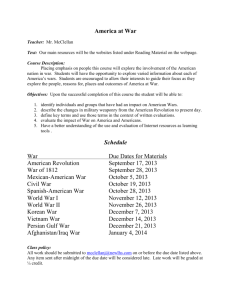

F International Confl ict Resolution From Practice to Knowledge and Back Again

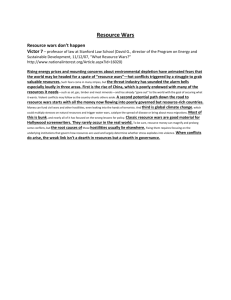

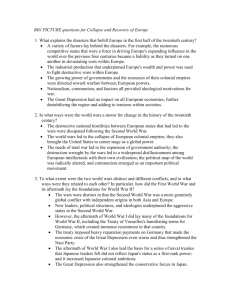

advertisement