This article was downloaded by:[Ingenta Content Distribution] On: 20 January 2008

advertisement

![This article was downloaded by:[Ingenta Content Distribution] On: 20 January 2008](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/013203904_1-97dbb0dfc0611a65bfdba9b10ec0b828-768x994.png)

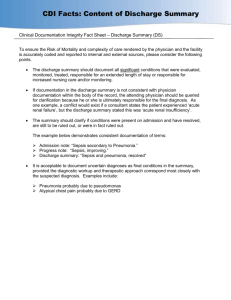

This article was downloaded by:[Ingenta Content Distribution] On: 20 January 2008 Access Details: [subscription number 768420433] Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Aging & Mental Health Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713404778 Delayed discharge - a solvable problem? The place of intermediate care in mental health care of older people J. M. Paton a; M. A. Fahy a; G. A. Livingston a a University College London, Department of Psychiatry, London, UK Online Publication Date: 01 January 2004 To cite this Article: Paton, J. M., Fahy, M. A. and Livingston, G. A. (2004) 'Delayed discharge - a solvable problem? The place of intermediate care in mental health care of older people', Aging & Mental Health, 8:1, 34 - 39 To link to this article: DOI: 10.1080/13607860310001613310 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13607860310001613310 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article maybe used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. Downloaded By: [Ingenta Content Distribution] At: 17:51 20 January 2008 Aging & Mental Health, January 2004; 8(1): 34–39 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Delayed discharge—a solvable problem? The place of intermediate care in mental health care of older people J. M. PATON, M. A. FAHY & G. A. LIVINGSTON University College London, Department of Psychiatry, Highgate Hill, London, UK Abstract The National Service Framework for Older People envisages the development of intermediate care for older people. This study examined the possible role of intermediate care beds within mental health trusts. We interviewed senior clinicians in an inner city old age psychiatry service about the 91 current in-patients on the old age psychiatric wards. Sixty-five were classified as acute patients and the remaining 26 were continuing care patients. Structured instruments were used to collect information regarding neuropsychiatric symptoms, activities of daily living and current met and unmet needs. Where discharge was delayed an assessment was made regarding the appropriateness for an intermediate care setting according to the criteria set by the Department of Health guidelines. A total of 30 (46%) patients’ discharges were delayed. Of these, 19 (29%) patients met the DOH criteria for intermediate care; 10 (53%) had dementia, five (26%) affective disorder, and four (21%) with schizophrenia. The 11 other delayed discharges were because of lack of availability of finance for placements. The study found that the prompt discharge of older patients from acute psychiatric care was a significant problem and many of those patients may benefit from the therapeutic and rehabilitative process afforded by intermediate care. Introduction The National Service Framework for Older People (NSF) sets out a vision of intermediate care as a ‘vital component of the programme to improve the health and well-being of older people and raise the quality of services they receive’ (Department of Health, 2001). Intermediate care (IC) is defined as ‘a range of integrated services to promote faster recovery from illness, prevent unnecessary acute hospital admission, support timely discharge and maximise independent living.’ The NSF recommends the establishment of IC beds within all older people’s services and generally sets a six-week upper limit for intermediate care. Government policy sees IC not as an optional extra for older peoples’ services but as central to the modernisation agenda. The government has announced its intention to create 5,000 IC beds by 2004 in a variety of settings such as hospitals, patient’s homes and nursing homes (Pollock, 2000). About 6% of patients in acute general medical wards at any one time are awaiting discharge (Robinson, 2002). There has been less research on this problem within psychiatry, although one study in older psychiatric patients found that about 40% of bed days were used for patients whose discharge had been delayed (Draper & Luscombe, 1998). The mental health of older adult in-patients often improves while in an acute psychiatric ward but may, however, remain at a level such that patients continue to require significant help while no longer needing to be in an acute psychiatric ward. It might be expected that IC would be appropriate in these circumstances. Yet within mental health care for older people there is currently no alternative to acute admission beds other than community treatment, respite care or long-term 24-hour care. While there are IC schemes for older patients with physical illnesses, IC for older psychiatric patients is uncharted territory, as the schemes have not been piloted in mental health. The research base for IC is limited and confined to physical health. What research there is shows overall patient and carer satisfaction and a moderate reduction in admissions and delayed discharge. There may be difficulties with the IC model; for example, the somewhat arbitrary time limit of six weeks and the new suggested role of primary care in established physical services is proving problematic. After six weeks of intensive rehabilitation and service provision the general practitioner (GP) is then left to continue care often with increased expectation of Correspondence to: Joni M. Paton, University College London, Department of Psychiatry, Holborn Union Building, Highgate Hill, London, N19 5LW, UK. Tel: þ44 (0) 207 288 5931. Fax: þ44 (0) 207 288 3411. E-mail: j.paton@ucl.ac.uk Received for publication 29th November 2002. Accepted 4th May 2003. ISSN 1360-7863 print/ISSN 1364-6915 online/04/01034–06 ß Taylor & Francis Ltd DOI: 10.1080/13607860310001613310 Downloaded By: [Ingenta Content Distribution] At: 17:51 20 January 2008 Delayed discharge—a solvable problem? 35 Aim The aim of IC is to provide integrated services to promote faster recovery from illness, prevent unnecessary acute hospital admissions, support timely discharge and maximise independent living. Standard The standard is that older people will have access to a new range of IC services at home or in designated care settings, to promote their independence by providing enhanced services from the NHS and councils to prevent unnecessary hospital admission and effective rehabilitation services to enable early discharge from hospital and to prevent premature or unnecessary admission to long term residential care. Intermediate care services should: • Be targeted • Be provided on the basis of comprehensive assessment • Be designed to maximise independence • Involve short-term interventions • Involve cross-professional working • Be integrated within a whole system of care Intermediate services should: • Havecare an upper limit of time spent there of six weeks FIG. 1. three). Summary of NSF intermediate care standard. The aim and the standard of IC is outlined in the NSF (standard what can be provided. Intermediate care comes under the remit of general medical services (GMS) and GPs are not paid extra for GMS. MacMahon (2001) argues that although minimising the duration of hospital stays by older people is important, he warns against the risk of IC ‘being used as a euphemism for indeterminate neglect’. Intermediate care could be a way of making older people’s care a ghetto service, by denying them the appropriate care in mainstream services or leaving older people in a cheaper bed without solving the problems that prevent discharge, for example finding an appropriate long-term home. If the only problem preventing appropriate discharge is funding by the cash-strapped social care system, it is important that patients are not left in an intermediate care bed instead of a permanent home. It is also not an alternative to the well-established community mental health teams that provide home treatment. The current study considers the role of intermediate care for older psychiatric patients by assessing, firstly whether in-patients in an inner London mental health and social care trust were being cared for in the appropriate setting. Secondly, we considered if patients who were not in the appropriate setting would meet the criteria for an intermediate care bed (see Figure 1). Methods The setting The study took place in a NHS mental health and social care trust, which serves a deprived inner-city area with a population of about 500,000 people. The interview A research psychologist (JP) interviewed doctors and senior nurses regarding each patient on all of the older adult psychiatric wards in the Trust and administered a battery of standardised instruments and attended eligibility panel meetings. The research psychologist (JP) recorded the number of days since admission, and whether the patient was recorded as a ‘delayed discharge’. The definition of delayed discharge within the Trust was the period that started on the day when the consultant in the context of a multi-disciplinary team review had decided that the patient was ready for discharge. Instruments The Camberwell Assessment of Need for the Elderly (CANE). This was administered by the research psychologist (JP) who gained information from professional staff. She discussed her ratings with the other two authors, who are both experienced clinicians and researchers, to ensure that the data was scored reliably. The CANE measures the number of met and unmet needs in older people according to patient, carer and staff report (Reynolds et al., 2000). It has good content, construct and consensual validity. It also demonstrates appropriate criterion validity. Reliability is generally very high: kappa > 0.85 for all staff ratings of inter-rater reliability. Correlations of inter-rater and test-retest reliability of total numbers of needs identified by staff were 0.99 and 0.93, respectively. Unmet needs score as two, and no needs as zero, met needs as one. A met need is when an individual has difficulty but Downloaded By: [Ingenta Content Distribution] At: 17:51 20 January 2008 36 J. M. Paton et al. the difficulty is being provided for. An unmet need is again regarded as an area when there is a difficulty but the individual is not receiving the appropriate level of assessment or treatment. The needs assessment covered the following items: accommodation, looking after the home, food, self-care, caring for someone else, daytime activities, memory, eyesight/hearing, mobility, continence, physical health, drugs, psychotic symptoms, psychological distress, information, deliberate self-harm, accidental selfharm, abuse/neglect, behaviour, alcohol, company, intimate relationships, and money and benefits. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI). Cummings et al. (1994) scores both frequency and severity of a range of psychiatric symptoms other than memory for patients (e.g. hallucinations, aggression, depression) with dementia and other neurological illnesses. There are 14 symptom areas covered. Possible scores range from 0–144 and is reached by multiplying frequency by severity of individual items and adding them together. Higher scores indicate increased severity. It has good content and concurrent validity as well as inter-rater and test-retest reliability. Cummings and his colleagues (1994) tested a 10-item version of this instrument in a control population (older people without psychopathology) and in people with dementia attending out-patients. The mean scores were respectively 0.43 and 8.25. The mean NPI score in a previous study of the same continuing care wards as in this study was 10.4 (Fahy & Livingston, 2001) The Abbreviated Bristol Activities of Daily Living Scale. (The Bristol ADL: Bucks et al., 1996) is divided into two domains: (1) instrumental activities (food, eating, drink, communication, telephone, housework, shopping) and (2) self care (drinking, dressing, hygiene, teeth, bath/shower, toilet/commode). A higher score indicates increasing dependency. Possible scores range from 0–39. If an item is not applicable it scores 0. For example when a patient never shopped for himself or herself because they were in a wheelchair or because their partner had always done it. It has satisfactory face validity, construct validity, and concurrent validity as well as test-retest reliability. Eligibility panel The eligibility panels meet weekly to consider appropriate placement of older people. The panel decisions are about 24-hour care settings, or care packages over a threshold financial amount, and are for all patients, whether or not the patient is financially independent. It ensures that patients needs meet eligibility criteria and so they are placed appropriately. For example, they looked closely at behavioural problems and risks and discussed how this could be managed in differing placements. There was no discussion of funding as the panel decides only eligibility. JP attended the eligibility panels to clarify the process and how decisions are made. Consultant interview JP interviewed the consultants with regard to each patient responsible. The interview covered the following questions: 1. Diagnosis—consultant diagnosis. 2. What ideally should happen to the patient in terms of discharge. 3. Are they in the optimal setting? 4. If not, why not and what would be an appropriate placement for the patient. Analysis The reasons for delayed discharge were recoded into four categories: 1. Lack of specialist staff resources for placement or returning home (encompassing not being allocated to a social worker, placement panel reports not being completed, not being presented to the placement panel, a place not being found after approval by the panel, and awaiting package of care and/or intensive clean). 2. Lack of money to finance placement for example, local service services said money was not available at present. 3. Lack of an alternative to acute ward when the patient no longer needs acute care. 4. Miscellaneous (e.g. relative or family refuses to pay for placement, or placement offered deemed unsuitable for patient or family). Results There were seven Mental Health Care of Older People (MHCOP) wards with 91 occupied beds. There were 56 patients in the acute wards and 35 in continuing care (CC). Of the patients in CC wards, nine had been placed there temporarily. They did not meet the criteria for CC and there was no intention that they remain there in the long-term. The rest of the results will focus on these 65 (56 in acute, and nine temporarily in CC) patients who were not intended to stay in hospital permanently. The mean age of patients was 76 years old, (range 63–96 years). Two patients were under 65 (3%) of whom one had depression and one had schizophrenia, and both were physically frail. Twenty-three (35%) were male, 46 (71%) were White British, Downloaded By: [Ingenta Content Distribution] At: 17:51 20 January 2008 Delayed discharge—a solvable problem? three (5%) Greek-Cypriot, five (8%) were White other, four (6%) were Black African/Caribbean and one was Asian. The most common diagnosis was dementia 26 (40%), followed by affective disorders 22 (34%), and 22 (34%) patients had enduring psychoses. There were two (3%) with personality disorder, one with a learning disability and two (3%) who had not yet received a diagnosis. The mean length of admission was 109 days (four days to 3.2 years). Patients scored highly on the both the NPI (mean ¼ 27; range ¼ 1–112) and Bristol ADL (mean ¼ 11; range ¼ 0–36). There were 30 (46%) patients whose discharges were delayed. These delayed discharges were for the following reasons: 15 (30%) insufficient specialist staff resources for placement or returning home; six (20%) lack of money to finance placement; six (20%) no alternative to acute ward when the patient no longer needs acute care. The final three (10%) delayed discharges were in the miscellaneous category (two relatives refused to pay for placement; one relative and patient turned the placement down). Following DOH guidelines, 19 (29%) candidates were suitable for IC (12 in category 1, six in category 3 and one in category 4). The group identified for IC had a median length of admission of 86 days (12 days to 3.2 years), median total NPI score of 25 (1–103), and median Bristol ADL score of 11 (0–29). The most common diagnosis was dementia (10; 53%), followed by affective disorders (5; 26%) and schizophrenia (4; 21%). The CANE identified the following unmet needs: accommodation ¼ 32 (49%), help with self-care ¼ 30 (46%), being vulnerable to abuse from others and needing additional help with looking after the home (both ¼ 26; 40%). Other frequent unmet needs were: management of risk of accidental self-harm ¼ 21 (32%), help with providing themselves with food ¼ 21 (32%). Less common unmet needs were help with memory ¼ 15 (23%), behaviour ¼ 11 (17%), continence ¼ 10 (15%), company ¼ 8 (12%), alcohol ¼ 7 (11%), daytime activities, intimate relationships and managing medication (all 9; 14%). There were relatively few unmet needs in the categories of psychological distress and deliberate self-harm both ¼ 6 (9%), money ¼ 3 (5%), mobility, benefits, caring for someone else all ¼ 2 (3%), and physical ¼ 1 and psychotic symptoms ¼ 1. The commonest unmet needs identified by the CANE for the 19 patients who met DOH IC criteria were: accommodation (16; 84%), looking after the home, needing help with self-care (both 12; 63%) and inadvertent self-harm (9; 47%). Many patients had unmet needs for help with getting enough food (8; 42%) or with managing medication, being vulnerable to abuse from others and needing help with memory (all 5; 26%). Less common unmet needs were the need for help with continence (4; 21%); difficult behaviour (3; 16%) and management of alcohol problems (2; 11%). Individuals had 37 TABLE 1. Mean number of met and unmet needs in Intermediate care and non-intermediate care groups Intermediate care Non intermediate care Mean number of met needs (SD) Mean number of unmet needs (SD) 9 (3.1) 10 (3.4) 4 (2.6) 2 (3.1) unmet mobility needs, unmet needs for intimate relationships, daytime activity, psychotic symptoms, psychological distress and company (all 1). Table 1 shows the mean number of met and unmet needs in the intermediate care and non-intermediate care groups. Wilcoxon signed ranks showed a significant difference ( p 0.05) with a higher mean number of unmet needs in the group that met DOH criteria for IC, compared to the non-intermediate care group. Discussion This study found that about 40% of patients in acute MHCOP wards were no longer in the appropriate setting. In this study, as in others, some patients who were admitted to an acute ward and return to their pre-morbid functioning were discharged without delay to their home (Moss et al., 1995; Cohen & Casimir, 1989). The patients whose discharge had been delayed remained in an acute (or occasionally continuing care) ward until, for example, their homes were adapted or cleaned, there was an increase in care package or long-term care was arranged. Not only were this group of patients not in the optimal environment but also, this environment may be positively harmful in terms of risk from other peoples’ behaviour or iatrogenic illness (Steiner, 2001), for example, patients could be harmed by an acutely disturbed patient. Most of them had been in these beds for about three months. A few had longer delays and some of these were due to family disputes, which might also affect IC settings even when other difficulties had been sorted out. The focus on sorting out discharge would however mean these problems would be prioritised. Nevertheless it would not always be realistic in mental (or physical) health to discharge all patients from IC at six weeks however well laid the plans were. There were some patients whose discharges were delayed because they no longer needed an acute admission ward but needed active rehabilitation before they went home. There were others whose homes were not suitable to go to (usually because of the patient’s extreme neglect before admission). Many patients could have benefited from active rehabilitation and increasing their daily living skills. In addition, there were patients who did not need an acute ward but needed a new place to live with 24-hour care. These placements could not be found instantaneously due to a number Downloaded By: [Ingenta Content Distribution] At: 17:51 20 January 2008 38 J. M. Paton et al. of reasons, including assessment, patient and carer preference and appropriate places were not necessarily available. This process is complex and time consuming. Those patients who had recovered enough to not need an acute ward but were not ready to be discharged home required a setting to target faster recovery from illness, support timely discharge and maximise independent living through integrated services. Some sort of step-down care to avoid the disadvantages of remaining in an acute ward was needed at this juncture. Most of these patients required 24-hour care and thus a home treatment scheme could not meet their needs, unless it provided round the clock one-to-one care. This would be an extremely expensive option and would not meet the needs of those who needed rehabilitation or whose homes were uninhabitable. Intermediate care Individuals in our study had a complex spectrum of unmet needs, for example, alcohol abuse, neuropsychiatric symptoms and psychological distress, and therefore input from all members of the multidisciplinary team would be essential. An intermediate care service where there was integrated health and social services consisting of social work, occupational therapist, psychology, nursing and medical input would be a solution. As most of these patients had high numbers of neuropsychiatric symptoms (much greater than psychiatric out-patients or those in continuing care) it would be inappropriate to place them in an IC setting which had been set up for the needs of people whose main problem was a physical illness. A dedicated psychiatric facility was therefore necessary. If the staffs’ major roles were rehabilitation, assessment for appropriate placement and finding the right setting for the patient to live, then the patients’ function would be maximised and their discharge expedited. Some of the patients whose discharge was delayed had been found suitable placements but had not moved from the acute wards, as funding was not available. They were not suitable for IC because their only need was funding which would not be provided in an IC environment and if they moved to IC, it would be in danger of becoming a parking service rather than a rehabilitative or assessment service. We have discussed our study and its findings with all the consultant psychiatrists involved in the patients care, psychologists, occupational therapists, social workers, nurses, commissioning groups and health service managers. The professionals identified a significant problem with delayed discharges and this reduced access to acute beds. Whilst IC was judged to be an appropriate solution there were concerns that IC would be used instead of placing people rapidly in an appropriate community resource. The separation of mental health and primary care trusts has increased the complexity of partnerships needed to commission such services (Herbert, 2002). The evidence in our study indicated that there were already substantial delays in discharge from the acute wards. A dedicated psychiatric IC service would aim to tackle this problem. We have however not consulted with patients and carers and think that is a necessity before final decisions are made. In addition, we have not studied the patients who might benefit from IC by prevention of an acute admission or transfer from the physical care wards where they were no longer appropriately placed. Conclusions We conclude that delayed discharge is a problem for older inpatients with mental health problems. While the British health framework and changes were what originally sparked our interest, the results have international implications with discharge, as there are similar difficulties in other countries (e.g. Draper & Luscombe, 1998). The possibility of new funding for intermediate care is an opportunity to turn this problem around. Already in some areas patients with mental health problems are excluded from IC (Baldwin, 2003). Our study indicates that this is inappropriate. It will require an initial injection of resources but should enable services to reduce excessive and inappropriate spending on acute in-patient care. Intermediate care should help the development of seamless service provision. These new services will require evaluation. Intermediate care will not be a panacea and has potential problems but seems a better solution than the present system. References BALDWIN, R.C. (2003). National Service Framework for older people (editorial). Psychiatric Bulletin, 27, 121–122. BUCKS, R.S., ASHWORTH, D.L., WILCOCK, G.K. & SIEGFRIED, K. (1996). Assessment of activities of daily living in dementia: development of the Bristol activities of daily living scale. Age and Ageing, 25, 113–120. COHEN, C.I. & CASIMIR, G.J. (1989). Factors associated with increased hospital stay by elderly psychiatric patients. Hospital Community Psychiatry, 40, 741–743. CUMMINGS, J.L., MEGA, M., GRAY, K., et al. (1994). The neuropsychiatric inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology, 44, 2308–2314. Department of Health. (2001). The National Service Framework for Older People. London Stationary Office. Available at http://www.doh.gov.uk/nsf/olderpeople.htm DRAPER, B. & LUSCOMBE, G. (1998). Quantification of factors contributing to length of stay in an acute psychogeriatric ward. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 13, 1–7. FAHY, M. & Livingston, G. (2001). The needs and mental health of older people in residential placements. Aging & Mental Health, 5, 253–257. Downloaded By: [Ingenta Content Distribution] At: 17:51 20 January 2008 Delayed discharge—a solvable problem? HERBERT, G. (2002). Exclusivity or exclusion: meeting mental health needs in intermediate carer. Nuffield Institute for health. MACMAHON, D. (2001). Intermediate care—a challenge to specialty of geriatric medicine or its renaissance? Age and Ageing, 30, 19–23. MOSS, F., WILSON, B., HARRIGAN, S. & AMES, D. (1995). Psychiatric diagnoses, outcomes and lengths of stay of patients admitted to an acute psychogeriatric unit. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 10, 849–854. PHELAN, M., SLADE, M., THORNICROFT, G., et al. (1995). The Camberwell assessment of needs: the validity and reliability of an instrument to assess the needs of people 39 with severe mental illness. British Journal of Psychiatry, 167, 589–595. POLLOCK, A.M. (2000). Will intermediate care be the undoing of the NHS? British Medical Journal Clinical Research Edition, 321, 393–394. STEINER, A. (2001). Intermediate care—a good thing? Age and Ageing, 30, 33–39. REYNOLDS, T., THORNICROFT, G., ABAS, M. et al. (2000). Camberwell Assessment of Need for the Elderly (CANE). Development, validity and reliability. British Journal of Psychiatry, 176, 444–453. ROBINSON, J. (2002). Bed-blocking. Discharge of the late brigade. Health Service Journal, 112, 22–24.