GLOBAL COLOURS: Theories, Materials and Colouring Agents in Global History

advertisement

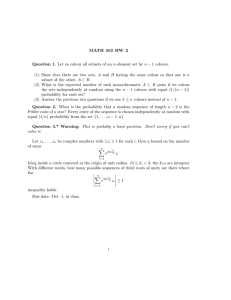

GLOBAL COLOURS: Theories, Materials and Colouring Agents in Global History Friday 27 April 2012 Ramphal Building, R0.14 Programme 12.00-13.00 Lunch 13.00-13.45 Paul Smith (University of Warwick) “Colour and Language: Neither Nature Nor Nurture” 13.45-14.30 Pippa Lacey (University of East Anglia) “Imperial Red: The Uses of Red Coral, Shanhu, at the Imperial Qing Court in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries” 14.30-15.15 Ghulam A. Nadri (Georgia State University and LSE) “India and the Development of the World Indigo Market in the Seventeenth and Early Eighteenth Centuries” 15.15-15.45 Coffee break 15.45-16.30 Hanna Hodacs (University of Warwick) “Colours in abundance and bundles – the sale of Chinese silk textiles at the Swedish East India Company’s auctions” 16.30-17.15 Anne Gerritsen (University of Warwick) “Alabaster and Sapphires:’ Seeing Porcelain and Knowing China in Early Modern Europe” 17.15-17.45 Final Discussion The event will be followed by a reception and dinner Abstracts Paul Smith (University of Warwick: Paul.G.Smith@warwick.ac.uk) “Colour and Language: Neither Nature Nor Nurture” In 1969, Berlin and Kay advanced the argument that human colour perception, being grounded in innate perceptual capacities, has a universal structure that can be discerned in the sequence in which any language adds colour terms to its lexicon. This offered a viable alternative to the hitherto dominant thesis of Sapir and Whorf, which contended that the different languages each impose their own particular structure on colour perception. Advocates of nativism and relativism have since advanced increasingly sophisticated, but no less divergent, variants of these foundational positions, with only a very few scholars even attempting to find common ground between them. The aim of this paper is to look how at the recent research perpetuates this impasse, and to offer a way out of it based on Wittgenstein’s ideas about the ‘language-games’ we employ when using colours in particular situations. Pippa Lacey (University of East Anglia: Pippa.Lacey@uea.ac.uk) “Imperial Red: The Uses of Red Coral, Shanhu, at the Imperial Qing Court in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries” Red coral, corallium rubrum, was employed as an expression of self-representation, cultural identity and political life at the Qing Chinese imperial court during the seventeenth and eighteenth century. Material and colour hierarchies played a central role in the ordering of the Qing universe. As ‘son of heaven’, the Qing emperor was the centre around which the Chinese empire was ordered and arranged. This paper examines the variety of uses and diverse meanings and significance of red coral, shanhu, at the Qing imperial centre. It builds an understanding of red coral through an investigation of material culture and literary sources. Ghulam A. Nadri (Georgia State University and London School of Economics: gnadri@gsu.edu) “India and the Development of the World Indigo Market in the Seventeenth and Early Eighteenth Centuries” India was a major producer of commercial indigo and a supplier to Euro-Asian markets before the blue dye began to be produced in Europe’s trans-Atlantic colonies. In the first half of the seventeenth century, Indian indigo dominated the European markets replacing, almost completely, the dye produced in Europe from woad. While the European East India Companies trading in India exported large quantities of indigo to Europe, the Europeans, including the companies, were also exploring alternative sources of supplies. Exploiting land and labour potentialities, the European settlers and planters in South and Central America succeeded in producing indigo on a large scale to cater to the European demand. The Dutch East India Company in Asia, too, left no stone unturned to find a Southeast Asian alternative to Indian and American indigo for European dyers. In this presentation, I will examine the causes of this quest for alternative sources of indigo and analyse its implications for the indigo industry in India and for the world indigo market in the early modern period. Hanna Hodacs (University of Warwick: h.hodacs@warwick.ac.uk) “Colours in abundance and bundles – the sale of Chinese silk textiles at the Swedish East India Company’s auctions” In this paper I will discuss Chinese silk textiles (e.g. Damask, Taffeta and Paduasoy) for sale at the Scandinavian East India Company’s auctions (from 1730s and onwards). I will primarily discuss the textiles imported by Danish and the Swedish companies but I will also include some comparisons with the other European companies' assortments. I will particularly focus on the descriptions and references to colours in some of the remaining sales catalogues: What can we learn from the names of colours used here? Did names/references vary between different companies? Did the differentiation of colours increase over time, or did some colours disappear while others were added? I will also discuss the compilation of colours in different lots/bundles of textile for sale: What was the relation between the variations of colours in a lot for sale and the price it caught? One overall ambition with the paper is to illuminate the role of the Scandinavian companies in providing consumer at home and (maybe largely) in other European countries with silk textiles: Can an approach focusing on colours help understand the European market for Chinese silk and the existence of national variations? The paper is a result of research conducted within the ERC project 'Europe’s Asian Centuries: Trading Eurasia 1600-1830', based at the University of Warwick. Anne Gerritsen (University of Warwick: a.t.gerritsen@warwick.ac.uk) “Alabaster and Sapphires:’ Seeing Porcelain and Knowing China in Early Modern Europe” This paper seeks to explore early modern globalization from the perspective of material culture. It does this by looking at the ways in which European understandings of colour were shaped by the influx of porcelains from China and Japan. Brightly coloured porcelains had started to arrive in Europe in large quantities from the late sixteenth century onwards, and their materials, shapes, and designs were highly evocative to early modern Europeans. Yet we know very little about the reception of their colour. One of the innovations of the porcelain production in China was the use of cobalt to create decorations. In a European environment where colour was often muted, the influx of blue-and-white porcelain must have been striking. I explore here what European observers of China knew about colours and pigments, and how that knowledge changed during this time of growing exposure to Chinese and Japanese porcelains in China and Japan.