The Republican Citizen rgrr 48

advertisement

48

THE

rgrr

REVoLUTTON AND THE

coMMoN MAN

2

94. North China Herald,5oo.

95. I draw heavily on a long description by Lim Boon-keng (Lin \Tenqing)

published in th.e North China Herald, z4 February r9r2, 5oo-r. See also

Minlibao, 16 February t9r2, r; Shengiing shibao,3 March rgr2, 4. For the

texts

of the addresses

The Republican Citizen

see Sun Zhongshan, Sun Zhongshan quanji

(Complete works of Sun Yatsen; Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, r98z) vol. z,

94-7.

When SunYatsen formally adopted the solar calendar in January rgrz

it was an action that had the potential to affect the daily lives of the

entire population. Over the years the Republic came to affect not oniy

people's perception of time, but also the clothes they wore, the way they

and stood. From being conlreeted friends, even the way they moved

these were soon being inof

revolution

moment

of

the

choices

scious

processes of learning

mundane

the

schoolchildren.Through

culcated in

a set of dispoacquired

individual

life

the

how to behave in every-day

In the

natural.

seem

sitions which made certain actions and responses

new dispositions of the Republic the new Republican ideology was

embodied, turned into 'a durable way of standing, speaking, walking

and thereby of feeling and thinking'.l Children and adults learned to

bow rather than kowtow, then to walk, stand and sit in ways that

expressed their new role as Republican citizens.

A

Fashion

for Republicanism

During the spring and summet of tgtz a wave of enthusiasm for the

symbols of the Republic swept the country. JinWenzhen, a woman from

Anhui, recalls in her memoirs the curious features of the wedding organized for her student husband that year. For the central ceremony of

the wedding he wore a Western-style suit and she a costume designed

on the pattern of the court dresses of the ancient Han dynasty. The

kowtow was omitted in favour of a tWestern-style bow This dramatically

modern wedding was held in the rather conservative town ofWuhu, a

place where most people were still wearing Qing dynasty costumes for

weddings until well into the r93os.' Nevertheless in rgrz the Westernstyle costume and etiquette reflected genuinely popular fashions.

The main elements of this fashion were Western-style suits for men

and$Testern-style hats worn with these suits but also with a long gown.

Costumes worn in late Qing China had varied according to the gender,

class, official status, ethnicity and location of the wearer as well as the

time of year.The following description simplifies greatly in order to give

the reader some idea of where the new styles fitted in to this great variety

of costume. Most Han Chinese men and women wore loose trousers,

with a loose jacket over the top.The fabric depended both on the season

50

THE REPUBLICAN CITIZEN

and on what the wearer could afford, with most people wearing light

cotton garments in the summer and thick padded ones for northern

winters, while the rich wore silk. \X/omen's clothes differed from men's

in the greater length of the jacket; in addition married women of the

wealthier classes might wear a long pleated skirt. Elite men whose occupations did not demand strenuous physical activity wore full-length

loose gowns and on informal occasions a short 'riding jacket' (magua)

over the gown. This ensemble was often topped by an embroidered silk

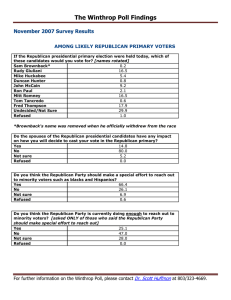

skullcap (Fig. ). Officials on formal occasions wore an additional

embroidered robe and an official hat. Both robe and hat varied with the

status of the official concerned.3 Hardly surprisingly, formal official

robes, embroidered as they were with the symbols of the empire, were

considered inappropriate for the new republic.a \Testern-sryle costumes

replaced official robes for the inaugurations of LiYuanhong, SunYarsen

cllAl'. U. DE8

Srtf,UTA?loNs.

Ftc. 4. Qing dynasty

etiquette and costume.

Chinese-style bow

(yr). The men wear formal

official dress and hats.

Belozr: Clasping the hands

(gong shou).The men wear

gown, riding iacket and

A b oa e:

skull cap

Soarce: Simon Kiong,

"Quelques mots sur la politesse

Chinoise " Variiti s Sinologique s

z5 (t9o6), p. 5 (Bodleian

Pl.

llL-Tso.i

et Koug-chcou

Library, University of Oxford

Chin.d.73.)

THE REPUBLICAN CITIZEN

5I

andYuan Shikai. Moreover in tgrzWestern-style clothes were also used

for private occasions: Jin$Tenzhen's husband was married in a suit. An

old man commenting on the revolution in a county town in Zhejiang

remarked sarcastically that all the men had cut their queues overnight

and the young men had all boughtWestern-style suits which made them

look like a Pack of monkeYs.5

Western-style suits marked the wearer as a reformer or a'new person',

but they were far too expensive an investment for most people.6 Instead,

men associated themselves with the new policies by buying\Western-style

hats to go with their newly shorn hair. The Qing dynasty skullcap and

the various shapes of official hats were suddenly replaced with \Testernstyle felt hats, cloth caps and straw boaters. A diarist in Shanxi notes in

r9r3 that unlike the practice in earlier years his New Year guests no

tonger wear formal dress, and that some even wear foreign hats't The

new hats were worn, as the old had been, primarily with a long gown'

The craze was thus limited for the most part to the elite who were the

wearers of gowns. Nevertheless one newspaper commented that even

those who had trouble affording food were laying aside their old straw

hats and buying new ones; the reporter noted cynically how much more

eager people were to buy imported straw boaters than government

bonds.s'Westerners meanwhile were lamenting their failure to profit

from this valuable new trade which had been cornered by Japan.e In

Zhejiang a modern-minded member of a major lineage announced

before the regular lineage sacrifices that since the Qing had fallen participants should not wear red hats or long gowns and jackets, and provided those who had cut their queues with modern hats.r0

With these fashion items went a new etiquette' Men wearing the new

soft felt fedoras or stiffer bowler hats raised them in greeting, as was

customary among European and American men at the time. Letters

indicate the popularity of this gesture by using it as a closing phrase.

Thus a letter from a local government trainee to PresidentYuan Shikai

written in July rgrz ends with the writer's declaring that he 'takes off

his hat and stands straight'.rr Similarly a rgr3letter-writing manual suggests ending a letter with 'Your younger brother so-and-so takes off his

hat'.r2 For a more formal greeting a man held his hat in his hand and

his arms by his sides and bowed stiffly from the waist (Fig. 5). A Shanghai man's friends presenting him with a congratulatory statement on

his sixtieth birthday in r9r3 sign off 'together bow and respectfully give

their best wishes'.13 This bow (jugong, hereafter ''Western-style bow')

was the one used at Jin Wenzhen's modern wedding. A cartoonist who

wishes to satirize the new republicans for adopting only the outward

forms of the Republic shows two Chinese men in \Testern dress per-

Y

IHE REPUBLICAN CITIZEN

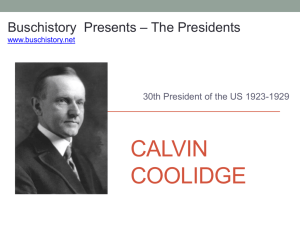

FIc. 5. TheWestern-style bow

(Jugong). An illustration from a

primary school textbook shows

school boys and their teachers

bowing to the Five Colour

National Flag at the start of the

school term

THE REPUBLICAN CITIZEN

53

':.:J

tgi

't+'

S,,zrcc: Zhuang Shi. Shen Qi, Liu

Ru, Xb{a guoyu jiaoheshu (New

method national language textbook;

Shanghai: Shangwu yinshuguan,

rgzz), vol. 3. p. r.

Frc. 7. Qing dynasty edquette

from a village manual. These

different forms of kowtow each

express precise degrees

difference of status

of

Source: [Village manual] (Historical

Literature of Sha Tin vol. 5; Hong

On To Memorial Collection, Hong

Kong University Library)

Ftc.6. The

appearance is

correct but the spirit is far off

Soarce: Frcdcrick McCormick,

facrng p. 442^

forming the etiquette of the Qing (Fig. 6): one clasps his hands to his

chest while the other removes his glasses, both gestures associated with

Qing ritual greeting. The cartoon is labelled, 'The appearance is correct

but the spirit is far off'.ra

Men acting according to the etiquette that was customary during the

Qing might have performed a bow, but in this Chinese-style bow (yi)

the arms were not kept at the sides; instead, as can be seen from Figure

4, the clasped hands fell with the motion of the body. Moreover this

Chinese bow was not, as in contemporary \Western etiquette, the only

common formal gesture of greeting available to men.t5 It was one of a

series of gestures that expressed the relative social or official positions

of the participants (Fig.7).This series stretched from a clasping of the

hands (gong shou), used to greet equals on informal occasions' to the

complex movements of the kowtow performed to the emperor which

involved standing, kneeling and touching one's head to the ground eight

times. A more common form of the kowtow used for superior offlcials,

teachers, parents or at weddings involved kneeling down and touching

the head to the ground four times. Women performed kowtows but not

the Chinese-style bow which was replaced if necessary by a slight inclination with the hands clasped at the waist (lianren).16 The new Westernstyle bo% however, was seen as being equally appropriate for women

54

THE REPUBLICAN

THE REPUBLICAN CITIZEN

and men, except that since women did not wear hats they were not

expected to doff them.

What were the causes of the sudden enthusiasm for a set of 'Republican' customs that seem to us so decidedly \il(/estern? For some years

before the revolution'Western-style customs had been associated with

revolutionaries. During the late Qing students who continued to wear

\Testern clothes after returning to China did so not for aesthetic or practical reasons but because of what the clothes represented. European

clothes of this period were stiff, tight and generally uncomfortable.

Men's suits made of woollen cloth were expensive, not easily obtainable and unsuitable for hot climates.rT In the r93os LinYutang wrote

an article on 'The inhumanity of \Western dress', specifically men's

dress, which was by that time if anything slightly more comfortable than

it had been in the r9oos. He attacks it as a 'system of suffocating collars,

vests, belts, braces and garters' and goes on to say)

The prestige of foreign dress rests on no more secure basis than the fact that

it is associated with superior gunboats and Diesel engines . . . Its superiority is

simply and purely political.t8

If this was true in the r93os when Western styles were commonplace,

it was far more true in the r9oos.'Western dress was adopted because

of what it represented. It is likely that many elements of this fashion

were in fact observed in and imported from Japan, which was accessible to far more Chinese than either Europe or America, and which had

itself adopted many 'Western styles from short hair and felt hats to

'Western-style uniforms from the r86os onwards.re However Western

styles were seldom perceived as Japanese: it was the power of Europe

and America that gave the new styles their prestige.

The primary values that\Western dress and etiquette were seen as representing were liberty and equality" Taken from European and American understandings of republicanism these had been the rallying cry of

the revolutionaries in the r9oos. After r9r2 they were constantly emphasized in intellectual discussions as the foundations of the new state.

The ideas were also repeated in school textbooks. It was clear that Qing

dynasty etiquette, with its careful differentiation of rank and status

which we have already seen in gestures of greeting, was not really compatible with the idea of equality.20 Many of the semi-mythical stories of

the early days of the Republic depict it as a moment when the old

inequality between officials and people was changed. Thus the story is

told of Sun Yatsen raising to his feet a man who had come to see him

and explaining that in a republic one need not kowtow to the president.2l Mythical though the story may be, it reflects a reality which is

also expressed

in the preamble

CITIZEN

55

to Yuan Shikai's laws on the etiquette

in the

for m""tittg. This states that the etiquette for meeting laid down

status or age.

ancient texts differentiates between individuals of different

the old etiequality

and

freedom

on

new

emphasis

the

since

Th"t"fot"

In

this case

is

needed.22

one

a

new

and

be

abandoned

had

to

lu"*" has

point

same

greeting,

but

the

gestures

of

to

th" u.gn-.nt was applied

used

also

was

which

costume

Was sometimes made when discussing

Hats,\WesternJ.rring the Qing to express official rank and seniority.z3

and

sryle suits for official occasions, taking off one's hat to one's friends

people

of

the

minds

in

the

president

were

all

symbolic

the

to

bowing

who used them of the equality of citizens under the Republic.

Of course once the revolutionaries were in power identification with

them was also in itself advantageous. As a contemporary newspaper

suggested, many of the leading figures in the new Republic had lived

abroad and thus become accustomed to straw boaters, leather shoes

and woollen clothes. According to this account the people most keen

to use foreign goods were people involved in the government who hoped

in this way to be associated with the new policies. Ordinary people then

copied the trend-setting politicians.2a This public link between the revolution and foreign influence was of course unacceptable to some revolutionaries: Zhang Binglin, who was both a leading radical and a

renowned classical scholar, published an essay which located the origins

of the new etiquette (raising the hat and bowing) in the customs of the

Han d1masty.25

Changes in costume and etiquette were also expressions of fashion in

a highly fashion-conscious society. The old image of an unchanging 'traditional China', combined with the tendency of recent historians to

emphasize slow structural changes in society, makes it hard to imagine

late Qing China as a society where rapidly changing fashions played an

important part in people's everyday lives, but it seems that such was the

case.This was not, as has been suggested, a Republican development.26

Local historian Liu \ffenbing, looking back on his Shanxi county of

Xugou in the r93os, remembered the women's hair styles of his childhood:'cart wheels' and'fan style'in the r86os, then in the r87os a single

coil at the back of the neck which gradually increased in size and by r894

covered the top of the head. Liu also discusses changes in the cut and

style of men's outer garments from the same period." Centres of fashion

in the rgoos were Beijing, Guangzhou and Suzhou/Hangzhou.28 A

description of Chengdu in r9o9 points out that fashions in men's hats

change every year in line with changes in Beijing, while women's clothes

change each year following the fashions set by popular actors.'e In his

memoirs JiangYi, who was brought up in Jiujiang in Jiangxi, describes

56

THE REPUBLICAN CITIZEN

THE REPUBLICAN

his mother objecting ro the nurse plaiting his hair in an old-fashioned

way, and instead insisting on doing it herself. Fashions in clothes and

hairstyles reached Jiujiang, a major porr on the yangzi, from Beijing,

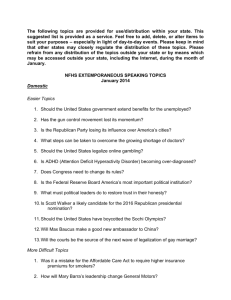

Shanghai and Nanjing. JiangYi's drawing (Fig. 8) depicts some of the

various hairstyles fashionable in Jiujiang in his childhood. For special

occasions professional hairdressers came to the house to do the women's

hair in the latest style.3o Poor women too might cut their hair to create

a fashionable fringe round the face.3r Fashions changed fastest among

the rich, but fashion was not the sole prerogative of the rich. A writer

describing changing fashions among the differenr classes of people in

the inland cities of Xi'an and Lanzhou notes that middle-class women

are slow to adopt new fashions because they associate the very idea of

fashion with the rich or prostitutes. But the result of this is not that their

clothes do not change, simply that they change long after the fashions

in Beijing. Thus around ryr4 middle-class women were following the

Beijing fashion in ceasing ro wear very tightly cut clorhes but they had

taken instead to the extravagantly wide-cut jackets which had gone out

of fashion in Beijing in the r9oos. For both middle-class and lower-class

women in Xi'an and Lanzhou doing the hair in a round bun, long out

of fashion in Beijing, was the newest rrend.32 By r9r4 it was said that

fashions spreading by this time from Shanghai moved so fasr that within

two years from its initiation a fashion would have reached Sichuan and

something new would have been adopted in shanghai.33 Fashion then

was both rapidly changing and pervasive. New fashions spreading from

a few major east coast cities affected hairstyles, headgear and the cut of

ru

CITIZEN

57

rich

darrnents. Change was fastest and most dramatic among the urban

fashionable

the

as

general

such

styles,

but

3i ,n" fashion-setting cities

and high collars of the early I9oos, reached even to lower-class

,infr,

*or.n"",in the distant cities of the north-west.

By the time that the inauguration of the Republic brought full

been

Vestern dress into fashion for men, \(/estern styles had already

advertising calAn

time.

for

some

fashions

Chinese

existing

influencing

been popular

endar for r9r4 shows the main features of a style that had

cut

tight,

close-fitting

and

collar

(Fig.

The

high

9).

since the early rgoos

At

the

r9oos.

and

r89os

of

the

are both reminiscent of Western styles

colours

the

bright

from

sarne dme men's long gowns had moved away

and embroidered surfaces of the mid nineteenth century to simpler,

darker colours.3aTheWestern costumes of the Republic should thus be

growing

seen as part of a larger fashion forrJfestern styles that had been

which

revolution

rgrr

the

by

transformed

was

but

rgoos,

since the

power'

political

to

styles

proponents

ofVestern

brought the

ww

\

$

W

w

W

Frc. 9. Women's fashion

seen

W W

FIc. 8. Fashions in

women's hairstyles in

Jiujiang as recollected by

w

JiangYi

Sozrce: ChiangYee,

8"9

C hildhoo

d

r94o), p.

(Ilndon:

53.

A

Chinese

Methuen,

as

in an advertising

calendar poster for the

Xiehe Trading Company

Soarce: Claire Roberts, Ezolation and Reaolution: Chinese

Dress tToos-r9gos (Sydney: Powerhouse Publishine, r99l), p.

zo. Reproduced courtesy of the

Powerhouse Museum, Sydney,

Australia.

58

THE REPUBLICAN CITIZEN

THE REPUBLICAN CITIZEN

It was during the period when \Western costume and etiquette were

the heights of fashion that the new Republic wrote its laws on customs"

It was assumed, as it turned out incorrectly, that the full \iTestern

costume worn by elite fashion leaders at the time would soon spread to

the general population. As was the case with the calendar, it had been

customary for dynasties to promulgate new regulations for officiai

costume and etiquette when they took office. In August rgrz the government published a law on etiquette. According to this law standard

etiquette for men was to raise the hat and bow. For everyday meetings

this was to be reduced to the simple raising of the hat, while for celebrations, sacrifices, weddings and funerals men were to bow three times.

$fomen were to follow the same rules, except that the raising of the hat

was replaced by a single bowr5 That this law was following rather than

leading the fashion is illustrated by its similarity to a slightly earlier ser

of rituals for civil officials in Sichuan, which also prescribed raising the

hat and bowing, with a triple bow ro show particular respecr.36 Shortly

after issuing the law on etiquette the government also issued laws on

formal dress. Two levels of formal dress were specified: full formar, for

major state occasions, and regular formal, for other official events (Fig.

l0). Full formal consisted of the costumes then known in English as

morning dress and evening dress. Regular formal dress was divided into

two types" The first type copied \Western dress of the day with either a

bowler or a felt hat. The second type was a long gown, riding jacket and

bowler hat. officials were not supposed ro wear this latter garb for the

performance of their official duties. w'omen's dress followed the formal

dress of wealthy Han Chinese women during the eing with a long

pleated skirt worn beneath an embroidered silk jacket.37 As was the case

for the law on etiquette the law on costume reflects widespread notions

about proper official dress for the Republic. Thus in cili, a small rown

in Hunan, Republican officials in tgtz wore cosrumes entirely in the

'European' style, with felt hats, leather shoes and woollen jackets.3s

The extent to which the choice of costume was motivated by considerations of fashion and symbolism is indicated by the fact that this

was done despite considerable opposition from the silk industry. yuan

Shikai proposed that full formal dress should copy the United Srates

even as representatives of the silk industry protested to the government

at the choice.3e Western-style formal dress was made of woollen cloth,

which China did not produce, and was therefore entirely imported.

Thus, not only the new laws but also the widespread fashion for

\Western-style clothes was seen as a serious threat to the silk industry.

In response to this threat the Chinese National Products promotion

Association sent representatives to Beijing to request that the new law

59

ffi

Regular formal Tlpe A

Evening dress Morning dress

Full formal

Evening

dress Morning dress

::

.':

rVomen's formal

Frc. ro. Formal dress

as specified

c

dress

Regular formal Tlpe B

by law in rgrz

Source'. Da zougtotrg gottgbu catryqruan yijue Zhortghua

Miryuo;fualri ru (Pictures of the dress system for the

Republic of China decreed by the House of Representatives and promulgated by the President; Guohuo

weichihui, rgrz). Courtesy of the No. z Archives, Nanjing, Chrna.

6o

THE REPUBLICAN

THE REPUBLICAN CITIZEN

specify that any formal dress be made of Chinese fabric. The request

was granted. However, since China did not at this time manufacture

any woollen cloth and $Testern-style dress could not in fact be made

from silk this part of the law was simply not obeyed.ao

But then nor was much of the rest of the law. The full \Westernstyle costumes of rgrz never did spread to the general population,

perhaps because of their discomfort, inconvenience or expense, perhaps

because they conflicted too much with existing ideas of proper dress.

Full \ilestern formal dress never became more than a fashion for the

political elite, and like other elite fashions it passed. As the fashion

passed, the laws of tgtz came to enshrine an outdated vision of the

Republic. Proposals made in the rgzos for a new national costume

comment on the popularity of the \Western-style morning and evening

dress in r9rz, but say that a year later it was hardly ever used. By the

r92os not one in a hundred officials owned this full formal dress, while

scarcely one in thirty had the \Western suit and bowler hat decreed

for official regular formal dress.nt These costumes were confined to diagrams in textbooks or on the walls of schools. Instead, ignoring rules

to the contrary, officials wore gown, jacket and bowler hat. Similarly the

bow prescribed by the new etiquette was felt to be insufficiently respectful in many sistuations.a' A conservative scholar, Wang Kaiyun, who

atttended a funeral in r9r4 along with seventy members of the National

Assembly, noted that only two or three of those present restricted their

respects to the three bows prescribed by law.a3 Children continued to

kowtow to their parents, students to Confucius and devotees to deities.aa

Perhaps most telling of all is the case of Cheng Renlan, the daughter

of Jin Wenzhen, the Anhui woman whose modern rgrz wedding

was described earlier. Whereas Jin \Wenzhen had bowed rather than

kowtowed at her wedding in accordance with the fashion of the day,

Cheng Renlan faced the opposition of her in-laws and husband

when she wished to bow rather than kowtow at her wedding in the

r93os.nt

Republican Citizens

To say that the Republican symbols of rgrz were part of a fashion and

that that fashion passed is not to say that the symbols were no longer

relevantl Cheng Renlan, when I spoke to her in her r98os, counted her

refusal to kowtow at her wedding among the more important events in

her life. Rather it is to suggest that the new symbols came to have a different sort of meaning in the years that followed. Instead of marking

the transition between new and old, Republic and Qing, these symbols

CITIZEN

6T

to mark members of a group who defined themselves as Repubcitizens'

fican

Studies of etiquette in European societies have shown that manners

oneself within a parcan work as a means of orienting and integrating

partly

result

of a link comas

a

functions

This

ticular community.46

and outer

morals

inner

between

rnonly drawn within such a community

traChinese

classical

conduct. Such a link was of course central to the

well

as

dition of 'ritual' (/i ), which included manners and costume as

the performance of ceremonies and was seen as the outer expression of

the inner virtue of humanity. Chow Kai-wing argues that during the

maior approach to

Qing dynasty scholars came to stress ritual as the

one of the most

thus

became

ritual

and

that

order,

ethics and social

car1re

competed for control of public

symbols.a? Access to this tradition of ritual was through the classical

texts and therefore required considerable education. In this way education provided status both in the access it gave, through the examination system, to official positions, and by teaching the student, through

ritual, manners and costume, to present himself as a member of an

elite.a8 With the abolition of the examination system and the adoption

of a system of 'modern'Western-style academies, the classical education began to be replaced as a marker of status by the presentation of

personal modernity.The new costume, manners and customs all played

a part in presenting oneself as a modern person. These elements thus

became the means through which individuals laid claim to personal

important ways

in which groups

status.

Like the classics, the symbols of modernity were taught in schools.

This was in part a product of expectations, derived from the examination system, that education would confer status) combined with the type

of modern education that children in fact received. As well as memorizing information about the world around them, children learnt what

was expected of a modern Chinese citizen. Some of this was conveyed

by direct instruction. The first lesson of a primary school ethics textbook shows the pupils bowing to the teacher (Fig. l l). The pupils have

taken off their hats while the teacher wears a \Western-style suit. School

termr according to the textbooks, begins with an opening ceremony in

which the teacher and pupils gather in the school hall and bow to the

nadonal flag and then to each other (Fig. 5). Pupils were also instructed

on how to bow to the national flag with texts for young children showing

the correct posture and giving instructions: 'first bow, second bow, third

bow' (Fig. 11). In other lessons the teacher was told by the textbook to

tell pupils to wear a hat outdoors and not indoors, and to raise the hat

when meeting someone as a sign of respect.ae That modern manners

THE REPUBLICAN

CITIZEN

63

primary school teaching is suggested by

to shake hands as

r9z7-50 In addiin

in

Nanjing

primary

greeting

school

at

of

I L.r,rt"

primary

school texttexts

of

and

illustrations

the

teaching

tion to direct

a chapter

proper

behaviour.Thus

for

pupils

norms

with

books presented

guests,

in

a gown

one

two

shows

guest

home

in one's

on how to greet a

lWestern-style

hats

felt

their

with

suit, seated

and jacket, the other in a

(Fig.

hanging on pegs on rhe wall while the good pupil offers them tea

l1). Illustrations depicting pupils coming to school show boys and girls

in trousers and jackets, with the boys in military-style caps; parents wear

long gowns, jackets and fedora hats (Fig. 11)' By conveying norms of

costume and etiquette schools created a consciousness of symbols of

modernity shared between pupils and teachers.

These norms were new and different from what most pupils would

have been used to at home, where patterns of behaviour were set by

members of an older generation. One account of the$(/estern-style bow

claims that it only happens in schools and government institutions and

among people with very modern ideas, since many individuals still

think that it is not respectful enough.5r Similarly an account of the adoption ofWestern-style dress notes that people wore Western-style clothes

for particular occasions: calling on superior officials, or entering a

government building.52 In the domestic environment, for New Year,

weddings and funerals, most people continued to perform the various

forms of the kowtow. Thus the writer Xiao Qian, who grew up in

Beijing, recalls that as a child he kowtowed to older family members on

his birthday, but bowed to the tablet of Confucius at school.53 This difference between domestic and public behaviour worked to emphasize

the association between the modern behaviour and the Republican

indeed conveyed through

were

'a

rnafl who explained to me that he had been taught

Pupils bow to the teacher

"The teacher and the students pay their

respects to the national flag. First bow,

second bow, third bow"

state.

By observing certain rules of costume and etiquette individuals could

present themselves as members of a modern community and also identify other members. In his novel of life in a small town school the author

Ye Shengtao notes the way in which introductions and greetings during

this period gave the potential for instant assessments of modernity.

"Invite the guests in to sit in the room. I

stand by the table and offer tea to show

respect to the guests-"

Pupils arriving at school

Ftc. rr. Illustrations from primary school textbooks

&rurces: ShenYi, Dai Kedun ed., Gonghe guomiu jiattheshu xitt xiusheu (Republican citizens'textbooks New

Ethics; Shanghai: Shangwu yinshuguan, 1922 (rst edition rglz) vol. r. p. 3; Zhuang Shi, Shen Qi, Liu Ru,

vol. z. p. t-z; ZhuangYw, ShenYi Gongheguo jiaokeshu xitr guowen (Republican series textbooks New

Nlcti^--l

D--i-...

f

Qh^--L-:I.

eL^*-.,..

..:-^L..-.^-

,.r:-:^-

,,^l

h

/r.

n^--w/^-

When Ni Huanzhi, the enthusiastic, modern-minded young schoolteacher, is introduced to his new colleagues, the Chinese language

teacher removes his spectacles and nods (the same gesture satirized as

old-fashioned in Figure 6), while the Japanese-educated teacher of

physical education makes a deep bow 'as if he were giving the students

a demonstration in the drill ground'.54 The moment of introduction is

described in detail as it is through these gestures of greeting that the

characters first reveal to each other their attitude to modern ideas and

64

THE REPUBLICAN

THE REPUBLICAN CITIZEN

institutions, and thus at the same time the degree to which they participate in the community of modern citizens.The handshake is perhaps

the ultimate example of the sense of community conveyed by the new

etiquette. Before the introduction of \ilestern customs the handshake

was a gesture of intimacy. A good feeling for this is given by Rong Qing,

a conservative and elderly Mongol, who noted in his diary for r913 that

on seeing an old friend he 'grasped his hand in joy'.55 Taking the

meaning of the gesture from a very different tradition, a school textbook published in r9r4 instructs pupils to shake hands when they

welcome a guest, since this is the proper behaviour for a citizen.56 The

way in which these elements combined to create a sense of camaraderie

among the young and modern-educated is suggested in Ye Shengtao's

novel when Ni Huanzhi greets a modern-minded friend by shaking his

hand.57 Shaking hands marked both men as members of a single community which had adopted foreign customs, while at the same time creating a bond of intimacy between them.

'We

should note, however, that the handshake (unlike the bow) was

not universal among all those who aspired to present themselves as

citizens of the new state. It was, and remains, a problematic gesture for

women. The handshake marked an inner community of advanced

modern citizens. The same sense of communities within communities

becomes apparent when we look at attitudes to male dress. One account

of dress written in the early rgzos claims that one can categorize people

according to the style of their clothes. The author distinguishes two

types of modernizing male dress, the 'organization style' and the

'student style'. Those who wear the 'organization style' are members of

the new groups and associations formed in the rgoos, politicians,

officials and gentrymen. They wear either a'Western-style suit or a long

gown and riding jacket. By the rgzos neither of these items of clothing

was particularly fashionable but these men wear old-fashioned clothes

partly because they are old and partly because their positions of authority require them to look old. The 'student style' by contrast consists of

'Western-style

uniforms, leather shoes and Western-style hats. Although

these men wear gowns they do not wear the riding jacket.58 The existence, and popularity, of both the jacket, gown and felt hat, and the

'student style' suggests two things. First, jacket, gown and felt hat

became the costume of Republican citizens (and thus officials) in the

early years of the Republic. Secondly, there was a group of people within

that larger group of Republican citizens who had marked themselves

off as radicals by wearing a more'Western style of dress. As was the case

with etiquette, Republican forms defined a communiry that was itself

divided.

CITIZEN

65

But if the community was divided so were individuals. The language

which individuals could

of Republican symbolism was a means by

at different times.

communities

different

within

th"*selves

I.-ocate

up in Beijing in the

brought

family

Mongol

a

wealthy

from

girl

ifr.r, "

,oro, t"*.mbers being taught by her parents to perform different

for different occasions. For visitors who were from conserva"l"etines

iiu. fu-ifi.t she learned to perform the conventional Chinese style of

wornen's greeting with hands clasped at the waist, and for more

greetings for Mongol and

rnodern people a bow. She also learnt special

Beijing during the late

in

official

as

an

Similarly,

guests.5e

Manchu

to

the\Western-style bow

accustomed

was

Bai

diarist

Jianwu

19ros, the

in r9r9 he returned

Yet

when

gesture

respect.

of

as the predominant

to his family

he

accommodated

funeral,

home for his grandfather's

of days later

A

couple

enough to spend the day kneeling and kowrowing.

he complains in his diary of how his legs ache from this unaccustomed

exercise.6o

Individuals then adopted modern customs to identify themselves with

specific communities; but most individuals were active in a variety of

communities, each of which called for different adaptations and variations. The layering of customs and identities which this produced is

perhaps best seen in people's use of the solar calendar during this

period. In February rgrz Yuan Shikai's Beijing government confirmed

Sun Yatsen's adoption of the solar calendar as the natural accompaniment to the Republican system of government.6r The authorized cal-

endar issued

by the government included the lengths of

days,

predictions for eclipses and comets with scientific diagrams and explanations. It did not include the lunar dates and or any information connected to the customs associated with the lunar calendar. This was

naturally inconvenient in a society accustomed to the lunar calendar. A

government memo which accompanied the compilation of an officially

authorized joint solar and lunar calendar for r9r5 claimed that the

simple solar calendar was too inconvenient for ordinary people who

held to the old customs, so there was no alternative to the use of the

old calendar, and that in these circumstances it was not unnatural that

privately published almanacs abounded.62 Since the government had

lost the monopoly that the Qing dynasty had to some extent maintained

over the production of almanacs, private publishers suited everyone's

convenience by providing almanacs which listed lunar equivalents of the

solar dates and other useful information.63 Interestingly it seems to have

been common for privately published almanacs illegally to claim official

authorization.6a Forced to compete with these privately published

almanacs local governments compromised and issued calendars

66

THE REPUBLICAN

THE REPUBLICAN CITIZEN

illustrated with the symbols of the new government but showing both

lunar and solar dates. One issued in Shaoxing had the president's portrait and the new national flag printed on the front page; another issued

in Chengdu showed crossed flags and an emblem with the anniversary

of the independence of Sichuan. The Shaoxing calendar included the

dates of anniversaries of the revolutionary government and days of the

week, but excluded information about auspicious and inauspicious days

and the birthdays of the gods.65 In r9r4 the central government realized the impossibility of its campaign to make everyone use only the

solar calendar and itself issued a calendar that included both solar and

lunar dates.66

As the publication of calendars with only solar dates suggests, it had

at first been assumed that all dates would immediately be fixed by the

solar calendar. Thus salaries would now be paid according to the solar

months, and it was hoped that the business community would adopt a

quarterly system for the settlement of debts, instead of the old system

which required debts to be settled at New Year, the Dragon Boat Festival and the Mid-Autumn Festival. Where this was implemented it

would force people to be aware of the solar dates, and part of the rhythrn

of the year would fall into line with the government's new calendar.

Exhortations to merchants to use the solar calendar were frequent.

These came from the government and occasionally from local chambers of commerce. In Hangzhou the city's chamber of commerce held

a debate on whether or not to convert to the solar calendar. The two

sides of the argument put forward were that as citizens it was the duty

of the members of the chamber to respect the government's decision,

but that the traditions of business practice especially concerning the settlement of debts, made this very difficult for them.67

Evidence of compliance with these exhortations tends to be limited

to announcements that from now on the solar calendar will be used by

a specific group or for a specific purpose. Thus in January rgr2 the

Shanghai naval command announced that it would begin to distribute

rations according to the solar month.68 In February Suzhou pawnshops

and Shanghai banks switched to the use of solar dates.6e In Changchun

in March the local authorities ordered the use of the solar calendar for

paying debts and for paying government employees; but in Fengtian,

while government servants were to be paid by the solar calendar, military rations would still be issued according to the lunar months.T In

April a date was set on which Shanghai bankers would switch to the

solar calendar.Tr Banks, it seems, possibly because of hear,lt foreign

involvement in the industry, did switch to the solar calendar, but as late

as 1927 petitions were still requesting the government to enforce the

CITIZEN

67

of the solar calendar for monthly receipts and the annual clearance

old calendar attitude was

Jf debts.t, As one novelist commented,'That

society'.71

hearts

of

in

the

settled

,riU nt-ty

In this situation many individuals used both calendars. As one author

the citizens of a repubof a leaflet promoting the solar calendar noted,

[c should not be divided, but

rrs€

Calendar are both used, some

Now because the National Calendar and the Old

others take the old calendar

and

standard,

calendar

as

oeople take the solar

people

want

to use both the National

who

are

also

some

There

as standard.

NewYear twice.Ta

celebrate

the

and

who

Old

Calendar

the

and

balendar

This is not iust polemic: diary entries inform us that a great many

people did indeed celebrate the NewYear twice, once on the solar and

Ltr." ott the lunar date. At first this appears puzzling and self-contradictory, but if we consider the calendar as a series of layers by which

individuals marked their membership of particular communities it

begins to make sense.

When Sun Yatsen, Yuan Shikai and others encouraged the adoption

of the solar calendar in China they saw the calendar in use in Europe

and America as a single unified whole. However a recent study of the

English calendar in the early modern period suggests that it can more

helpfully be seen as a series of layers: the natural cycle of the seasons,

the agrarian calendar, the Christian calendar, a scatter of saints' days,

the legal calendar, civic calendar and a cycle of recent political and religious anniversaries.T5 An examination of the calendar as it was lived in

Republican China suggests a similar series of layers.

In his account of life in rural Shanxi, diarist Liu Dapeng records the

holidays and festivals celebrated in his village. Basic to this village calendar is the cycle of the lunar year with its three main holidays-the

NewYear, the Dragon Boat Festival and the Mid-Autumn Festival-as

well as minor holidays such as the Zhongyuan Festival, when sacrifices

were made to ancestors, and Double Ninth when many people climbed

hills. This lunar calendar was particularly closely tied to business and

trade since the three major holidays were also the settlement dates for

all debts. Intertwined with this lunar calendar was the ancient solar calendar with which farmers marked the seasons of the agricultural year.

According to this calendar the year was divided into twenty-four solar

periods. Some of these marked important festivals such as the annual

holiday for grave sweeping, Qingming, and. the\Winter Solstice, while all

were the occasion for specific agricultural activities. In addition to these

the village had a series of local holidays relating to the worship of local

deities, with occasions such as the Birth of Lu Dongbin (one of the

68

THE REPUBLICAN CITIZEN

Eight Immortals who was born in Shanxi) and the \Welcoming of the

Holy Mother (the goddess who conrrolled the local irrigation sysrem)

being major annual evenrs in village life. Finallg individuals kept personal anniversaries, especially their own birthdays and the anniversaries

of the births and deaths of their parents. Thus the year as it was experienced was formed of the interaction of each of these calendars, and

when during the Republic the solar NewYear and National Day began

to be celebrated they were integrated as part of a new cycle of holidays

related not to religion, agriculture or trade, but to the Republic.T6

As an inhabitant of a rural village Liu Dapeng kept and noted an

intricate calendar of religious and agricultural festivals. However, an

examination of the rather fewer holidays noted by urban diarisrs suggests the same layering of solar and lunar calendars. Bai Jianwu, a diarist

living in Beijing, regularly notes the three major festivals of the lunar

year (|.Iew Year, Dragon Boat Festival and Mid-Autumn Festival) and

sometimes also the Double Ninth Holiday. The activities he takes part

in on these occasions are urban and secular: he visits parks, goes out of

the city to walk in the hills, goes to the theatre and dines well. Moreover, the emphasis is not on community activities but on his family and

friends; these are days when he feels homesick and his friends visit him.

In addition Bai Jianwu notes the major holidays of the new Republican

year, the solar NewYear and National Day. Sometimes on these holidays he took part in activities thar were specifically related to the Republican state, as for example on r January rg2o when he joined other

officials to take part in a formal visit to the governor's offices. on other

occasions he celebrated the new holidays in ways very similar to the old:

a visit to a park or a walk in the hills outside the city.77 Even where a

diarist did not take part in formal activities he might be moved to

certain emotions or resolutions by particular dates. Thus Hu Jingyi,

another North china diarist, uses both the winter Solstice and the solar

New Year to reflect on recent events.ts While use of the ancient solar

agricultural calendar marked membership of the farming community,

and celebration of the major holidays of the lunar year was especially

appropriate for the business community, celebration of the new national

holidays, especially the solar NewYear and National Day, marked one's

membership of a community of Republican citizens. An individual kept

the holidays of several of these calendars as he or she marked his or her

membership of a variety of communities.

Constant debate on the use of the new solar calendar made many

individuals aware of the political implications of their choices. Thus in

r919 Hu Jingyi opts to write his personal diary according to the solar

calendar because the use of the solar calendar is required by 1aw.7e

THE REPUBLICAN

CITIZEN

69

at the same time, a much less debated drift towards the use

the week marked the spreading influence of the structure of the solar

lives.The division of time into a sevencalendar in individuals'personal

is a feature of Christianity. As a

on

Sunday

a

rest

day

with

day week

have been familiar both to

it

would

custom

American

and

European

to those who had contact

and

abroad

spent

time

had

Chinese who

government

announcement

to

a

According

with foreigners in China.

r9rz.80 Before

in

by

schools

irrrrdryt were already commonly observed

the introduction of Sundays local cycles of work and rest revolved

around periodic markets and fairs. A village school whose holidays were

recorded around I93o gave the pupils, in addition to the New Year

holiday and breaks for the spring and autumn harvests, eleven days'

holiday each year, arranged to enable them to go to the different fairs

in the area. This was the sort of schedule that would have been common

to many schools before the introduction of the solar calendar, but the

addition had been made that Sundays were used to review lessons.8l

Schools were not the only institutions to adopt the use of the week. Bai

Jianwu and Wu Yu, another diarist this time in Sichuan, both mention

Sundays as features of their working timetable'82 Bai Jianwu went

beyond this to organize his personal life around the newly imported

week by deciding to have a bath twice a week.83

As was the case with costume and gestures, people were willing and

in some cases eager to adopt elements of the solar calendar to mark

their membership of the new national community. This national community was one among many that any given individual belonged to, and

although a few radicals might suggest that it should replace all other

communities and identities, the majority of people were deeply concerned to continue the customs and practices that marked those other

communities. The new customs then created the Republican citizen as

one among a number of identities available to the people of China, while

many other identities remained in popular use.

Nevertheless the Western-style customs that marked the Republican

citizen did also mark a group within society. Those within the group

flowever,

-of

continued to be aware of commitments to other communities and of

alternative layers of identity but outsiders, whether traditionally minded

Chinese or $(Iesterners, perceived the group as a clearly defined community and dismissed alternative layers of identity as hypocrisy. In r9r3

Liu Dapeng, who still identified personally with the Qing dynasty and

was thus very much an outsider) commented that since the'rebellion'

all the members of the 'new party' had 'completely taken on the outer

appearance of the foreign barbarians' by adopting a foreign system of

government, the solar calendar and foreign costume.8n Liu divides those

70

THE REPUBLICAN CITIZEN

he comes across into 'the people' (min) who keep to the old ways, and

a group variously described as 'the new party', 'those who have rebellious hearts' and 'men in office', who celebrate the festivals of the solar

calendar and adopt other markers of Republican identity. On one occasion he comments that when officials celebrate the solar New Year the

people look at them and say, 'That is their year, not our year'.85 A

Western journalist trying to describe the same phenomenon in Sichuan

in the r92os wrote,

Since rgrr the new official has had two things, namely, a new hat and a new

coat, and these gave him a new conception of life, which in turn has slowly

produced what we are trying to describe as a new Society.s6

According to this author the idea of 'society' is a relatively new concept in Sichuan. It is always a minority, and in this case a minority

composed mainly of educated young men who are interested in national

affairs. In order to enter 'society' the young men 'assume a distinctive style of dress, usually a soft felt hat and a large foreign-cut overcoat. The wearer of these things in one step enters Society.'S? Although,

as this journalist points out, 'society', the community of Republican

citizens, was almost always a minority, it envisaged itself as the

whole nation. Therefore texts written by insiders seldom admit to the

degree to which this was in fact a relatively exclusive group. From

this point of view travel accounts are interesting since they can

provide an indication of the kind of people with whom the author

identified.

One of the most fascinating accounts of this kind is the diary of Ou

Zhenhua, a Cantonese man who travelled on foot through the country

as an officer in the Nationalist Party's Northern Expedition. The diary

intersperses military data with sympathetic accounts of the people he

met and what they told him of local customs. On reading the diary it

soon becomes apparent that, while Ou Zhenhua was personally sympathetic to almost everyone he met, he identified two types of people

and places, describing one as 'open minded' (kaitong) and the other as

'not open minded'. The latter are marked by the men's queues, the

bound feet of the women and the wearing of long gowns and riding

jackets. But they are also identified by their lack of knowledge of or

interest in 'the country'. Thus having spent the day marching through

part of Shandong he commented that,

The people along the route were none of them open minded. They did not

know what sort of thing a 'country' was, and they had not cut their queues,

were illiterate, lived in cramped houses and paid no attention to hygiene.s8

THE REPUBLICAN

CITIZEN

7T

In a town in northern Jiangsu he noted that the people were not very

open minded, in that when he was reading or writing official documents

they stared at the floor and did not know what to do with themselves,

and when he spoke of national or party affairs they did not know what

the country or the party was.8e In Liyang county in the south of Jiangsu,

by contrast, he comments that the people were very open minded and

rnany women had cut off their hair.eo The sense in which these distinctions underscore a feeling of community is suggested by his account of

leaving Liyang. When he came to take leave of the county magistrate

Ou Zhenhua was going to shake hands but the magistrate immediately

clasped his hands together and performed a deep Chinese-style bow.el

The image is a vivid one. The two men had got on well together and

both the Chinese-style bow and the handshake carried with them the

symbolism of equality and friendship. The failure of the two men to

come together in their gestures of friendship is a poignant example of

the exclusivity of the new national community and the gestures and

customs that marked it.

Gender and CitizenshiP

To what extent were women part of this new community of Republican citizens? Jin $(renzhen's bowing at her wedding and Ou Zhenhua's

mention of the short hair of the women of Liyang both suggest that

some of the symbols of citizenship were available to women. This was

very different from their role in the Qing when they were by definition

excluded, not necessarily from political activity, but from the symbols

that legitimated it. The Dowager Empress Cixi was a powerful force in

the high politics of the state, but she received guests sitting behind a

screen. Below the monarchy the symbols of legitimate power were

monopolized by the civil service) a career not open to women. Women

could, and sometimes like the Dowager Empress did, play an active role

in politics; but in doing so they were going against the norms of both

state and society. However, when in r9r2 the empire became a republic, the very idea of citizenship was a new one. From a stratum of male

officials dominating a homogenous mass of 'people', society was to

become a collection of individual citizens. As a concept citizenship was

still ill-defined.. \Women did not receive the right to vore for the various

provincial and national assemblies. Nevertheless that women were not

by definition excluded is suggested by the occasional incidents of

cutting of women's hair and those women's meerings that took place

during the course of the revolution. That women were not immediately

excluded was the consequence in part of the new ideology and in part

72

THE REPUBLICAN

THE REPUBLICAN CITIZEN

of social changes that affected women during the late Qing. In particular

while the education of women was not new, girls' schools introduced

by Western missionaries had created a class of women accustomed to

participating in public institutions. F{owever, although the ideology of

the new Republic left space for women as citizens, citizenship was experienced by men and women in different ways"

One of the reasons that citizenship was experienced differently was

that some of its symbols were different for men and women. \fomen

were told to express their citizenship and their affiliation with the

Republic by unbinding their feet and by allowing their daughters to

grow up with natural feet. From the earliest revolutionary announcements in Wuchang, just a few days after the revolution, women were

told to unbind their feet in the same sentence as men were told to cut

their queues.n'An order forbidding foot-binding issued by the government of Zhejiang province in rgtz condemns the practice as having

harmed the country over the centuries more than anything else. First,

as was common at the time, the announcement assumes that the weakness of women crippled by bound feet would be passed on to their

children. The custom of binding women's feet is thus described as a

direct cause of the military weakness of the nation.e3 Ideas of inherited

physique and genetics, and with them an emphasis on the importance

of strong healthy mothers, had become popular in China during the last

years of the Qing, so this part of the announcement reflected the

received opinions of the day.ea Secondly, and this is a much more radical

statement, the Zhejiang order condemns the binding of women's feet

on the grounds that

because [their] feet are bound their movements are unsteady, so they live

indoors and seldom go out, they do not receive education and know little of

the outside world, they cannot make an independent living or collectively contribute to the wider world.qs

This statement links the unbinding of feet to the presentation of women

not only as the mothers of citizens but as citizens themselves who should

be educated and understand world affairs. Through these arguments

natural feet for women) which had begun to be a reform issue largely

as a result of missionary influence during the last years of the Qing, was

tied in to the new Republican order.

One of the means by which natural feet were linked to the Republic

was the pairing of bound feet with the queue. Campaigns against bound

feet in the rgros and rgzos almost always included an element directed

against the men still wearing queues. In Shanxi,Yan Xishan declared a

carrtpaign against

opim smoking.e6

CITIZEN

73

bad customs, by banning bound feet, queues and

A folk song collected there in the r96os recalls how

for five or six years,

Now the Republic has been around

down

two commissioners.

has

sent

capital

The provincial

queues,

wear

their

people

not

to

One tells

One tells people not to bind their feet.

They post up a notice in the street.e?

This pairing of bound feet and queues soon became widespread and

the two were much used as a metaphor for backwardness. So for

example, a traveller in Gansu criticized the local government for

not instructing the people to cut their queues and unbind their feet.e8

Similarly Ou Zhenhua, describing the Zhili countryside) wrote'

since I entered Zhili province, despite marching back and forth along the roads

for hundreds of miles, I have not seen a single woman with natural feet and

half the men have not yet cut their hair.ee

Short hair and natural feet were seen as the outward signs of compliance with the Republic. One man writes in his memoirs of how, when

his family in conservative Shanxi came to include three men without

queues and four women who had unbound their feet, the whole family

was labelled 'new people' (xinren) by the neighbours.l00

The linking of natural feet and short hair as markers of Republican

identity for male and female respectively created the illusion that the

symbolic issues involved were similar. This was not initially the case.

The queue was) as we have seen, originally a Manchu custom, imposed

on Chinese men as a mark of submission to the Qing dynasty. The

binding of women's feet, by contrast, was a custom that originated

among the Han people. It has even been suggested that it evolved partly

as a way of defining the Chinese against the nomadic peoples of the

Central Asian steppes of whom the Manchus were one.tot Although it

appears that many Manchu women subsequently accepted the aesthetic

appeal of small feet and designed special platform shoes to imitate the

practice, Manchu women's natural feet were an important part of what

defined them as Manchu. In one part of Shanxi the term Manchu actually referred specifically to the natural-footed servant girls of wealthy

families.102 Moreover the Qing had on several occasions issued edicts

banning foot binding by Han Chinese women as well as the Manchus.r03

Thus, whereas queue cutting originated in both anti-Manchu sentiment

and \Testernization, in allowing their daughters to have natural feet

THE REPUBLICAN CITIZEN

THE REPUBLICAN CITIZEN

families of the late Qing and early Republic were influenced primarily

to

confined

-On

marriage women then put their hair up, and with this it became far

u"".ptable for them to be seen on the streets and in public. So

74

by ideas ofwesternization conveyed as modernization. However, the frequent repetition of the link between the cutting of queues and the

unbinding of feet meant that this was not always how the issues were

perceived. one man reminiscing about how the women in his

family

unbound their feet claims that although the binding of women,s feet

was not a Manchu custom) the Manchus had encouraged the Han

to

do this in order ro weaken them.r.a Although the memoirs were written

in the r98os this idea with its curious mixrure of genetics and antiManchu feeling is characeristic of the early Republican period.

The issue of bound feet and queues reveals how citizenship was eNperienced differently by men and women because the symbols

of citizenship were different. However, in the case of other symbols which

were open to both men and women the experience of citizenship was

also differenr because what went before had been different. So, for

example, the fashion for short hair for women which began in the late

rgros appeared to draw parallels with the queue cutting movement.The

author Ding Ling cur her hair short at school during the May Fourth

movement. when she went home her uncle snorted in disapproval,

'Humph! You really do like to have fun.you've had so much fun you,ve

lost your tail'' Ding Ling repried to this criticism by berating her aunt

for her bound feet and comparing her own action with the revolutionary cutting of men's queues: 'Didn't you have some fun losing your tail

some time ago? If you could cut your hair then, why can,t I cut my

hair

now?'r05 A second wave of hair cutting for women was associated

with

the Nationalist revolutionary movement of the mid-r9zos. The essayist

Zhou zuoren commented in t9z6 on the way in which newspaper

reports of women who cut their hair described them as female revolutionaries. Looking back to the late eing he recalled how any man who

cut his queue was described as a revolutionary, and noticed ihat people

were now doing the same to women who cut their hair. zhou Zuoren

questions whether the cutting of women's hair can really be compared

to the queue cutting of the late eing, since unlike rhe men,s queue, the

women's long plait was not in any way a Manchu symbol.106

But this was not the only reason that short hair for women was not

quite equivalent to the cutting of men's queues. perhaps more important was the fact that for many girls it was not cutting off their hair but

putting it up that symbolized their entrance inro the modern world of

the Republican citizen. It was common practice for all children to have

the head partly shaved and to wear their hair in two or more short plaits.

At about the age of thirteen girls began to grow their hair and wear it

in a single long plait, and it was at this age that girls began to be strictly

75

the family home in preparation for betrothal and marriage.

n,or.

many girls putting

while cuttittg the hair might be revolutionary, for

of a new freedom of

their hair up like a married woman was a symbol

participate

in

affairs outside the

to

a

freedom

so

of

and

rnovement

part

uniform of most

of

the

was

thus

in

a

bun

hair

the

Wearing

horne.

r9r9, with the

home

durin9

from

girl

ran

away

who

One

schoolgirls.

first

action

was

to change

how

her

recalls

help of a radical magazine,

jacket

short

into

the

black

from her conventional trousers and long

jacket and skirt which were the customary dress of women students.

When she did this she felt like'a soldier putting on his uniform hastily

before going into battle'. Next a friend helped her to unplait her hair

and put it up into a bun which'symbolized my struggle against the convenrions'.r07\(lhile Ding Ling and radicals like her might attempt to use

exactly the same symbols as men to mark themselves as citizens, for

many girls entry into the group of Republican citizens was a gendered

experience.

Girls who came to identi& themselves as citizens of the Republic and

who entered the male world of political affairs experienced changes

similar to those their brothers experienced as they grew up and entered

the adult male world. Like their brothers, many girls now moved from

a confined domestic space to the public spaces of streets and parks,

schools and institutions. One man writing his memoirs remembers as

one of the features of the rgrr revolution that after this time women

could enter government offices, and that therefore the headmistress of

the local girls' school would visit the county magistrate's offices.t08 On

the level of high politics, a former minister in the Beijing government

records how his wife came with him to attend a formal banquet held

by the government to welcome Sun Yatsen to Beijing in rgrz.roe In

domestic spaces people still kept to the lunar calendar, kowtowed to

relatives and deities, and, for the most part, wore trousers and long

jackets. In the public world men and women marked themselves as

citizens of the Republic by using the solar calendar, bowing in the

S7estern style and adopting new styles of clothing.

However, whereas for men these changes which marked a new elite

developed out of earlier systems for marking status) for women the

new symbols had the effect of inverting earlier marks of status. In

Qing China women were central to a family's presentation of its status.

Families that could afford to do so attempted to conform to the ancient

ideals expressed in the classics.These stated that after childhood women

should remain in the inner part of the house, meeting only the menfolk

76

THE REPUBLICAN CITIZEN

THE REPUBLICAN CITIZEN

of their own family and having no contact with the outer, public

girls who received an educaschool students were girls, indicating that

world.lro Bound feet, though the custom had not been adopted until

the Song dynasty and was thus not mentioned in the classics, were a

symbol of this way of life since they made it difficult for women physically to move beyond the domestic environment. The restrictive ideals

have subsequently, as Dorothy Ko has pointed out, often been related

as if they were the realities of women's situation in late imperial

China.rrr In fact, at least in the last years of the Qing, the ability and

desire to comply with these norms was related to the wealth, background, ethnicity and even the religion of individual families. In

Chengdu in r9o9 lower-class women commonly worked as wet nurses

and domestic servants, as well as earning money by mending clothes,

collecting firewood, peddling ornaments, telling fortunes and pulling

teeth.1r2 A wealthy woman who visited Hong Kong at about this time

was surprised not that there were women in the streets but that they

were women of good family; in her home town only servants and

working women walked freely in the streets.rt3 And while some daughters of working households who were destined from childhood to a life

of physical labour might escape having their feet bound altogether,

others would sleep with the bandages off after a hard day's work, rhus

allowing their feet slowly to spread.lra As in the contemporary West,

while many women did engage in strenuous physical activity such activity was not seen as feminine.rr5The ideal of a narrowly restricted domestic life was stringently enforced only on young women of marriageable

age and the wives and daughters of the elite.

\We have seen how the new Republican customs such as the hat, the

bow and the solar calendar marked a national community, and thus

were a means of displaying personal status.\Women, like men, learnt the

new customs and behaviour by attending modern schools. Indeed one

author complained that often this was all they learned:

Usually in other places one sees a lot of schoolgirls who haven't yet learnt anything much, but who wear clothes and carry things that are different from most

people. They get to such a pitch that when they see other people they look

down on them. This is called learning to be a schoolgirl, it is not girls going to

schoollrr6

That women were slower than men to adopt the new Republican

customs was partly because girls were much less likely to receive a

modern education. In r916 only 4 per cent of pupils in non-missionary

schools were girls. As late as rg32 only 15 per cent of primary school

children were girls. However at the same time 18 per cent of secondary

77

tion *"t" disproportionately likely to come from families wealthy

years of modern eduction.rrT

,norrgtr to support them through several

were

the prerogative mainly of

women

for

of

citizenship

symbols

The

the symbols of citizenand

consequently

group

women

of

this small

their

ship came to be markers of the elite status of those women and

families.

Many of the customs that were symbols of the new citizenship and

thus of elite status were precisely the opposite of earlier markers of elite

sutus for women. So, for example' previously women's bound feet had

been symbols of the family's ability to raise its daughters without the

necessity for hard physical labour.r18 Now natural feet came to be signs,

not of the labouring classes, but of those who could afford to send their

daughters to modern schools.The same inversion of the former symbols

of status can be seen in the use of space and in clothing. Upper-class

women were now able to move freely in public spaces which had formerly been the prerogative of working-class women and servants.When

the Ritual Bureau ofYuan Shikai's government fixed the government

prescriptions for etiquette, it explained the inclusion of rules on bowing

for women by saying that in ancient times women and men were strictly

confined to their separate roles' and women did not go out of doors or

have any contact with men. But now, the bureau explains, all that has

changed: girls'schools are being established everylvhere, and women go

out to study and to see friends so they need to have some kind of etiquette prescribed for meeting.ttn Other sources reveal that whereas previously girls were told that it was the mark of a lady not to let any part

of her body except for her head and hands be seen, now schoolgirls

wore calf-length skirts and jackets with wide elbow-length sleeves.r'o

One upper-class girl who visited an amusement park in Tianjin and saw

fashionable girls wearing skirts, short jackets and ribbons on their plaits,

was told by her mother, 'No girl of good family would go about dressed

like that'.12r For the mother the immodesty of the girls'dress was a mark

of low status; for the daughter, who sees her mother as old-fashioned,

a short jacket, skirt and leather shoes was precisely the costume that

marked its wearers as members of the national community.

By influencing and changing the norms which had been used to

define elite sratus, the new ideal of citizenship came to affect the whole

definition of femininity, and thus the construction of gender. In the past

the delicacy and weakness of women had been defining characteristics.

Generations of young men sighed over such weak and sickly heroines

as Lin Daiyu in the Dream of the Red Chamber. Bound feet both empha-

78

THE REPUBLICAN CITIZEN

THE REPUBLICAN CITIZEN

sized and induced this kind of weakness. Women with bound feet found

standing for any period of time painful; their most characteristic posture

was sitting.t" When they did walk they swayed slightly. An American

girl who was brought up by missionary parents in Shandong in the late

nineteenth century writes in her memoirs about watching a Chinese

girl, whose feet had not been bound because ofher parents'connection

with the church, practising walking:

She tried to walk as those who had bound feet walked, to walk as a woman

should walk. . . She could not mince and make her body sway as the bound

footed women minced and swayed.r23