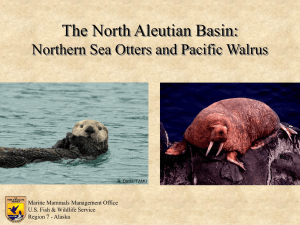

Pacific Walrus Management in a World of Changing Climate:

advertisement