ABSTRACT USING ART AS A METHOD ... IN A KINDERGARTEN SERVICE-LEARNING PROJECT

advertisement

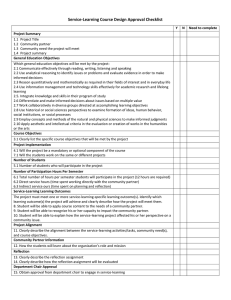

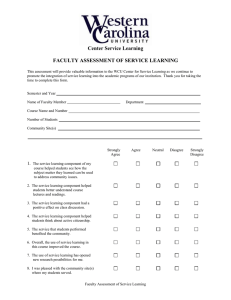

ABSTRACT USING ART AS A METHOD OF CRITICAL REFLECTION IN A KINDERGARTEN SERVICE-LEARNING PROJECT Creating artwork can be a bridge for students to relate to what they are learning and connect it to their own experiences. This study adds to the body of literature on the importance of integrating the arts into the core curriculum as a way of promoting critical thinking and reflection. Using a convergent parallel mixed methods, this study explored the use of art as a method of critical reflection for kindergarteners participating in a service-learning project. This research project was implemented in two cycles at different private schools in northern California. Quantitative data was collected through analysis of student work and checklists. Qualitative data in the form of observation notes, recorded discussions, and photos was collected and analyzed using triangulation techniques. Although conducted on a small scale, this research study found that arts integration led to higher levels of student engagement, more student participation, and deeper levels of reflection. Nicole Schoentag December 2012 USING ART AS A METHOD OF CRITICAL REFLECTION IN A KINDERGARTEN SERVICE LEARNING PROJECT by Nicole Stephanie Schoentag A project submitted to Dr. Melanie Wenrick in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Teaching in the Kremen School of Education and Human Development California State University, Fresno December 2012 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . iv LIST OF FIGURES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . v 1. EXPLORING ARTS INTEGRATION AND SERVICE LEARNING FOR KINDERGARTEN . . . . . . . . . . . . 1 Chapter Purpose . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2 Literature Review . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3 Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8 2. RESEARCH DESIGN FOR CYCLE 1 AND CYCLE 2 . . . . 9 . Service-Learning Units . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11 Quantitative Data . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13 Qualitative Data . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14 Validity and Reliability . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14 3. ACTION RESEARCH RESULTS . . . . . . . . . . 16 Quantitative Results for Cycle 1 and 2. . . . . . . . . 16 Qualitative Results for Cycle 1 . . . . . . . . . . . 22 Qualitative Results for Cycle 2 . . . . . . . . . . . 26 4. DISCUSSION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31 Comparison of Results . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31 Implications for Teaching . . . . . . . . . . . . 35 Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37 REFERENCES. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 39 APPENDICES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41 A. RUBRIC USED FOR ANALYZING ARTISTIC REFLECTIONS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .41 iii B. SAMPLE OF ENGAGEMENT CHECKLIST. . . . . . C. CALIFORNIA STANDARDS ADDRESSED BY UNITS . . 42 . . 43 D. STUDENT WORK SAMPLE . . . . . . . . . . . . 44 E. STUDENT WORK SAMPLE . . . . . . . . . . . 45 iv LIST OF TABLES Table Page 1. Data Used for Paired T-Test in Cycle 1 . . . . . . . . . 17 2. Data Used for Paired T-Test in Cycle 2 . . . . . . . . . 17 3. Data Used for ANOVA in Cycle 1 . . . . . . . . . . 19 4. Data Used for ANOVA in Cycle 2 . . . . . . . . . . 19 5. Data Used for Chi Square in Cycle 1 . . . . . . . . . 20 6. Data Used for Chi Square in Cycle 2 . . . . . . . . . 21 v LIST OF FIGURES Figure Page 1. Student building with recycled materials . . . . . . . . 23 2. Students watering plants on the yard . . . . . . . . 24 3. Students painting recycled materials to build sets for their play . . 25 4. Students engaged in small group discussions at their tables . . . 28 5. Student counting seeds inside kiwi . . . . . . . 29 6. Students planting vegetables in the community garden . . . . 30 7. Bloom’s taxonomy . . . . 33 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Chapter 1 Exploring Arts Integration and Service Learning for Kindergarten As a kindergarten teacher, I am overwhelmed by the creativity of my students. This creativity, however, is impeded by their developmental state. Many of my students have complex ideas that they would like to express; however their developing literacy skills do not allow them to use words and sentences to convey these ideas on paper. Because beginning kindergarteners do not yet have strong phonemic awareness, their creative ideas are often cut short because they opt to write words that are easier or words they have already learned instead of the ideas and stories they are truly developing in their minds. Many kindergarteners love to share orally, even though some students are intimidated by sharing their ideas in front of their peers or cannot focus for long enough for everyone to share their ideas. Art has always been a passion for me, and I want to learn more about how to integrate art into core curriculum. Having grown up in a family of artists, fine art has always gone hand-in-hand with my writing and my processing of ideas. As a teacher, my passion for art has united with my enthusiasm for teaching. One of the primary reasons I obtained both a multiple subject credential and a single subject credential in art was to learn how to better integrate the arts into core subjects. In researching these topics, I found that the arts could also be a method of fostering social and emotional growth in students. Many articles discussed how 2 creating artwork can be a bridge for students to relate to the material they are learning and connect it to their own experiences. In early childhood, students often use drawing as a springboard for social interaction (Soundy & Drucker, 2010). I also found that the research specifically on kindergarteners is rather sparse. While there is much discussion about kindergarten literacy and the benefits of arts integration, these discussions are not backed up by in-classroom research or case studies. For example, an article by Behymer explains, “Many kids find drawing to be a safe way to create symbolic representations of what they want to say, what stories they want to tell” (p. 85). Even though Behymer states that drawings are an important method of pre-writing organization for Writer’s Workshop, this information has not been tested. This study builds upon the research by creating an action research project that is grounded in these theories. My research will focus specifically on my two kindergarten classes, their engagement, and their reflections. Purpose I conducted this study because there is a lack of research focusing specifically on using art as a method of critical reflection with kindergarteners. I believe art is an integral aspect of education; however, with continued budget cuts to the arts, it is quickly being removed from American public schools. By integrating the arts into core curriculums, teachers will be able to foster creative expression and reach different types of learners while still meeting state standards for core subjects. By focusing on kindergarteners, my goal was to add to the 3 knowledge base, and hopefully, motivate more kindergarten teachers to integrate the arts into their teaching, specifically as a way of allowing for deeper critical thinking and reflection and promoting student engagement. My hypothesis was that using art as a method of critical reflection would have a positive effect on my students. I expected to see increased motivation, enhanced creative expression, and deeper levels of reflection. The objective of this research project was to test this prediction in two cycles. The first cycle was conducted from January 17 to February 8, 2012, during the winter semester of kindergarten. The second cycle was conducted from September 3 to October 31, 2012, during the fall semester of kindergarten. During both cycles, I allowed the students to reflect on their learning through both oral discussions and artistic activities at the beginning, middle, and end of the unit. I graded their reflections using a rubric (see Appendix A). I recorded levels of student engagement using an engagement checklist (see Appendix B) during both oral and artistic reflections. By using these different methods of data collection, I was able to determine if my prediction was correct. Literature Review In beginning my review of prior research, I looked at kindergarten curriculums and how arts integration affected pedagogy in that subject. It was important to me to learn about kindergarten students specifically, as their language skills are at such a particular developmental state. The research on kindergarten as a specific age range was sporadic, so I broadened my search and looked at the 4 topics of kindergarten, social learning, and integrating art into core curriculum. While the articles I read focused on kindergarteners, their research was sometimes about others interacting with kindergarteners and topics covered a wide range of subjects such as social skills development, arts integration, and collaborative work environments. Social learning. What quickly became apparent is that social and emotional learning is an integral part of any kindergarten curriculum. “The core competencies of the social and emotional learning framework include self-awareness, social awareness, self management, responsible decision making, and relationship skills” (Hutzel, Russel, & Gross, 2010, p.13). Methods to teach these competencies noted in the articles were modeling by teachers and older students at the school, and specific social skills curriculums like Strong Start (Kramer, Caldarella, Christensen, & Shatzer, 2009). Kindergarteners practice these skills as a part of their everyday interactions with each other. The Jump Start curriculum used strategies like roleplaying difficult situations before they happen and listening to stories about proper social skills as a way to provide students with the tools they need to become independent problem solvers. Social development is also enhanced through arts integration. Two articles focused on arts integration - one as a service-learning project for eighth graders (Soundy & Drucker, 2010) and the other as a teacher training method (Ofra, 2010). Both articles discussed the way creating artwork can be a bridge for 5 students to relate to the material they were learning and connect it to their own experiences. “In the early years, drawing is a highly social activity” (Soundy & Drucker, 2010, p. 447) and these projects built on the ability for art to become a mode of expression for the kindergarteners. As the kindergarteners created artwork with their eighth grade buddies, they built relationships with these older students and created pieces that related to themselves and their partner. Lastly, I explored the theme of collaborative work environments building off the idea that art is a social activity for kindergarteners and a method of selfexpression. In research by Soundy & Drucker (2010), kindergarten students were placed in groups of two or three with a pre-service teacher in each group. The students worked to create their own individual artwork as a response to the story they heard earlier. As the students completed their work, they spoke with one another and these conversations greatly influenced their work. The collaborative work environment “provided rich opportunities for participants to function as models and sounding boards for one another” (Soundy & Drucker, 2010, p.458). Kindergarten case studies. As I stated in my introduction, there were many differences in my research, as there do not seem to be very many case studies about kindergarten classes. My research covered a vast range of subjects within the common theme of kindergarten. One of the biggest problems I found in looking for and reading these articles was that while kindergarteners were participants in many of these studies, they were not always researched. For example research by Hutzel, Russel, & Gross (2010) followed eighth graders 6 working with kindergarteners to create collaborative artwork while the teacher researched the eighth graders’ social and emotional development. This article, however, failed to note the growth of the kindergarteners during this project. Research by Ofra (2010) examined the role-reversal approach, where pre-service teachers became the lead teachers and lead teachers took on more of an assistant position as the pre-service teachers implemented a interdisciplinary, project-based curriculum. This article never addressed the effects of this change on the learning of the students. Literacy and arts integration. Another problem I found in looking for articles was that while there is much discussion about kindergarten literacy and arts integration, these discussions are not supported by in-classroom research or case studies. Many of the articles I read cited other written works on the subject or pedagogical theory but lacked the element of classroom trial (references). One article explored the benefits of integrating art into an early literacy curriculum with preschool-aged children. In this article, researchers implemented the program PASELA, Promoting and Supporting Early Literacy through the Arts, which “integrated the arts into all children’s learning in all domains, and where early childhood educators and community artists creatively collaborate to ensure school readiness” (Phillips, Gorton & Sachdev, 2010, p. 111) in seven classrooms in Pennsylvania. Researchers looked to see that 80% or more of PASELA students “would demonstrate improvement in behaviors related to mastery of three of the Pennsylvania Early Learning Standards (in Language and Literacy, Creative 7 Arts, and Approaches to Learning” (Phillips et al., 2010, p. 112). They also looked to see that 80% or more of the students “would demonstrate improvements in early literacy skills, indicated by their performance on standardizes measurement instruments administered and scored by independent assessors” (Phillips et al., 2010, p. 112). This research study found “small but tantalizing improvements on literacy, learning-related, and school-readiness skills” (Phillips et al., 2010, p. 118). Although this research focuses on preschool age children, I believe the benefits of a curriculum designed with a strong focus on arts integration will benefit kindergarten age students as well. Service-learning. In searching for articles, I found much research outlining the benefits of service-learning in the classroom. Service-learning is a “teaching and learning strategy that integrates meaningful community service with instruction and reflection to enrich the learning experience, teach civic responsibility, and strengthen communities” (National Service Learning Clearinghouse, 2012) For example, the eighth graders who participated in making artwork with kindergarteners exhibited behaviors which suggested they had developed in each of the five core competencies of social and emotional learning (SKL), including self awareness, social-awareness, self-management, responsible decision-making, and relationship skills (Hutzel et al, 2010). In this article, however, the eighth graders were the participants in the service-learning project and the kindergarteners were the recipients. The benefits to the kindergarteners 8 from this project were not researched. There was no research however, that followed a service-learning project in kindergarten where the kindergarteners were the active participants in the service-learning. By giving my students the responsibility of taking on a service-learning project for themselves, I will begin to fill that area of research. Conclusion I can build upon this research by creating an action research project that is grounded in these theories. My research will focus specifically on two of my kindergarten classes, students’ engagement and participation, and the level of reflection. By implementing these theories in my classes and documenting the effects of these pedagogical techniques, I will be supplementing the already existing theoretical literature regarding arts integration with an action researchbased study 9 Chapter 2 Research Design for Cycle 1 and Cycle 2 This research project explored the use of both oral and artistic reflection in 2 different kindergarten classrooms while the students engage in a service-learning unit. Each cycle of research was implemented through units designed to be student-driven to allow their reflections to carry weight. Students’ oral and artistic reflections inspired each unit to evolve and change as it progressed. The research questions guiding this investigation were: 1. What is the process of integrating art into a Kindergarten service-learning project? 2. What impact does this have on student engagement? 3. How is depth of reflection through art related to student levels of engagement? This mixed methods study examined using art as a method of reflection while participating in a service-learning project in a kindergarten classroom. A convergent parallel mixed methods design was used. In this type of design quantitative and qualitative data are collected in parallel, analyzed separately, and then merged. Convergent parallel design prioritizes the two types of information equally. After data collection, results were analyzed looking for relationships between the two strands of data (Creswell & Clark, 2011). Participants and Context The data for this study was collected in two cycles. The first cycle focused 10 on 27 kindergarten students (15 girls, 12 boys) enrolled at a private, religious school in Sunnyvale, California where 99.47% of the students are white. The second cycle focused on 23 kindergarten students (12 girls, 11 boys) enrolled at a private, independent school in San Francisco, CA where 54% of students are white and 46% are students of color. Thirty-five percent of students enrolled at this school are on sliding scale tuition or financial aid. Critical case and convenience sampling techniques were used in this study(Onwuegbuzie & Collins, 2007). I used critical case sampling because the study focuses on kindergarten students involved in a service-learning project, and such instructional settings are unique. I used convenience sampling since this is an action research project and participants were my students (Onwuegbuzie & Collins, 2007). I also included a focus group of 10 students in each cycle. I sampled this group by selecting confirming and disconfirming cases. I looked for students who would either followed patterns emerging in my research or who did not fit into the emergent patterns. This method allowed me to add depth to the emerging patterns while evaluating rival explanations. Using this focus group allowed for a chance to gain in-depth knowledge and observations about their level of engagement. Prior to beginning the study, I introduced the research project to my students. This introduction provided all students with an explanation of the study and what their roles would be. I discussed the voluntary nature of participation, the right to withdraw at any time, and the confidentiality of the information gathered. I 11 explained to the students that they could withdraw from this study by telling me that they do not wish to continue. A letter was sent home to parents describing the study with a parental informed consent form to be signed. Students also signed an assent form that was read aloud and explained to them. To ensure the confidentiality of participants, one copy of the forms was given to participants and the other copy was filed securely in a locked file cabinet in my classroom. In addition, all participants were assigned a number that was known only to the researcher. Because service-learning was an established component of the kindergarten curriculum in both cycles, there were no anticipated risks associated with this study. However, by taking part in this study, students built their critical thinking and literacy skills. Also, by participating in this study, I learned key instructional strategies that improved my professional development related to my approach to teaching of reading, writing, and service-learning in the classroom. Service-Learning Units Research was conducted as students were participating in a service-learning project. The service-learning project for Cycle 1 addressed this essential question: “Pollution is a growing problem in the bay area. What can our kindergarten class do to help change the factors that cause pollution in the bay area?” The purpose of this project was for students to learn about the community and specifically the issue of pollution in the area, while following the California state standards for science, math, and language arts in kindergarten (see Appendix C). 12 This first unit was conducted over a three-week period in the spring semester. Over the course of the project, students responded to both fiction and non-fiction children’s literature on the subject, participated in a classroom visit from the Sunnyvale Water Treatment Center, and conducted site visits to observe local polluted areas and the effects of pollution on those ecosystems. Ongoing reflection was an integral aspect of this service-learning program and students reflected informally as well as through structured class discussion and by creating artwork. To conclude the project, the students then selected a method if educating the community regarding pollution. Suggested ideas included video taping skits to inform others about pollution, developing a school-wide recycling program, or making posters to raise pollution awareness. Ultimately, the students decided to perform a play for the preschool, elementary, and middle school as well as the parent community. They felt this would educate the largest number of people in a fun, entertaining way. The service-learning project for Cycle 2 addressed these essential questions: “What is a seed? How do seeds grow? Why do we need seeds? Why are seeds important to the CDS community?” The purpose of this project was for students to learn about process of seed growth while exploring their school community. This second cycle followed the same California state standards for science, math, and language arts in kindergarten that were addressed in Cycle 1 of the study. 13 The seeds unit was conducted over a five-week period in the fall semester of 2012. Over the course of the project, students responded to both fiction and non-fiction children’s literature about seeds, their growth, and communities. They participated in weekly planting at the school farm, planted in the classroom, and visited the local pumpkin patch. Ongoing reflection was an integral aspect of this service-learning program and students reflected through structured class discussion and by creating artwork. To conclude the project, the students used their knowledge of seeds and their school community to choose an area within the school to plant a kindergarten garden. Quantitative Data Quantitative data was collected through grading of student work using a rubric (see Appendix A). These artistic assignments where students answered different prompts such as “What can you do to help the environment?” or “What would you like to do with your vegetables when we harvest them?” were given at the beginning, middle, and the end of the service-learning project (see Appendix D and E). The assignments focused on student’s knowledge of the subject matter, and depth of reflection prior to the service-learning project, during, and after the culminating event. The researcher also assessed student’s engagement levels during both artistic and oral reflections for a focus group of 10 students using the “Engagement Checklist” (see Appendix B). This checklist focused on physical behaviors that students’ exhibited during both oral and artistic reflection times 14 such as “positive body language” and “consistent focus.” Lastly, I noted whether or not a student participated in both oral and artistic reflection activities. Qualitative Data Qualitative data was collected throughout the service-learning project and included observation notes and audio recordings of student’s statements. I took observation notes as students engage in the service-learning project and as they participate in reflection. These observation notes and audio recordings provided an objective account of the student’s reflections about the service-learning project. These notes also provided an account of the students’ experiences while participating in the project. Validity and Reliability The present study employed a number of strategies for maximizing validity and the overall trustworthiness of the study. The first legitimation type I used was the multiple validities legitimation. Onweugbuzie and Johnson (2006) state that, “this refers to the extent to which all relevant research strategies are utilized and the research can be considered high on the multiple relevant validities” (p. 59). Since my study is a mixed methods research project, I implemented several different research strategies such as observation, oral recordings, and analysis of student work. By using valid qualitative and valid quantitative techniques, I ensured valid conclusions. In addition to triangulating the methods, I triangulated the data. I analyzed evidence from several sources and individuals, which allowed me to compare the findings and build a theme. 15 The last legitimation type that I felt would be useful to my project is disconfirming evidence. Creswell and Clark (2011) stated that this is: Information that presents a perspective that is contrary to the one indicated by the established evidence. The report of disconfirming evidence in fact confirms the accuracy of the data analysis, because in real life, we expect the evidence for themes to diverge and include more than just positive information. (p. 212) Because my sample size is 29 students in Cycle 1 and 23 students in Cycle 2, I had a large amount of qualitative data to analyze. Both the quantitative and qualitative data I obtained allowed me to explore the importance of utilizing ongoing reflection while implementing a studentdriven service-learning unit. Although this research was only performed on two kindergarten classes, the data I collected led to valuable results that can be utilized by myself and other teachers in the future. 16 Chapter 3 Action Research Results This chapter examines the results of my quantitative and qualitative analysis of my action research. My study compared my students’ engagement during oral and artistic reflection activities while they engaged in a servicelearning project. This research was conducted in two cycles where the sample size was 27 students and 23 students respectively. Quantitative Results for Cycle 1 and Cycle 2 I used quantitative methods to answer the question: What impact does arts integration have on student engagement? I used a variety of methods to analyze my quantitative data. First of all, I looked at the overall scores from each students “Student Engagement Walkthrough Checklist,” (see Appendix B). This survey is broken down into 5 different sections: positive body language, consistent focus, verbal participation, student confidence, and fun and excitement. Students could score 1-5 points in each section for a maximum of 25 points. I used a paired t-test to analyze the overall scores, comparing the engagement scores of the oral reflection to the scores of the artistic reflection to determine if there is any significant statistical difference. Paired t-tests. Table 1 shows the comparison of engagement scores for oral and artistic reflections from cycle 1. The results of the t-test were t=6.4359. The two-tailed p value=.0001. By conventional criteria, this difference is considered to 17 be an extremely significant finding. These results showed that students were significantly more engaged during artistic reflections than during oral discussions. Table 1 Data Used for Paired T-­Test in Cycle 1 Cycle 1: Engagement Score Group Oral Discussion Artistic Reflection Mean 12.60 21.60 SD 6.10 2.59 SEM 1.93 0.82 N 10 10 Table 2 shows the comparison of engagement scores for oral and artistic reflections from cycle 2. Results of the t-test: t=15.4719. The two-tailed p value is less than .0001. By conventional criteria, this difference is considered to be an extremely significant finding. These results showed that students were significantly more engaged during artistic reflections than during oral discussions. Table 2 Data Used for Paired T-­Test in Cycle 2 Cycle 2: Engagement Score Group Oral Discussion Artistic Reflection Mean 10.10 23.90 SD 2.96 .99 18 SEM .94 .31 N 10 10 ANOVA. Next I used a repeated measures ANOVA test to compare each child’s grade on each artistic reflection. Artistic reflections were given at regular intervals at the beginning, middle, and end of the service-learning units. For the artistic reflections, students were given a prompt, which they used a combination of artwork, writing, and oral explanation to respond to. Some examples of prompts included: “What can you do to help the environment?” “What would you like to do with our vegetables when they are harvested?” I graded their artistic reflection using the Beginning Teacher Support and Assessment “Analyzing Student Work” assessment rubric (see Appendix A) where the possible scores were between 0-3. A student who scored 3 was exceeding the standards for the assignment, a score of 2 was meeting the standard, a score of 1 was approaching the standard, and a score of 0 was far below the standard. The ANOVA analysis allowed me to compare each assignment to the other to determine if there is a significant difference between the assignments. Table 3 shows the average and standard of deviation for the rubric scores of each of the three assignments given in cycle 1. In cycle 1, results of the repeated measures ANOVA: F(2, 80)=1.313, p=0.275 There is no statistical significant difference between these three measures. The students’ scores did not significantly change over time. 19 Table 3 Data Used for ANOVA in Cycle 1 Cycle 1: Artistic Reflection Rubric Scores Assignment 1 Assignment 2 Assignment 3 Avg 1.78 1.96 2.04 SD 0.64 0.71 0.44 Table 4 shows the average and standard of deviation for the rubric scores of each of the three assignments given in cycle 2. Results for the first two comparisons (between Assignment 1 compared to Assignment 2 and Assignment 2 compared to Assignment 3) yielded statistically significant results because p was less than .05. Comparison 3 (between Assignment 3 and Assignment 1) did not yield statistically significant results. This shows that there was significant change between some of the assignments. Table 4 Data Used for ANOVA in Cycle 2 Cycle 2: Artistic Reflection Rubric Scores Assignment 1 Assignment 2 Assignment 3 Avg 2.95 2.17 2.78 SD 0.20 0.49 0.52 20 Lastly, I used a Chi Squared test to compare the difference between the numbers of students who participated in the oral reflections compared to the number of students who participated in the artistic reflections. This data tells me whether a student did or did not participate in either the reflection discussion or the artistic reflection. I computed each set of reflections separately for 3 separate results. This allowed me to notice if any patterns became apparent. Table 5 Data Used for Chi Square Test in Cycle 1 Cycle 1: Engagement Rubric Scores Survey 1 Survey 2 Survey 3 Total # of students engaged during oral discussion 16 14 15 45 # of students engaged during artistic reflection 27 27 27 81 Total 43 41 42 126 Table 5 shows the number of students engaged during oral discussions vs. artistic reflections in cycle 1 of my research. For the Chi Square Test, my results were as follows: x2= 1.6642. The number of degrees of freedom was 2, so my x2 value was lower than any value noted on the chart, therefore the p value was not significant. This result may be due to the fact that my sample group was only 27 students. Although there were a greater number of students engaged during the artistic reflections than the oral discussions, as noted in the above table, the total amount surveyed may have not been large enough to created a statistically 21 significant result. Table 6 Data Used for Chi Square Test in Cycle 2 Cycle 2: Engagement Rubric Scores Survey 1 Survey 2 Survey 3 Total # of students engaged during oral discussion 8 3 9 20 # of students engaged during artistic reflection 23 23 23 69 Total 31 26 32 89 Table 6 shows the number of students engaged during oral discussions vs. artistic reflections in cycle 2 of my research. In cycle two, my results were x2= 8.401. The number of degrees of freedom was 2, so my x2 value was between .010 and .025. Therefore my results were statistically significant because they fell below the .05 confidence interval. Overall, my results show that a greater number of students showed engagement during artistic reflection activities. Many of my results were not statistically significant, however, due to my small sample size. Although some of the results are not statistically significant, each method of statistical analysis showed higher levels of engagement during the artistic reflection activities compared to oral discussions. Qualitative Results for Cycle 1 22 In Cycle 1 of my study, my students were engaged in a service-learning project exploring humans’ effect on the environment. They learned about different types of pollution, engaged in a classroom visit from the Sunnyvale Recycling Center and Sunnyvale Water Treatment Center, and visited a local watershed to look for evidence of pollution and its effects on animals in the area. I used qualitative methods to answer the question: What is the process of integrating art into a kindergarten service-learning project on the environment? I analyzed my data using three different methods. The techniques I decided to use to analyze my qualitative data were: constant comparison analysis (coding) for all data, latent content analysis for photos and student work, and manifest content analysis for observation notes. I decided to use constant comparison analysis (coding) to look at all my data because it is the most commonly used method of analyzing qualitative data and it allowed me to look for themes in my data. To analyze my photos and students artwork I used latent content analysis. I decided to use manifest content analysis for my observation notes because it allowed me to identify certain behaviors that students exhibited. As I listened to the audio recordings, looked through photos from the activities my students completed, and read over my observation notes, a few themes became apparent. I noticed an overall increase in student interest in this unit. I also noticed that students were using content area vocabulary correctly and with enthusiasm. Lastly, I noticed an increased feeling of unity and civic mindedness. 23 One place I noticed an increase in student interest in this unit was through the school-home connection. We began our service-learning unit on the environment with a letter home to Figure 1. Student building with recycled materials parents on Friday asking students to bring in recyclable materials. On Monday we got a few plastic water bottles and a couple cardboard boxes. Throughout the week, a few more items trickled in. As we got deeper and deeper into our unit, students started arriving at school with armfuls of recyclables. One parent arrived carrying a huge cardboard box filled with cans, bottles, and cereal boxes. “He won’t let me put anything in our trash can,” the parent said about his son. “He reminds me to recycle everything - all the time!” Our students knew that they could build and sculpt with the recyclable materials at school during their free-choice time (see Figure 1). They also looked forward to measuring and sorting the different recyclables during math. Over the course of this unit, I noticed an increase in my students’ use of content area vocabulary like environment, reduce, reuse, recycle, and pollution. One day I was on my usual recess duty and heard two students talking. One girl had a ladybug on her hand and she wanted to put it in a jar and keep it. The other student told her, “No! You have to put it back on the bush. It is part of the 24 environment.” Another day a student asked me if I had more paper for them to draw on. Before I could answer, another child told him, “Just turn your paper over. You can reuse it.” These examples show that my students are applying their content-area knowledge and vocabulary to their world. They are using the new vocabulary correctly in context, forming more developed and specific ideas. I also noticed an increased feeling of unity and civic-mindedness in my students during and after this unit. As students began to learn more about pollution and the environment, especially at a local level, I saw them taking action without prompting from me. I noticed several students picking up trash on the playground that did not belong to them. They also Figure 2. Students watering plants on the yard sorted this trash into the correct receptacle. In about the second week of our unit, three girls in my class noticed that some of the flower planters we had planted were dry (see Figure 2). They asked me for the watering can and took the initiative to water all the planters in the school. This has become a daily ritual for my students, even after the unit was long over. Everyday during recess, different students got the watering can by themselves, filled it up, and watered the plants. 25 During the second week of the unit, my students also realized that one thing they could do to help the environment was to teach other people. They asked me to hang up their first artistic reflections outside so that other students and parents could look at them and learn from them. Several students began to teach their parents and siblings different ideas we discussed in class. One parent came to me and said, “My son noticed there was a lot of smog Figure 3. Students painting recycled materials to build sets for their play coming out of my car. He told me I had to take the car to be fixed because smog pollutes the air.” This boy was using the new vocabulary he learned and the new concepts he learned to effect change on his environment. My students enjoyed the idea of educating others. They decided that they wanted to finish our unit with a play to show what they learned about the environment. The students chose songs to sing in the play that we had been learning throughout the unit. They also decided that they wanted to create the sets and props for the play (see Figure 3). The students created trees for the backdrop, painted a lake, and used recycled materials to make props like binoculars. Students who wanted speaking parts signed up for parts and other students who felt more nervous about performing had group parts. 26 We decided that we would invite the preschool to our play so that we could teach them what we learned. Different students came to me asking if we could please invite their parents so they could learn too. Other students wanted to invite their siblings in the school so they could teach them. We ended up inviting the whole school and all the kindergarten parents to our play, which you can view here: http://vimeo.com/37070169 Password: cafard Qualitative Results for Cycle 2 Cycle 2 of my research was conducted while students were completing a service-learning project around the theme of seeds and the local community. During this unit my students collected different seeds from the school and the neighborhood, investigated these seeds, planted them, they visited the local pumpkin patch and explored the life cycle of a pumpkin. They also explored the idea of a community garden as part of their culminating unit. I used qualitative methods to answer the question: What is the process of integrating art into a kindergarten service-learning project on the environment? Again, I analyzed my data using three different methods: Constant Comparison Analysis (coding) for all data, latent content analysis for photos and student work, and manifest content analysis for observation notes. 27 As I began this service-learning unit with my new class of kindergarteners, I noticed two new themes emerging. I learned very quickly that engagement during oral reflections was low. Listening to the audio recordings, looking through photos from the activities my students completed, and reading over my observation notes only made this observation more clear. Throughout my qualitative analysis, I also realized that my students were developing a sense of interconnectedness with their world. They were asking questions about where their food comes from, they were collecting seeds, leaves, and flowers on their walk to school, and then comparing them to the diagrams in some of the books we read. I knew when I was designing this unit that beginning the year with a service-learning project would be difficult for incoming kindergarteners. Kindergarten is a huge adjustment for most children as preschool is more play oriented, while kindergarten is more structured and academic. At the beginning of the year, students are learning how to move from their seats on the carpet to their table spots, how to line up, how to use a glue stick properly and so on. Essentially, they are learning how to be in school. I knew that a service-learning unit stretches the critical thinking skills of students and that this might be difficult for such a young group. In addition to my students’ relative inexperience with school and a structured learning environment, this class included a wide range of academic ability and social-emotional maturity. This combination resulted in a class that 28 had great difficulty contributing to grand conversations and needed other outlets to ask questions, process information, and reflect upon their learning. During our first oral reflection in our seeds unit, I noted that only 8 out of 23 students participated. Although these 8 students were very engaged in our conversation, a much Figure 4. Students engaged in small group discussions at their tables larger portion of the class was not. Students were physically showing me the signs of disengagement: looking other directions, laying down on the rug, and talking with their neighbors. Allowing students to reflect artistically, gave me the chance to better assess each students’ learning because everyone was engaged in the activity. While students completed their artwork depicting a question they had about seeds, I floated through the room listening to their conversations. Each table group was discussing their knowledge about seeds (see Figure 4). I heard things like, “Every plant has seeds,” “Seeds come from inside the plant,” and “Why do plants need seeds?” These discussions were happening naturally, without my prompting. My students were much more engaged in small group conversations while completing their work than in a whole class discussion. 29 As the unit continued, I began to notice my students developing a sense of interconnectedness to their world. One student arrived at school with a ziplock baggie full of different seeds. “I found these in the food I was eating last night!” she told me. She had a collection of small tomato seeds, a large avocado seed, and some tiny strawberry seeds. Another student arrived to school with some flowers she had picked on her walk to school. She asked, “Do you think we can look for seeds in these flowers?” When one student was eating soy beans for his snack, he peeled the outside covering off the soybean and said, “Hey! It’s the seed coat!” I asked him if he could find anything else we have been learning about. He split the soybean in half and quickly found the baby plant inside it. When designing this unit, it was important to me that the students developed an understanding of where their food comes from; that it isn’t made inside Trader Joe’s but that fruits and vegetables grow in farms around the state, country, and Figure 5. Student counting seeds inside a kiwi world. As the students learned more about seeds, I brought in the service-learning component of the unit. As we explored, they were also learning about their school community in social studies. We combined these two units as the students investigated the gardens and farms in their community and chose a place to plant a vegetable garden that they would harvest in January (see Figure 6). There is a 30 retirement home adjacent to the school that has a community garden for the retirees. We discussed the idea of a community garden and the students agreed that they would like to plant there. In January we will harvest a crop of carrots, radishes, and lettuce, Figure 6. Students planting vegetables in the community garden and the students will decide what they want to do with their harvest. Each cycle of my research revealed the importance of using multiple methods of reflection during a service-learning environment. Each servicelearning project resulted in higher levels of student engagement and a stronger school-home or school-world connection. In the next section, I will compare the results of the two cycles and make recommendations for classroom application. 31 Chapter 4 Discussion Analyzing the results of my two cycles of research on the importance of using art as a method of critical reflection while students participated in servicelearning projects was very interesting. In this chapter, I will compare the results of both cycles, discuss the implications of these results for myself and other teachers, and discuss areas where my research could be expanded. Comparison of Results My quantitative data in both cycles of research showed there was a significant difference between the level of student engagement during artistic activities rather than oral discussions. In cycle one, there was no statistically relevant improvement in their artistic reflections and no statistical significance between the number of students engaged during artistic reflections as compared to the number of students engaged during oral discussions. In cycle two however, there was statistical relevance in both the level of improvement in their artistic reflections and the number of students engaged during artistic reflections compared to oral discussions. In both cycles of my research, data showed that most students were more engaged during artistic reflections rather than oral reflections. Each cycle of research was conducted on one class of students, 27 students and 23 students respectively. I feel that if this study was implemented in a larger scale, there may have been more statistically significant findings. Cycle two of my research showed that there were more students engaged during the 32 artistic reflection than during the oral discussion. This finding shows the importance of using multiple types of reflection when asking students to share their thoughts and observations. It is important that teachers implement both oral and artistic types of reflections in their classrooms. Limiting reflection activities to one method limits the amount of students participating and limits student engagement. Reflection activities stimulate critical thinking, promote questioning, and connect students to the lesson. If only one method of reflection is utilized, other types of learners are less able to benefit from the activity. In my research study, although not all my students participated in the oral reflections, the oral activity provided my class with a springboard when entering into their artistic work. Although not all students showed high levels of engagement during the oral reflection, some students participated eagerly and benefited from the opportunity to ask questions and share their ideas. The oral reflection activity may have benefited other students, even though they were not displaying visible signs of engagement, because they heard the ideas contributed by their peers. Even though these students did not share their own ideas, they had the opportunity to contemplate their classmates’ ideas and build on to them. As students began their artistic reflections, the ideas and vocabulary from their whole group discussion became a part of their small group conversations even for students who were not active participants in the whole class discussion. 33 My qualitative data shows the process of integrating art into a kindergarten service-learning project on the environment requires flexibility from the classroom teacher. As both units progressed, I observed my students’ reactions to the activities and I followed their lead, trying to integrate art whenever possible. I found that analyzing my students oral and artistic reflections closely allowed me to understand their interests more clearly. In our unit about the environment, we sang about the environment, we danced like trees blowing in the wind, we watched videos, we read stories, we drew pictures, and we made sculptures. In our unit about seeds, we drew our observations of our bean plants as they grew, we collaged with different types of seeds, we made patterns and sorted seeds, we sang songs about seeds, and we painted seeds. Many of the activities in both these units did not exist in my original curriculum, but were implemented because they were ideas that came from the students. Not only were my student highly engaged in these activities because they had thought of them, these activities met the needs of different types of learners in my classroom because they were so varied. As the students delved deeper into their creativity and into the content of these units, I observed my students move through Bloom’s taxonomy (see Figure 7), with art as the springboard. My students began by recalling Figure 7. Blooms Taxonomy 34 information they learned from books or life experiences and then began to apply that knowledge by dramatizing, illustrating, interpreting, and investigation those ideas. For example, during the unit on the environment in Cycle 1 of my research, we began by reading stories about the environment and then drawing pictures of parts of the story they recalled. This activity would be categorized in the “Remembering” portion of Bloom’s taxonomy, which is at the base of the pyramid. By the end of the unit, they were building recycling machines and factories out of recycles materials and designing their own play to educate the rest of the school community. These types of activities, where the student is “creating a new product or point of view” (Overbaugh, 2011) are “Creating” activities, which form the tip of the pyramid of Bloom’s taxonomy. They began to build connections between their learning at school and their greater world. They brought pieces of their lives into the classroom and knowledge from their classroom into parts of their life. They compared and questioned, evaluated and argued with each other, and finally, they took action to affect change. My primary research question asked: How is depth of reflection through art related to student levels of engagement? The quantitative and qualitative data in both cycles of my research showed that students were very engaged while completing their artistic reflections. My quantitative rubric scores also showed that I had more than two-thirds of my class in my first cycle of research meeting or exceeding my expectations for each artistic reflection and more than three-quarters of my class in my second cycle of research. My data shows that art can be a 35 catalyst for student engagement and that when students are actively engaged they will perform at higher levels. These findings align with the research I referenced in my literature review, where pre-school aged children showed improvement in their Early Learning Standards when an arts-based curriculum was implemented (Phillips, Gorton & Sachdev, 2010, p. 111). Implications for Teaching Implementing two cycles of a service-learning unit with kindergarteners has both inspired me and exhausted me. There were several parts of these units that felt very daunting to me as a teacher. First, beginning a unit that was not entirely planned made me feel out of control. Second, as my literature-review showed, not many teachers have attempted service-learning projects with kindergarten age students. However, my research shows that these units resulted in increased student engagement, a curriculum design that reached more types of learners, and higher levels of intellectual behavior. Setting out to implement a unit driven by student reflection can be a scary task. As I set aside time for the unit in my plan book, I left many blocks of time open with just the label “Environment?” next to it. That question mark was a bold step for me. It showed that I didn’t know what activity we would do during that time. It meant that I was going to leave that choice open to the students, to allow them to decide during their reflection activities. My recommendations to teachers as they attempt a student-driven unit, is to set aside a specific amount of time for the whole unit; in my class I allotted three weeks for cycle one and five weeks for 36 cycle two. Having a concrete timeline provides some control. My other recommendation is to integrate as many core-components into the activities that the students want to do. For example, during my unit on seeds, the students decided they wanted to bring in fruits from home and make fruit salad. As students chopped their fruit for the salad, they observed, counted, and drew the seeds inside their fruit, which addressed (or met) both math and science standards. They also wrote about their experiences as part of writer’s workshop. Because making a fruit salad was their idea, I found students to be much more engaged in the activities. I also found that students were very engaged in the activities because of the service-learning aspect of the units. When conducting my literature review, I did not find any service-learning projects where kindergarteners were doing the service; kindergartners were only the recipients of the service in the projects. When sharing my ideas for my project with my cohort in the California State University, Fresno Masters of Arts in Teaching program, my cohort responded with reservations saying, “I don’t know if you should try that with kindergarteners.” When actually implementing the units, I found my students to be inspired by the responsibility of taking action in their community. They responded energetically to the idea of teaching others what they have learned. This concept integrated into all aspects of their learning, and it moved them to higher levels of intellectual behavior as exhibited in Bloom’s taxonomy. As a 37 teacher, I found these units to move more smoothly and be more energizing because my students were so motivated and engaged to help their community. Although I first felt anxious at the idea of a student-driven service-learning project, I feel these two units have resulted in some of the best lessons I have ever taught. At the end of the 2011-2012 school year, my kindergarteners reflected back on their favorite activities. Overwhelmingly, their favorite lessons came out of our unit on the environment. I have received a great amount of positive feedback not just from my students, but from parents and administrators as well. Moving forward, I intend to integrate at least one service-learning unit into my curriculum each year. I also plan to redesign other units during the year to be more student-centered. I recommend that early elementary teachers attempt student-driven service-learning units in their class. Although the process can sometimes feel overwhelming and a little out of control, I have found that the results are well worth the extra effort. Conclusion Overall, focusing on arts integration through service–learning projects was very beneficial to my class in both cycles of my research. In my second cycle of research, my students received an even greater benefit from arts integration than the first, because participation during the oral reflection activities was so low. Artistic reflections allowed all of my students to participate in brainstorming and building ideas to drive and direct our unit. By integrating art as a critical method of reflection, I am confident that I was making sure that every student was 38 engaged and able to express his or her knowledge or questions about the lesson. My observations and quantitative data confirmed this idea. My research would have benefited from a larger sample size and longer length of implementation. I hope that future researchers focus on kindergarteners as the executors of service-learning projects. Kindergarteners are ready for the responsibility of service-learning and react enthusiastically to the idea of helping their community. I also believe that more research on arts integration for early elementary students is needed. With growing budget cuts to art programs, arts integration is an important and viable approach to teaching core content, especially to younger students. I hope that teachers will be inspired by my research and use art as a method for critical reflection with their kindergarten and early elementary students. Even more so, I hope that teachers will take the risk and implement a student-driven, service-learning unit with their class. 39 References Behymer, A. (2003). Kindergarten writing workshop. The Reading Teacher, 57, 85-88. Bloom's Taxonomy. (n.d.). Old Dominion University. Retrieved December 4, 2011, from http://www.odu.edu/educ/roverbau/Bloom/blooms_taxonomy.htm Cohen, D., & Crabtree, B. (2006). Qualitative research guidelines project. Retrieved from http://www.qualres.org/HomeConf-3807.html Creswell, J.W. & Clark, P. V.L. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Horn, M., & Giacobbe, M. E. (2007). Talking, drawing, writing, lessons for our youngest writers. Portland, Maine: Stenhouse Pub. Hutzel, K., Russel, R., & Gross, J. (2010) Eighth graders as role models: A service learning art collaboration for social and emotional learning. Early Childhood Education Journal, 37, 447-460. Jones, R. D. (2009). Data Driven Engagement. Student engagement teacher handbook. New York: International Center for Leadership in Education, 31. Kramer, Thomas J., Caldarella, P., Christensen, L., and Shatzer, R. H. (2009) Social and emotional learning in the kindergarten classroom: Evaluation of the Strong Start curriculum. Early Childhood Education Journal, 37(303), 303-09. 40 National Service Learning Clearinghouse. (2012). National service-learning clearinghouse. Retrieved from http://www.servicelearning.org/whatservice-learning Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Collins, K. M. (2001). A typology of mixed methods sampling designs in social science research. The Qualitative Report, 12(2), 281-316. Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Johnson, R. B. (2006). The validity issue in mixed research. Research in the Schools, 13(1), 48-63. Phillips, R., Gorton, R., Pinciotti, P., & Sachdev, A. (2010). Promising findings on preschoolers’ emergent literacy and school readiness in arts-integrated early childhood settings. Early Childhood Education Journal, 38(2), 111122. doi:10.1007/s10643-010-0397-x Soundy, C. S., & Drucker, M.F. (2010) Picture partners: A co-creative journey into visual literacy. Early Childhood Education Journal, 37(6), 447-60. Walter, O. (2010) The effects of the ‘Role Reversal Approach’ on teacher training models. Support for Learning, 25(3), 122-30. 41 Appendix A: Rubric Used for Analyzing Artistic Reflections 42 Appendix B: Sample of Engagement Checklist (Jones, 2009, p.31) 43 Appendix C: California Standards Addressed by Units Science 1a Students will make observations about water pollutants, measure pollutants, and predict outcomes. They will describe the physical properties of the water pollutants and the sites they visit. Science 3 a,c Students will identify characteristics of rivers, oceans and bays. They will identify resources from the earth and plan for the conservation and protection of these resources. Science 4 a,b Students will ask meaningful questions about the sources of pollution. They will describe the pollution that they see and record their observations. Social Studies 4 Students will compare and contrast features of their community and the environment Social Studies 3 Students will learn about different jobs in the community through a visit from the Clean Water Center Math Measurement Students will be able to measure what type of pollutant and Data 2 appeared most frequently. Math Counting and Students will count the number of pollutants found. Cardinality 1 Language Arts Writing 2,3 Students will use a combination of drawing, dictating, and writing to compose informative/explanatory texts about their research. They will retell events and react to their investigations. Language Arts Writing 8 Students will recall information from experiences or gather information on water pollution from provided sources to answer questions. Language Arts Comp& Students will participate in collaborative discussions Collaboration about water pollution and ask questions from specialists 1,3 or teachers to obtain more information. 44 Appendix D: Student Work Sample Artistic reflection to answer prompt: “What can you do to help the environment?” 45 Appendix E: Student Work Sample Artistic reflection to answer prompt: “What do you want to do with our vegetables when they grow?”