Asian silk in eighteenth century Scandinavia – quantities, colour schemes... Slide change by Hanna Hodacs, University of Warwick Trading Eurasia. Europe’s Asian

advertisement

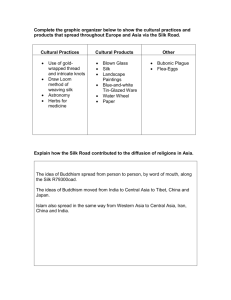

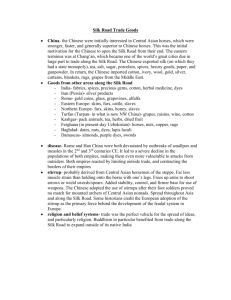

Asian silk in eighteenth century Scandinavia – quantities, colour schemes and impact by Hanna Hodacs, University of Warwick Slide change The paper I am presenting here is based on results from a project Trading Eurasia. Europe’s Asian Centuries 1600 to 18230. The project, initiated by Maxine Berg, focuses on the role of Asian goods in forming consumption and production in Europe. My project colleagues and I work on different East India companies. Slide change My remit are the Danish and the Swedish companies and their trade with China between 1730 and 1760 approximately. I am currently writing up my results in a monograph to be published by Palgrave. The working title is Silk and Tea in the North – Scandinavian Trade and the Market for Asian Goods in Eighteenth Century Europe The 1730s saw the establishment of direct trade between Scandinavia and Canton for the first time. Both companies used a the same businesses idea. Most of what they imported, and we are talking between 80% and 90 % of the goods, were re-exported from Copenhagen and Gothenburg, where the headquarters of the two companies were located. The main markets for this re-export could be found on the continent and in Britain. However this was arguably less the case with the Chinese silk textiles, at least not the ones brought back by the Swedish Company and the focus in this paper. Slide change What you can see on this picture is a cut from a sales catalogues listing Chinese silk textiles for sale in Gothenburg in 1748. The goods were auctioned away in lots and this is the first lot, contained 30 pieces of Poisies Damask. Next to the type of textile there is information on the dimensions, and, most importantly here, the colour assortments of the lot. Just to give you some idea of what the colours actually looked like, here are some pictures from Anders Berch’s collection which does include samples he received from the Swedish company, not all of it of course Damask pieces. Silde change x 5 Here are some pictures of eighteenth century silk clothes in Swedish collections, which I have been told very likely are Chinese in origin. Slide change x 2 Slide change It was the colour schemes that initially drew my attention to the trade in Chinese silk. One aim I have is to capture the role of Chinese silk, but also more generally Asian textiles, on the Scandinavian market focusing particularly on colours. What I will do here is to explore a few different ways by way we can use colours tracing changes to the trade and reception of silk. This Scandinavian trade is of course part of the history of Asian textiles in Europe more generally; how it came to influence European consumption and production. The role of Asian cotton textiles in this process have been explored in several different contexts, very prominently by Giorgio Riello and his work on British and French developments. We know now how Indian cotton cloths, calicoes and chintzes, decorated with vivid colour fast colour prints or paintings became the object of desire for European consumers from different socio-economic groups. The growing trade in Indian textiles in the eighteenth century triggered import bans and import substitutions in Europe; institutional changes that together with knowledge transfer, were instrumental in promoting an European manufacturing of cotton, a process of central importance to the industrialisation that followed. Silk, the production of which originated in China, has of course a history that predates the maritime trade of the European East India companies, it was a product that gave name to the land route on which gods travelled across the Eurasian continent. Moreover, silk and silk textiles were produced in Europe long before the 18th century, particularly in Italy, France and Britain. Europe had a vibrant silk culture with Lyon, Paris and London becoming centres in silk fashion. The regular invention of new trends reflected on the ambition of the most prominent central producers to stave off competition from manufacturers elsewhere in Europe. By the eighteenth century the wheel of fashion generated new patterns and new colour schemes on an annual basis, trends that reverberated across Europe. Slide change The influence of this long history of European silk consumption and production is clearly visible in the Scandinavian trade in Chinese silk. The types of silk traded by the Scandinavian companies were largely the same; different types of Damask, Satin, Taffeta were some of the most common types. These are types of weaves we are familiar with from the European production of silk textiles. The colour schemes are also familiar. Listed on the slide are the translated Swedish terms for colour names such as sky blue, himmelsblå, and citron, or lemon yellow, citrongul. French names for colours, such as Pounce and Couluer de Rose, were also adopted in the Scandinavian trade. As were, although not listed here, names reflecting the growing global trade. Different shades of brown were regularly described with references to coffee, chocolate, and cinnamon. Judging by the colour nomenclature and types of weaves imported, the Chinese silk import corresponded largely with what was produced and consumed in Scandinavia and Europe already. If anything Eurasian silk textiles were fairly homogenous products, at least if we take into account the testimonies of museum curators. The geographical origin of early modern silk textiles that have survived in museums are often very hard to determine only by looking at them. We can contrast this with the trade in Indian cotton which generated a lot of imitation and innovation in the 18th century. There is little in the research on Chinese imported silk that suggest that it inspired “desire lead” product imitation of a similar kind.1 The sources I have worked with seem in fact to suggest that large bulk of Chinese silk that made its way to Europe in the eighteenth century conformed to European product standards more than anything. 1 Berg, see ref in Riello global colours Slide change I have for example found very little evidence of Chinese colour terms penetrating the Eurasian trade. Take the term “tea colour” which was used in Chinese handbooks for dying silk from the 17th century. It refers by all account to a light yellow shade, reminiscent of the colour of brewed green tea, the type of tea preferred by the Chinese. The term tea colour was used by the Chinese who provided the Europeans with silk textiles, in fact Paul van Dyke has found references to this colour in material relating to smuggling in Canton. The reason yellow, or here tea coloured textiles, were smuggled was that the emperor and his court had exclusive use of this colour, and red. This circumstance promoted an elaborate system for bribing the Chinese inspectors employed to monitor the European East India companies trade activities. Without much effect, as we shall see below vast amounts of yellow and red silk textiles made it to Europe. The colour term “tea colour” did however no travel onwards with the goods, instead terms such as jonquille, citron, and straw are used to describe colours of a yellow nature. With one possible exception, Mandarin green, I have found no evidence for any Chinese colour references making its way into the trade between Scandinavia and China. In fact there is a somewhat notable lack of innovation and change. Danish material relating to the negotiation with Chinese merchants about silk orders suggest a very standardised trade. Danish supercargoes instructed their Canton counter parts on the types of weaves, dimensions, patterns and colour schemes, the phrase “the best colours the land of China could offer” was used regularly in contracts. The Chinese merchant forwarded the orders to silk manufactures inland who took up to 3 months to deliver the goods. There were no direct contact between the Europeans and the Chinese weavers or dyers. While the negotiations on patterns seemed to have involved prototypes there are few examples of sample colour books being used or at least referred to in the exchange between the Danes and the Chines. Another notable aspect is that the trade in itself seem to have generated relatively few problems or conflicts. Not only did colour and pattern specification seemed have been communicated with ease, there are only a few examples in the sources of Danish complaints that the silk goods did not meet the specifications stipulated in the contract. When there were problems they seemed to be well known ones, for example that purple or Cherry red coloured silk pieces had a tendency to run, and lighter colours did easily spot. Slide change Comparing description of goods traded by the Danes with goods traded by the English and Swedish suggest similar procedures and similar standards, not at least when it comes to the colour schemes, the same colour nomenclature is used by more or less all companies. The company trade was of course not the only type of trade going on in Canton. Accounts from private trade in silk do also suggest a slightly different dynamic, where more attention was being paid to the colour schemes, including requests for more unusual colours. It is among privately traded goods we find references to “Dark sky blue”, “Light Sky blue”, “Light Cherry”, “Dark Cherry”, and “French Green”, colours I have not seen referred to in any Company trade. Overall though the Company silk trade and most of what I found relating to private silk trade involve what by all account was a standardised colour schemes and standardised product types. The impression is further reinforced if we look closer at colour schemes of Poisies Damask pieces put up for sale by the Swedish East India Company. This was the most common type of silk imported by the Swedish Company. An incomplete series of sales catalogues from 1733 to 1761 suggest that at least 24,125 pieces of Poisies Damask were imported, and that they came in 38 different colours or shades. As this graph describes, the top four colours was Crimson, followed by White, Jonquille yellow, Sky blue etc. Slide change Although it was the most common textile type imported by the Swedish company, and the EIC did also order vast amounts of it, there is actually some debate about what Poisies Damask refers to, what type of silk it was. Leanne Lee-Whitman has speculated that Poises Damask referes to a form of decorated (painted and printed) satin on the basis of the similarities between the weight of the satin and the Poisies Damask pieces imported from China by the English company. This interpretation is supported by the Swedish case; silk labelled satin or “satin for lining” formed only a small share of the Scandinavian import. Slide change The comparably wide colour assortment, this graph, again based on the incomplete Swedish sales catalogues, suggest that Poisies Damask usually came in a wide variety of colours. This I think suggest it was used for clothing. In fact the Danish material use “Klädes Damask” or “Cloth Damask” as a synonym for Poisies Damask. I think we can assume that textiles used in clothes were more sensitive to changing colour trends than for example textiles used in furnishing. Chinese Meuble Damask was typically only imported in a handful of colours. In the light of this, a closer study of how the colour scheme of Poesies Damask changed should reveal the extent to which the trade with Chinese silk was sensitive to changing fashions in Europe. With this mind I have tried to trace the changing colour schemes of the Poisies Damask: Is it possible to detect any trends? Well yes, although it is hard to represent and explain the change. Slide change In this graph I have grouped the colours into five different categories bringing the different shades of red (Crimson, Poppy, Scarlet, Incarnat, and Cherry); blue (“Dark”, “Middle”, “Light”, “Mazarine”, “Millan”, “Bleumerant”, and “Sky”); yellow (“Jonquille”, “Lemon”, “Paille”, and “Yellow”); green (“Celadon”, Light, “Dark” and “Green”), and Grey (“Pearl, Lead, and Silver) together. Some of the trends described by the graph can be connected with observations and comments in other material relating to the trade in Canton. For example Black, was very common across different types of Chinese silk textiles in the beginning of the 1740s, in both companies. And here I wonder if it corresponds events in Europe, possibly some declaration of official mourning, generating a larger demand for black clothes. In general it seemed a safe bet, as the Danish supercargo, Christian Lindrup put it, “black never goes out of fashion”. In other respects, the graph might suggest that the Swedish East India Company played quite a safe game, importing a relatively broad spread of colours. However, and although for the sake of clarity, using colour categories such as e.g. red and blue is helpful, it is also rather counter intuitive. The specific colour nomenclature used in the Chines-European silk trade reflected of course a need to distinguish between the many different types of blue and red. If we study changes over time within the broader colour categories rather than between them we can also pick out some notable trends. Slide change Take the case of red illustrated by this graph. It suggested that Crimson dominated the red colour spectra between 1752 and 1761, between 2/3 and 9/10 of all red pieces were Crimson, the only other red colour was Poppy red. Crimson was strong before too but less dominating. (constituting only a quarter of red pieces in 1733, Poppy red and Incarnat making up more than a third each of the other red pieces in the first Swedish cargo of Poisies Damask). Slide change Among the blue colours we have almost a reversed development, Sky blue was by far the most dominating shade of blue in the beginning of the period. In 1733 nearly 4/5 of all blue pieces were Sky blue. Although this declined by 1748 still half of the blue pieces were Sky blue. The next year however there was no Sky blue Poisies Damask at all for sale. The new dominant blue, making up more than 7/10 of the blue pieces in 1749 and more than half of the pieces in 1751, was Bleumerant blue. Although the Sky blue shade returns (making up more than half of all blue pieces 1757) there are several years (1752-55, 1758, 1761) when there are no Sky blue or Bleumerant coloured pieces put up sale. Instead the blue Poisies Damask cargo was made up of Light blue, Millan blue and Dark blue in approximately equal proportions. It could of course be the case that the colours remained the same while the name changed. Maybe the illusive Millan blue was the same as Sky Blue; there is no single batch of Poisies Damask contained pieces in both colours. Shifts in the colour schemes on the Chinese silk did in other words take place, something that makes sense in the light of the careful specifications of colours in ordering lists, contracts, and sales catalogues, or for that matter in material relating to private trade; colours mattered. However, and although the colour schemes on the silk cargo reflected changing European demands they could not possibly have followed the fashion rhythm of the silk trade in Europe since it took eighteenth months for a ship to make it to Canton and back. In addition to the somewhat slower demand and supply system of the East India companies one need also to take into account how the silk goods was sold on in Europe, in the whole sale trade that linked auctions to retail trade. As the slide from the Swedish Auction catalogue showed, lots containing pieces of several colours were packed together and sold together. This whole sale system seemed to have impacted the colour schemes of the silk cargo. Slide change There is for example evidence that the purchasers in Gothenburg paid extra for lots with more variation, at least in the case of Poisies Damask. Take for example the 4310 pieces of Damask first listed in the Swedish sales catalogue from Cronprinzen, arriving in Gothenburg in 1748. These pieces were sold in lots containing between 29 and 37 pieces each, they were all of the same length, that is 16.5 meters long. There is however a notable difference in price between lots with more colour variation compared to a lot with less. The highest price was paid for the 30 lots with the lot numbers 934-to 964, they caught an average price per piece of 55.89 silver dollar. Each of these lots contained 31 pieces in the same 16 different colours. In contrast the lowest price, 44.75 silver dollar per piece, was paid for the last lot (nr 1016), which contained 37 pieces in 6 different colours. For the type of textiles that came in the largest compilation of colours, like Poisies Damask and taffeta, more variation in the lots tended to promote higher prices at the auctions. This explains the for example the instructions from Copenhagen to the Danish supercargoes. When buying silk they were repeatedly told to make sure they kept to the colour proportions stipulated in the orders. How many pieces they bought were less important. In other words, to a certain extent “more was more”, a broader variation of colours per lot promoted a higher price. But even if the China trade promoted colour variation it did not necessary promote colour innovation. As the 24,125 pieces of Poisies Damask put up for sale by the Swedish company illustrate, there are remarkably few new colours being introduced between 1733 and 1761. Instead the same colours disappear and re-occur. It is of course an open question to which extent this lack of change was the result of how the wholesale trade was organised, how the silk was sold on at the company auctions in multi-coloured lots, or to which extent it reflected on how the Eurasian silk trade was organised, with few contacts surfaces between producers, Chinese weavers, and traders, European supercargoes. Maybe the institution of Hong merchant prevented innovation? Slide change A third factor was of course consumer demand. Here the Scandinavian sources provide very little information. Where the bulk of the Swedish silk was consumed is an open question. Statistic I compiled over the numbers of pieces imported by the Swedish company, excluding smaller and very cheap pieces such as Pelongs and silk handkerchiefs, show that the ban on domestic import instituted by the Swedish state in 1754, effected the trade negatively. The import of silk for re-export was however not banned, which explain the increase in the late 1750s. The growing silk import then does probably reflect the effect of the Seven year war, this meant the price of Bohea tea, the most important goods imported by the Scandinavian companies went down. There seemed also to have been more credit available on the Canton market, making it cheaper to borrow money with which to purchase Chinese goods for, particularly if you were based in a small neutral country. The regulation of 1754 as well as earlier regulations of specific types of goods, suggests that Chinese silk did find a market in Sweden. Unfortunately I have found very little material with which help we can trace the domestic end of this trade. The political debate concerning the restrictions on Chinese silk help can however us a bit on the way. The privileges of the Swedish company, and particularly its trade in silk textiles evoked opposition among representatives for Swedish manufacturers, and particularly those involved in textile production and retail. The discussion followed patterns familiar from other European countries, the company and the import from China was pitched against the progress of domestic industries. Those critical against the trade with China said it undermined the Swedish industry, Sweden should be exporting not importing silk. Those in favour of the Swedish company said that Chinese silk filled a gap in the market, arguing that Swedish silk manufacturing was mainly targeting the top end of the market. French and Italian silk was the main competitor here, not Chinese silk, the cheapness of which allowed it to be bought by less well-off consumers. Moreover, it was claimed that Swedish silk manufacturers were not able to produce enough to keep domestic consumers provided with textiles. To which extent the defenders of the company were right is of course hard to say. But the argument that Chinese silk textiles were largely supplying a segment of the market that could not afford the Swedish or the continentally produced silk textiles was repeated in responses from staple towns and municipals asked to comment on the effect of the East India trade in Sweden in conjunction to the renewal of the charter in 1746. While Chinese silk textiles might have penetrated the Swedish market, it is however important to acknowledge that generally speaking Sweden, together with the rest of northern Scandinavia, Norway and Finland, was not a scene for a consumer revolution similar to anything that took place in Britain, the Dutch Republic of France in the eighteenth century. Historians discussing the traces of consumer changes and the existence of an industrious revolution in the Northern part of Scandinavia tend to agree that major changes only took place in the beginning of the 19th century. This does of course not mean that Asian or for that matter Continental material culture failed to make an impact in other respects. Taking colours as a cue we can trace some of the effects of colourful Asian textiles in Swedish handbooks and advice literature on dyeing. Many of these were written by naturalists and a common strand in this genre was the that Swedish natural resources provided import substitutes for dyes which otherwise had to be imported from abroad. With the help of blueberries and lichen the colour schemes of Indian cotton, Chinese silk as well as silk and woollen textiles from continent, could be recreated on Swedish produced wool and linen these naturalist argued. Although such claims were aspirational rather than reflecting a common practice they do tell us of a change of horizon, but also how Asian material culture became translated into a distinct Swedish context. Moreover, this genre offer possibilities to study several changes taking place over the cause of the 18th century. Different fibres respond differently to different dyes, and the growing number of recipes in the handbooks, specifying what dyes to use not only for wool and linen but also for silk and cotton, illustrate changing consumer habits. More significantly here perhaps, the variation of colours that the naturalists argued could be had from Swedish harvested resources, expanded reflecting a growing exposure to a continental European consumer cultures, often steeped in French. I want to end with an example from Johan Westring’s The Colour History of Swedish Lichen, or how to use them for colouring and in other useful ways for the household, published in the first decade of the nineteenth century. As the title suggest Westring encouraged the use of Lichen to produce dyes. Drawing on hundreds of experiments applying lichen made dye matter on wool, linen, silk and cotton pieces he presents his potential reader with ample opportunities to reproduce what he called “modern” colours, identified by a largely French nomenclature. One of the many brown colours Westring hoped to promote using the lichen Mountain Saffron was one he called, “Thé au lait”. Although the Chinese term tea colour referring to what we think of yellow did not penetrate the Eurasian silk trade tea as a reference did travel, not surprisingly, since tea became such a popular beverage in Europe, but not of course in its green version. “Thé au lait” refers to a shade reminiscent of milky black tea, which was the most popular way of having tea in Europe. It is also worth noticing that the colour term is in French, the dominating language of European fashion although Britain was the number one tea drinking nation in Europe and the receiver of the bulk of the Swedish East India tea imports, smuggled across the North Sea. Swedish consumer in contrast drank very little tea. What Westring’s recipe for “Thé au lait” producing dye do illustrate how material culture travelled across the Eurasian continent. Colours and colour references could travelled separately from fibres and dyes, this detachment open up for innovation, allowing for the incorporation of new substances such as Mountain Saffron, a lichen growing above the polar circle, and changing points of references, including new consumer patterns, such as the habit of drinking black tea and milk.