Immaterial and material cultures: Asian colour schemes and domestic

advertisement

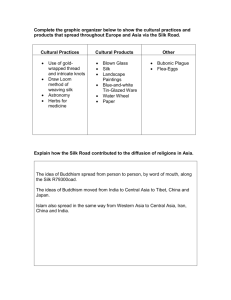

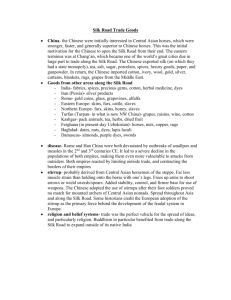

1 Immaterial and material cultures: Asian colour schemes and domestic dyes in eighteenth-century Sweden1 Hanna Hodacs, University of Warwick Work in progress please do not circulate or quote it without permission The early 1730s saw the establishment of direct trade between Scandinavia and Canton. Both the Danish and the Swedish East India Company used a the same businesses idea; most of what they imported, between 80% and 90% of the goods, were re-exported from Copenhagen and Gothenburg to markets on the European Continent, in Britain, and elsewhere. This re-export reflects the extent to which Scandinavia was somewhat peripheral to the Consumer Revolution of the eighteenth-century. With the possible exception of main land Denmark there was no Nordic equivalent to the broader changes of consumer habits we can find in France, Britain and the Low countries. The northern economics of what is present day Norway, Finland and Sweden were instead shaped by a relatively high degree of self-subsistence. As Ragnhild Hutchison recently demonstrated in relation to early modern Norway: when members of a household supplemented their living off the land with work in export sectors such as for example fishing or forestry, they were largely driven by the need to reduce risk associated with being too dependent on only one sector of the economy.2 Survival rather than luxury consumption was the overriding motive for the majority; a rational different to the ones at the centre for what Jan De Vries has labelled the Industrious Revolution.3 Moreover, towns and cities which could foster consumer cultures around the new exotic global goods were few and far between in the North. In other words, in contrast to the Low Countries, Britain and France, there was no domestic mass consumption in Scandinavia that can be linked to the trade of Danish and Swedish East India companies in the eighteenth-century. However, there are exceptions to this and above description is arguably somewhat less correct when it comes to the case the Scandinavian import of Chinese silk textiles and particularly silk textiles brought back by the Swedish East India Company before a total import ban of Chinese silk for domestic use was introduced in 1754. The case of Chinese silk textiles in Eurasian trade is different to that of Asian cotton. Indian cotton pieces such as calicoes and chintzes, decorated with vivid colour fast colour prints or paintings, became the object of desire for European consumers from different socio-economic groups in eighteenth- century. This development triggered import bans and import substitutions in Europe; institutional changes that together with knowledge transfer were instrumental in promoting an European manufacturing of cotton, a process of central importance to the industrialisation that 1 The following paper is based on results from the ERC funded project Trading Eurasia. Europe’s Asian Centuries 1600 to 18230. Initiated by Maxine Berg it focuses on the role of Asian goods in forming consumption and production in Europe. As a Research fellow on this project I have worked on the trade of the Danish and the Swedish East India companies with China between the 1730s and the 1760s. I am currently writing up my results in a monograph to be published by Palgrave. (The working title is Silk and Tea in the North – Scandinavian Trade and the Market for Asian Goods in Eighteenth Century Europe.) 2 Ragnild Hutchison, In the Doorway to Development. An Enquiry into Market Oriented Structural Changes in Norway ca. 1750-1830, Brill, 2012. 3 Jan De Vries, The Industrious Revolution: Consumer Demand and the Household Economy, 1650 to the Present. Cambridge, Cambridge Univ. Press, 2008. 2 followed in the late eighteenth century and the beginning of the nineteenth-century.4 The trade in silk textile, the production of which originated in China, has of course a history that predates the maritime trade of the European East India companies. Silk gave name to the land route on which gods travelled from China and across the Eurasian continent from antiquity and onwards. Moreover, silk and silk textiles were produced in Europe since the 6th century. By the eighteenth-century Europe had a vibrant silk production; Lyon, Paris and London were important centres in the making of silk based fashion. The regular invention of new trends reflected on the ambition of the most prominent central silk producers to stave off competition from manufacturers elsewhere in Europe. By the eighteenth-century the wheel of fashion generated new patterns and new colour schemes on an annual basis, trends that reverberated across Europe.5 It did also result in labour migration. The silk manufacturing that evolved in Stockholm in the late 1730s and 40s was largely organised by French and other skilled continental workers. How does the Scandinavian import of Chinese silk textile fit into this picture? Let’s start with an example. What you can see below (Illustration 1) is a part of the sales catalogue listing Chinese silk textiles for sale in Gothenburg in 1748. Illustration 1. Sales catalogue for the cargo of the ship Calmare and Cron-Printzen Adolph Friedrich, put up for sale in Gothenburg in August 1748. Source: Kommerskollgiums arkiv. Enskilda arkiv inom kommerskollegium, Ostindiska kompaniet, vol. 10. Riksarkivet, Stockholm. 4 See e.g. Riello, Giorgio, Cotton: the fabric that made the modern world, Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 2013 and Lemire, Beverly, Fashion's favourite: the cotton trade and the consumer in Britain, 1660-1800, Pasold Research Fund [in association with] Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1991. 5 Carlo Poni “Fashion as flexible production: the strategies of the Lyons silk merchants in the eighteenth century” in World of Possibilities. Flexibility and Mass Production in Western Industrialization, Ed. Charles F. Sabel and Jonathan Zeitlin, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 37-74. 3 We are told that the textiles were on display in the merchant house of Johan Friedrich Bruun, situated in the Great Harbour, where potential purchasers could inspect the goods prior to the auction. The silk sale started with a rather large batch of textiles, 4310 pieces of poesis damask, the dimensions which are specified with help of Swedish alnar (I aln=0.60 m). This suggests that each piece was approximately 16.5 meters long. The width is not specified but described as “ordinary”; on the basis of other posts in the catalogue it is likely this meant a width of 1.25 meter. What is specified with a great degree of care is the range of colours in which the goods came. The first series of lots contained thirty pieces assorted in fifteenth different colours. Crimson and Sky blue were the most common ones (four pieces each); followed by Green and Jonqville (three pieces each). There were also two each of pieces died Asch grey, Mazarine blue, Ponceau (or Cherry), Scarlet, White, and one each of Brown, Turquvin blue, Citron Yellow, Pearl, Lead, and “Colour de Rose” dyed pieces. What exactly this colour nomenclature refers to in terms of specific shades is hard to determine exactly. Collections, such as Anders Berch’s at the Nordiska Museum in Stockholm, which contains a long sequence of silk textiles samples referred to as “East Indian”, can give us some idea of what was on display in Bruun’s house.6 However, and although we might struggle defining what exactly for example Mazarine blue refers to, the variation itself as well as the colour nomenclature can still help us explore the trade between Scandinavia and China, what characterised it, how it changed, but also how to understand it from the point of view of eighteenth century material culture and consumption. This paper will discuss different aspects of the Scandinavian trade in Asian textiles and particularly Chinese silk textiles using colours as the focal point. The idea is to explore what colours can tell us about the Scandinavian trade, consumption, and reception. The first part of the paper discusses the Canton-end of the market and how colours can illuminate how this marked worked. Colour trends in the Swedish import of poesis damask pieces is discussed in the second part while the third part focuses on how silk textiles were sold on, and how wholesale market can have influenced the colour composition of the Chinese silk cargo. The forth part of the paper discusses the domestic market for silk in Sweden and how colours can help us understand the reception of Asian textiles more generally. In the paper I shall draw on both Danish and Swedish sources. A need for such an approach is generated by the uneven distribution of the primary evidence covering different aspects of the trade. While archive material reflecting the trade in Asia is well preserved in the case of the Danish East India Company very little material reflecting the re-export once the goods had reached Copenhagen has survived. In the Swedish case the situation is reversed, very little material has survived which illustrates the trade in Asia; a range of sources illustrating the wholesale market for Asian goods imported to Gothenburg has however survived. On the limits of Chinese-European colour exchange – the example of tea coloured silk The different types of silk weaves, most prominently Damask, Satin and taffeta, imported from China to Europe in the eighteenth-century were familiar to European consumers. As such they underline the long history of Eurasian exchange when it comes to silk consumption and production; a feature that makes it hard for museum curators today to establish the provenance of eighteenth century 6 Nordiska museet, 1700-tals textil: Anders Berchs samling i Nordiska museet = 18th century textiles : the Anders Berch Collection at the Nordiska museet, edited by Elisabet Stavenow-Hidemark. Nordiska museet, Stockholm, 1990. 4 silk. Related to this problem is also the issue of change and its geographical location. Typically the growth of a European and particularly British cotton industry in the eighteenth century has been understood as a “desire lead product imitation, a process in which Indian cotton Calicoes and Chintzes inspired Europeans.7 Chinese porcelain triggered similar reactions in Europe, ending in the establishment of the first manufacture of “true porcelain” in Meissen in 1710. There are examples of embroidery designs moving between Canton and Europe in a similar fashion to how designs applied on porcelain circulated along the same route. However, apart from this the East India import of Chinese silk seemed to have provoked few if any responses in the form of imitations or innovations, neither in China nor in Europe. Although a study of the colour scheme on the Chinese silk do not contradict such an impression, it might provide us with a fuller understanding of why. Take the term “Tea colour” which was used in Chinese handbooks for dying silk from the seventeenth-century. It refers by all account to a light yellow shade, reminiscent of the colour of brewed green tea, the type of tea preferred by the Chinese. The term tea colour was also used by the Chinese who provided the Europeans with silk textiles; Paul van Dyke has found references to this colour in material relating to smuggling in Canton. The reason yellow, or here “tea coloured” textiles, were smuggled was that the Emperor and his court had exclusive use of this colour, and red. This circumstance promoted an elaborate system for bribing the Chinese inspectors employed to monitor the European East India companies’ trade activities.8 Without much effect, as we shall see below vast amounts of yellow and red silk textiles made it to Europe. The colour term Tea colour did however no travel onwards with the goods, instead terms such as Jonquille, Citron, and Straw were used to describe colours of a yellow nature on the Chinese silk that reached Europe. How a term such as tea colour was lost in translation is hard to trace in the material that has survived the trade in Canton. Ordering lists from Copenhagen specified the numbers of pieces of each quality and the colour assortments of each batch the headquarters wanted. Due to several circumstances the supercargoes were often left to decide whether to buy any silk textiles at all. What they were not allowed to do was to diverge from the proportions of different colours stipulated in the orders; colours described with the help of a nomenclature more or less identical to the one used in the Swedish sales catalogue pictured in Illustration 1. This was not a terminology unique to the Scandinavian companies rather it was used across the European companies when ordering, buying and selling silk. It was a Pan-European nomenclature made up of a mix of established French and translated terms (e.g. sky blue, himmelsblå). Material relating to the Danish silk contract do not tell us much about how colours were negotiated beyond what was ordered and contracted, and here again the standard European terms were used. Often repeated phrases in the contracts with Chinese merchants were requests for “the best colours the land of China could offer”.9 There are also notably few conflicts regarding colours. Aside from problems that were well known, for example that purple or cherry coloured silk pieces had a tendency to run and that lighter colours did easily spot, negotiating the colours on the silk seemed 7 Maxine Berg, “From Imitation to Invention: Creating Commodities in Eighteenth-Century Britain”, The Economic History Review, New Series, Vol. 55, No. 1 (Feb., 2002), pp. 1-30. 8 Paul van Dyke, Weaver Suckin and the Canton Silk Trade 1750-781, Review of Culture, International Edition No. 29 (2009): 105-19. 9 Neg. Protocol China trade, DA. 5 to have been a pretty straight forward process.10 It is not unlikely that colour sample books were used; there are references to such books in the private trade. Accounts from private trade in silk suggest individuals operating outside the company had a somewhat different and more specific idea about what would sell in Europe. Among privately traded goods we find references to for example “Dark sky blue”, “Light Sky blue”, “Light Cherry”, “Dark Cherry”, and “French Green”, colours not requested in the Scandinavian company trade.11 Aside from these examples there is little evidence for colour innovations taking place or new trends evolving in Canton and then becoming diffused to Europe. Why is hard to say, it might have to do with how the silk trade was organized. In contrast to tea and porcelain, which the European merchants bought in Canton selecting from what was on offer, silk orders were placed with Hong merchant who forwarded them onwards, to manufactures inland who took up to three months to deliver the goods. There were as far as I know no direct contact between the Europeans and the Chinese weavers or dyers. Maybe the absence of a “shop-around” process helps explain why changes to colour schemes did not evolve in Canton? Changes of colours over time: the example of poesis damask What about changes to colour schemes initiated from the European side? The example of the Swedish import of poesis damask offers an opportunity to study changes over time. Poesis damask was the most common type of silk imported by the Swedish Company (see Graph 1); this was not unusual, both the English and the Danish companies imported large quantities of the same type. Graph 1. Pieces of poisies damask imported and colour variation (number of colours) Source: Försäljningskataloger (Sales catalogues), vol. 1-21 (1733-1759), Enskilda arkiv inom Kommerskollegium, Ostindiska kompaniet, Kommerskollegiums arkiv, RA, Stockholm, and Göteborgs Landsarkiv, Öjareds Säteri arkiv FIII:4, Försäljningsbok för skeppet Stockholm Slott. 10 11 Neg. Protocol China trade, DA. Irvine correspondence, 20th of Jan 1745, James Ford Bell Library. 6 However, there is actually some debate about what poisies damask refers to, what type of silk textiles it was. Leanne Lee-Whitman has speculated that it was the name of a form of decorated (painted and printed) satin on the basis of the similarities between the weight of the satin and the poisies damask pieces imported from China by the English company.12 This interpretation is supported by the Swedish case; e.g. silk labelled satin (sometimes also “satin for lining”) formed only a small share of the Scandinavian import. What was poesis damask used for? The comparably wide colour assortment of the poesis damask does suggest it was used for clothing. In contrast to Chinese meuble damask (used in furnishing and hence not as sensitive to changing fashions) which was typically only imported in a handful of colours poesis damask was regularly imported in up to fifteen, sixteen even eighteen colours (see Graph 1). The fact that the Danish used Klädes Damask (“Cloth Damask”) as a synonym for poisies damask supports this interpretation. Graph 2: Colour scheme on Poisies Damask textiles (24125 pieces) imported by Swedish East India Company 1733 to 1761, relative numbers. Source: Försäljningskataloger (Sales catalogues), vol. 1-21 (1733-1759), Enskilda arkiv inom Kommerskollegium, Ostindiska kompaniet, Kommerskollegiums arkiv, RA, Stockholm, and Göteborgs Landsarkiv, Öjareds Säteri arkiv FIII:4, Försäljningsbok för skeppet Stockholm Slott. In the light of this a closer study of how the colour scheme of poesies damask changed should tell us something about the extent to which the trade with Chinese silk in Scandinavia was sensitive to changing demands, changing fashions. In Graph 2 I have tried to trace changes to the colour schemes of the Swedish imported poisies damask: Is it possible to detect any trends? Well yes, although it is hard to represent and explain the change. In the graph I have grouped the colours into five different categories bringing the different shades of red (Crimson, Poppy, Scarlet, Incarnat, and Cherry); blue (“Dark”, “Middle”, “Light”, “Mazarine”, “Millan”, “Bleumerant”, and “Sky”); yellow 12 Leanna Lee-WhitmanSource “The Silk Trade: Chinese Silks and the British East India Company”, Winterthur Portfolio, Vol. 17, No. 1 (Spring, 1982), pp. 31-32. 7 (“Jonquille”, “Lemon”, “Paille”, and “Yellow”); green (“Celadon”, Light, “Dark” and “Green”), and Grey (“Pearl, Lead, and Silver) together. Some of the trends described by the graph can be connected with observations and comments in other material relating to the trade in Canton. For example Black was very common across different types of Chinese silk textiles in the beginning of the 1740s in both the Scandinavian companies. And here I wonder if it corresponds with events in Europe, possibly some declaration of official mourning, generating a larger demand for black clothes. In general black seemed to have been a safe bet, as the Danish supercargo, Christian Lindrup put it, “black never goes out of fashion”. In other respects the graph suggests that the Swedish East India Company played quite a safe game, importing a relatively broad spread of colours. However, and although for the sake of clarity, using colour categories such as e.g. red and blue is helpful, it is also rather counter intuitive. The specific colour nomenclature used in the Chines-European silk trade reflected of course a need to distinguish between the many different types of blue and red. Graph 3. Different shades of red on Poisies Damask pieces imported by the Swedish East India Company 1733-1761 Source: Försäljningskataloger (Sales catalogues), vol. 1-21 (1733-1759), Enskilda arkiv inom Kommerskollegium, Ostindiska kompaniet, Kommerskollegiums arkiv, RA, Stockholm, and Göteborgs Landsarkiv, Öjareds Säteri arkiv FIII:4, Försäljningsbok för skeppet Stockholm Slott. If we study changes over time within the broader colour categories rather than between them we can also pick out some notable trends. Take the case of red illustrated in graph 3. It suggested that Crimson dominated the red colour spectra between 1752 and 1761, between 2/3 and 9/10 of all red pieces were Crimson, the only other red colour was Poppy red. Crimson was strong before too but 8 less dominating constituting only a quarter of red pieces in 1733, Poppy red and Incarnat making up more than a third each of the other red pieces in the first Swedish cargo of poisies damask. Among the blue colours we have almost a reversed development; Sky blue was by far the most dominating shade of blue in the beginning of the period. In 1733 nearly 4/5 of all blue pieces were Sky blue. Although this declined by 1748 still half of the blue pieces were Sky blue. The next year however there was no Sky blue Poisies Damask at all for sale. The new dominant blue, making up more than 7/10 of the blue pieces in 1749 and more than half of the pieces in 1751, was Bleumerant blue. Although the Sky blue shade returns (making up more than half of all blue pieces 1757) there are several years (1752-55, 1758, 1761) when there are no Sky blue or Bleumerant coloured pieces put up sale. Instead the blue poisies damask cargo was made up of Light blue, Millan blue and Dark blue in approximately equal proportions. Shifts in the colour schemes on the Chinese silk did in other words take place, something that makes sense in the light of the careful specifications of colours in ordering lists, in contracts, and sales catalogues, or for that matter in material relating to private trade. Together they suggest that European demands dictated the market. There is however more to the story than changing trends and fashion in Europe, we need also to take into account the logistic of the China trade and the whole sale market for Chinese silk. Selling silk in Gothenburg – the whole sale explanation Although the colour schemes on the silk cargo reflects on changing Scandinavian demands they could not possibly have followed the fashion rhythm of the silk trade in Europe since it took eighteenth months for a ship to make it to Canton and back. In addition to the somewhat slower demand and supply system of the East India companies one need also to take into account how the silk goods was sold on in Europe, in the whole sale trade that linked auctions to retail trade. As the image from the Swedish sales catalogue showed, lots containing pieces of several colours were packed together and sold together. This whole sale system seemed to have impacted on the colour schemes of the silk cargo. There is for example evidence that the purchasers in Gothenburg paid extra for lots with more variation, at least in the case of poisies damask. Take for example the 4310 pieces of Damask first listed in the Swedish sales catalogue from Cronprinzen, arriving in Gothenburg in 1748. These pieces were sold in lots containing between 29 and 37 pieces each, all of the same length (16.5 meters). There is however a notable difference in price between lots with more colour variation compared to a lot with less. The highest price was paid for the 30 lots with the lot numbers 934-to 964, they caught an average price per piece of 55.89 silver dollar. Each of these lots contained 31 pieces in the same 16 different colours. In contrast the lowest price, 44.75 silver dollar per piece, was paid for the last lot (nr 1016), which contained 37 pieces in 6 different colours. 9 Table 1. Highest and lowest price paid for poesis damask pieces (of identical dimensions) at the public sale in Gothenburg, August 1748 Source: Kommerskollgiums arkiv. Enskilda arkiv inom kommerskollegium, Ostindiska kompaniet, vol. 10. Riksarkivet, Stockholm. For the type of textiles that came in the largest compilation of colours, like poisies damask and taffeta, more variation in the lots tended to promote higher prices at the auctions. This explains for example the instructions from Copenhagen to the Danish supercargoes. When buying silk they were repeatedly told to make sure they kept to the colour proportions stipulated in the orders; how many pieces they bought were less important. In other words, to a certain extent “more was more”, a broader variation of colours per lot promoted a higher price. But even if the China trade promoted colour variation it did not necessary promote colour innovation. There are remarkably few new colours being introduced between 1733 and 1761, instead the same colours disappear and re-occur. It is of course an open question to which extent this lack of change was the result of how the wholesale trade was organised, how the silk was sold on at the company auctions in multi-coloured lots, or to which extent it reflected on how the Eurasian silk trade was organised in Canton, with few contacts surfaces between producers, Chinese weavers, and traders, European supercargoes. Consumer demand and domestic impact What about consumer demand then? Here the Scandinavian sources provide very little information, at least of what I found so far. Where the bulk of the Swedish silk was consumed is still an open question. Statistic I compiled over the numbers of pieces imported by the Swedish company, excluding smaller and very cheap pieces such as Pelongs and silk handkerchiefs, shows that the ban on domestic import instituted by the Swedish state in 1754, affected the trade negatively. 10 Graph 4. Silk pieces put up for sale in Gothenburg by the Swedish East India Company 1733 to 1759 (130 000 pieces excluding smaller pieces and readymade clothes) Source: Försäljningskataloger (Sales catalogues), vol. 1-21 (1733-1759), Enskilda arkiv inom Kommerskollegium, Ostindiska kompaniet, Kommerskollegiums arkiv, RA, Stockholm. The import of silk for re-export was not banned, which explain the increase in the late 1750s (marked by the red circle in Graph 4). The growing silk import then does probably reflect the effect of the Seven Year War on the price of Bohea tea, the most important goods imported by the Scandinavian companies. With less competition there price of Black tea went down, something that allowed the Scandinavian supercargoes to invest more in Silk. There seemed also to have been more credit available on the Canton market, making it cheaper to borrow money with which to purchase Chinese goods for, particularly for companies based in small neutral countries like Denmark and Sweden. Nonetheless, the regulation of 1754 as well as earlier import regulations of specific types of silk goods, suggests that Chinese silk did find a market in Sweden. Unfortunately I have found very little material with which help we can trace the domestic end of this trade. The political debate concerning the restrictions on Chinese silk can help us a bit on the way. The privileges of the Swedish company, and particularly its trade in silk textiles evoked opposition among representatives for Swedish manufacturers, and particularly those involved in textile production and retail. The discussion followed patterns familiar from other European countries, the company and the import from China was pitched against the progress of domestic industries. Those critical against the trade with China said it undermined the Swedish industry; Sweden should be exporting not importing silk. Those in favour of the Swedish company said that Chinese silk filled a gap in the market, arguing that Swedish silk manufacturing was mainly targeting the top end of the market. French and Italian silk was the main competitor here, not Chinese silk, the cheapness of which allowed it to be bought by less well-off consumers otherwise excluded from the market. Moreover, it was claimed that Swedish silk manufacturers were not able to produce enough to keep domestic consumers provided with 11 textiles. To which extent the defenders of the company were right is of course hard to say. But the argument that Chinese silk textiles were largely supplying a segment of the market that could not afford the Swedish or the continentally produced silk textiles was repeated in responses from staple towns and municipals asked to comment on the effect of the East India trade in Sweden in conjunction to the renewal of the charter in 1746.13 While Chinese silk textiles might have penetrated the Swedish market, it is important to underline what was stated in the beginning of this paper, that generally speaking Sweden, together with the rest of northern Scandinavia, i.e. Norway and Finland, was not a scene for a Consumer Revolution similar to what took place in Britain, the Dutch Republic of France in the eighteenth-century. This does of course not mean that Asian or for that matter Continental material culture failed to make an impact in other respects. Taking colours as a cue we can trace some of the effects of Asian textiles in Swedish handbooks and advice literature on dyeing. One of the most significant Swedish contributions to this genre is the work of Johan Linder (16781724) later ennobled Lindestolpe. Linder was a physician with a keen interest in natural history and dyes, as is demonstrated in his Swedish Art of Dyeing. With Domestic Herbs, Gras, Flower, Leaves, Barks, Rots, Plants, and Minerals, first edition published 1720.14 Albeit writing in Swedish Linder’ approach was a global one. After discussing the historical use of colours, largely drawing on antique authors and the Bible, genres with a distinct European and Christian scope, Linder moved on to trade and manufacturing in a discussion that spanned the globe. Under the subheading “On Blue Colour” we learn the vernacular Philippine, Indian, Chinese, and Mexican names for Indigo, as well of the six different types of Indigo from the East Indies (Biana, Circhees, Jamboeser, Caromanel, Javane, och Souratte), and high and low quality Indigo from the West Indies (Quadimalo, Lauro versus Caribis, Platto, Xerquies, and Domingo).15 From globally sourced raw material to Parisian dye works Linder linked plants, insects and minerals to a rich colour nomenclature reflecting a personal intimacy with the material culture of eighteenth century Europe; Linder had spent a considerable amount of time studying on the Continent. Some names we recognise from the East India trade, such as Crimson, Incarnat, Ponceau, Bleu Turquin, Skye blue, and Bleumerant but here are many more that by all accounts never entered the China trade.16 This rich colour backdrop forms the starting point for what is the main purpose of Lindér’s book, to promote the use of dyes made of domestic material. Following his historical and global introduction to the colour red, which includes a section on where to source the best Brazilwood (in the region of Fernambuco, Brazil), and how it was processed in dye works in Amsterdam, Linder 13 On this discussion see Thomas Magnusson, ”… till Rikets Obeoteliga Skada och deras Winning…”: Konflikten om Ostindiska Kompaniet 1730-1747. 14 Swenska Färge-konst, Med inländska Örter, Gräs, Blommor, Blad, Löf, Barkar, Rötter, Wäxter och Mineralier (Stockholm, printed by Johan Laur. Horrn, kongl. antiquit. archivi boktr., 1720). On Lindestolpe see George Gezelius, Försök til et biographiskt Lexicon öfver Namnkunnige och lärde Svenske Män, Andra delen, I-R (Stockholm, printed by hos Joh. A. Carlbohm, 1779) pp. 127-128. 15 Linder p 54 16 Linder, see e.g pp. 38, 39, 60, 66. 12 concludes: 17 “This said on foreign red colours. Let us now see if also in our country there is something to be used to the same effect.”18 Blueberries, juniper berries, elderflower berries, cherries, plumbs but also moss, nettles, and black alder were some of the ingredients in listed as alternatives to the goods from Asia and the Atlantic world.19 Not only does Linder display an intimate knowledge of a North European landscape, bio topical information are often included, drawing on his knowledge of natural history (a core subject in early modern medical education) he also identifies the material with a scientific and vernacular nomenclatures. The source of “high red” could be found “under hassle trees, in the shadow” where True Lover’s Knot (“Trollbär”) or “Herba Paris” (today, Paris quadrifolia) grew.20 Linder also outlines methods and recipes for producing dyes suitable for different mediums, however here he becomes much more general. The shades of colour Linder’s Swedish recipes would produce are commonly referred to as blue, yellow, and red, sometimes “high red” and “pale red”.21 There are exceptions, Safflower (Carthamus tinctorius) could be used to produce Couleur de Chair, and the colour of Cinnamon could be had from moss, while sot was recommended for coffee shaded socks, and verdigris for Celadon.22 What is maybe even more striking is the limited media in Linder’s account; the fibres Linder gives advice on how to colour are almost exclusively made from wool and flax in the form of pieces, yarn and threads. If we include Linder’s section on how to remove stains there are only two references to silk in his book.23 In other words, the globally produced, and continentally fashioned colour scheme Linder sought to replicate with home sourced products in the 1720s did not only lack in variation and differentiation, the media on which to projected it was also limited to the most common fibres in early eighteenth-century Swedish households. Linder was aware of this shortcoming in terms of colour variation but he suggested they would do “for those who live on the countryside”.24 He did envision improved results, completeness”, with time and if enough interests was redirected from “foreign things” to “Swedish grass and herbs”. His negligence of other material than those “made by Swedish wool and Swedish linen, spun by our women” was by all account more deliberate, it was materials he preferred to that “spun by silk worms” originating in “India, Persia, Turkey, Spain, France, Germany, England, and Holland.”25 The colours were maybe not perfect or but good enough for a European periphery, who could ill afford neither exotic dye stuff nor exotic fibres was Linder’s message. Most other books on dyeing published in Sweden throughout the eighteenth-century were geographically and politically more vague. To a certain extent this was determined by the market for this type of literature, advice books on dyeing were regularly translated from English or France to 17 Linder pp. 29, 38. Linder p. 39 19 Linder, pp. 33, 49, 61, 63, 66, 82, 83. 20 Linder p. 44 21 Linder pp. 44 45 22 Linder pp. 44, 49. 50, 100 23 Linder pp. 87, 113 24 Linder p. 39 25 Linder p. 1 18 13 Swedish.26 This was not surprising, many of the same ingredients, e.g. pot ash and fortified water, were used across Europe. Likewise the habitats of many plants and insects used to produce dye, crossed national boundaries. In addition to the general access to globally sourced dye goods, brought to Amsterdam and London and then re-exported across the continent, it is not surprising the advice literature on dyeing was such a transnational genre. Linder’s distinct Swedish approach, emanating from an inventory of the Nordic flora and fauna, was however and not surprisingly replicated in Linnaeus and his student’s writing. Linnaeus took a keen interest in the source of colours himself, on journeys across Sweden he noted down the use of domestic plants for colour production. As did many of his students, including for example Pehr Kalm (1716-1779) more famous for his journey to North America in the late 1740s. Linnaeus and Kalm both published extracts from their observations in the Annuals of the Royal Swedish Academy of Science. In 1745, two years before he set out west Kalm published “List of some domestic colour grass”, discussing local methods and sources for colours, including using blueberries to dye socks violet he encountered on a domestic journey.27 Starting his account Kalm refers to both Linder and Linnaeus, the latter had only a few years earlier published “List, of the colour grass, used on Gotland and Öland” in the same forum with the aim to improve the methods of “the uneducated peasantry”28. Notable in both Kalm and Linnaeus’ accounts is the continued exclusive focus on dyes for yarn and piece goods made from linen and wool. Another similarity with Linder’s work is the colour vagueness; the shades the different dyes resulted in are described in an undifferentiated manner, as red, blue, green. There are exceptions, e.g. the bark of apple trees, grown on the Baltic Island of Öland produced “a rather beautiful Lemon yellow” Linnaeus concluded 1742.29 The Annuals of the Swedish Academy of Science continued to publish work on colours, dyes and pigments through the cause the second half the eighteenth-century. Notable is a growing interest in the chemical production of dye following in the wake of Prussian, or Berlin blue the first synthetic dye. There are also pieces advising on agricultural methods for producing Madder (Rubia tinctorium) written by the student of Linnaeus, Eric Liedbeck (1724-1803). It is only towards the end of the century, in the work by Johan Peter Westring (1753-1833), that a notable change takes place. Like several other naturalists who belonged to Linneus’s last generation of students, Westring, a provincial physician in Norrköping, came to pay particular attention to lichen, a group of speices notoriously hard to classify using Linnaeus’ sexual system; together with fungi and algae they made up the main content of the miscellaneous class 24. The most prominent Lichen naturalists, Eric Archarius (1757-1819), a district physician in the neighbouring town of Vadstena, was a close collaborator to Westring. Drawing on his work Westring discussed the taxonomy of different lichen species, their habitats and use as a medicinal, food, and, his main focus of attention, as dyes. 26 See e.g. Kårt och redig undervisning om Färgekonsten, som lärer. At sätta aeelhanda färgor på Siden, Ylle, och Linnetyger, jämte en liten tillökning om åtskilliga färgor på hår. Det allmänna Bästa til tjenst och nytta ifrån Ängelskan öfwersatt, Salvius, Stockholm, 1747, and Fullständgi Fruentimmers Färge-Bok, jämte åtsilliga Oeconomiska försök och Konster til Fläckars uttande, Skins färgande, Lacks tilwärckande, med mera. Ifrån Danska Öfwersatt, från Hellot och med någon tilökning förbättrad på en bekostnad utgifwen af Carl Gustaf Berling, Lund, 1772. 27 Kalm Pehr “Förteckning på någre Ihemska Färgegräs” KVA Handlingar, 1745, p. 247 28 Linné, ”Företeckning af de färgegräs, som brukas på Gotland och Öland” KVA Handlingar, 1742, p. 20. 29 Linné, ibid, p. 26. 14 A piece published in the Annuals of the Swedish Academy of Science (all in all seven sections occurring between 1791 and 1798) outlines the results of hundreds of experiments dyeing with lichen. Westring also produced a series of eight booklets with the joint title The Colour History of Swedish Lichen, or how to use them for colouring and in other useful ways for the household, in the first decade of the nineteenth century. Judging by the response to Westring’s second series his audience was in part made up by (critical) chemists.30 However, next to the scientific community it is clear from Westring’s writing that he had two other extra scientific audiences in mind, those working in the dyeing trade and “curious Swedish Ladies”.31 And to these groups Westring had a lot of variations to offer. Take for example shades belonging to the category brown. Compared to the vague nomenclature used in the sales catalogues of the Swedish East India Company, were silk textiles frequently were described as being “Brown varied” Westring offered much more distinct brown variations. In addition to “Noisette”, “Chestnut” and “Oak bark brown”32 we find a wide range of more exotic colour references including not only chocolate brown but “dim Choclade au lait” 33and “Choclad de Santa “,34 two types of tobacco brown, Tabac de Vénise 35 and Tabac d’Espagne.36 Next to Cinnamon brown37, we find references “Nutmeg”38 and “Rhubarb brown”39. Westring’s recipes would also produce colours such as “Terre d’ Egypte”, described as a ”grey brown beautiful” shade,40 and “Mumie” a “dark grey brown”.41 As the examples above illustrate, the nomenclature was largely French in origin, Westring use “Poil de veaus” as a synonym for “Golden brown”, 42 and “Garance foncé” for “Dark yellow brown”43. Finally, among the many colours that could be applied on silk using Mountain Saffron, today Solorina crocea, then Lichen Corceu, as the distinctive ingredient we also find a grey brown Westring labels “Thé au lait”.44 As we learned from above, the name “tea colour”, referring to a clear yellow tinted shade reminiscent of tea made of Hyson or other green tea types, was used in instructions for Chinese silk manufacturing and could also be found in material relating to smuggling. It did however not penetrate the Eurasian silk trade beyond Canton. But, as Westring exemplify, tea as a colour reference did nonetheless travel across the Eurasian continent, from China to Sweden. Not surprisingly, since tea became such a popular beverage in Europe, but not of course in its green version. “Thé au lait” refers to a shade reminiscent of milky black tea, which was the most popular way of having tea in Europe. Moreover, although Britain was the number one tea drinking nation in Europe this colour term is not English in origin but French, the dominating language of fashion. 30 Westring, Booklet 1, volume 7, no page. Westring, Booklet, 1, volume 1. p. XV. 32 Westring, Booklet 2, volume 1, p. 18. 33 Westring, Booklet, ?, volume 5, p. 202. 34 Westring, Booklet 1, volume 6, p 218. 35 Westring, Booklet 1, volume, 3, p. 90. 36 Westring, Booklet, 1, volume 7, p 194. 37 Westring, Booklet 1, volume 2, p. 36. 38 Westring, Booklet ?, volume ?, p. 121. 39 Westring, Booklet 1, volume 2, p. 28. 40 Westring, Booklet 1, volume 2, p. 12 41 Westring, Booklet, ?, volume 5, p. 201. 42 Westring, Booklet 1, volume 3 p. 79. 43 Westring, Booklet 1, volume 3 p. 106. 44 Westring, Booklet 1, volume 3 p 107. 31 15 While Westring’s perception of tea colour was distinctly European, his understanding of the medium, silk and how it took to dye, was influenced by his experience of Chinese silk. Comparing his results with colours on silk dyed elsewhere Westring singles out Asian produce particularly, claiming his colours “achieved the same firmness and shine as the Chinese”.45 Together with numerous references to cotton, Westring’s book also reflects on the broadening use of different textile in Sweden. Wool and linen are no longer the only fibres discussed as mediums for colours, silk and cotton are also frequently listed in the recipes. Lichen by all account was a dye matter that could be used both on new and old fibres, made from animal and plant material. *** Placing information on the silk trade in Canton, next to statics on import of Chinese poesis damask to Sweden, and discussion on dyes and colours among Swedish naturalists suggest a complex global movement of dyestuff, dyed fibres, colours and colour references, where material and immaterial cultures became separated along the way and then re-united albeit in new constellations. While the Chinese “Tea colour” failed follow the silk goods from Canton to Europe lichen growing above the polar circle, in the Swedish Lappmarken and Finish Österbotten could be drawn on to produce “Thé au lait” coloured silk, a name that linked Chinese black tea, taken in the European way with milk, to the centre of European fashion. It is possible to detect changes over time studying variations in the colour nomenclature; between Linder in 1720 and Westring in the 1790s, the number of colours naturalists thought was possible to extract from plants and other local resources domestic to Sweden increased greatly. It is as if by the end of the eighteenth-century a match has been established, between the colour culture in Europe, and the colours possible to replicate with domestic dyestuff. It might even be possible to argue that the works of Linder and Westring illustrate the growth of the consumption of cotton and silk fibres in Sweden. These observations suggest that Sweden was moving into a consumer culture similar to what can be found on the continent, in the North West of Europe. On the basis of what we can find out about the import of Chinese textiles from the first half of the eighteenth-century we could perhaps argue that the many thousands of brightly coloured pieces of Chinese produced damask, satin, and taffeta imported before 1754 paved the way for this development; that they helped to establish colour reference and fibre preferences in the Swedish society enlarge. Chinese silk was after all cheap and popular among groups who could not afford Swedish or continental silk, at least if we are to believe those in Sweden who argued in favour of allowing the Swedish company to continue supplying the domestic market. However, it is not clear that the silk that was imported from China to Sweden reflected demands voiced by Swedish consumers, at least not in terms of colours. As the analysis of the poesis damask import illustrates, the variety of colours on the Chinese silk was somewhat static particularly for a quality that were used for clothing and hence sensitive to more rapidly changing fashions. Of course there were changes to the colour composition of the annual cargo of poesis damask; Crimson coloured pieces became more common while the proportion of Sky Blue coloured pieces declined, but there were few new colours introduced. There is little evidence of innovation, something that might reflect on how the trade was organized in Canton, in the contact zone inhabited by Chinese merchants and European supercargoes but where manufacturers of silk or silk merchants with large 45 Westring, Booklet, 1, volume 1. p. VII. 16 stocks seemed to have been absent. It could also reflect on the status of silk in Europe. While there was no equivalent to the cotton textiles from India, painted and printed in colour fast dyes, in Europe there was a strong silk industry which generated its own fashion and trends on an annual basis. It meant that in contrast to Indian cotton textiles Chinese silk did generate product innovation and import substitutions in Europe, and competition from Europe. Then of course it was also the time it took to shift the goods from China to Europe, a delay that should have prevented Chinese silk from interrupting more actively in the annually changing trends to European silk fashion. Judging by the responses to the Chinese silk in Sweden the import from China supplied the low end of an existing market, a market in which French and Swedish produced silk provided the top end. Maybe the lack of variation in the Swedish import of Chinese silk reflects both on its subordinated position in relation to particularly the French produced silk, but also perhaps on the in-experience of its Swedish consumers?