Gender & History ISSN 0953–5233

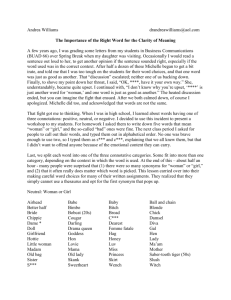

advertisement