t have any of these answers readily available, please feel free to email them to me after we speak.

1.

Which social media platforms is your organization active on?

2.

Are you able to guess, approximately, how many followers do you have on each platform? Can you estimate to give me a general sense of the size of your followings?

3.

How regularly do you update these platforms? What kind of staff do you have managing the social media presence?

4.

Which platform would you say is best for your engaging your audience? Why?

Can you give me an example of a time when you felt like you really engaged your audience on this platform?

5.

How has the rise of social media shaped your overall engagement strategy, including fundraising? Do you think social media allows direct communication or relationship building with target audiences? Why or Why not?

6.

What types of fundraising campaigns have had any type of a social media presence? (a dedicated hashtag, a crowd funding campaign, an online day of giving, etc.)

7.

How has your organization’s publics reacted to the social media aspect of your fundraising campaign?

8.

What metrics do you have in place to evaluate the performance of campaigns that use social media?

9.

Have your recent social media fundraising campaigns met those metrics?

10.

Which platforms had the best results?

11.

Which platforms had the worst results?

12.

Do you plan on incorporating social media into future fundraising campaigns?