T E G

advertisement

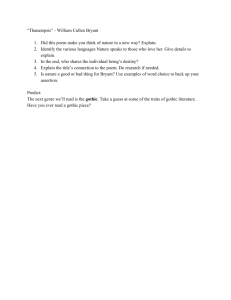

THE EVOLUTION OF THE GOTHIC Luigi Capuana, Ugo Tarchetti, M.R. James and Gerald Durrell LECTURE OVERVIEW AND STORIES The changing function of the Gothic Ugo Tarchetti, ‘Le leggende del castello nero’ (1869) Later Gothic and the Uncanny Luigi Capuana, ‘Un Vampiro’ (1906) M.R. James, ‘A School Story’ (1911) Gerald Durrell, ‘The Entrance’ (1979) Fear in later Gothic narratives Copyright: R. Sibley, University of Warwick 2014 THE EVOLUTION OF THE GOTHIC Every literary movement and genre evolves over time. What happens when the Gothic is detached from Romanticism and the Sublime? Do later Gothic texts have the same function as earlier ones? How do these later texts compare to the earlier narratives in terms of content and narration? Copyright: R. Sibley, University of Warwick 2014 James Gillray, Tales of Wonder 1802 Copyright R. SIbley, University of Warwick 2013 THE GOTHIC AND THE SUBLIME Casper David Friedrich, Cloister Cemetery in the Snow (1817-19) Horace Vernet, Stormy Coast Scene After a Shipwreck (1830s) What happens when the Gothic becomes detached from the Sublime? 1818 1847 Jane Austen, Northanger Abbey Emily Bronte, Wuthering Heights 1922 1931 1955 1979 1999 2008 Todd Browning, Dracula / James Whale, Franeknstein Charles Laughton, Night of the Hunter Gerald Durrell, ‘The Entrance’ Alan Moore, From Hell True Blood 1907 1897 F. W. Murnau, Nosferatu M.R. James, Ghost Stories of an Antiquary Bram Stoker, Dracula 1886 1869 1808 Mary Shelley, Frankenstein Ugo Tarchetti, ‘Le leggende del castello nero’ Robert Louis Stevenson, Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde 1796 1764 Matthew Lewis, The Monk Hroace Walpole, The Castle of Otranto LATER GOTHIC TIMELINE FROM THE SUBLIME TO THE SUPERNATURAL Movement from the Sublime of Romanticism towards a new form of Gothic after the mid C19th. Texts like Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Doctor Jekyll and Mister Hyde pick up on elements of Shelley’s Frankenstein but are moving closer to science fiction. Later C19th Gothic narratives are less revolutionary – are part of an established tradition within C19th literature. Capuana interesting example of ‘scientific’ response to supernatural events – blends verismo with the Gothic to create a ghost story. Copyright: R. Sibley, University of Warwick 2014 THE GOTHIC IN FILM Copyright: R. Sibley, University of Warwick 2014 TWENTIETH-CENTURY GOTHIC M.R. James a key figure in C20th Gothic – saw himself as a Victorian so his stories often look back to that age. His stories are very contained and are not commenting on the wider world – just there to scare the reader. Move towards psychological horror – terrible events are suggested rather than explicitly outlined. Same with Durrell’s story – is a very effective piece of entertainment but not trying to critique contemporary society. Copyright: R. Sibley, University of Warwick 2014 THE GHOST STORY VS THE GOTHIC The Gothic is now synonymous with the ghost story – such as the work of M.R. James. The ghost story is far simpler than the earlier Gothic narratives – intended to scare rather than anything else. Also, the ghost story rarely challenges accepted authorities or social orders. It is also a ‘safe’ form of entertainment – the audience enjoys being scared in a predictable or formulaic way, whereas earlier Gothic narratives were innovative and wholly unpredictable for their readership. Copyright: R. Sibley, University of Warwick 2014 M.R. JAMES AND THE GHOST STORY An institutional location (abbey, school, cathedral) Male protagonist with scholarly pretensions Discovery of an antiquarian object that invokes supernatural events Why is this formula significant? Copyright: R. Sibley, University of Warwick 2014 M.R. James’s ghost stories involve: FREUD, ‘THE UNCANNY’ (1919) As I was walking, one hot summer afternoon, through the deserted streets of a provincial town in Italy which was unknown to me, [...] I hastened to leave the narrow street at the next turning. But after having wandered about for a time where my presence was now beginning to excite attention. I hurried away once more, only to arrive by another détour at the same place yet a third time. Now, however, a feeling overcame me which I can only describe as uncanny, and I was glad enough to find myself back at the piazza I had left a short while before, without any further voyages of discovery. Other situations which have in common with my adventure an unintended recurrence of the same situation, but which differ radically from it in other respects, also result in the same feeling of helplessness and of uncanniness. So, for instance, when, caught in a mist perhaps, one has lost one's way in a mountain forest, every attempt to find the marked or familiar path may bring one back again and again to one and the same spot, which one can identify by some particular landmark. Or one may wander about in a dark, strange room, looking for the door or the electric switch, and collide time after time with the same piece of furniture. Copyright: R. Sibley, University of Warwick 2014 without enquiring my way, I suddenly found myself back in the same street, THE ROLE OF THE OBJECT - TARCHETTI (‘Le leggende del castello nero’) Copyright: R. Sibley, University of Warwick 2014 “Era, meglio che in involto, un grosso plico quadrato in vecchia carta grigiastra macchiata di ruggine, e cucita lungo gli orli con filo bianco e a punti esatti e regolari che accusavano l’ufficio di una mano di donna. La carta, tagliata qua e là dal filo, e arrossata e consumata sugli orli, indicava che quel piego era stato fatto da lungo tempo. Mio zio lo ricevette dalle mani di mio padre, e lo vidi tremare ed impallidire nell’osservarlo. Tagliatane la carta, ne trasse due vecchi volumi impolverati, e non v’ebbe gettato su gli occhi, che il suo volto si coperse di un pallore cadaverico...” THE ROLE OF THE OBJECT - JAMES (‘A School Story’, p.112) Copyright: R. Sibley, University of Warwick 2014 “[Sampson] had a charm on his watch-chain [...] a gold Byzantine coin; there was an effigy of some absurd emperor on one side; the other side had been worn practically smooth, and he had had cut on it – rather barbarously – his own initials, G.W.S., and a date, 24 July, 1865. Yes, I can see it now: he told me he had picked it up in Constantinople: it was about the size of a florin, perhaps rather smaller. CONTEMPORARY GOTHIC The Gothic is now associated with High Victorian culture – the recent BBC adaptations of Dickens’ Great Expectations for instance. Also have the idea of Southern Gothic in the US – True Blood a good example, particularly the opening credit montage. For contemporary readers and viewers, the Gothic is now often distanced from its original impulses and elements, and is a convention rather than a challenge to accepted culture. Now more focused on corporeal fear rather than spiritual damnation. Copyright: R. Sibley, University of Warwick 2014 THE RISE OF THE DEAD – MARY SHELLEY (Frankenstein, 1818, p.59) Copyright: R. Sibley, University of Warwick 2014 “I slept, indeed, but I was disturbed by the wildest dreams. I thought I saw Elizabeth, in the bloom of health, walking in the streets of Ingolstadt. Delighted and surprised, I embraced her, but as I imprinted the first kiss on her lips, they became livid with the hue of death; her features appeared to change, and I thought that I held the corpse of my dead mother in my arms; a shroud enveloped her form, and I saw the grave-worms crawling in the folds of flannel.” THE RISE OF THE DEAD – TARCHETTI (‘Le leggende del castello nero’ 1869) Copyright: R. Sibley, University of Warwick 2014 “Le sue forme piene e delicate che sentiva fremere sotto la mia mano, si appianarono, rientrarono in sé, sparirono; e sotto le mie dita incespicate tra le pieghe che s’erano formate a un tratto nel suo abito, sentii sporgere qua e là l’ossatura di uno scheletro... Alzai gli occhi rabbrividendo e vidi il suo volto impallidire, affilarsi, scarnarsi, curvarsi sopra mia bocca; e colla bocca priva di labbra imprimervi un bacio disperato, secco, lungo, terribile...” THE RISE OF THE DEAD - DURRELL Copyright: R. Sibley, University of Warwick 2014 “Most of the features below the eyes appeared to have been eaten away, either by decay or some disease akin to leprosy. Where the nose should have been there were just two black holes with tattered rims. The whole of one cheek was missing and so the upper and lower jaws, with mildewed gums and decaying teeth, were displayed. Trickles of saliva flooded out from the mouth and dripped down into the folds of the shroud. What was left of the lips were serrated with fine wrinkles, so that they looked as though they had been stitched together and the cotton pulled tight.” (‘The Entrance’, 1979, p.208) CONCLUSIONS The Gothic has evolved into a literary tradition with established formulae rather than remaining as a ‘counter-culture’ form. In contemporary cultural production, the Gothic is associated with a High Victorian setting rather than anything earlier or medieval. More recent Gothic narratives play on psychological horror rather than melodrama. The Gothic is now synonymous with the ghost story rather than more ambiguous narratives. Copyright: R. Sibley, University of Warwick 2014 QUESTIONS FOR THE SEMINAR How are these stories developing the Gothic genre – what are the key differences and similarities with Poe and Hawthorne? Who is creating meaning in these stories – the reader or the narrator? How do the concepts of good and evil function in these stories? Copyright: R. Sibley, University of Warwick 2014 QUESTIONS FOR NEXT WEEK What is the role of class and social hierarchy in verismo and naturalism? How does DeLedda’s view of rural Italy differ from Verga’s? What are the similarities and differences in narrative structure between Verga, Mann and DeLedda? How does each author use language to control the reader’s reaction to their work? Copyright: R. Sibley, University of Warwick 2014