Chemical Science “Chemistry – our life, our future”

advertisement

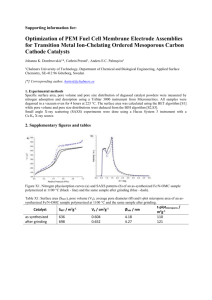

Chemical Science RSC Events – reflecting the global nature of science “Chemistry – our life, our future” www.rsc.org/chemicalscience Volume 2 | Number 1 | 1 January 2011 | Pages 1–180 RSC Events 2011 Join the world’s leading scientists to share knowledge and information within the chemical sciences Antibiotics 2011 - Where Now? 20 January 2011, London, UK Registration deadline 17 December 2010 www.rsc.org/antibiotics11 Frontiers in Spectroscopy (Faraday Discussion 150) 6 - 8 April 2011, Basel, Switzerland Poster abstracts by 4 February 2011 Registration deadline 4 March 2011 www.rsc.org/fd150 1st International Conference on Clean Energy 10 - 13 April 2011, Dalian, China Poster abstracts by 31 January 2011 Registration deadline 11 March 2011 www.icce.cas.cn EICC-1: First EuCheMS Inorganic Chemistry Conference 11 - 14 April 2011, Manchester, UK Poster abstracts by 4 February 2011 Registration deadline 4 March 2011 www.rsc.org/EICC1 Hydrogen Storage Materials (Faraday Discussion 151) 18 - 20 April 2011, Didcot, Oxon, UK Poster abstracts by 18 February 2011 Registration deadline 18 March 2011 www.rsc.org/FD151 6th International Symposium on Macrocyclic and Supramolecular Chemistry (6-ISMSC) 3 - 7 July 2011, Brighton, UK Poster abstracts by 29 April 2011 Registration deadline 3 June 2011 www.ISMSC2011.org ISSN 2041-6520 Gold (Faraday Discussion 152) 4 - 6 July 2011, Cardiff, UK Poster abstracts by 30 April 2011 Registration deadline 3 June 2011 www.rsc.org/FD152 Challenges in Chemical Biology (ISACS5) 26 - 29 July 2011, Manchester, UK Poster abstracts by 27 May 2011 Registration deadline 24 June 2011 www.rsc.org/ISACS5 10th International Conference on Materials Chemistry (MC10) 4 - 7 July 2011, Manchester, UK Poster abstracts by 6 May 2011 Registration deadline 10 June 2011 www.rsc.org/MC10 Ionic Liquids (Faraday Discussion 154) 22 - 24 August 2011, Belfast, UK Poster abstracts by 17 June 2011 Registration deadline 15 July 2011 www.rsc.org/FD154 Challenges in Renewable Energy (ISACS4) 5 - 8 July 2011, MIT, Boston, USA Poster abstracts by 6 May 2011 Registration deadline 3 June 2011 www.rsc.org/ISACS4 22nd International Symposium: Synthesis in Organic Chemistry 11 - 14 July 2011, Cambridge, UK Poster abstracts by 27 May 2011 Registration deadline 24 June 2011 www.rsc.org/OS11 Coherence and Control in Chemistry (Faraday Discussion 153) 25 - 27 July 2011, Leeds, UK Poster abstracts by 30 May 2011 Registration deadline 27 June 2011 www.rsc.org/FD153 Analytical Research Forum 2011 25 - 27 July 2011, Manchester, UK Poster abstracts by 27 May 2011 Registration deadline 24 June 2011 www.rsc.org/ARF11 Challenges in Organic Materials & Supramolecular Chemistry (ISACS6) 2 - 5 September 2011, Beijing, China Poster abstracts by 8 July 2011 Registration deadline 5 August 2011 www.rsc.org/ISACS6 Artificial Photosynthesis (Faraday Discussion 155) 5 - 7 September 2011, Edinburgh, UK Poster abstracts by 1 July 2011 Registration deadline 5 August 2011 www.rsc.org/FD155 Don’t miss out on this year’s exciting events... See individual websites for full details or contact RSC Events at events@rsc.org or +44 (0)1223 432254/432380 The RSC organises a wide range of other specialist events – further information can be found on our website www.rsc.org/events www.rsc.org/events EDGE ARTICLE Hong-Cai Zhou et al. A stepwise transition from microporosity to mesoporosity in metal-organic frameworks by thermal treatment Registered Charity Number 207890 Chemical Science C Dynamic Article Links < Cite this: Chem. Sci., 2011, 2, 103 EDGE ARTICLE www.rsc.org/chemicalscience A stepwise transition from microporosity to mesoporosity in metal–organic frameworks by thermal treatment† Daqiang Yuan,a Dan Zhao,a Daren J. Timmonsb and Hong-Cai Zhou*a Received 28th May 2010, Accepted 2nd October 2010 DOI: 10.1039/c0sc00320d A Cd MOF with twisted partially augmented the net was synthesized. Activation at increasing temperatures revealed an unprecedented stepwise transition from microporosity to mesoporosity. This thermal treatment may serve as an alternative approach for the preparation of mesoporous MOFs. Introduction As defined by IUPAC, mesoporous materials have pore sizes in 1 Compared to their microporous the range of 20–500 A. mesoporous counterparts whose pore sizes are less than 20 A, materials are more desirable in host–guest chemistry, mostly because they can accommodate larger guest molecules.2 In recent years, remarkable progress has been made in the design and synthesis of silica-based mesoporous materials, which were widely applied in catalysis, sorption, chromatography, and controlled release of guest molecules.3 As newly emerging porous crystalline materials, metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) have demonstrated their potency in gas storage and gas separation.4 However, limited progress has been made in the discovery of new mesoporous MOFs.5 As part of our ongoing work towards stable mesoporous MOFs, we reported mesoMOF-1, whose mesoporosity was retained by turning the framework into ionic by neutralization treatment.5d Herein we report another mesoporous MOF (mesoMOF-2), which is prepared by thermal treatment. This process may serve as an alternative approach for preparing mesoporous MOFs. TGA-50 TGA, with a heating rate of 5 C min1. Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns were obtained on a XPert Pro MPD. Mass spectra were obtained on a VG analytical 70S high resolution, double focusing, sectored (EB) mass spectrometer at the center for TAMU Laboratory for Biological Mass Spectrometry. TGA-MS analyses were performed in STA449C-QMS 403 C Thermal Analysis-Quadrupole Mass Spectrometer. IR spectra (KBr plates) were measured on a Nicolet 740 FTIR spectrometer. MesoMOF-2 synthesis Benzo-(1,2;3,4;5,6)-tris(thiophene-20 -carboxylic acid) (H3BTTC)6 (100 mg, 1.6 104 mol) and Cd(NO3)2$4H2O (300 mg, 1.3 103 mol) were dissolved in 15 mL of dimethylacetamide (DMA) with 20 drops of HBF4 (40%) in a vial. The vial was tightly capped and placed in a 100 C oven for 72 h to yield 218 mg of pale yellow cubic crystals (yield: 76% based on H3BTTC). The crystal has a formula of Cd13(BTTC)8(OH)2(H2O)16$18DMA, which was derived from crystallographic data,‡ elemental analysis (% calc/found: C 36.28/36.96, H 3.52/ 3.65, N 3.97/3.91), and TGA. Experimental section Adsorption experiments General information N2 and Ar physisorption isotherms were measured up to 1 bar using a Micromeritics ASAP 2020 surface area and pore size analyzer. An as-isolated sample of mesoMOF-2 was soaked in dichloromethane, sonicated for 20 min, and then replaced with fresh dichloromethane after 12 h. This process was repeated for up to 60 h to completely wash out any residual unreacted ligand and DMA in the pores. After the removal of dichloromethane by decanting, the sample was activated by drying under a dynamic vacuum at room temperature overnight. Before the measurement, the sample was dried again by using the ‘‘outgas’’ function of the surface area analyzer for 2 h at a different temperature. High-purity gases were used (N2: 99.999%, Ar: 99.999%). Pore size distribution data were calculated from the N2 sorption isotherms based on DFT model in the Micromeritics ASAP2020 software package (assuming slit pore geometry). Commercially available reagents were used as received. Elemental analyses (C, H, and N) were obtained from Canadian Microanalytical Service, Ltd. 1H NMR data were collected on a Mercury 300 MHz NMR spectrometer. Thermogravimetry analyses (TGA) were performed under N2 on a SHIMADZU a Department of Chemistry, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, 77843, USA. E-mail: zhou@mail.chem.tamu.edu; Fax: +1 979 845 4719; Tel: +1 979 845 4034 b Department of Chemistry, Virginia Military Institute, Lexington, VA, 24450, USA. E-mail: TimmonsDJ@vmi.edu; Fax: +1 540 464 7261 † Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: Extra figures, N2 & Ar sorption isotherms, pore volume data, TGA-MS. CCDC reference number 762237. For ESI and crystallographic data in CIF or other electronic format see DOI: 10.1039/c0sc00320d This journal is ª The Royal Society of Chemistry 2011 Chem. Sci., 2011, 2, 103–106 | 103 Single crystal X-ray study Single crystal X-ray data of mesoMOF-2 were collected on a Bruker AXS Smart III X-ray diffractometer outfitted with a Mo X-ray source and an APEX II CCD detector equipped with an Oxford Cryostream low temperature device. The APEX-II software suite was used for data collection, cell refinement, reduction, and absorption correction. Structures of mesoMOF-2 were solved by direct method and refined by full-matrix leastsquares on F2 using SHELXTL.7 Non-hydrogen atoms were refined with anisotropic displacement parameters during the final cycles. Organic hydrogen atoms were placed in calculated positions with isotropic displacement parameters set to 1.2 Ueq of the attached atom. The solvent molecules of mesoMOF-2 are highly disordered, and attempts to locate and refine the solvent peaks were unsuccessful. Contributions to scattering due to these solvent molecules were removed using the SQUEEZE routine of PLATON structures were then refined again using the data generated.8 Result and discussion X-ray diffraction studies reveal that mesoMOF-2 crystallizes in cubic space group Fm-3c, a rare space group for MOFs.9 As can be seen in Fig. 1b, four Cd atoms are bridged by eight carboxylates to form the rare square-planar tetranuclear cadmium secondary building unit (SBU). All four Cd atoms in the SBU are seven-coordinated with capped triangular prism geometry. Each SBU connects eight BTTC ligands, and each BTTC binds three SBUs to form a twisted truncated-octahedral cage with [Cd(OH)2(H2O)4] situated inside the cage (Fig. 1c). In this cage, the six vertices are occupied by SBUs, and all eight faces are spanned by the BTTC ligands, leaving almost no entrance for small molecules. An icosahedral-type cavity (Fig. 1d) is formed by simple cubic packing of eight cages (Fig. 1e), giving rise to a zeolite-like (ITQ-21) structure.10 The internal surface can be Fig. 1 (a) The BTTC ligand (Red: O; Grey: C; Yellow: S). (b) The tetranuclear cadmium SBU (Green: Cd). (c) The twisted truncatedoctahedral cage [4668] with [Cd(OH)2(H2O)4] situated inside. (d) The icosahedral-type cavity [320] (the distance between opposite vertices is (e) Polyhedra 3D packing in mesoMOF-2. (f) The window and 25.8 A). cavity in mesoMOF-2 simplified by the Schwarz P surface model. 104 | Chem. Sci., 2011, 2, 103–106 simplified by the Schwarz P model, in which large cavities measured O/O) are interconnected through (diameter 18.4 A, measured O/O) (Fig. 1f). small windows (diameter 12.2 A, Topology analysis by the Topos 4.0 program suggests the (43;62;8)3(63) topology symbol, which belongs to a twisted partially augmented the net (Figure S1†).11 In order to confirm its permanent porosity, N2 and Ar sorption isotherms were collected (Figure S2 and Figure S3†). After activation at 30 C, the N2 sorption isotherm of mesoMOF-2 shows typical Type I behavior, indicating a microporous structure, with a BET surface area of 842 m2 g1 (Langmuir surface area 1022 m2 g1) and a total pore volume of 0.364 cm3 g1. Interestingly, gradually increasing the activation temperature to 230 C reveals a step-by-step transition from Type I to Type IV isotherm with an increasingly obvious H2 hysteresis loop (Fig. 2a). The same trend is also observed in Ar isotherms. Because hysteresis loops are normally associated with mesopores, it appears that the pore size increases as the activation temperature becomes higher. This pore size increase is supported by the pore size distribution data obtained by nonlocal density functional theory (NLDFT) (Fig. 2b). At low activation the temperature (30 C), the smallest pore size detected is 5.9 A, largest one is 25.2 A, with the highest pore size distributes at These data correspond well with the crystal model. At 11.8 A. a higher activation temperature (50 C), the largest pore size Further increase of the activation temperature to reaches 37.0 A. but the most abundant 220 C enlarges the largest pore (63.4 A), Fig. 2 (a) Nitrogen isotherms measured at 77 K for mesoMOF-2 activated at different temperature. (b) Pore size distribution of mesoMOF-2 activated at different temperature. This journal is ª The Royal Society of Chemistry 2011 It is evident that there is pore still remains the same size (11.8 A). a stepwise transition from microporosity to mesoporosity in this framework upon increased activation temperature. It is tempting to attribute this porosity transition to the framework deterioration at higher temperature. Such a conclusion, however, can not explain the following experimental data convincingly. First of all, the deteriorated framework should have weakened X-ray diffraction due to the loss of periodicity. Nevertheless, the twisted partially augmented the net in mesoMOF-2 is very robust and is maintained even after heating at 250 C, which is proved by powder X-ray diffraction studies (Fig. 3). Additionally, single crystal X-ray scattering spots can still be harvested on a sample crystal activated at 220 C (Figure S4†). The crystal structure can be solved using these data, unveiling a similar structure with the as-synthesized crystal. This unexpected framework stability may result from the cage packing geometry (Fig. 1e).5m Besides, framework deterioration normally leads to lower pore volumes. In mesoMOF-2, however, there is a steady increase in pore volume as the activation temperature elevates to 220 C (Figure S5†). Such pore volume enhancement can not be simply attributed to framework deterioration. Another possible reason for this porosity transition is a gradual removal of unreacted H3BTTC and solvent molecules in the channels. Once again, this reasoning is not convincing. First of all, without any guest molecule, the largest cavity in (measured Cd/Cd). This mesoMOF-2 has a diameter of 24.1 A is much smaller than the experimental pore size distribution data. Secondly, we used a much larger metal/ligand ratio (8.125 : 1) to ensure the complete depletion of ligand during the reaction (the theoretical metal/ligand ratio is only 1.625 : 1). Before being activated under vacuum, the fresh sample was subjected to rigorous solvent exchange to completely wash out any residual unreacted ligand and DMA in the pores. As can be seen from the IR spectrum of the activated sample (Fig. 4), the absorption peak corresponding to carboxyl group vibration from the uncomplexed H3BTTC (1650 cm1) is absent. In addition, the peak corresponding to carbonyl group vibration (1610 cm1) from DMA in the fresh sample is almost invisible in the activated sample, indicating near complete removal of solvent in the Fig. 3 Powder X-ray diffraction patterns of mesoMOF-2 heated at different temperature. This journal is ª The Royal Society of Chemistry 2011 Fig. 4 IR spectra of uncomplexed ligand (H3BTTC), terthienobenzene, as-synthesized sample, and samples activated at 30 C and 220 C. activated sample. Additional evidence comes from the elemental analyses. The theoretical sulfur content in a completely activated mesoMOF-2 framework is 15.11 wt%, assuming no loss of terthienobenzene, and 23.21 wt% in pure ligand (H3BTTC$2H2O). Therefore, if the framework has unreacted ligand within, the sulfur content should be between these two values. However, the sulfur content in the sample activated at 30 C is only 11.56 wt%, indicating no residual ligand within channels and the partial loss of terthienobenzene. It has been reported that H3BTTC can undergo decarboxylation to liberate terthienobenzene by heating.6 Indeed, we observed trace amount of white crystalline powder sublimed to the upper inner wall of the sample tube after gas sorption measurements. Analysis of the white powder by 1H-NMR and EI-MS confirmed the presence of terthienobenzene (Fig. 5). TGA-MS of mesoMOF-2 fully exchanged with dichloromethane and dried was measured. The signal of trivalent anion of the terthienobenzene was clearly identified upon heating (Figure S6†). Since there is no free H3BTTC within the channels, the detected terthienobenzene should come from the decarboxylated BTTC ligand within the framework. In mesoMOF-2, the BTTC ligand serves as the pore wall. Their decarboxylation will open up the twisted truncated-octahedral cages (Fig. 1c) which are inaccessible at first. The opening of these cages leads to the incremental increase of pore diameter and stepwise transition Fig. 5 1H-NMR and EI-MS data of sublimed terthienobenzene after gas sorption measurements. Chem. Sci., 2011, 2, 103–106 | 105 from microporosity to mesoporosity in the framework. It is likely that the framework remains intact during the initial BTTC decarboxylation allowing the pore volume to increase steadily with increasing activation temperature until 220 C. When the temperature is increased further (230 C), the framework begins to collapse accounting for the reduced pore volume. Further evidence comes from the sample mass change after each activation. According to Figure S8,† the sample mass reduction before 50 C is contributed by the residual solvent. From 50 C to 120 C, the sample mass barely changes. When the temperature went above 120 C, a substantial mass reduction was observed, which is contributed by the loss of externally coordinated water (theoretical weight percent: 4.51 wt%) and terthienobenzene unit (theoretical weight percent: 41.20 wt%). As can be seen from Figure S9,† further activation of the sample at 230 C over a period of time would reveal a further mass reduction up to 54.26 wt%, which corresponds well with the theoretical mass loss of all the coordinated water and terthienobenzene unit (48.01 wt%). Since activation conditions and activation time are both involved in this process, it is hard to determine how much terthienobenzene the framework can lose before it degrades. Further activation at 230 C definitely leads to additional terthienobenzene loss (Figure S9†). However, this does not necessarily give rise to an increase in mesoporosity, because the framework starts to collapse once a certain amount of terthienobenzene is lost (Figure S10†). This process is irreversible because of the covalent bond breaking during the thermal treatment. Conclusions In this report, a thermally controlled stepwise transition from microporosity to mesoporosity in MOFs was found. This thermal treatment may serve as an alternative approach towards mesoporous MOFs with three prerequisites: (1) ligand prone to decomposition; (2) volatile fragments can be liberated during thermal activation; and (3) robust framework to prevent framework disintegration. Further studies will be focused on applying this approach to generate more mesoporous MOFs and their subsequent applications in host–guest chemistry. Acknowledgements This material is based upon work supported as part of the Center for Gas Separations Relevant to Clean Energy Technologies, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the U. S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Award Number DE-SC0001015. Notes and references ‡ Crystal data for MesoMOF-2: C120H60Cd13O66S24, Mr ¼ 4788.32, 0.16 0.15 0.14 mm3, cubic, space group Fm-3c (No. 226), a ¼ 39.2048(18), 3, Z ¼ 8, Dc ¼ 1.056 g cm3, F000 ¼ 18528, Mo-Ka V ¼ 60258(5) A T ¼ 173(2) K, 2q ¼ 55.8 , 102342 reflections radiation, l ¼ 0.71073 A, collected, 3156 unique (Rint ¼ 0.0984). Final GooF ¼ 1.152, R1 ¼ 0.0648, wR2 ¼ 0.1561, R indices based on 2957 reflections with I > 2s(I), 88 parameters, 6 restraints. CCDC 762237 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. 106 | Chem. Sci., 2011, 2, 103–106 1 K. S. W. Sing, D. H. Everett, R. A. W. Haul, L. Moscou, R. A. Pierotti, J. Rouquerol and T. Siemieniewska, Pure Appl. Chem., 1985, 57, 603–619. 2 (a) M. E. Davis, Nature, 2002, 417, 813–821; (b) A. Corma, Chem. Rev., 1997, 97, 2373–2419; (c) T. J. Barton, L. M. Bull, W. G. Klemperer, D. A. Loy, B. McEnaney, M. Misono, P. A. Monson, G. Pez, G. W. Scherer, J. C. Vartuli and O. M. Yaghi, Chem. Mater., 1999, 11, 2633–2656. 3 (a) Y. Wan and D. Y. Zhao, Chem. Rev., 2007, 107, 2821–2860; (b) F. Hoffmann, M. Cornelius, J. Morell and M. Froba, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 2006, 45, 3216–3251; (c) Y. S. Tao, H. Kanoh, L. Abrams and K. Kaneko, Chem. Rev., 2006, 106, 896–910; (d) P. Selvam, S. K. Bhatia and C. G. Sonwane, Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., 2001, 40, 3237–3261. 4 (a) N. L. Rosi, J. Eckert, M. Eddaoudi, D. T. Vodak, J. Kim, M. O’Keeffe and O. M. Yaghi, Science, 2003, 300, 1127–1129; (b) M. Dinca, A. Dailly, Y. Liu, C. M. Brown, D. A. Neumann and J. R. Long, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2006, 128, 16876–16883; (c) X. Lin, I. Telepeni, A. J. Blake, A. Dailly, C. M. Brown, J. M. Simmons, M. Zoppi, G. S. Walker, K. M. Thomas, T. J. Mays, P. Hubberstey, N. R. Champness and M. Schroder, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2009, 131, 2159–2171; (d) A. R. Millward and O. M. Yaghi, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2005, 127, 17998–17999; (e) P. L. Llewellyn, S. Bourrelly, C. Serre, A. Vimont, M. Daturi, L. Hamon, G. De Weireld, J. S. Chang, D. Y. Hong, Y. K. Hwang, S. H. Jhung and G. Ferey, Langmuir, 2008, 24, 7245–7250; (f) S. Q. Ma, D. F. Sun, J. M. Simmons, C. D. Collier, D. Q. Yuan and H. C. Zhou, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2008, 130, 1012–1016; (g) D. Zhao, D. Q. Yuan and H. C. Zhou, Energy Environ. Sci., 2008, 1, 222–235; (h) S. Q. Ma and H. C. Zhou, Chem. Commun., 2010, 46, 44–53; (i) H. Bux, F. Y. Liang, Y. S. Li, J. Cravillon, M. Wiebcke and J. Caro, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2009, 131, 16000–16001; (j) J. R. Li, R. J. Kuppler and H. C. Zhou, Chem. Soc. Rev., 2009, 38, 1477–1504. 5 (a) G. Ferey, C. Mellot-Draznieks, C. Serre and F. Millange, Acc. Chem. Res., 2005, 38, 217–225; (b) G. Ferey, C. Mellot-Draznieks, C. Serre, F. Millange, J. Dutour, S. Surble and I. Margiolaki, Science, 2005, 309, 2040–2042; (c) B. Wang, A. P. C^ ote, H. Furukawa, M. O’Keeffe and O. M. Yaghi, Nature, 2008, 453, 207–212; (d) X. S. Wang, S. Q. Ma, D. F. Sun, S. Parkin and H. C. Zhou, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2006, 128, 16474–16475; (e) Q. R. Fang, G. S. Zhu, Z. Jin, Y. Y. Ji, J. W. Ye, M. Xue, H. Yang, Y. Wang and S. L. Qiu, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 2007, 46, 6638–6642; (f) Y. K. Park, S. B. Choi, H. Kim, K. Kim, B. H. Won, K. Choi, J. S. Choi, W. S. Ahn, N. Won, S. Kim, D. H. Jung, S. H. Choi, G. H. Kim, S. S. Cha, Y. H. Jhon, J. K. Yang and J. Kim, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 2007, 46, 8230–8233; (g) L. G. Qiu, T. Xu, Z. Q. Li, W. Wang, Y. Wu, X. Jiang, X. Y. Tian and L. D. Zhang, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 2008, 47, 9487–9491; (h) K. Koh, A. G. Wong-Foy and A. J. Matzger, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 2008, 47, 677–680; (i) F. Nouar, J. F. Eubank, T. Bousquet, L. Wojtas, M. J. Zaworotko and M. Eddaoudi, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2008, 130, 1833–1835; (j) N. Klein, I. Senkovska, K. Gedrich, U. Stoeck, A. Henschel, U. Mueller and S. Kaskel, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 2009, 48, 9954–9957; (k) A. Sonnauer, F. Hoffmann, M. Froba, L. Kienle, V. Duppel, M. Thommes, C. Serre, G. Ferey and N. Stock, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 2009, 48, 3791–3794; (l) K. Koh, A. G. Wong-Foy and A. J. Matzger, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2009, 131, 4184–4185; (m) D. Zhao, D. Q. Yuan, D. F. Sun and H. C. Zhou, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2009, 131, 9186–9188; (n) D. Y. Hong, Y. K. Hwang, C. Serre, G. Ferey and J. S. Chang, Adv. Funct. Mater., 2009, 19, 1537–1552; (o) Y. Yan, X. Lin, S. H. Yang, A. J. Blake, A. Dailly, N. R. Champness, P. Hubberstey and M. Schr€ oder, Chem. Commun., 2009, 1025–1027. 6 T. Taerum, O. Lukoyanova, R. G. Wylie and D. F. Perepichka, Org. Lett., 2009, 11, 3230–3233. 7 G. M. Sheldrick, Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A: Found. Crystallogr., 2008, 64, 112–122. 8 A. L. Spek, J. Appl. Crystallogr., 2003, 36, 7–13. 9 S. Das, H. Kim and K. Kim, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2009, 131, 3814–3815. 10 A. Corma, M. Diaz-Cabanas, J. Martinez-Triguero, F. Rey and J. Rius, Nature, 2002, 418, 514–517. 11 V. A. Blatov, IUCr CompComm Newsletter, 2006, 7, 4–38. This journal is ª The Royal Society of Chemistry 2011