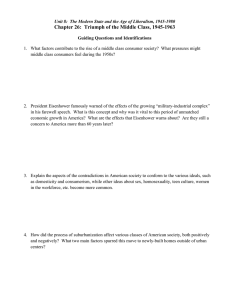

What Congress Looked Like From Inside the Eisenhower White House

advertisement

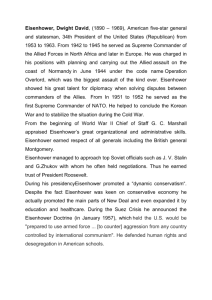

What Congress Looked Like From Inside the Eisenhower White House By Stephen Hess As a parting gift to each of us who served on President Eisenhower‘s staff, our colleagues Fred Fox and Jim Lambie compiled White House…Staff Book…1953-61. It was something like a high school yearbook, with photos and bios of the graduates.1 After nearly a half century, it‘s a useful place to start memory-jogging on who was there and how Congress looked to us. It‘s also a way to keep in perspective the differences in White House staffs, then and now. First, there‘s the matter of size. Ours was tiny. On most days we could all have lunch at the same time in one small oblong room in the West Wing basement. In compiling their staff list, Fox and Lambie didn‘t give us the key to who was in and who was out, but my hunch is that they included only those with White House Staff Mess privileges. I will return to the Mess and its importance later; still, I think they chose realistically, even though this produced a couple of anomalies, such as including Milton Eisenhower, Ike‘s brother and President of Johns Hopkins, of whom they wrote, ―He gave his service to the President on various occasions at home and abroad and was a familiar figure around the White House.‖ Also Robert Montgomery, the actor-director: ―During the 1952 campaign, he became a television consultant to the President, and since then he has come down [from New York] to the White House whenever needed.‖ One hundred-three names made the A-List for serving at some point during Eisenhower‘s two terms. Exclude 15 military aides, such as the Air Force One pilots and 2 the President‘s doctors, and this left just 88.2 The group included 6 college presidents, 6 who had been generals, 5 former governors, but only 3 who had been elected to Congress.3 The burgeoning of White House staffs over time reflects two trends. One: Adding people to perform added functions. When I returned to the White House in 1969, for instance, I worked for a unit, the Urban Affairs Council, that hadn‘t existed when I left the White House in 1961. Two: A more rapid turnover rate among staffers.4 Had overheated White House operations produced more burnout, a different sort of person, or the lure of more opportunities outside of government? Of the 88 at Eisenhower‘s White House, a dozen stayed for the full eight years, among them a core of such prominent aides as James Hagerty (press secretary), Bryce Harlow (speechwriting, legislative relations), Gerald Morgan (legislative relations, counsel), Wilton Persons (legislative relations, chief of staff), and Thomas Stephens (appointment secretary). Another dozen stayed almost as long. The demographics reflect major differences from recent staffs. The 88 were almost all male, all white: There were three women and one African-American.5 Staffs now are also much younger. Between 1953 and January 1961 there were only five assistants in their twenties. I was the youngest at 25.6 Eleven were in their thirties, including Bradley Patterson, 33, who would become the leading authority on White House organization.7 I arrived at the White House shortly after Labor Day, 1958--having just been mustered out the army as a private first class--to assist my Johns Hopkins mentor, Malcolm Moos, recently named the President‘s speechwriter.8 My White House 3 impressions cover only the last two-plus years of the administration. However, I did serve with 58 of the 88, again a reflection of Ike staffers‘ long tenure. [space] Dwight Eisenhower had strong feelings about staffs and how they were expected to work. In the first volume of his presidential memoirs, he wrote, ―For years I had been in frequent contact with the Executive Office of the White House and I had certain ideas about the system, or lack of system, under which it operated.‖ He would ―organize the White House for efficiency….Organization cannot make a genius out of an incompetent….On the other hand, disorganization can scarcely fail to result in inefficiency and can easily lead to disaster.‖9 Motivated by such apprehensions, Eisenhower started early by inaugurating several completely new offices that have since become standard features of a White House staff: the chief of staff, the assistant for national security affairs, the cabinet secretary and the staff secretary. Collectively they would make sure that nothing fell through the cracks. These small, carefully contained compartments would be filled with experts solely responsible for their assignments. No White House ever had less leeway for kibitzers.10 Eisenhower also greatly upgraded the office of congressional relations. He was fortunate to have an expert ready for duty. Major General Wilton (Jerry) Persons was a comfortable and conservative Southerner— brother of an Alabama governor—who had been the War Department‘s chief lobbyist during World War II, and, after retirement, had been called back to active duty by Eisenhower when he became SHAPE commander. 4 Bryce Harlow had worked for Persons at the Pentagon and then headed the House Armed Services Committee staff. Gerald Morgan, a Harvard-trained lawyer, had congressional experience drafting the Taft-Hartley Act. Harlow was soon commandeered by the President to be a speechwriter, and his slot was assumed by Jack Martin, the longtime assistant to Senator Robert Taft, who had died in 1953. Over time there were other changes. Morgan became the President‘s counsel in 1955. Martin was made a federal judge in 1958. And when Sherman Adams was forced out in 1958, Persons replaced him as the chief of staff and Harlow became the head of the congressional lobbying unit. Harlow was assisted by Jack Z. Anderson, a colorful former California congressman (and famous pear grower), and Edward McCabe, from the House Committee on Education and Labor, both of whom joined the White House staff in 1956. They were joined in 1959 by Clyde Wheeler, who had been working congressional liaison for the Secretary of Agriculture. Wheeler returned to Oklahoma to run unsuccessfully for Congress in 1960. Two other members of the liaison staff, Earle Chesney and Homer Gruenther, had duties that were more of the ―goodwill‖ nature, such as taking VIPs on tours of the White House. As a group, the congressionalists cast a more conservative shadow than other staff units, a notable division during the 1954 conflict with Senator McCarthy.11 Sherman Adams--Governor to everyone on the staff--had served one term in the House of Representatives. Several others also had had congressional experience.12 But while called upon from time-to-time, they were not meant to backstop the Persons/Harlow shop. They had jobs enough to keep them busy. 5 The modus operandi for dealing with Congress was to let the departments do the heavy lifting. The departments‘ lobbyists had the day-to-day contact with the committees and members and took responsibility for getting legislation passed in a form acceptable to the President. The Persons/Harlow office only conducted a major assault on Capitol Hill once or twice a year. As Harlow told me, ―It‘s rather axiomatic in this work that a president cannot have too many congressional issues that are ‗presidential‘ at one time. Otherwise none of them are presidential, and all of them suffer.‖13 According to McCabe, presidential issues included major tax legislation, the interstate highway program, mutual security, Pentagon reorganization, and labor-management reform.14 The departmental lobbyists gathered on Saturdays at the White House. Recalling these sessions from when he was at Agriculture, Wheeler said, ―Bryce went around the room and asked each of us who we had been talking to on the Hill, who was backing our programs, and who was against us. He always let us have our say before smoothly setting out the Eisenhower agenda and how it affected each agency.‖15 The White House staff also prepared a detailed agenda for the President to use in his weekly meeting with the Republican congressional leaders.16 [space] Those who insist that behind every president there must be some master hypnotist –-a Colonel House or chief of staff or vice president—could not have worked at a White House. I have never met a former staffer who put any stock in Trilby/Svengali theories of the presidency. The guiding force, hidden-hand or otherwise, is in the Oval Office. 6 Part of what defined Dwight Eisenhower was reverence for the separation of powers, a West Point legacy. Yet high regard for The Legislature, Article I, did not extend to members of Congress, whom Ike did not always understand or appreciate. At a Cabinet meeting in early 1956, Brad Patterson recalls, after Eisenhower agreed to send a message on the National Park Service to Congress, he added, ―Well, it‘s like laying pearls before certain animals…‖17 Ike‘s natural home was in Article II, The Executive. It was the type of leadership he had successfully practiced in the army and the university, and he was most comfortable with and most admired other successful executives. His first cabinet was dubbed ―8 millionaires and one plumber‖ by the New Republic.18 (The plumber, Secretary of Labor Martin Durkin, only lasted nine months). There were 21 departmental secretaries in Eisenhower‘s cabinet during his two terms. Only one, Christian Herter, his second secretary of state (1959-61), had ever been elected to Congress.19 And even Herter, like Sherman Adams, had also been a governor.20 Ike did give cabinet status to Senator Henry Cabot Lodge when he appointed him U.S. Representative to the UN. Lodge, his earliest congressional supporter, had just been defeated by John Kennedy. Where the Vice President—or the vice presidency—fit in Eisenhower‘s matrix has an antique feel as viewed through the experiences of more than a half-century. When Dick Cheney claimed in 2007 that he didn‘t have to comply with an executive order on safeguarding classified information because, in fact, his office was part of the legislature, it was greeted as a laugh-line by late night comedians. After all, wasn‘t Cheney supposed to be President Bush‘s Svengali, the most powerful vice president in history? Yet 7 Cheney‘s contention would not have been risible to Dwight Eisenhower. The vice presidency, he wrote in his memoirs, is not ―technically in the Executive branch of government…not subject to presidential orders.‖21 When listing the attendees at a meeting, he locates Vice President Nixon as coming ―from the Senate.‖22 Since he placed the vice presidency in the legislative branch, everything Nixon did for him was on ―a volunteer basis.‖23 Unlike present-day vice presidents, Nixon did not have an office in the White House. He was housed at the Capitol, as was his staff, and their paychecks came from the Senate budget. Nixon was often at the White House for meetings of the cabinet, national security council, legislative leaders, and at other times, but he was not a presence in the West Wing as is today‘s vice president. [space] Dwight Eisenhower was entitled to have been more put off by the ways of Congress than any president since Ulysses S. Grant, the last elected president before Eisenhower not to have been a professional politician; that is, not to have first been a member of Congress, a governor, or in a president‘s cabinet. At his first weekly meeting with the Republican House and Senate leaders, less than a week after his inauguration in 1953, he tells them of his intention to redeem the pledges of the party platform and his campaign. ―To my astonishment, I discovered that some of the men in the room could not seem to understand the seriousness with which I regarded our platform‘s provisions, and were amazed by my uncompromising assertion that I was going to do my best to fulfill every promise to which I had been a party.‖ Thus 8 was his presidential introduction to those he called ―practical politicians‖ (two words he surrounded with quotation marks) ―who laughed off platforms as traps to catch voters.‖24 His next ―sad‖ lesson came when making an appointment that required Senate confirmation. His choice for ambassador to India, former Nebraska Governor Val Peterson, was blocked by his state‘s senators. ―Their objections, they told me, did not involve his personal qualifications or character.‖ It was strictly political. ―This seemed indefensible to me. I told both that I emphatically disapproved of their attitude but I was not going to embarrass Val Peterson and would appoint him to some responsible position where their attitude would be ineffective and his influence more pronounced.‖25 Eisenhower noted in his diary that he was appalled by the ―amount of caution approaching fright that seems to govern the action of most politicians.‖26 After more experiences with congressmen, he wrote, ―These Legislative meetings were sometimes tiresome. Indeed, after a long and wearying discussion with the Legislative leaders one day, I remarked it was about time all of us did something about strengthening whatever sense of humor we might possess….I knew that a sense of humor, though not a guarantee of success, was at least indispensable to sanity.‖ He begins the next paragraph: ―But it was not always easy to laugh.‖27 What should have been troubling is that his party had a majority in only the first two years of his presidency. However, as he told a friend in 1953, ―The particular legislators who are most often opposing Administration views are of the majority party.‖ (He italicized majority.) In this category he put Republican Senators Henry Dworshak and Herman Welker of Idaho, Hugh Butler of Nebraska, George W. Malone of Nevada, William Jenner of Indiana, and Joseph R. McCarthy of Wisconsin.28 He could have added 9 John Bricker of Ohio and Styles Bridges of New Hampshire. Of 13 senators who voted against Charles Bohlen, his nominee for Ambassador to the Soviet Union, 11 were Republicans.29 There were some grim experiences for Eisenhower in his relations with Congress, notably when McCarthy turned his vitriol on Ike‘s beloved army and during an attempt— called the Bricker Amendment—to limit presidential treaty-making powers. But overall the President‘s legislative priorities fared well, founded on a remarkably harmonious relationship with Democratic leaders Sam Rayburn and Lyndon Johnson. Yet, as told by William Ewald, there was a subtext to the Eisenhower-RayburnJohnson trio that tells a great deal about Eisenhower‘s charm, cunning and skills. Ewald helped Eisenhower write his memoirs. Then Ewald, a former White House speechwriter trained in English literature at Harvard, wrote his own book, a fascinating exercise in historiography as he explores what went into Eisenhower‘s memoirs and what did not. Ike told Ewald that he hadn‘t trusted Johnson or Rayburn. On Johnson: ―That fellow‘s such a phony.‖ On Rayburn: ―That fellow would double-cross you.‖30 But in print Eisenhower preferred to tamp down his irritation with legislators, and find reasons to praise them. ―You can‘t trust Mundt,‖ says Eisenhower of the Republican senator from South Dakota; this assessment is in Ewald‘s book, not Eisenhower‘s.31 [space] Because our White House was so compartmentalized, and we were so intent on not minding our colleagues‘ business, the Staff Mess during the Eisenhower years may 10 have played a more important role in creating an atmosphere of collegiality than in other administrations. The Mess was run by the navy, hence the name. As described by Robert Gray, the Cabinet Secretary (1958-61): ―It was located underneath the President‘s office in the basement-level area…. At several tables for four and six, thirty-six diners could be accommodated. Serving hours were twelve noon to 2 p.m. There were no assigned seats, and when a staff member entered the room he could join existing groups or start a new table….Members of the staff joined this exclusive club by purchasing a mess share. They were charged on a per-meal basis, plus a 10 per cent override which went to the staff fund to pay for Christmas, anniversary, and birthday gifts.‖32 Bill Ewald adds: ―A staff member picked up his napkin ring at a shelf to the right as he entered, and he sat down anyplace except at the one table with a titled chair, reserved for Staff Chief Sherman Adams and his guests. After lunch one returned the napkin to its ring: it was washed once a week. Most staff members‘ favorite memento of their White House service is that simple wooden ring bearing one‘s name and ‗White House Mess.‘ Everyone wore a business suit except on Saturdays, the day for a sports jacket.‖ 33 For two years I ate there almost every day. The food was good, inexpensive, convenient, and it was a treat to be educated by the likes of George Kistiakowsky, the great chemist, who was the President‘s science adviser; Clarence Randall, former chairman of Inland Steel and the President‘s adviser on international trade, who became a special friend; Andy Goodpaster, already wise in his early forties, the future NATO commander, who would come out of retirement to rebuild West Point‘s reputation after a cheating scandal; or Press Secretary Jim Hagerty, a man of firm opinions on everything. 11 After awhile I started to jot down our conversations when I returned to my office. My notes are of jokes, recollections, oddities of the day, more serious on days when Eisenhower had a press conference and the audio tape was played for us while we ate. Our talk would not be mistaken for a think tank seminar. Yet this does help answer the question of what Congress looked like from inside the Eisenhower White House. When we talked of John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson, it was because they were running for president, not because they were senators. In over a year I recorded just one serious conversation about Congress (with Ed McCabe of the legislative relations staff). This absence of Congress as a topic of conversation reflected, in part, how Eisenhower cordoned off congressional relations from other operations. This is not the way it had worked under Presidents Roosevelt and Truman, which is exactly what Eisenhower had in mind when he designed his staff system. Then too Eisenhower‘s men, in the manner of their boss, thought of themselves as executives, the Article II folks; they did not wish to be mistaken for coming from Article I, a somewhat louche crowd. In choosing his top White House aide, Ike used the model he appreciated and mastered in a long military career. He would love to have had Bedell Smith, Lucius Clay or Alfred Gruenther as his chief of staff, except that he knew it would cause ―suspicion of excessive military influence.‖34 So he chose the similarly inclined Sherman Adams. While Adams had a difficult reputation on the outside, he was deeply respected within the White House. Staff conformed to the system under which they would advance. The sharp edge between the legislative and executive articles in the Constitution as a governing principle for staffing the White House would start to bend modestly under 12 John Kennedy. He was a senator, but a backbencher, whose time in office, at least since 1956, had been dedicated to running for the president. The personnel curve then bowed when Lyndon Johnson, the Ultimate Legislator, became the President of the United States, merging characteristics that distinguish a congressional staff from a presidential staff. [space] Personality and resume will always play some part in where people fit into the government‘s workforce. But more determining is demand. In 1960, Eisenhower‘s last year, there were 451 top political appointees in the executive agencies, according to Paul C. Light‘s careful count. In 1992, he measured 2,393, a 430 percent increase.35 In 1960, there were 6,866 staff members in congressional offices, according to R. Eric Peterson of the Congressional Research Service. With a sharp increase, partly pushed by the Legislative Reorganization Act of 1970, congressional staffs grew to 17,396 by 2007.36 The creation of aggressive public policy schools in these years would help meet the demand. The lesson was that careers at the political level need not be limited by Article I or Article II. Each new administration, with a plethora of appointments to make, especially if there is a party change, brings new possibilities for congressional staffers and others as well as possibilities on Capitol Hill for those from the outgoing administration. Judging from those around me—a son whose career has been on Capitol Hill and in an agency, his friends, my students, my interns—I see people who think of themselves as ―governmentalists,‖ with career moves determined by opportunity and circumstance, 13 rather than by where a job fits in the constitutional framework. For them Congress will never look like it looked to us from inside the Eisenhower White House. Epilogue What happened to the Eisenhower 88? By noon, January 20, 1961, Jerry Persons had his bags packed and was eager to resume fishing in Florida. The Eisenhower staff was older than most White House staffs—as the President was older than most presidents—and so there would be an aboveaverage number of retirements. Some of the 88—those who had served for some period during two terms—had already left government. Gabriel Hauge, the President‘s initial Assistant for Economic Affairs, was now the chairman of Manufacturers Hanover Trust Company. Howard Pyle was president of the National Safety Council. Charles Willis, one of the young men who had created ―Citizens for Eisenhower‖ in 1952, was the head of Alaska Airlines. Emmet Hughes, the brilliant first term speechwriter, would write two bitter books about the administration. Eisenhower felt betrayed and when crafting his memoirs, according to Ewald, chose to withdraw Hughes‘ paternity from the five most important words of his 1952 campaign: ―I shall go to Korea.‖37 But overwhelmingly Ike‘s former assistants were devoted to their president and would spend their concluding years recalling—and boring their friends—with tales of State Dinners, watching the 4th of July fireworks from the South Lawn, and lunches in the Mess. 14 The academics returned to the academy: Kistiakowsky to Harvard, and then in retirement became an eloquent advocate for banning nuclear weapons; Don Paarlberg, the agricultural economist, who had coordinated the fledgling Food for Peace program, went back to Purdue; Henry Wallich to Yale, until joining the Federal Reserve Board in 1974; Raymond Saulnier, Barnard, lived to be 100, and was photographed for Vanity Fair at 98. Phillip Areeda began a new career as a Harvard Law School professor. He died in 1995 as he was completing the eleventh volume of his life work on antitrust law, of which Stephen Breyer remarked that most lawyers would rather have the support of ―two paragraphs of Areeda on antitrust than four courts of appeals and three Supreme Court Justices.‖38 Allen Wallis became president of the University of Rochester. Malcolm Moos became president of the University of Minnesota. Two staffers stayed in Washington via term appointments. John Bragdon, a classmate of Ike‘s at West Point, was put on the Civil Aeronautics Board. Robert Hampton was given a minority seat on the Civil Service Commission and elevated to chairman when President Nixon took office. Several others returned to Washington with the Nixon presidency, notably Maurice Stans as Secretary of Commerce and Arthur Burns as Chairman of the Federal Reserve. Fewer Eisenhower people remained in Washington, however, than had been or was to be the case with other White House staffs. The primary exceptions were those who had been in congressional liaison. Gerald Morgan joined a law firm, Jack Anderson returned to Capitol Hill to work for the House Veterans Affairs Committee, Edward McCabe became the founding chairman of Sallie Mae, the Student Loan Marketing Association. Bryce Harlow opened a small office for Procter & Gamble and became the 15 gold standard for responsible corporate representation. The major nonprofit foundation in this field is named in his honor. He also became Eisenhower‘s most trusted adviser on all political matters. No member of the Eisenhower 88 would go on to serve in Congress.39 STEPHEN HESS is Senior Fellow Emeritus at the Brookings Institution. He wishes to thank his Eisenhower staff colleagues, Brad Patterson and Bill Ewald, for their ―additions and corrections.‖ ________________________________________________________________________ 1 Frederic Fox (1917-1981), a Congregational minister; White House staff, 1956-61, his duties largely involved writing presidential messages. James Lambie (1914-1999), with Eisenhower from the 1952 campaign through two terms in the White House, his duties largely involved public information programs. Their Staff Book included a summary of major events, a list of all the White House secretaries, photographs of the permanent White House staff, such as the chief telephone operator (Grace Earle), carpenter (Isaac Avery) and chief of the messenger service (Orris Nash). Each copy of the book was numbered; mine was 52. 2 Among the 88, I include three military officers whose jobs were not military in nature: Staff Secretaries Paul (Pete) Carroll (1953-54) and Andrew Goodpaster (1954-61), and Assistant Staff Secretary John Eisenhower (1958-61). A case also can be made for RalphWilliams (1958-61), Assistant Naval Aide, who was importantly involved in speechwriting. 3 College Presidents: Milton Eisenhower (Johns Hopkins), Arthur Fleming (Ohio Wesleyan), Gordon Gray (University of North Carolina), James Killian (MIT), Kevin McCann (Defiance), Harold Stassen (University of Pennsylvania). Generals: John Bragdon, Edward Curtis, Robert Cutler, Wilton Persons, 16 Elwood Quesada, Howard Snyder. Governors: Sherman Adams (New Hampshire), Leo Hoegh (Iowa), Val Peterson (Nebraska), Howard Pyle (Arizona), Harold Stassen (Minnesota). 4 See Kathryn Dunn Tenpas, ―West Wing Shuffle,‖ Washington Post, April 2, 2006; also Matthew J. Dickinson and Kathryn Dunn Tenpas, ―Explaining Increasing Turnover Among Presidential Advisers, 1929-1997,‖ The Journal of Politics, May 2002, pp. 434-448. 5 Mary Jane McCaffree, White House Social Secretary, 1953-61; Anne Wheaton, Associate Press Secretary, 1957-61; Ann Whitman, Secretary to the President, 1953-61. Fred Morrow, Administrative Officer, 1955-61. Morrow‘s diary has been published as Black Man in the White House (Macfadden Books, 1963). 6 The others were Stephen Benedict, 26 (1952 campaign to 1955), Douglas Price, 28 (1952 campaign, White House 1957-61), William Ewald, 29 (1954-56), H. Roemer McPhee, 29 (1954-61). 7 See his The Ring of Power (Basic Books, 1988), The White House Staff (Brookings, 2000), and To Serve the President (Brookings, 2008). A career civil servant, Patterson was detailed to the White House Secretariat in 1954 and became Assistant Cabinet Secretary in 1955. 8 Professor Moos arranged to have me paid by the Republican National Committee for the first four months so that I didn‘t formally go on the White House payroll until February, 1959. The first time some of my words were spoken by President Eisenhower was September 26, 1958, ―Address at the Fort Ligonier Bicentennial Celebration, Ligonier, Pennsylvania.‖ 9 Dwight Eisenhower, Mandate for Change (Doubleday, 1963), pp. 87 and 114. 10 Yet Ike, on occasion, created a White House assignment when he perceived a deficiency in the Cabinet. This was especially true in foreign policy where he added special assistants C.D. Jackson and Nelson Rockefeller to try to get the ―bold, new ideas‖ that were not coming from Secretary of State John Foster Dulles. See Stephen Hess, Organizing the Presidency (3rd edition, Brookings, 2002), p. 62. 11 See William Bragg Ewald, Jr., Eisenhower the President (Prentice-Hall, 1981), p. 124. 12 Cabinet Secretary Max Rabb, 1954-58, had been an assistant to Massachusetts Senators Henry Cabot Lodge and Sinclair Weeks before World War II. Fred Seaton served less than a year in the Senate by appointment. He was on the White House staff, 1955-56, before Eisenhower made him Secretary of the Interior. Appointments Secretary Tom Stephens was with John Foster Dulles during his four-month career as a senator from New York in 1949. And Oregon Congressman Harris Ellsworth, defeated in 1956, was made Chairman of the U.S. Civil Service Commission, 1957-59, a job that came with the title of President‘s Advisor on Personnel Management. 13 Harlow interview with author, 1976. 14 Cited in Bob Burke and Ralph G. Thompson, Bryce Harlow (Oklahoma Heritage Association, 2000), p. 96. 15 Ibid, p. 95. 16 For details on Eisenhower‘s legislative liaison operation, see Ken Collier, Between the Branches: The White House Office of Legislative Affairs (University of Pittsburgh Press, 1997), pp. 29-56. 17 Letter to author, December 12, 2009. 18 ―Washington Wire,‖ December 15, 1952, p. 3. 17 19 As a comparison, there were four members of Congress in President Obama‘s initial cabinet and he made offers to three others. 20 A bit of cabinet trivia: The Eisenhower cabinet also included three men who had been appointed to the Senate: John Foster Dulles, Secretary of State (1953-59), was appointed to the Senate to fill the vacancy caused by the resignation of Robert Wagner of New York and served from July 7, 1949, to November 8, 1949; Sinclair Weeks, Secretary of Commerce (1953-58), was appointed to the Senate to fill the vacancy caused by the resignation of Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts and served from February 8, 1944 to December 19, 1944; Fred Seaton, Secretary of the Interior (1956-61), was appointed to the Senate to fill the vacancy caused by the death of Kenneth Wherry of Nebraska and served from December 10, 1951 to November 4, 1952. 21 Mandate for Change, pp. 540-41. 22 Ibid., p. 194. 23 Dwight Eisenhower, Waging Peace (Doubleday, 1965), p. 6. 24 Mandate for Change, pp. 194-95. 25 Ibid., p. 119. Peterson was then named Federal Civil Defense Administrator. Eisenhower goes on to propose ―an amendment to the Constitution providing that any nomination within the Executive branch only—excluding judges, appointees to regulatory commissions, and the like—should be automatic unless, by a two-thirds majority, the Senate should reject it.‖ 26 Quoted in Ken Collier, ―Eisenhower and Congress: The Autopilot Presidency,‖ in Presidential Studies Quarterly, Spring 1994, p. 321. 27 28 Ibid., p. 300. Ibid., 193. 29 Ibid., p. 213. The senators were John Bricker, Styles Bridges, Everett Dirksen, Henry Dworshak, Barry Goldwater, Bourke Hickenlooper, George Malone, Joseph McCarthy, Karl Mundt, Andrew Schoeppel, and Herman Welker. 30 See Ewald, pp. 27-28. 31 Ibid, p. 134. 32 Robert Keith Gray, Eighteen Acres Under Glass (Doubleday, 1962), p. 34. 33 Ewald, op. cit., p. 4. 34 Mandate for Change, pp. 88-89. 35 Paul C. Light, Thickening Government (Brookings, 1995), p. 192. 36 R. Eric Peterson, ―Legislative Branch Staffing, 1954-2007,‖ Congressional Research Service Report R40056, October 15, 2008, pp. 1-4. 37 38 Ewald, op. cit., pp. 224-5. David Binder, ―Phillip Areeda, Harvard Law Professor and Antitrust Expert, Dies at 65,‖ New York Times, December 27, 1995. 18 39 There were, however, three political appointees from the departments who were elected to Congress: Ted Sevens (Interior), Steve Horn (Labor), and John V. Lindsay (Justice).