Document 13158424

advertisement

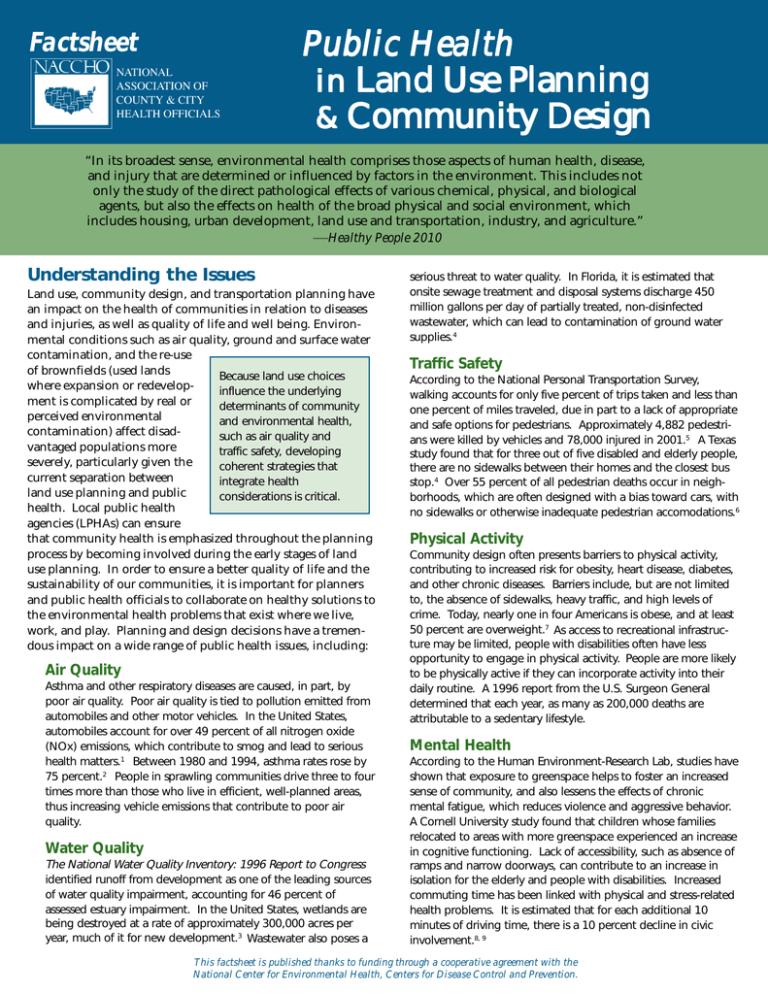

Public Health in Land Use Planning & Community Design Factsheet “In its broadest sense, environmental health comprises those aspects of human health, disease, and injury that are determined or influenced by factors in the environment. This includes not only the study of the direct pathological effects of various chemical, physical, and biological agents, but also the effects on health of the broad physical and social environment, which includes housing, urban development, land use and transportation, industry, and agriculture.” —Healthy People 2010 Understanding the Issues Land use, community design, and transportation planning have an impact on the health of communities in relation to diseases and injuries, as well as quality of life and well being. Environmental conditions such as air quality, ground and surface water contamination, and the re-use of brownfields (used lands Because land use choices where expansion or redevelopinfluence the underlying ment is complicated by real or determinants of community perceived environmental and environmental health, contamination) affect disadsuch as air quality and vantaged populations more traffic safety, developing severely, particularly given the coherent strategies that current separation between integrate health land use planning and public considerations is critical. health. Local public health agencies (LPHAs) can ensure that community health is emphasized throughout the planning process by becoming involved during the early stages of land use planning. In order to ensure a better quality of life and the sustainability of our communities, it is important for planners and public health officials to collaborate on healthy solutions to the environmental health problems that exist where we live, work, and play. Planning and design decisions have a tremendous impact on a wide range of public health issues, including: Air Quality Asthma and other respiratory diseases are caused, in part, by poor air quality. Poor air quality is tied to pollution emitted from automobiles and other motor vehicles. In the United States, automobiles account for over 49 percent of all nitrogen oxide (NOx) emissions, which contribute to smog and lead to serious health matters.1 Between 1980 and 1994, asthma rates rose by 75 percent.2 People in sprawling communities drive three to four times more than those who live in efficient, well-planned areas, thus increasing vehicle emissions that contribute to poor air quality. Water Quality The National Water Quality Inventory: 1996 Report to Congress identified runoff from development as one of the leading sources of water quality impairment, accounting for 46 percent of assessed estuary impairment. In the United States, wetlands are being destroyed at a rate of approximately 300,000 acres per year, much of it for new development.3 Wastewater also poses a serious threat to water quality. In Florida, it is estimated that onsite sewage treatment and disposal systems discharge 450 million gallons per day of partially treated, non-disinfected wastewater, which can lead to contamination of ground water supplies.4 Traffic Safety According to the National Personal Transportation Survey, walking accounts for only five percent of trips taken and less than one percent of miles traveled, due in part to a lack of appropriate and safe options for pedestrians. Approximately 4,882 pedestrians were killed by vehicles and 78,000 injured in 2001.5 A Texas study found that for three out of five disabled and elderly people, there are no sidewalks between their homes and the closest bus stop.4 Over 55 percent of all pedestrian deaths occur in neighborhoods, which are often designed with a bias toward cars, with no sidewalks or otherwise inadequate pedestrian accomodations.6 Physical Activity Community design often presents barriers to physical activity, contributing to increased risk for obesity, heart disease, diabetes, and other chronic diseases. Barriers include, but are not limited to, the absence of sidewalks, heavy traffic, and high levels of crime. Today, nearly one in four Americans is obese, and at least 50 percent are overweight.7 As access to recreational infrastructure may be limited, people with disabilities often have less opportunity to engage in physical activity. People are more likely to be physically active if they can incorporate activity into their daily routine. A 1996 report from the U.S. Surgeon General determined that each year, as many as 200,000 deaths are attributable to a sedentary lifestyle. Mental Health According to the Human Environment-Research Lab, studies have shown that exposure to greenspace helps to foster an increased sense of community, and also lessens the effects of chronic mental fatigue, which reduces violence and aggressive behavior. A Cornell University study found that children whose families relocated to areas with more greenspace experienced an increase in cognitive functioning. Lack of accessibility, such as absence of ramps and narrow doorways, can contribute to an increase in isolation for the elderly and people with disabilities. Increased commuting time has been linked with physical and stress-related health problems. It is estimated that for each additional 10 minutes of driving time, there is a 10 percent decline in civic involvement.8, 9 This factsheet is published thanks to funding through a cooperative agreement with the National Center for Environmental Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Factsheet Public Health in Land Use Planning & Community Design “As a former local health official, I believe that [we] need a seat at the [land use] planning table to ensure a better quality of life by promoting decisions that increase physical activity, address injury prevention, and improve air and water quality. NACCHO encourages collaborative efforts between health officials, planners, and other disciplines to integrate the public health perspective into the land use planning process.” —Pat Libbey, Executive Director, NACCHO Hazardous Materials Expanding the role of LPHAs in commenting on development plans. Electing health officials to planning boards and other community positions. Attending planning meetings regularly. Serving as information conduits, keeping abreast of current processes and policies, and disseminating information to community members. Adopting local resolutions on health and land use/ transportation planning. Zoning regulations first emerged from environmental health concerns that sought to protect people from harmful practices (i.e., separation of housing from industry). Despite decades of separation, the link between land use planning and public health is being reestablished. Hazardous materials are transported, stored, manufactured, or disposed of in many communities. Often, zoning and environmental regulations do not provide for the separation of incompatible land uses, like placing housing near areas zoned for use or storage of hazardous materials. In addition, hazardous waste sites continue to be a significant concern. The Environmental Protection Agency determined that one in every four children in the United States lives within one mile of a National Priorities List hazardous waste site. The United Nations Environment Programme links exposure to heavy metals with certain cancers, kidney damage, and developmental retardation. Social Justice Evidence demonstrates that environmental hazards, air pollution, heat-related morbidity and mortality, traffic fatalities, and substandard housing disproportionately affect low-income and minority populations. Environmental Protection Agency data shows that Hispanics are more likely than Whites to live in air pollution non-attainment areas. Asthma mortality is approximately three times higher among Blacks than it is among Whites. As neighborhoods undergo gentrification, people of a lower socioeconomic status are pushed to the fringes, limiting their access to social services. A lack of public transportation options often exacerbates the problem and leaves minority populations disproportionately affected by less access to quality housing, healthy air, good quality water, and adequate transportation. Role of LPHAs Because most land use planning occurs at the local level, it is essential that LPHAs become more integrated in the planning process in order to address and prevent unfavorable outcomes for public health. LPHAs must assume a diverse and proactive approach in order to be successful in this role, including: Forging partnerships between LPHAs and local planning and transportation officials in order to bring health to the planning table. Using data to arm and inform stakeholders and decisionmakers, substituting national data if local data is unavailable. NACCHO’s Role NACCHO’s goal is to integrate public “Public health health practice more effectively into professionals need to the land use planning process by view the built enhancing the capacity of LPHAs to environment as having be involved in land use decisionas much influence on making. Through development of public health as tools and resources, NACCHO also vaccines.” (Jackson, strives to promote the involvement of Kochtitzky, 2001) LPHAs with elected officials, planners, and community representatives in regard to health issues in land use planning. Focus groups conducted by NACCHO during the past year explored strategies for integrating public health and land use planning. To learn more, visit www.naccho.org/project84.cfm, or call (202) 783-5550 and ask to speak with a member of NACCHO’s environmental health staff. 1 Environmental Protection Agency. www.epa.gov/air/urbanair/nox/what.html. National Center for Environmental Health. www.cdc.gov/nceh/airpollution/ asthma/children.htm. 3 National Audubon Society. Population and Habitat Program: Audubon Backgrounder. Available at www.audubonpopulation.org/sections/pubsvids/ popwetlands.cfm (2003, May 30). 4 Jackson, Richard and Chris Kochtitzky. “Creating a Healthy Environment: The Impact of the Built Environment on Public Health.” Washington, DC: Sprawl Watch Clearinghouse, 2001. www.sprawlwatch.org. 5 National Highway Transportation Safety Administration. Traffic Safety Facts 2001. Available at www-nrd.nhtsa.dot.gov/pdf/nrd-30/NCSA/TSF2001/ 2001pedestrian.pdf (2003, May 15). 6 Surface Transportation Policy Project and Environmental Working Group. “Mean Streets, Pedestrian Safety and Reform of the Nation’s Transportation Law.” The Environmental Working Group/The Tides Center, 1997. 7 National Institutes of Health. www.niddk.nih.gov/health/nutrit/pubs/ statobes.htm. 8 Frumkin, Howard. “Urban Sprawl and Public Health.” Public Health Reports, Volume 117. September 2001. 8 Putnam, Robert D. “Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community.” New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000. 2 NACCHO is the national organization representing local public health agencies. NACCHO works to support efforts that protect and improve the health of all people and all communities by promoting national policy, developing resources and programs, seeking health equity, and supporting effective local public health practice and systems.