Testimony of Michael A. Wermuth Senior Policy Analyst The RAND Corporation

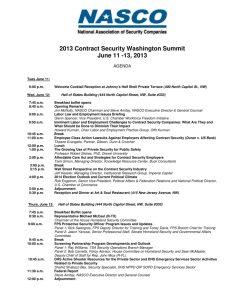

advertisement