THE REBRANDING OF BLACKWATER: A Directed Research Project

advertisement

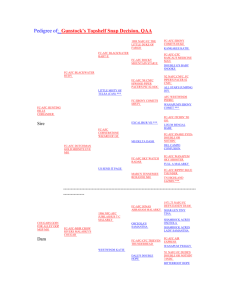

THE REBRANDING OF BLACKWATER: THE EFFECTIVENESS OF A NAME CHANGE AFTER CRISIS A Directed Research Project Submitted to THE FACULTY OF THE PUBLIC COMMUNICATION GRADUATE PROGRAM SCHOOL OF COMMUNICATION AMERICAN UNIVERSITY WASHINGTON, D.C. In Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts By Brittany L. Noble May 2012 Abstract This study explored the effectiveness of multiple name changes as an effective rebranding and reputation management strategy following crisis situations. A content analysis focused on printed articles in The New York Times on Blackwater U.S.A. from the time it was founded in 1997 to 2012 while incorporating attribution theory and situational crisis communication theory (SCCT). Blackwater U.S.A. faced its first crisis in 2004 when four of its employees were ambushed and killed by Iraqi insurgents in Fallujah, Iraq. It faced its second crisis in 2007 when employees were accused of killing or injuring 34 unarmed civilians in Nisour Square in Baghdad, Iraq, without justification or provocation (State Department Public Affairs Office, 2010). The company renamed itself Xe Services in 2009 and Academi in 2011. Blackwater U.S.A. received little coverage in The New York Times after its founding. Coverage increased after the first crisis and the company was covered intermittently until the second crisis. The second crisis sparked the largest increase in coverage in the company’s history, after which it remained steadily in The New York Times. This study found that Blackwater U.S.A. was unable to escape the negative image it received following the second crisis. Every New York Times article studied mentioned Blackwater, despite its name changes. Academi received no coverage and therefore no scrutiny or public criticism. Blackwater and Xe Services continued to be mentioned. Due to not receiving coverage, Academi was able to be more “boring,” a goal it strived for as it looked to survive in a new time in its history (Hodge, Wall Street Journal, 2011). The results support the idea that the first name change was unsuccessful. The second name change was successful and necessary for the company to distinguish itself from the past. 2 Table of contents Introduction....................................................................................................................................4 Study purpose and objective ........................................................................................................4 Study significance ........................................................................................................................4 Rise, fall and change: The history of Blackwater .......................................................................5 Blackwater’s golden years ...........................................................................................................5 Blackwater in the spotlight ..........................................................................................................7 Blackwater’s spotlight: magnified ...............................................................................................7 Government scrutiny ....................................................................................................................8 Rebranding and renaming ............................................................................................................9 Literature review .........................................................................................................................10 Crisis effects on company reputation .........................................................................................10 Situational crisis communication theory and attribution theory ...............................................10 Research questions .....................................................................................................................14 Methodology .................................................................................................................................15 Results ...........................................................................................................................................16 Total print coverage in The New York Times on Blackwater, Xe, or Academi........................16 Tone of print coverage in The New York Times on Blackwater, Xe, or Academi....................17 Primary and secondary mentions of Blackwater, Xe, or Academi ............................................17 Discussion .....................................................................................................................................18 Blackwater’s inescapable past....................................................................................................18 Was renaming an effective rebranding strategy for Blackwater? ..............................................22 Study limitations ........................................................................................................................23 Conclusion ....................................................................................................................................23 Bibliography .................................................................................................................................26 Figures...........................................................................................................................................28 3 Introduction Physics tells us the more mass an object has the more force it takes to change its direction. This idea can also be applied to brands (Cobley, 2010). The more massive a brand is the more force it needs to change its position. This is compounded for companies facing crisis communications situations. This project will focus on the crisis communication situations that Blackwater U.S.A.1 faced following incidents that involved its employees in Iraq and its strategy to rebrand itself: changing its name twice. Study purpose and objective This study explores the effectiveness of multiple name changes as an effective rebranding and reputation management strategy following crisis situations. A content analysis will focus on printed articles in The New York Times that follow Blackwater from its inception through two name changes until January 2012. It will measure how the private contracting company was portrayed in The New York Times before, during, and after its two largest crisis situations; one in which four employees were reportedly attacked and killed by Iraqi insurgents and one in which employees reportedly opened fire in a marketplace, killing 17 Iraqi civilians. By incorporating attribution theory and situational crisis communication theory (SCCT) this study will explore the use of multiple name changes as an effective rebranding and reputation management strategy. The paper will ultimately determine if renaming was an effective strategy for Blackwater and Xe Services following crisis communications situations portrayed in The New York Times. Study significance 1 For consistency and simplicity, the company will primarily be referred to as Blackwater. 4 This study may be significant for any organization facing a crisis situation, particularly companies or leaders in the defense industry, trying to determine if renaming is an effective rebranding strategy following the crisis. It may also be used in works that study other prevalent name changes following crisis situations such as Andersen Consulting to Accenture, Phillip Morris to Altria, and ValuJet Airlines to Airtran Airways. The study may also be used to explore the levels of transparency the government owes the public and the importance of government and government-hired institutions having a media strategy. Rise, fall and change: The history of Blackwater Blackwater’s golden years In 1997, former U.S. Navy Seal Erik Prince founded Blackwater, a private contracting company. Prince stated in his 2007 testimony before Congress that the company was “The most comprehensive professional military, law enforcement, security, peacekeeping and stability operations company in the world” with a mission “To support security, peace, freedom, and democracy everywhere” (CSPAN, 2007). Blackwater was a privately-held company headquartered in Moyock, N.C., where the 5,200 acre training facility was located (Chinni, 2002). Gary Jackson served as the Chief Operating Officer and Prince as President. Jackson attributed September 11, 2001, to the increase in business, training and contracts. At the time, “the largest private firearms training facility” attributed 70 percent of its business to the U.S. military, including the Navy Atlantic Fleet, and security assignments to Olympic Games (Chinni, 2002). Still, the company opened training to anyone who could afford the $895 weekly fee (Chinni, 2002). 5 In his book, “Blackwater: The Rise of the World’s Most Powerful Mercenary Army,” Jeremy Scahill stated, “Blackwater was viewed as an elite security company because of its highprofile contract guarding the top U.S. officials and several regional occupation headquarters. But while Blackwater encouraged this view, both in Baghdad and Washington, of a highly professional all-American company patriotically supporting its nation at war, it quietly began bringing in mercenaries from shady quarters to staff its ever-growing security contracts in Iraq” (246). In August 2003, Blackwater was awarded a $27.7 million contract to provide private security detail in Iraq and due to its increasing contracts raised its fee for the service from $300 to $600 daily (Scahill, 134). The New York Times did not publish a single story on Blackwater from the time of its founding in 1997 until April 28, 2002. The first article to mention Blackwater, “The Way We Live Now,” painted a visual picture of the Blackwater Training Facility in Moyock, N.C., by describing a Blackwater-released brochure. It states: “The brochure for Blackwater Training Center is not subtle. The cover shows three men in camo with guns drawn, and on the back a man in sunglasses -- Meet Gary Jackson, Chief Operating Officer -- aims his rifle directly at the reader” The informational article seemed to portray Blackwater as the company would have portrayed itself. They were a company that eased environmental concerns by providing an 6 isolated facility for target practice, they provided realistic skill-training in simulated environments, and were an asset to the industry of elite military training in the wake of September 11, 2001. On October 11, 2002, Blackwater was referenced again in The New York Times. This time, the company was cited as an expert in responsible use of ammunition in “The Maryland Shootings: Gun Owners; Subculture of Snipers Disowns a Marksman.” Blackwater instructor Norm Chandler discussed the lack of formal training in the sniper subculture and said he “discourages such people” from attending his courses at Blackwater, berating them as “idiots” (Butterfield, 2002). Blackwater in the spotlight On March 31, 2004, two years into America’s war with Iraq, four State Department-hired private contractors with Blackwater were ambushed and killed by Iraqi insurgents in Fallujah, Iraq. The New York Times reported that a riot ensued on the streets of Fallujah following the deaths and the bodies were publicly burned, beaten, mutilated and hung from a bridge (Tavernise and Napolitino, 2004). This incident brought private military contracting to the forefront of an already controversial war and was the first publicly-reported crisis the company faced. Blackwater was thrust into the spotlight and the public began to pay attention to “private security contractors” in Iraq. Prior to the incident, The New York Times had only reported on Blackwater twice. The coverage grew substantially between April and June 2004 and Blackwater appeared in 15 New York Times articles – more than five times the amount it had appeared in the seven years of its existence. Blackwater’s spotlight magnified 7 Blackwater faced its second crisis situation on September 16, 2007, when members were accused of killing or injuring 34 unarmed civilians in Nisour Square in Baghdad, Iraq, without justification or provocation. (State Department Public Affairs Office, 2010). Now, the largest State Department contractor was not just in the spotlight, it was facing a crisis situation that not only affected its organization, but the U.S. on political and public diplomatic levels. Government scrutiny Representatives from Blackwater were first required to testify before Congress in October 2007 at a hearing entitled “Blackwater and Private Security Firms in Iraq.” Representative Henry Waxman, a Democrat from California, opened the meeting stating, “Over the past 25 years, a sophisticated campaign has been waged to privatize government services.” He stated that privatization had exploded. Waxman specifically referenced Blackwater as a company that has made large financial gains acting in roles that had previously been considered as inherently military. He raised the question: “Is Blackwater, a private military contractor, helping or hurting our efforts in Iraq?” (Blackwater and Private Security Firms in Iraq, 2007). Throughout the hearing, the company was scrutinized for not being held accountable for actions that resulted in deaths of civilians and for which a member of the military would have received a court martial for (Blackwater and Private Security Firms in Iraq, 2007). Congress was unable to ask about the September 16, 2007, shooting due to an ongoing FBI investigation. Prince was present at the hearing and testified. In 2008 Congress created the bi-partisan Commission on Wartime Contracting (CWC) to explore if $60 billion had been lost in U.S. contingency operations in Iraq and Afghanistan due to contract waste, fraud and abuse (Transforming Wartime Contracting: Controlling Costs, 8 Reducing Risks, 68). In its final report to Congress, the CWC used Blackwater as a “prime example” of the risk the U.S. faces on foreign soil, particularly the “public-opinion backlash in the local communities and governments … after contractors are accused of crimes” (30). The report also acknowledged the “sensitivity” of private contractors performing certain services, specifically mentioning Blackwater in half of its examples (40). While Blackwater was provided as a prime example, the report showed they were one of the smaller contingency contractors in the industry. In fiscal years 2002-2011, KBR, the top vendor, received $40.8 billion in contracts while Blackwater received $1.4 billion, far less in comparison (Transforming Wartime Contracting: Controlling Costs, Reducing Risks, 26). Rebranding and renaming On February 13, 2009, Blackwater was renamed to Xe Services. An article about the name change referenced an internal memo from President Gary Jackson that the move reflected the company’s focus shifting from private security to training (The New York Times, 2009). An overview of the company stated that public scrutiny on Blackwater during the U.S.-led contingencies in Iraq and Afghanistan “forced an image re-do” (McClellan, 2012). It remained a privately-held company. On March 2, 2009, Erik Prince resigned from the company and as the chief executive officer and Joseph Yorio became president and Danielle Esposito became chief operating officer (Reuters, 2009). On June 1, 2011, Xe Services announced Ted Wright as its new chief executive officer (CNN, 2011). Wright said he would, “help Xe navigate its next phase of development and growth” (CNN, 2011). 9 On December 12, 2011, Xe Services announced it was changing its name to Academi. Academi was acquired for $200 million. It is listed as having 1,000 employees with the leadership team consisting of Billy McCombs, chairperson, Ted Wright, chief executive officer, and Charles Thomas, chief operating officer (McClellan, 2012). It lists annual sales of $350 Million. As of April 2012, Academi was a privately-held company. Wright said that the move to Academi was “more than a simple name change” and a reflection of changing the things that need to be changed “while retaining those elements that made us who we are–the best in our industry” (Academi Press Release, 2011). The company narrowed its focus by taking a “scholarly approach to military contracting … become primarily a provider of military and technical training services for counterterrorism operations, force protection, law enforcement agencies, and other private security operations” (McClellan, 2012). Literature Review Crisis effects on company reputation In a crisis, organizations must successfully manage their reputation. While they will undoubtedly face losing consumer support and profits as well as their overall credibility, effectively communicating with the media, stakeholders and employees early and often will reduce these losses. To successfully manage reputation, a company facing a crisis must first identify and prioritize its target audiences. Depending on the nature and severity of the crisis, all stakeholders may be affected. In the case of government service, whether it is direct or contracted, there must be a level of accountability to the public. Situational crisis communication theory and attribution theory 10 To determine the best strategy, the crisis must be classified. Coombs and Holladay (1996) identified four types of crises: accidents, transgressions, faux pas and terrorism. Accidents are unintentional and internal, transgressions are intentional and internal, faux pas are unintentional and external, and terrorism is intentional and external (284). The categorization is illustrated in Figure 1. Coombs and Holladay then identified the best strategies to align with the characteristics of the crisis type. When addressing organizational image, Coombs and Holladay offer five groups of strategies: denial, distance, integration, mortification and suffering. Using a matrix, the hypothetical responses, or strategies, could be placed with crisis types. For example, for a faux pas, ambiguity provides an opportunity to convince stakeholders there is no crisis and the denial strategy is most effective. Transgressions are best fixed by repairing legitimacy through media strategies to adhere to stakeholders’ expectations. Accidents and terrorism must emphasize the unintentional by reducing responsibility of the organization. Distance strategies work best in this instance, such as excuses or justification. Situational crisis communication theory (SCCT) measures level of reputational threat to a company in crisis situations. Coombs states that “a crisis response can reduce or eliminate [reputational] threat” (2007). A company’s response to the media can reduce or eliminate reputational threat. Blackwater faced two crises – one that placed it in the spotlight and not at fault for a controversy and another that placed it at fault for a controversy. Because Blackwater’s was a crisis on many levels: organizationally, politically and diplomatically, there were many complexities surrounding the situation that affected how it could respond to the public and the media. 11 The first crisis Blackwater faced was framed in The New York Times as terrorism, or an intentional action taken by an externally controlled factor. In this case, Iraqi insurgents committed an act against Blackwater employees and the company was not held at fault for the incident although it did place Blackwater in the spotlight. Strategies for dealing with this type of crisis include reducing responsibility of the organization and using distance strategies such as excuses or justification. Blackwater’s second crisis was framed in The New York Times as a transgression, or an intentional action taken by those internal to the company. Transgressions are best fixed by repairing legitimacy through media strategies to adhere to stakeholders’ expectations. It could be assumed that Blackwater would benefit from making this crisis appear as unstable and not fitting with its prior reputation. The first logical step Blackwater should have taken was speaking regularly with the media and responding to requests for information. Attribution theory can also be used by professionals in dealing with a crisis. Attribution theory explains “why a particular event, or state, or outcome has come about and the consequences of phenomenal causality” (Weiner, 2000). The broadness of this theory makes it easily applied to many fields. It has been applied to research in consumer marketing, psychology and crisis communication. Weiner studied attribution theory in relation to consumer purchasing and his findings can also be used when looking at how target audiences in crisis situations shape their views of an organization or company. The likelihood of success, or satisfaction, is something that consumers attribute, or do not attribute, to products based on past outcomes (negative or positive experiences). Sometimes these are stable or enduring, but at other times these are temporary and inconsistent. 12 Weiner states that repeated failures will eventually result in a consumer’s attribution reevaluation even if something was at one time considered to have stable positive outcomes. Consumers are more likely to attribute a negative outcome as inconsistent, or random, if they feel that a product is generally stable and has positive outcomes. Conversely, consumers are more likely to attribute a positive outcome as unstable if a product is generally unstable and has negative outcomes. In a crisis situation, this idea could also come into play. If a company is thought to have a consistent negative reputation, the public may be less forgiving if something positive happens as they will attribute that positive outcome to something instable. This is because, “satisfaction following a series of unsatisfying experience is unlikely” (Weiner, 384). The media has the ability to shape public opinion and compound the effects of attribution theory. For example, if a company is repeatedly portrayed negatively, in a stable manner, the consumer may begin to associate the company with negative events or attributions. The process that consumers go through starts with thinking, where attributions and stability of outcomes are established, moves to feeling and finally to taking an action. For target audiences of companies in crisis situations, it is important that the crisis is seen as unstable and not fitting what the company stands for. If a company fails at creating this image, the crisis will be attributed as a stable action that is in line with how the company is, further shaping its reputation as a negative one. Weiner states this would ultimately lead to “consumer avoidance.” In the case of crisis situations, this “avoidance” is equivalent to being written off completely by stakeholders and target audiences, leaving the company no chance of recovery. This is why it is particularly important in the case of transgressions that companies cooperate with the media and create relationships to repair its image. Companies must be responsible for managing their impressions, 13 a task that becomes increasingly complex when dealing with the media and in today’s social media, where every individual has a publicly-heard voice. Weiner said strategies for dealing with crisis situations are denial, excuses and confessions, a slightly less comprehensive list than Coombs and Holladay produced. For the purpose of this project, Weiner’s strategies have been condensed into the categories created by Coombs and Holladay. Denial will be placed in the category of denial, excuses in the category of distance, and confessions in the category of integration. All strategies ultimately portray that whatever happened was a one-time occurrence and therefore unstable. All are strategies that maintain relations. While confession admits guilt, it “gives rise to the inference that a good person committed a bad act … lowers the moral condemnation against the transgressor, but also reduces beliefs that the act will be committed again” (Weiner, 386). This is critical to ensure companies remain in the public’s good graces. Any company facing a crisis situation is likely facing an internal and external crisis and must carefully consider how all stakeholders, including employees, must be reached and communicated with. Blackwater’s situation was much larger than that due to the nature of it being a private company contracted to a government organization (U.S. Department of State) that was stationed overseas (Iraq) conducting a mission. Research questions This study will answer the following research questions: 1. Was renaming an effective crisis strategy for Blackwater following crisis communications situations, based on how it was portrayed in The New York Times? 14 2. How much print coverage was there in The New York Times on Blackwater, Xe or Academi between 1997 and 2012? 3. Was print coverage in The New York Times mentioning Blackwater, Xe or Academi between 1997 and 2012 negative, positive or neutral? 4. What is the comparison between primary and secondary mentions of the company? Methodology Content analysis is a prominent way to study media coverage (Bolsen, 144). A census was drawn of all articles in The New York Times from January 1, 1997, to January 31, 2012, that contained any combination of the terms Blackwater, Xe or Academi. A total of 462 articles were found. All articles that contained the terms but were not in relation to the company were removed. For example, articles that addressed the Blackwater River or a musical group by the same name were excluded. Anything not considered to be written by a journalist, such as an opinion editorial (OpEd), book review or letter to the editor was removed. To ensure only print articles were analyzed, blog posts, corrections and news summaries were also removed. This left 245 articles for analysis. The articles were divided into two time periods to ensure both crises were taken into account. It also ensured there were enough articles in time period one to make a valid comparison with time two. Time period one contained articles written between the company’s founding (1997) to the end of the quarter before the second crisis (June 30, 2007) for a total of 38 articles. Time period two contained articles written from the beginning of the quarter containing the second crisis (July 1, 2007) to the end of the data collection (January 31, 2012) for a total of 15 207 articles. Every third article in time period one was coded for a total of 13 articles. Every sixth article in time period two was coded for a total of 35 articles. Stories were coded for primary or secondary mentions and tone. Primary mentions were stories that used the company as its main topic (for example, it was in the headline, or a situation took place that directly involved the company), such as articles speaking directly about either crisis situation or articles covering the congressional hearings. Secondary mentions were ones that did not use the company as its main topic, such as an article stating Iraqis are upset at Americans, and subsequently mentioning the company. Tone was coded as negative, positive or neutral. Negative articles contained more critical information than supportive information, making them unbalanced. They associated the company with bad things using dramatic language, phrases and quotes such as “troubling trend,” “creating a monster” (Gettleman, Mazzetti and Schmitt, 2011) and “mounting problems” (Mazzetti and Hager, 2011) without balancing it out with the opposite perspective. Unbalanced articles may also be produced if the reporter attempted to contact the company and it declined to provide a statement to the media. Articles containing positive tones were also unbalanced, containing facts that leaned toward associating a situation or the company with good things using dramatic language, phrases and quotes such as “indicating they are lacking honor … that’s ridiculous” (Dao, 2004) or referring to the company as “world class” (Dao, Schmitt and Burns, 2004) without balancing it out with the opposite perspective. Neutral articles were well-balanced; they contrasted facts from both critics and supporters of the company. Reliability was tested by providing a sample of five randomly sampled articles and a coding sheet to an additional coder resulting in 100 percent reliability. 16 Results Total print coverage in The New York Times on Blackwater, Xe or Academi Blackwater was covered intermittently following the first crisis in 2004 until its second crisis in 2007 where it received more coverage in a three-month period than it had in the past five years. It continued to receive coverage regularly following the second crisis. Figure 2 shows there were 245 articles in The New York Times on Blackwater, Xe or Academi during the time we studied. All of the articles contained mentions of Blackwater and none mentioned Academi. Over the 15-year time period, the largest concentration of articles was between October 2007 and December 2007 where there were 50 articles. The next largest concentration of articles was 21 between January and March 2010. The third largest concentration of articles was between July and September 2007 with 18 articles. Tone of print coverage in The New York Times on Blackwater, Xe or Academi The majority of print coverage in The New York Times mentioning Blackwater, Xe or Academi between 1997 and 2012 was neutral. The number of negative articles increased in the second time period in comparison with the first. The sample of articles from time period one contained 62 percent neutral articles, 31 percent negative articles and 8 percent positive articles. The sample of articles from time period two contained 46 percent neutral articles, 43 percent negative articles and 11 percent positive articles. The negative and neutral articles were much more proportionate in time period two than time period one. In time period two, neutral articles decreased by 16 percent and negative articles increased by 16 percent. Figure 3 shows the results of the tone of print coverage in The New York Times on Blackwater, Xe or Academi for time periods one and two. 17 Primary and secondary mentions of Blackwater, Xe or Academi Eighty-five percent of articles in time period one contained secondary mentions of Blackwater or Xe and 15 percent were primary mentions. In time period two, the numbers changed dramatically with only 42 percent being secondary and 57 percent being primary. There was a 16 percent increase in primary negative articles from time period one to time period two. There was a 17 percent increase in primary neutral articles. The company was mentioned significantly more in secondary neutral articles in time period one (53.85 percent) than it was in time period two (23.08 percent). In time period two, secondary mentions in both negative and neutral articles were equal at 20 percent. Discussion Blackwater’s inescapable past Blackwater was unable to escape its negative past after its initial renaming to Xe Services years after both crises took place. Of 245 articles in The New York Times, all mentioned Blackwater and none mentioned Academi. Following its 2009 name change, Blackwater continued to be referenced in the media, sometimes without mentioning the new company name at all. The largest concentration of coverage was between October 2007 and December 2007 where it received more coverage in three months than it had in the five years prior. It steadily remained in the media following its second crisis. The majority of print coverage in The New York Times mentioning Blackwater, Xe or Academi was neutral. Yet the increase of negative articles in the second time period supports the idea that the media covered crisis situations where a company was at fault more often and longer. The number of neutral articles decreased in time period one by the same amount the negative 18 articles increased in time period two (16 percent) supports the idea that neutral coverage was replaced by negative coverage. Blackwater’s primary mentions in The New York Times increased significantly following its second crisis. This not only supports the idea that the media was more likely to cover a crisis situation when a company was at fault steadily and for a greater length of time, but more primarily. This also supports the idea that Blackwater was unable to escape the negativity of its past or publicly shake the things it had done. The secondary mentions were important to analyze as well. Following the first crisis, which Blackwater was not blamed for, there were far more secondary mentions in neutral articles than negative ones. Following the 2007 crisis, Blackwater’s transgression became somewhat common knowledge, often being cited in articles that had nothing to do with the 2007 Nisour Square incident. Such articles were about a negative event that had occurred involving a different company or the Iraq conflict. They also became known in popular culture, sometimes mentioned in articles about video games or television shows (Itzkoff, 2008). After the second crisis, the secondary mentions in neutral and negative articles were equal. The secondary mentions in negative articles support the idea that Blackwater was associated with negative events that took place that had little to do with them directly. Attribution theory states that if a company is repeatedly perceived as negative, the consumer will begin to associate the company negatively, even if something goes right later on. The first crisis Blackwater faced was framed in The New York Times as terrorism, or an intentional action taken by an externally controlled factor. The best strategies for dealing with a crisis categorized as terrorism are to emphasize the unintentional by reducing responsibility of 19 the organization (Coombs and Holladay, 284), which Blackwater did successfully following its first crisis situation. This is evident in the media coverage having significantly more neutral than negative articles in time period one and there being more secondary mentions than primary ones. The tone of the coverage combined with the mentions show Blackwater successfully emphasized that the crisis was an action taken against it therefore reducing its responsibility of any wrongdoing. Strategies that help implement this are excuses and justification, both of which were displayed in New York Times coverage, such as when Chief Operating Officer Gary Jackson was quoted saying, “'We lost a number of our friends to attacks by terrorists in Iraq and our thoughts and prayers go out to their family members” (Opel and Worth, 2005). The second crisis Blackwater faced was framed in The New York Times as a transgression or an intentional action taken by an internally controlled factor. Transgressions are best fixed by repairing legitimacy through media strategies to adhere to stakeholders’ expectations and reduce the responsibility of the organization (Coombs and Holladay, 284). It could be assumed that Blackwater would benefit from making this crisis appear as unstable and not fitting with its prior reputation, however, it failed to do this. The first logical step Blackwater should have taken was speaking regularly with the media and responding to requests for information. The number of negatively unbalanced articles in time period two was high and this can be attributed to, at least partially, the fact that Blackwater did not provide statements to the media or actively engage with them. It appears that The New York Times was less likely to report on the incident in which Blackwater was not at fault than the one in which they were. Unbalanced articles could be attributed to two possible causes; they were either unfair to the company, such as mentioning them in a story where a negative event happened that did not involve the company, or the 20 company declined to comment, leaving them to be scrutinized rather than choosing to defend themselves. Stories that are more personal or negative have a higher chance of being covered by the media (Donsbach, 2004) and this can explain why stories following Blackwater’s crises increased. They involved the deaths of U.S. citizens and the deaths of Iraqi civilians; both were overall negative subjects and contained a higher chance of being personalized due to the fact they involved humans. The New York Times personalized many of the stories, quoting family members and eyewitnesses. This attributed too much of the dramatic language in the articles. Blackwater and the State Department at times did not comment on situations being reported on in the media. This may have led to more negative articles because reporters were only able to receive interviews from Iraqi citizens, family members who felt wronged, or eyewitnesses of the traumatic events that took place. Many government-affiliated organizations may be operating under strict constraints of what they can and cannot say to the public at different times. These constraints may be legal, political or security-related. These constraints likely applied to Blackwater following their second crisis situation and limited what they could say to the media and the public. This may have prevented Blackwater from taking desired public action when it desired to do so. Attribution theory explains a company’s public image can be shaped and the media compounded a negative public image for Blackwater. The process that consumers go through starts with thinking, where attributions and stability of outcomes are established, moves to feeling and finally to taking an action. For target audiences of companies in crisis situations, it is important that the crisis is seen as unstable and not fitting what the company stands for. If a 21 company fails at creating this image, the crisis will be attributed as a stable action that is in line with how the company is, further shaping its reputation as a negative one. Weiner states this would ultimately lead to “consumer avoidance.” In the case of crisis situations, this “avoidance” is equivalent to being written off completely by stakeholders and target audiences, leaving the company no chance of recovery. This is why it is particularly important in the case of transgressions that companies cooperate with the media and create relationships to repair its image. Companies must be responsible for managing their impressions, a task that becomes increasingly complex when dealing with the media. When a company is unable to speak on a matter publicly due to legal, political, or security-related constraints, it is problematic. Was renaming an effective rebranding strategy for Blackwater? Blackwater’s first name change to Xe Services was unsuccessful. This is supported by the data found when we analyzed Blackwater’s crisis situations and The New York Times coverage of the events. Due to the increase in coverage of Blackwater, the company was unable to escape its negative image in the public eye. Partially due to the ineffective way Blackwater dealt with the second crisis, the first name change did not successfully distance the new company from the situation. Blackwater was constantly referenced in articles mentioning the crisis situations and Xe Services was mentioned as an afterthought. Ted Wright, president and chief operating officer of Xe Services, acknowledged the first name change was unsuccessful in 2011. He stated, “Do I think the rebranding of Xe was successful? Absolutely not … Here's the reason why: All they did was change the name of the company; they didn’t change the company” (Hodge, Wall Street Journal, 2011). 22 The second name change from Xe Services to Academi, while unlikely, was a necessary and effective rebranding strategy for the company. This is supported by the data found when The New York Times coverage was analyzed. Academi was not mentioned at all. If the company’s intent was to distance itself from the incidents, a second name change appeared to be their best option. As world events change, renaming may be a very effective strategy providing a company a change to “recover” and continue to distance themselves from a crisis. Academi twice-removed itself from the crisis. Study limitations Limitations in this study are that only one publication was used. This topic may have been heavily covered in trade publications such as military- or defense-related publications. It may have also been heavily covered in publications local to where Blackwater was located or towns with a strong military presence. It is also important to note that the second name change to Academi occurred in December 2011 and the content analysis ended on January 31, 2012, less than two months later. While there was no coverage on Academi in The New York Times until that date, it is possible the new name was covered after that date. Conclusion The larger a company is, the more that will be needed to change it. The larger a crisis is, the more drastic an effort must be to correct it. As Blackwater was increasingly covered in media and received scrutiny from the public and government alike, changing its name had the potential to be extremely hazardous. They risked appearing as though they were just trying to cover up their actions, losing credibility, and not being viewed by the public as changed at all. 23 The media plays a significant role in shaping public perspective of companies and situations and has the potential to change how a company is viewed forever. In today’s fastpaced information age, the public has more control than ever. Because information can be distributed – and varying opinions can be provided quickly – it is critical that companies take control of a crisis situation and take action from a communications perspective. If they do not do this, they risk losing everything. Blackwater received little coverage in The New York Times prior to its crisis situations being only mentioned twice. The study found an initial increase in coverage mentioning Blackwater after the original crisis situation, categorized as terrorism, in which four State Department-hired private contractors with Blackwater were ambushed and killed by Iraqi insurgents in Fallujah, Iraq in 2004. It was covered intermittently until 2007 when Blackwater members were accused of killing or injuring 34 unarmed civilians in Nisour Square in Baghdad, Iraq, without justification or provocation. (State Department Public Affairs Office, 2010). The study found that following the second crisis situation, Blackwater was unable to escape the negative image it received, even after subsequently changing its name to Xe Services in 2009. Every single article studied mentioned Blackwater despite its name change. In 2011, Xe Services was renamed to Academi, which received no coverage in The New York Times while Blackwater and Xe Services continued to be mentioned. This suggests the first name change was unsuccessful and the second name change was successful. When The New York Times initially reported on the name change, it continued to primarily reference Blackwater and discuss Xe as an afterthought, forever linking the new name an old scenario. A second change, while an unlikely choice was actually a necessary and effective maneuver to save the company’s reputation. In fact, this analysis shows it was almost 24 inevitable that they do something drastic to distinguish themselves as changed and remove the shadows of the past. As Academi, the company received less media coverage, and therefore, scrutiny and public perception. It was ultimately able to be more “boring,” which is exactly the goal the company was trying to reach (Hodge, Wall Street Journal, 2011) as it turned a new leaf and looks to survive in a new time in history. The only true test to tell how effective renaming was for Academi is time. This study proves that it in the immediate aftermath, a third name change was an effective and smart strategy for a company that once appeared destined to be haunted by a destructive past. 25 Bibliography Academi Press Release. (2011). Leading Training and Security Services Provider Xe Services Announces Name Change to ACADEMI, New name draws on company legacy while building on new leadership, governance and strategy: Academi. Associated Press. (2009). Blackwater Changes Its Name to Xe, The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2009/02/14/us/14blackwater.html?_r=1 Blackwater and Private Security Firms in Iraq. (2007), Oversight and Government Reform Committee: CSPAN. Bolsen, T. (2010). The Construction of News: Energy Crises, Advocacy Messages, and Frames toward Conservation. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 16(2), 143-162. doi: 10.1177/1940161210392782 Butterfield, F. (2002). THE MARYLAND SHOOTINGS: GUN OWNERS; Subculture of Snipers Disowns a Marksman. The New York Times. CNN. (2011). Xe, formerly Blackwater, announces new chief. CNN. Retrieved from http://articles.cnn.com/keyword/halliburton Cobley, Dan. TEDglobal video http://www.ted.com/talks/dan_cobley_what_physics_taught_me_about_marketing.html Coombs, T. W. (2007). Attribution Theory as a guide for post-crisis communication research. Public Relations Review, Vol. 33(2), 135-139. Coombs, T. W., and Holladay, S. J. (1996). Communication and Attributions in a Crisis: An Experimental Study in Crisis Communication. Journal of Public Relations Research, 8(4), 279-295. Commission on Wartime Contracting in Iraq and Afghanistan. (2011). Transforming Wartime Contracting: Controlling Costs, Reducing Risks (pp. 248). Arlington, Va. Dao, J. (2004). 'Outsourced' or 'Mercenary,' He's No Soldier. The New York Times. Dao, J., Schmitt, E., Burns, J. (2004). Private Guards Take Big Risks, For Right Price. The New York Times. 26 Department of State, Office of the Assistant Secretary, Bureau of Public Affairs (2010). Federal District Court Dismissal of Indictment Against Blackwater Contractors [Press release]. Retrieved from http://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2010/01/134971.htm Donsbach, W. (2004). Psychology of News Decisions: Factors behind Journalists’ Professional Behavior. Journalism, 5(2), 131-157. doi: 10.1177/146488490452002 Gettleman, J., Mazzetti, M., Schmitt, E. (2011). U.S. Relies on Contractors in Somalia Conflict. The New York Times. Hodge, Nathan. (2011). Contractor Tries to Shed Blackwater Past, Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052970203405504576599123967308168.html Itzkoff, Dave. (June 22, 2008). The Shootout Over Hidden Meanings in a Video Game. The New York Times. Mazzetti, M., Hager, E. (2011). Secret Desert Force Set Up By Blackwater's Founder. The New York Times. McClellan, Michael. (2012). Academi LLC. http://subscriber.hoovers.com.proxyau.wrlc.org/H/company360/overview.html?companyI d=158907000000000 Oppel, R. A. and Worth, R. F. (April 22, 2005). A Private Copter Crashes in Iraq; 6 Americans Die, The New York Times. Reuters. (March 2, 2009). Blackwater founder resigns as chief executive, Reuters. Retrieved from http://www.reuters.com/article/2009/03/02/us-xe-ceoidUSTRE52162Q20090302?feedType=RSS&feedName=domesticNews Scahill, Jeremy. (2007). Blackwater: The Rise of the World's Most Powerful Mercenary Army: Nation Books. Tavernise, S. and Napolitano J. (2004). Grief, Mostly in Private, for 4 Lives Brutally Ended. The New York Times. Weiner, B. (2000). Attributional Thoughts About Consumer Behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 27, 382-387. 27 Figures Figure 1. Crisis classification to determine the appropriate strategy (Coombs and Holladay, 1996) Externally controlled crisis Internally controlled crisis Intentional action Terrorism Transgression Unintentional action Faux Pas Accident Figure 2. New York Times print articles mentioning Blackwater, Xe Services or Academi between January 1, 1997, and January 31, 2012, by quarter. 28 Figure 3. Results of negative, positive and neutral tone articles in The New York Times for time periods one and two (n=48). Positive Neutral Negative Time period 1 (n=13) 8% 62% 31% Time period 2 (n=35) 11% 46% 43% Figure 4. Primary and secondary mentions in positive, negative or neutral tone articles sampled for time periods one and two (n=48) Time period 1 (n=13) Time period 2 (n=35) Primary/positive 0 8.57% Primary/neutral 7.69% 25.71% Primary/negative 7.69% 22.86% Secondary/positive 7.69% 2.86% Secondary/neutral 53.85% 20% Secondary/negative 23.08% 20% 29