Document 13206908

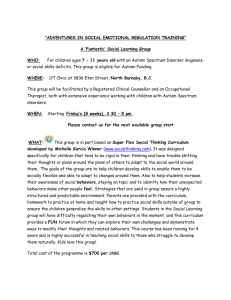

advertisement