Talk London 29 ground floor, 5.30

advertisement

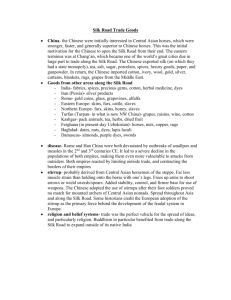

Talk London 29th Trading and Consuming: East India Companies and Europe (G35), Senate House, ground floor, 5.30 Maxine has already given you the broad background to our project, it is about placing the Eurasian trade within the context of the consumer revolution in early modern Europe, and ultimately understanding its role in shaping European manufacturing producing goods which could compete with the Asian imports. This of course does not mean that all European East India Companies operated under identical or even similar conditions. And in this talk I will focus almost exclusively on the Danish and particularly on the Swedish company. Since I assume that these two companies are rather unknown I have summarised their 17th and 18th century histories on the first page of the hand-out. NEW SLIDE Now, the Dutch, the British and to a certain extent the French Companies had strong domestic markets ready to consume the Asian ware. They also had access to the Atlantic world to which goods could be re-exported. In the Scandinavian countries and particularly Sweden, the situation looked somewhat different. There was little demand for exotic goods from the East in the poor hinterlands of Gothenburg and Copenhagen. Instead most of the goods imported by the Swedish East India Company (SOIC) and Danish “Asian Company“ (DAC) was re-exported (between 70% and 90%). NEW SLIDE This circumstance forms the starting point for my work, which is that a study of the Scandinavian companies is particularly well suited to illuminate the pan-European market for East Indian goods and the role of Gothenburg and Copenhagen as peripheral emporiums supplying this market. By using Pan-European and periphery as starting points a set of new questions are generated, such as: How were quality demands and fashionable trends negotiated not only with distant producers but also in relation to distant consumers? What role did the annual and sometimes biannual auctions in Copenhagen and Gothenburg play as events where goods were launched and prices set for a larger Continental market? Who bought the goods and what role did the whole sellers have refining goods and promoting product development? In my work I will focus particularly on the trade in Chinese tea and Chinese silk. And before I discuss some aspect of this work I would like to underline that this is work in progress. NEW SLIDE Why these two types of goods? Chinese tea was the engine in the Scandinavian trade with Asia, both for the Danish company, which also traded with India, and the Swedish which traded with China almost exclusively. It was not however tea consumers at home that the Scandinavian companies were trading on behalf off. The general assumption is that the great bulk of the tea brought to Europe by the Continental companies, and not at least the Scandinavian, ended up as contraband in Britain. It was the high duties on tea in Britain that created circumstances which made smuggling so rife. When with the Commutation act of 1784, tea duties in Britain was brought down from a 119 to 12.5% the underlying rational for the Scandinavian companies cease to exist. Of course the Scandinavian companies were not the only ones providing the British market with tea. The monopoly of the EIC was undermined by French and Dutch tea as well. One aspect I am currently working in on is how the Scandinavian companies competed with the others in terms of buying and selling tea focusing particularly on how qualities were understood and how that influenced the trade. The success of the Scandinavian Companies depended on the ability of their staff to buy good quality tea of popular sorts, particularly of cheapest types, Bohea Tea and Conguo. This was then sold off with the help of whole sellers in Amsterdam and Rotterdam, people like Pye & Cruishank, John Forbes and George Clifford and Sons, who also traded with Dutch and French imported tea. In fact it seems to largely have been Dutch tea whole sellers, that defined which teas qualities were most suitable for the British market. Although the single most important goods, in terms of quantity and value, the Chinese tea did not travel by itself to Europe. The composition of cargoes from China reflected both the need to balance the bulky but relatively light tea with heavier goods and with consumer demands in Europe. Chinese porcelain functioned as a counter weight to the tea. Moreover, the porcelain was scent free, and could hence not pollute the tea. Stored in the bottom of the ship it also protected the tea from dampness. Silk was third most important goods in terms of bulk that was brought from China. Relative to its weight it was by far the most valuable. What makes tea and porcelain import different to the silk is that the former goods were much more exclusive to China (European porcelain production dates back to the 1710s, but China only lost its monopoly over tea production in the beginning of the 19th century). Silk textiles, of course a goods which originating from China, had in contrast been produced in Europe since the 11th century. By the 18th century European silk production and consumption was a very dynamic sector. Governed by annually changing fashions, London, Paris and Lyon formed the central nodes in the European manufacturing of silk textiles. It was particularly French silk manufacturers that lead the way, regular changes of styles, patterns and colour schemes helped them stay ahead of the competition. The significance of France is also reflected in the migration of workers, many silk industries such as for example the Stockholm one, was largely made up of skilled silk workers from France. Competitors outside France used samples from Lyon as blue prints. The time delay in producing replicates of the French stuff meant that that French manufacturers could stay abreast. Consumers in Europe paid according to their means and eagerness to display the latest, or very latest trends. How did Chinese silk faired on this very competitive European market? The fact is we do not really now. For several different reasons. First of all, it is notoriously hard to identify where a piece of silk is made by examining it. Silk was produced across the Eurasian continent, from China, to India, Turkey to the Mediterranean world and northern Europe in the 18th century. As with the porcelains there was a cross fertilisation of styles and patterns between Asia and Europe. Here are two examples which I got from Martin Cizuck in Sweden, which he assured me were made from Chinese 18th century Silk, not unlikely to have been imported by the Swedish East India Company. NEW SLIDE NEW SLIDE Moreover, many European countries banned the import of Chinese silk for domestic consumption, in order to protect its own silk manufacturing industries. This was the case in Britain, the silk imported by the English East India Company could only be re-exported. In Sweden a series of bans limited the import of silk textiles for domestic use from the late 1740s and onwards. We can therefore assume that a lot of Chinese silk, like the tea was smuggled. Smuggled goods are of course notoriously hard to follow, it does not leave much documentation in its wake. Some of the movement of Chinese silk imported by the Swedish East India Company is however possible to trace in what, within the context of the study of East India companies, is a pretty unique type of source material, namely a series of annotated sales catalogues covering 17 out of the first 26 years of the companies existence. Next to listing the material for sale at different auctions in Gothenburg between 1733 and 1760 the catalogues also contains hand written notes of the prices and the names of the purchasers. NEW SLIDE This is a page in the 1748 catalogue covering the sale of the cargo of two of three ships that arrived that year from Canton. As you might be able to guess what is listed as for sale was 4310 Poises Dammask. These damask pieces was sold in 143 lots, containing on average 30 pieces per lot. Each such lot, was made up by different coloured pieces. The proportions of different coloured silk pieces varied. The first 50 lots had the same variation, or assortment of 15 colours, which included 4 Crimson, 4 Sky blue, 3 Green, 3 Jonquil, 2 Ash coloured, 2 Mazarin Blue etc. What first draw my attention to this part of the sales catalogue when I saw it was the terminology for specifying the colours. I had just been going over some ordering lists sent out to India by the English East India Company and compared to the descriptions of goods London wanted its factories in India to purchase colours seems to matter much more in the Chinese case. This obviously have to do with the fact that Indian cottons came painted and printed in elaborated patterns, colours seems to be secondary to these patterns. But even so, the colour of the grounds of the India chintz and Calicoes are referred as simple blue, black and red. In the case of the Chinese Silk however, there are for example a great variety of shades of blue such as Dark Blue, Middle Blue, Light Blue, Mazarine Blue, Milan Blue, Mourant Blue, Sky Blue, and Turquin Blue. On the hand out I have listed the names for colours used describing assortments of Poises Dammask in the catalogues from the period between 1733 to 1753. The reason why they are listed in three languages are because the sales catalogues were printed both in German and Swedish. The English translation is inspired by the colour terminology of the English East India Company, used in the ordering list sent to China, and other material, generated by English speaking supercargoes working for the Swedish Company. Silk is a fibre that absorbes dyes like maybe no other. In studying the nomenclature of the colours I found that many of the colour terms used have a long history for describing particularly silk clothes in Europe. But we can also trace a global history of colours in the names. Take the colour Karmine or Crimson in English, it was generally a colour produced with a dye made from an insect with the scientific name Kermococcus vermilis planchon. It had been used for producing red dyes including for textiles on the whole of the Eurasia continent, since the prehistoric period, including China.1 The dye was called Kermes and many European and Asian languages have a name for red which is derived from the word kermes, including here Karmine and Crimson. Generally though, the colour nomenclature used to describe the Chinese silk has a distinct French emphasis. One assumes this nomenclature was quite different from the colour terminology used in China. I have not yet been able to find a way to compare the nomenclature of colours used to describe Chinese silk in Europe with existing Chinese terms but this is something I want to pursue in the future. In a translation of Sung Ying-hsing The Creation of Nature and Man, from 1637, which describes among other thing dying techniques we find terms such as Lotus Pink, Peach Blossom Pink, Earth Brown, Tea Brown, Grape Blue, Peacock- and Sky blue.2 In Chinese material Paul van Dyke has used, illuminating the smuggling of silk textiles dyed in colours exclusive to the Chinese court (such as yellow and red) the term Tea coloured is used, which might refer to yellow. With the exception of Sky Blue I have found no references to these colours in ordering lists and sales catalogues of the European East India Companies. This suggest that, in contrast to the Chinese names for the qualities of tea the nomenclature used to define the Chinese silk textiles were largely Franco-European one, which the supercargoes from the different companies used jointly. It is also likely that negotiations with the Chinese merchants was conducted with the help of sample books. What we know is that the Silk orders were one of the first to be settled as the European ship arrived. The Chinese merchants were usually given 3 months to deliver ordere goods. Enough about the nomenclature of colours. Is there any other way we can use the colours listed in the sales catalogue in order to understand how the role of Chinese silk on the European market? One aspect I am currently working on is how much the composition of colours changed over time in the silk imported from China by SOIK and DAC. Such a study would give me some indication of how the demand for Chinese silk changed in response to market changes in Europe. Now of course there was a limit to how quick the East India Companies could respond to changing fashions in Europe. The return trip between Europe and China took a good 18 months in the 18th century, the annual changes in terms of fashionable colour schemes could not be copied in China. This however does not mean that other slightly slower trend changes were ignored n the trade with Chinese silk. 1 Although could also be producd by Safflower cakes boiled in smoked Chinese plumbs, The Creation of Nature and Man (T’ien-Kung K’Ai-Wu), 1637 by Sung Ying-hsing (in Chinese Technology in the 17th century, 1967) 2 In order to make valid comparisons over time I have taken the quality Poises Dammask, which was the quality of which the SOIK imported the largest quantity. It is also the quality which came in one of the widest range of colours. NEW SLIDE I have recorded 18615 pieces being imported during the first 9 years of which I have sales catalogues (1733 to 1753). If you add the colour of all these pieces together into one diagram you get this. And here I have been trying to match the colours of the different segments with the colour they refer to. As you can see the most frequent colours were Crimson Red, White, Sky Blue, Jonquil Yellow. NEW SLIDE Another way to present it is in this way. NEW SLIDE If we take the most frequent colours and focus on what happened over time, it is possible to detect changes. The proportions of Sky blue and Crimson, the two most common colours in which Poises Dammask came, changed quite dramatically, as this graph illustrates. Almost 20% of all the pieces in the first lot were Sky Blue, while only 3 % were Crimson. The next records from 1742 show that they were almost the same amount Sky Blue and Crimson pieces. In 1745 the number of Crimson coloured pieces surpasses the number of Sky blue, the roles are reversed in 1748. What happens then though is surprising, Crimson coloured pieces seems to establish a permanent lead while Sky blue almost disappears. This does not mean that Blue poises damask pieces ceased to be imported from China to Sweden between 1749 and 1752. Instead what happened in 1748 was the introduction of new shade of blue, Bluemourant, which refers to a Light shade of blue I think. As this graph suggest the Bluemourant shade replaced Sky Blue as the leading blue colour. NEW SLIDE Such developments suggests maybe that rather than a change of colours, maybe what we see here is a change in terminology. What colour a name referred in the 18th century is of course hard to say, since few sample books containing Chinese silks remains. In fact, 18th century Europe saw several projects headed by scholars interested in physics, chemistry and natural history as well as trades men involved in the dyeing industry, trying to establish systems for pinning names to shades of colours. The growing impact of fashion did however work in an opposite direction. One force destabilising the nomenclature for colours were the reintroduction of old dyes with new names. Now, is this what we can see taking place in the case of Sky blue, is Blumeurant just another name for sky blue? Hard to tell but my guess is not in this case, there are 14 lots of Poises Dammask sold in 1742, which contains both types of blue which suggest they were two colours which could be separated. In other cases it is harder to establish if we are talking about one shade and two names or two names and two shades. The term Dark Blue and Mazarine Blue seems for to have been used as synonyms, at least up until 1751. NEW SLIDE One more graphs before I stop. This graph describing the frequency of lemon yellow and straw coloured silk pieces suggest that these colours were demanded at the same time. Being two lighter shades of yellow it might reflect the dynamic demand for this type of yellow in Europe. How to sum things up then, well one conclusion is that in spite of the possibility of different names being used for the same shade of for example blue the statistical series I have been able to produce so far indicate that the what was brought home by the Swedish East India Company reflected changing demands in Europe. Such a thesis can also be supported by correspondence between supercargoes working for the Swedish East India Company and whole sellers of Chinese goods on the continent. The latter, several of which were, also engaged in the whole sale of tea, advised the supercargoes on what colours were the most popular in the Dutch Republic, and consequently what to buy for their pacotille in terms of silk textiles in different shades. NEW SLIDE This brings me back to the relation between tea and silk and the end of the paper. The silk cargo of the two ships Cronprintzen and Calmar, on sale in Gothenburg in 1748, were bought by 44 different merchants. If we match it with the 31 different merchants who bought tea at the same auction we find 18 merchants purchasing both tea and silk. This together with the evidence of continental whole sellers influencing the purchasing of privately traded silk goods on the Swedish ships suggest that at least some of the silk and the tea from China continued to travel together, not only to Gothenburg but onwards to continental markets in the Dutch Republic and beyond. Colours of pieces of Poises Damask imported by the Swedish East I India Company 1733+1753 Black Blue Blue, Dark Blue, Light Blue, Mazarine Blue, Middle Blue, Millan (?) Blue, Mourant Blue, Sky Blue, Turquin Brown Brown, various Brown. Cinnamon Gray Gray, Ash Gray, Lead Green Green, Celadon Green, Dark Green, Grass Green, Light Green, Lime Pearl Pink, Rose Purple Red, Cherry Red, Crimson Red, Incarnat Red, Poppy Red, Scarlet Silver Straw White Yellow Yellow, Jonquil Yellow, Lemon Schwartz Blau Dunckelblau Hellblau Bleumorant Himmelblau Turquinblau Braun Braun, divers. Canelfarbe Aschgrau Celadon Dunckelgrun Hellgrun Perlfarbe Coul. De Rose Kirschenfarbe Carmoisin Scharl.farbe Paille Weiss Gelbe Jonquille Citrongelbe Swarta Mörkblå/Märkblätt Liusblå Mazarinblå Middleblätt Millanblått Blomerant/Bleumeranta Himmelsblå Turqvinblått Brunt Grå Askfärgad / Askgrätt Blyfärg Gröna Mörkgröna Gråsgröna Liusgröna Linsgrönt Perlfärg Coul. De Rose Purpur Carmoise Incarnat Ponceau Skarl.färg Silfwerfärg Paille/Strå Hwita Gohlt Jonqville Citrongohlt