Document 13215478

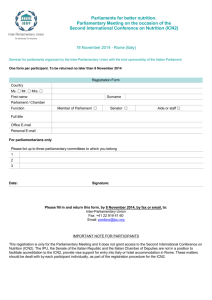

advertisement