R M D S

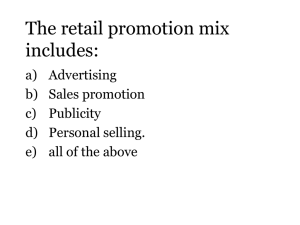

advertisement