AN ABSTRACT OF THE RESEARCH PAPER OF

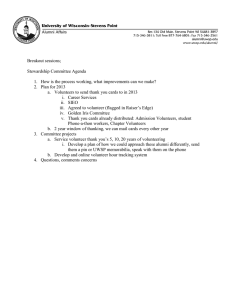

advertisement