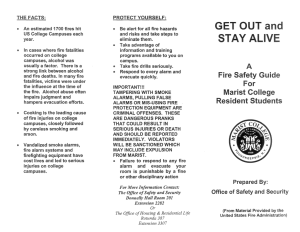

Guide to Teaching Fire Safety

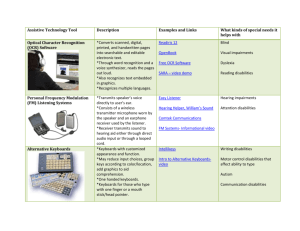

advertisement