Eight Shades of Blue – 18

advertisement

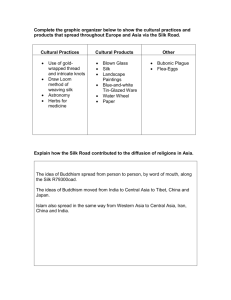

Eight Shades of Blue – 18th Century Chinese Silk on the European Market First of all, I do want to apologise for the title of this paper, I won’t talk about sex at all, I did try to find some juice reference to blue in my material but in vain. Also, the paper is not so much about the colour blue actually, at the forefront instead is how we can understand varieties of colours and what that can tell us about the import of Asian goods to European markets in the 18th century, and in extension something about the effects of Asian goods on European and Swedish consumption and production. One starting point here is that variety of colours available to consumers in 18th century illuminates the growing importance attached to surfaces, exteriors, looks, shines, and reflections to early modern Europeans. The variety of colours on Chinese silk for sale in Gothenburg, which I will talk about here, is part of this history. But it only captures a bit of it, for there were many more colours, and dye stuff, and mediums on which to display them than I could possible cover here. My blue story, which originates in China but ends up in the vast but sparsely populated pine forests of Sweden, among blue berries, juniper berries and moss, can however illuminate some of this colour history. SLIDE CHANGE I also want to say that this work in progress, which I am doing as part of a European Research Council project situated at Warwick University, on the East India trade. It is a big project, we are three post docs, and a PhD student, working with Maxine Berg. My remit is the Scandinavian East India Companies, the Danish founded in 1618 and the Swedish founded in 1731. What I will talk about here has exclusively to do with the Scandinavian trade with China. It was however going over material connected to the English East India Company that initiated my interest for colours. Comparing ordering lists from London going to India and China, I was struck by the differences in colour nomenclature, the Indian orders were very vague in specifying what colour of Indian textiles London wanted, there are constant demands for new patterns here, but very few references to other colours than blue, green and red. The orders to Canton in contrast make use of a very specific colour terminology: the largest variety was among colours that can be labelled Blue, here we find Sky blue, Bleumerant blue, Dark blue, Mazarin blue, Light blue, and Turquin Blue just to mention one group of colours. Moving on, researching the Swedish and Danish import of silk, and comparing my find with those of my colleagues in Warwick, it has become clear that the colour nomenclature used in the trade with Chinese Silk was a pan-European one. More or less the same colour terminology is used by all the European companies. What the sources left by the Scandinavian companies, and more precisely the Swedish company, can illuminate particularly well is how the import of Chinese silk seemed to respond to changing market demands in Europe. From the Swedish company we have a near unique material, in an East India Company context, namely an extensive series of sales catalogues, summarising the goods for sale in Gothenburg, the base for the Swedish East India Company. SLIDE CHANGE Here is page from the 1748 catalogue, listing the colours of pieces of silk, of the quality Posise Damask. These lots contained 30 pieces in 15 colours, as you might be able to see the prices and the buyer of the lot are also noted down. All in all I have around 20 catalogues covering the year 1733 to 1761, describing the silk for sale, the qualities, colours, prices and buyers. On the basis of this material I have created some statistical series illustrating the variety of colours, of the Chinese silk and how it changed. I can go through some of the methods and selections I have used later on if anyone is interested. SLIDE CHANGE This diagram here illustrate the colour scheme on the most popular type of Chinese Silk, Poises Damask, between 1733 and 1753. SLIDE CHANGE We can also see changes over time. This diagram here illustrate the shifting number of different shades of blue imported between 1733 and 1753. SLIDE CHANGE The imports of different colour schemes and how it changed over time, suggesting the influence of market demands in Europe are maybe illustrated better by this slide, showing the changing proportions of the overall best seller, Crimson Red, compared with the most popular blue shade, Sky blue, the third most common colour on the Chinese silk. SLIDE CHANGE Or here, illustrating how the import of the two most popular blue shades, Sky Blue and Blumerant changed over time. SLIDE CHANGE What marks out the Scandinavian East India Companies was that they were providing markets largely located outside the realm of the states in which they were situated. Between 70 and 90 % of the goods they brought to Copenhagen and Gothenburg were re-exported. This is particularly true of tea, the by far most significant Chinese goods in the Scandinavian trade. The tea was largely reexported to the Low Countries, from where shipments were smuggled into Britain, the most prolific tea consumers of 18th century Europe. What about the silk, was this also re-exported? The latter question is important because it can help us understand the extent to which the changing assortments of Chinese silk colours for sale in Gothenburg reflected changing demands in Sweden or elsewhere. Unfortunately this is a hard question to answer in a more precise manner. First of all it is necessary to highlight that by the 18th century the fashion industry, and particularly that which involved silk textiles was a very dynamic one, where silk producers in France and Britain, particularly in Lyon, introduced new patterns and colour schemes annually. This reflected a strategy, to keep abreast of the competition from other producers in Europe. By regularly introducing new trends they avoided competition from other European producers who copied the French designs. Because it took 18 months for a ship to make it to China and back the Chinese silk could not possibly keep up with the most swiftly changing trends. The trade in Chinese silk had a different rhythm to the European silk trade. SLIDE CHANGE The dominance of a French terminology for naming colours of the Chinese silk in the Swedish catalogue, and here are some examples, does however illustrate the position of France in the silk and fashion industry more generally. There is an absence of Chinese colour names, not surprisingly maybe, but worth pointing out. We can compare it to the terminology used in the trading in Chinese teas or Indian cotton fabrics, here Chinese and Indian names are used almost exclusively. The names of the colours and the types of Chinese silk textiles in contrast are largely presented with an European terminology. If anyone here can advise me the colour terminology used domestically in China in the 18th century, I would be most grateful. I do know that the term “tea colour” was used in handbooks on how to dye silk, but it is not used in by the European companies, when ordering, packing, and selling the Chinese silk. In communication with Chinese merchants in Canton, sample books were also used, bridging Chinese and European language divides. So where was these Chinese silks pieces, presented as Satins, Taffetas and Damasks, and dyed in colours described with a distinct European and particularly French sounding nomenclature consumed then? New regulations introduced by the Swedish state in the 1740s and 50s, banning import of some Chinese silk textiles, or introducing higher import duties on others, suggest that some Chinese silk initially at least was consumed in Sweden. The debate and the protests concerning the competition from China among Swedish silk manufacturers does also suggest domestic consumption. Silk of Chinese origin can also be found in historical wardrobes locates in mansions and castles in Sweden, such as these. SLIDE CHANGE SLIDE CHANGE There are however other indications that the Chinese silk also was re-exported. The sales catalogues of the Swedish Company allows me to compare the names of those buying tea in Gothenburg, of which almost all was re-exported, with those buying silk and we can see that there was a great overlap. Examples from correspondence of merchants involved in the wholesale of East India goods in Gothenburg also suggests suggest that tea and the silk travelled together to continental markets in Europe and beyond. SLIDE CHANGE Further work comparing the Swedish import with silk import by the other companies will hopefully enable me to say whether for example the Danish and the English company bought silk of the same colours as the Swedish or not. So more colour statistics can help out here. Trying to find alternative ways to also investigate the effect of the Chinese silk on the Scandinavian market I have lately stared to look into the etymology of the colour nomenclature, drawing on historical dictionaries, such as a the one produced by the Swedish Academy. It was searching for the historical use of terms such sky blue that my research took a different turn. What these studies have lead me so far, is to appreciate the long history of certain colour names describing particularly the shades of colour on silk textiles. Silk is of course a medium that absorbs dyes like maybe no other type of fibre. With silk came new vibrant colour forth. . One of the first references to sky blue in the Swedish historical word book, SAOB, includes a description of a sky blue blue dress with silver decorations. (Pufendorf Hist: “himmelsblå tygklädning med påkastade silverkvistar”). There are however some colour terms, used for the Chinese silk, such as Celadon and Olive green, that judging by historical dictionaries seems to be largely absent in 18th century Sweden. This suggests maybe only limited consumption of Chinese silk, a weak market penetration, to use a modern terminology. A closer look at some of the few references used in the Swedish Academy’s word book, namely to a book written by the Swedish lichen expert, Johan Westring, The Colour History of Swedish Lichen: or ways to use them for dyeing and other household use, published in 1805 (Svenska lafvarnas färghistoria : eller sättet att använda dem till färgning och annan hushållsnytta) lead me onto a new path, namely to handbooks advising on how to dye. SLIDE CHANGE Here finally did I re-encounter the colour terminology used in the Swedish East India Company’s sales catalogues, as well as many other colour names. This is not surprising, Sara Lowengard has explored the dynamic exchange between science, trade and colours in the 18th century. Engaged here were manufactures, scholars of different types, naturalists and physicists exchanging ideas about the nature of colours, and how to produce them. The Swedish discussion on this topic reflects this Pan-European intellectual movement. Some French, German and English books were even translated into Swedish. They reflect not only the absorption of new theories and the movement of useful knowledge across Europe, they also reflect the growing global trade, the bringing over from Asia and the Atlantic world of an ever increasing number of new substances that was incorporated into European manufacturing of colours to apply on textiles, wall paper, ink, and in fine art. There is however a counter movement to this which I would like to end this presentation talking about, which is a reaction to the growing import of global goods, a movement which produced inventories of the European landscape for sources of material that could be used as alternatives to the imported colourful stuff. This movement is part of a political economy, a form of mercantilism that sometimes is referred to as cameralism. The heartland of camerlism was the German speaking areas of northern and central Europe, it was a discussion engaging state officials, often with natural history backgrounds, mineralogists, botanists, entomologists, with the support kings and rulers. It generated an inventory of local resources, of mines, forests, and fields. Some of these activities have been looked at by Alix Cooper, in her study Inventing the indigenous. The most famous naturalist that this camerlists movement gave birth to was, suitably enough, a Swedish man, Carolous Linnaeus. You are probably familiar with Linnaeus from elsewhere, he was the inventor of binary names, the new scientific nomenclature for naming species launched internationally in 1753, in his global flora, Species Plantarum. This naming system was adopted across Europe. Linnaeus is sometimes referred to as the “Father of modern Botany”. Johan Westring, the Lichen guy, who I mentioned earlier, belonged to the last generation of Linnaeus’s students. There were however other people involved in the same Swedish cameralist projects, who predated Linnaeus. Preparing this paper last week in Uppsala, in a snow storm or white out if you excuse the pun, I came across a publication which as far as I can tell has received very little attention in previous scholarship, namely Johan Linders’ Swedish Art of Dyeing. With Domestic Herbs, Gras, Flower, Leaves, Barks, Roths, Plants, and Minerals. (Swensks Färge-konst, Med inländska Örter, Gräs, Blomor, Blad, Löf, Barkar, Rötter, Wäxter och Mineralier) SLIDE CHANGE The first edition was published 1720, this is a time when the Swedish Empire had collapsed. The “Age of Greatness” ended with the death of Charles XII in 1718; the great warrior king, and the last heir of Gustavous Adolphus, in 1718. Sweden’s economy was bankrupt after decades of warfare. It is well established that the poverty of 18th century Sweden, her inability to play a role as a super power in Europe and globally, is reflected in the writings of Linnaeus. The search for resources at home, marked a form of domestic colonialisation was was Linnaeus’ alternative, solving the economic crisis as well as giving Sweden a new role in the world. In order to achieve this, the Swedish landscape needed travelling naturalists educated by Linnaeus to explore the vast space that still constituted Sweden, at the time with Finland attached to it. Linnaeus was however not alone. Reading Linders’ account underlines how Linnaeus’ cameralism was predated by others, such as Linders, who especially promoted the use of Swedish flora and fauna to create colours matching those produced with products from around the globe, and on the continent in Europe, in Lyon, Paris, London, and different cities in German speaking land. “Snobbery” and “greed” had prevented this before Linders argues in his introduction, in which he also discusses a wide range of globally sourced substances and their longer and shorter history of use. The following sections of the book is however devoted to the replacement of foreign stuff with home grown, moving between one colour to another, from red, to blue, black, yellow, and green Linders outlines what distinctly Swedish produce could be used, and how to use them, to produce a variety of colours matching the colour schemes of foreign products. To return to the blue theme, here Linders argues for the use of blue berries, juniper berries, elderflower berries, and flowers such as Cornflowers and Larkspur, sourcing blue to use on textiles and leader, and producing art material. There is a distinct scent of vast pine forests, the most common Swedish habitat, of blueberry bushes and juniper trees that springs from these pages. Westrin’s book from almost a century later captures the end of the same tradition. It is a much more rigours book in terms of its specification of species of lichen to use, not a bad feat in itself, Lichens were an area which Linnaeus largely overlooked in his mapping of the world’s flora. Westring also discuss the exact proportions of material to use, and how to go about doing it. The book, which he dedicates both to manufactures, and matrons, mistresses of the hose, for dyeing and re-dyeing textiles, underlines the continuous strive for more colours, more variety, to make new and old everyday-object more colourful, drawing on local produce. Lichen has of course a long tradition of being used to dye textiles and particularly yarn in a household settings, it is still used today. Westrin’s ambition to teach manufacturers to draw on domestically grown resources must, against the backdrop of the birth of the chemistry industries in the 19th century, have largely failed. In this respect, Westring have more in common with the tradition of the 18th century, with Linders’ approach catering for an early modern system of producing, although 85 years separate them. There is one marked difference however, Westring’s audience is one which he imagines owns silk and cotton textiles. While wool, linen and leader almost exclusively are the materials Linders gives advice on how to dye to match the colours from abroad. Westrin’s advice also includes frequent references to silk and cotton textiles. The presence of cotton and silk material here marks of course a change in the consumption in Sweden. The silk was probably of different origin, some not unlikely were Chinese, some continental, some Swedish; the Swedish silk industry had some golden years in the 1740s, 50s, and 60s, heavily subsidises by the Swedish state. So, while the colour terminology and the political economy is similar in Westrin and Linder’works, both books reflects the habit and demands of a public who wanted colourful clothes, both were cameralists, the mediums had changed. Next to linen, wool and leader by in the early 19th century silk and cotton had been added to the wardrobes and linen cabinets of Swedish consumers. This suggest several processes at work, with different chronologies . There is an older process, one that was generated by a global trade, a dynamic European fashion industry and an early modern consumer revolution. It triggered a movement of colour schemes but not necessary the materials, such as the dye stuffs or the mediums to produce and re-produce the colours. Linders’s work reflects this process, in his advice on how to re-create colour schemes from abroad, using material sourced at home. Here indigo is replaced by juniper berries, silk by linen and wool. The inspiration is a global material culture, generating the circulation of colours as ideas, as immaterial entities. The application however, the production is local, drawing on stuff that could be sourced at home in the forests of Sweden. Then there is a more recent process, one which reflects the further integration of Sweden into the global trade and consumption, marked by the entrance of silk and cotton into the homes of the Swedish population. The dynamic of this global trade had of course also changed, the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th century marks the decline of some areas of trade, including China and India. German and British chemistry and cotton industries had become more significant, offering Swedish consumer access to new shades and previously hard to get materials, on a new scale. The Chinese silk imported by the Swedish East India Company, that I started this paper outlining the colour schemes of, is I suggest part of these complex immaterial and material global processes. The colour scheme that Chinese dyers and silk producers used, producing goods for the European markets reflects changes to fashions and trends generated in France and England. This import impacted on the consumption of silk in Sweden, increasing what was on offer, but it also had an effect on the production and look of domestic products in Sweden, not only on the silk production in Sweden, but also on the development of methods for dyeing home grown produces in a wider variety of colours, using different mediums, such as more the easily accessible wool or linen, and different sources of dye, such as blue berry pulp. SLIDE CHANGE In other words, and to conclude, the early modern globalisation of trade produced new colour schemes, a form of global immaterial culture, which travelled more quickly across the world, than the global material or physical culture or, the dye stuff and the mediums originally used to produce and present it on. It is this story the import of Chinese silk to Gothenburg can help illustrate.