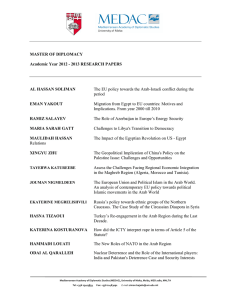

Mediterranean Academy of Diplomatic Studies (MEDAC)

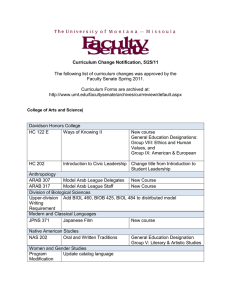

advertisement