Document 13237773

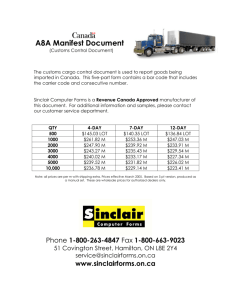

advertisement