A Marine Resource Management Internship Report Internship served with:

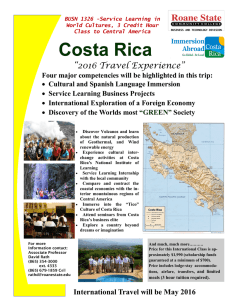

advertisement