Rare Case of the Vietnamese Time Bomb!

advertisement

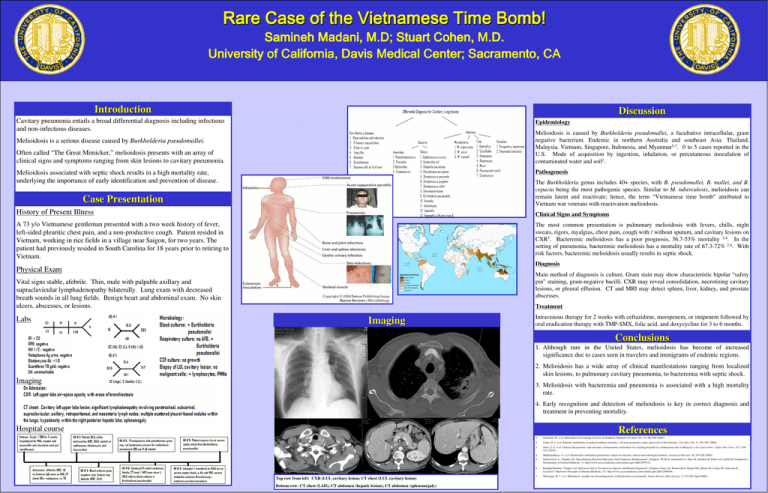

Rare Case of the Vietnamese Time Bomb! Samineh Madani, Madani, M.D; Stuart Cohen, M.D. University of California, Davis Medical Center; Sacramento, CA Introduction Discussion Cavitary pneumonia entails a broad differential diagnosis including infectious and non-infectious diseases. Epidemiology Melioidosis is caused by Burkholderia pseudomallei, a facultative intracellular, gram negative bacterium. Endemic in northern Australia and southeast Asia: Thailand, Malaysia, Vietnam, Singapore, Indonesia, and Myanmar5-7. 0 to 5 cases reported in the U.S. Mode of acquisition by ingestion, inhalation, or percutaneous inoculation of contaminated water and soil1. Melioidosis is a serious disease caused by Burkholderia pseudomallei. Often called “The Great Mimicker,” melioidosis presents with an array of clinical signs and symptoms ranging from skin lesions to cavitary pneumonia. Pathogenesis Melioidosis associated with septic shock results in a high mortality rate, underlying the importance of early identification and prevention of disease. The Burkholderia genus includes 40+ species, with B. pseudomallei, B. mallei, and B. cepacia being the most pathogenic species. Similar to M. tuberculosis, melioidosis can remain latent and reactivate; hence, the term “Vietnamese time bomb” attributed to Vietnam war veterans with reactivation melioidosis. Case Presentation History of Present Illness Clinical Signs and Symptoms A 73 y/o Vietnamese gentleman presented with a two week history of fever, left-sided pleuritic chest pain, and a non-productive cough. Patient resided in Vietnam, working in rice fields in a village near Saigon, for two years. The patient had previously resided in South Carolina for 18 years prior to retiring to Vietnam. The most common presentation is pulmonary melioidosis with fevers, chills, night sweats, rigors, myalgias, chest pain, cough with / without sputum, and cavitary lesions on CXR3. Bacteremic melioidosis has a poor prognosis, 36.7-53% mortality 2,4. In the setting of pneumonia, bacteremic melioidosis has a mortality rate of 67.3-72% 2,4. With risk factors, bacteremic melioidosis usually results in septic shock. Diagnosis Physical Exam Main method of diagnosis is culture. Gram stain may show characteristic bipolar “safety pin” staining, gram-negative bacilli. CXR may reveal consolidation, necrotizing cavitary lesions, or pleural effusion. CT and MRI may detect spleen, liver, kidney, and prostate abscesses. Vital signs stable, afebrile. Thin, male with palpable axillary and supraclavicular lymphadenopathy bilaterally. Lung exam with decreased breath sounds in all lung fields. Benign heart and abdominal exam. No skin ulcers, abscesses, or lesions. Labs Treatment Imaging Intravenous therapy for 2 weeks with ceftazidime, meropenem, or imipenem followed by oral eradication therapy with TMP-SMX, folic acid, and doxycycline for 3 to 6 months. Conclusions 1. Although rare in the United States, melioidosis has become of increased significance due to cases seen in travelers and immigrants of endemic regions. 2. Melioidosis has a wide array of clinical manifestations ranging from localized skin lesions, to pulmonary cavitary pneumonia, to bacteremia with septic shock. Imaging 3. Melioidosis with bacteremia and pneumonia is associated with a high mortality rate. 4. Early recognition and detection of melioidosis is key in correct diagnosis and treatment in preventing mortality. Hospital course References Top row from left: CXR (LUL cavitary lesion; CT chest (LUL cavitary lesion) Bottom row: CT chest (LAD); CT abdomen (hepatic lesion); CT abdomen (splenomegaly) 1. Chierakul, W. et al. Melioidosis in 6 tsunami survivors in Southern Thailand. Clin Infect Dis. 41, 982-990 (2005). 2. Currie, B. J. et al. Endemic melioidosis in tropical northern Australia: a 10-year prospective study and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 31, 981-987 (2000). 3. Deris, Z. Z. et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of bacteraemic melioidosis in a teaching hospital in a northeastern state of Malaysia: a five year review. J Infect Dev Ctries. 4(7), 430435. (2010). 4. Mukhopadhyay, A. et al. Bacteraemic melioidosis pneumonia: impact on outcome, clinical and radiological features. Journal of Infection. 48, 334-338 (2004). 5. Norton Scott A, "Chapter 183. Miscellaneous Bacterial Infections with Cutaneous Manifestations" (Chapter). Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest B, Paller AS, Leffell DJ: Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine, 7e: http://www.accessmedicine.com/content.aspx?aID=2995332. 6. Ramphal Reuben, "Chapter 145. Infections Due to Pseudomonas Species and Related Organisms” (Chapter). Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J: Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 17e: http://www.accessmedicine.com/content.aspx?aID=2894658. 7. Wiersinga, W. J. et al. Melioidosis: insights into the pathogenicity of Burkholderia pseudomallei. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 4, 272-282 (April 2006).