CONFIDENTIALITY OF TEXAS MEDIATIONS: RUMINATIONS ON SOME THORNY PROBLEMS 77

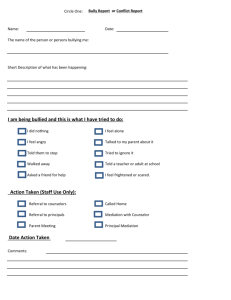

advertisement