Modern Applications of the Rule Against Perpetuities to Oil and Gas

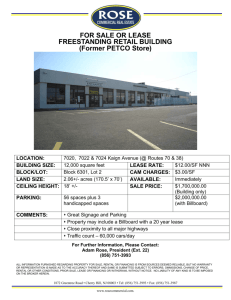

advertisement