612 Submitted to Professor Bruce Kra ... Independent Research Damon Richards

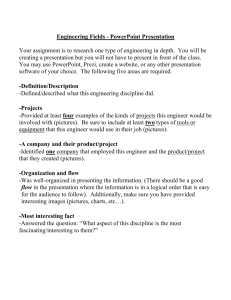

advertisement

SURVEY OF NEW t1EXICO HATER LAH

Submitted to Professor Bruce Kra mer

Independent Research

by

Damon Richards

612

I. INTRODUCTION

1.

Importance Of Hater

Water is one of our most important natural resources.

People have

recently become more cognizant of our need to discontinue rapid depletion

of dwindling supp 1i es of nonrepli ni shab 1e or s 1owly rep 1i ni shi ng natura 1

resources.

Our a\'Jareness, ho\':ever, anpears to only encompass hydrocarbons.

Humanity can survive, as it has in the past, without petroleum resources,

but we cannot and have never survived without water.

it is evident that a re-evaluation of our priorities

From this perspective

natural

regardin~

;

resource conservation and allocation is necessary.

l~ater

is an inte0ral part of everyday lives.

It is most often

thought of being important for oral consumption, but it also has many

other valuable purposes.

It is applied to crops, without which

have no fruit_or vegetables.

\'!e

vJOuld

It is needed for consumption by farm

animals and wildlife without which we would have no meat.

Water is also

used for domestic purposes such as washinq clothes and dishes.

It is also

used in manufacturing, industry, and recreation such as swimming, fishing,

and boating.

It is used to generate electrical power.

as a medium for transportation.

Another purpose is

A use that is often overlooked but is

very important is as a transporting agent to carry waste in.

From the

extent of these uses it is easy to conclude that water affects each

person •s 1i fe everyday, even

\~i thout

the 1i bera 1 construction The Supreme

Court gives the interstate commerse clause.

Although there is a hydrologic cycle, 1 in which used water is re:ycled by nature so that it can once again be put to use, there is still

2

a need to control the use of \o.Jater since nature is unpredictable and

as the population of the v10rl d increases the needs wi 11 becor.1e greater

and the possibility of contamination vlill also increase.

Since this

resource is invaluable it is not surprising that la\'IS have evolved to

maximize the quantity and uses to 'f'Jhi ch the \'later may be put for the

benefit of the most people, without undue depletion.

the need for 1aws governing the rights to

~later

i·iew

i~exico

sav.J

vJhi 1e in its infancy

and dra'rling from its historical background has developed an excellent

public water right system governing the management of both underground

and surface waters.

2.

Scope

If one morning you woke up and discovered you were completely

vJi thout \'later you VJoul d ca 11 the city uti 1i ty office or check your v.Je 11

to determine the reason for the 1oss.

If you discovered that others were

sti 11 receiving vtater but you \'Jere not, you waul d become anory because

you have just as much right to the v.1ater as anyone else.

this supposed right carne from?

~·!here

does

---

This paper will attempt to explain hm·J

rights to water deve 1oped in New r-1ex i co, and once deve 1oped hov1 they

are appropriated, regulated, and enforced.

This is intended only as a

general survey of NevJ r·1exico 111ater la\J regarding the amounts and uses

to which water may be applied.

Topics which will not be covered are;

quality of ilater, navigable v1aters, vJater economics, interstate conflicts

and compacts, Pueblo P-i gilts Doctrine, ovmership of stream beds, federalstate relations, Indian '.later rights, artesian conservacy districts,

ditches, and drainage districts.

6~14

3

3. Backqround Information

Basically, there are two quite different doctrines governing the

right to extract and use the water of surface watercourses in the

United States. 2 The doctrine of prior appropriation and the riparian

doctrine are the titles given to these systems. 3 The riparian system

originated in fuedal

land law in abundantly watered and humid reoions

'

in England, 4 thus the riparian riqhts are governed by the common law. 5

·._~

The fundamental premise of the riparian doctrine is that each m-1ner of

land bordering on a watercourse has the

rig~t

to use of the water in the

watercourse.6 Under the English Rule each landowner had the right to have

the water flow past his lands undiMinished in quantity and unimpaired

in quality. 7 Hm41ever, under the AnP.rican Rule, the landovmer is required

v

·~)

to make a reasonab 1e use of the ., ater and 1i abi 1 i ty is imposed on the

upper ri pari an 0\•lner for unreasonab 1e use. 8 The r.1aj ori ty of eastern

·'

states follow the American Rule, but some still follo\'t the Enqlish Rule.

Generally, the riparian riqht oriqinates from the physical location of

the 1and abutti nq a body of \'later, therefore a ri oari an oNner may not

exercise his ri qht on nonri pari an 1ands. lO Th e r1. par1. an

o~mer

has th e

right of use, a usufruct, in the water, as distinguished from a rioht

to the corpus of the water. 11 The right to use exists whether or not

the water is actually used, 12 and the rights may be obtained under the

COI'J'IITion la\·J of prescription. 13 The riparian riqht is measured

specific quantity of vtater,

14

by

a

but riparians are "correlative co-sharers"

in uncertain quantities.lS

615

9

4

The prior appropriation doctrine is mainly distinguished from the

riparian doctrine by its priority of right feature. 16 Appropriative

rights are governed primarily by statute and priority is usually fixed by

application for a permit. 17 In short, "first in time, first in legal

right" governs the appropriation.l8 An appropriation is defined as a

11

state administrative grant that allows use of a specific quantity of

water for a specific beneficial purpose, if water is available in the

source free from claims of others with earlier appropriations ... 19 The

appropriative right is separate from landownership and may be lost by

nonuse, but by the same token the place of use may be chanqed or the right

20

may even be sold.

Appropriation la\ts developed in the arid western

states where the rule of priority insures those \"lho have already obtained

rights to the water will not have their use of the scarce water taken

from them by a ne\'tcomer who settles or buys 1and abutti nq the watercourse upstream from them. 21

Vari9us degrees of the riparian and appropriative doctrines have

been recognized by state legislatures, and have resulted in four categories controlling the use of surface waters.

The first is "pure appro-

priation" which is sometimes called the "Colorado Doctrine." The

second is known as the "California Doctrine" which recognizes both

riparian rights and appropriation but usually limit· all new uses to

appropriation la\-'IS.

Another category is made up of riparian states that

control all new uses by administrative permits. The remaining states are

common la\'/ riparian with many statutes to helo control the water rights. 22

6_16

surrace wa"Lercourses.

1nere are many caasslTlCa'tlons or

unaer~rouna

\'tater with various tenns used to describe each. The discussion here vlill

involve four classifications of groundv1ater, 23 which must be distinguished in order to detennine which la\·t vrill be applied to each.

The first,

underground streams, is defined as a watercourse vii th a definite and kno\'m

channel buried in the ground and discoverable from the surface without

excavation, .and generally law of surface water applies to these streams. 24

The same law applies to the underflow of surface streams, which is the

subsurface portion of a \'latercourse. 25 The third type is percolatinq

\·Jaters, which are those waters \'thi ch "ooze, seep, or fi 1ter through the

soil v1ithout a defined channel ... 26 Artesian water is the fourth classification and is defined as water under sufficient hydrostatic pressure

to rise above the saturated zone 27 and is often considered to be perco1ating water. 28 These percolating waters are not subject to the laws of

surface water,29 and several different doctrines have arisen to ~overn

them. The English rule of "absolute ownership"

allo~,s

the m.,rner of the

soil to own all that is beneath the surface of his land. 30 The reasonable-use rule limits use to the needs and necessities of the owner's own

land. 31 The correlative-rights doctrine allov1s land ov1ners coequal

and proportionate rights to their overlying ownership, and does not

allow one's use, although reasonable, to reduce significantly a neighbor's

use. 32 The prior appropriation doctrine limits the use of underground

water by statute. 33

617

i

_.-J

-

~---\._..'I

.:

'"

'

I

6

I I. HISTORY AND

OE'!ELOP~~ENT

The various doctrines pertaining to watercourses and groundwater

as set out above are by no means complete, but they are sufficiently

enli9htening to understand the many theories \•lhich evolved.

Each state,

including New r·1exico, has had the opportunity to select the vrater

system it desires by legislation.

t1any states have relied on the history

in their respective areas in order to adopt the system that is best

suited for its unique needs.

f.1ost

of New r1exico•s \'later la\'t has been

held to be merely "declaratory of existing la\'.J, 1134 and therefore based

on hi story.

The earliest knrn-.:n inhabitants of the area now

as New r·1exico,

the Pueblo aborigines, were discovered by early Spanish explorers. 35 It

knm<~n

is natural ,. to believe that New Mexico's \'tater la\'1 systems were originated

by these Spaniards, but they were not.

A Spanish explorer, Espejo, in

1532-1583, tells of already existing irriqation ditches supplying the

pueblos near Socorro. 36

It is important to point out that the pueblos were

run like communes, so the inhabitants assumably shared equal responsibility for the care and use of the water system.

In 1598, Juan de Onate

placed the first Spanish settlement within the boundaries of what is

now the United States at San Juan,

Ne~r

Me xi co, and by August of that year

the Spaniards and natives began work on further development of irrigation

ditches.37 Although the natives of this area had used irrigation ditches

for both domestic and agricultural purposes before the arrival of the

Spaniards, 38 the Spanish settlers brought with them a skilled system of

irrigation.

6_18

7

Spain is believed to have received its knm-1ledge of irrigation from

the r1oors who conquered Spain in 711 A.D., and brought with them their water

laws \'lhich dated back to 2000 years B.C. vthen Hammurabi introduced

; rri qati on to improve agriculture during the Go 1den /l.ge of Babylonia. 38

The common proprietorship of water supplies, irrigation ditches, and

administration of the system by each community was an important feature

of the

r~oorish

and Spanish laws, and since this was compatible with the

native's system, the native's customs were modified but not extinguished. 39

Hhen f.'texico .. separated from Spain, and formed the f1exican Republic, the

.I

Spanish law for the most part continued in force.

This sets the stage for the estab 1i shment of the Terri tory of Nev1

Mexico from the Mexican Republic's domination. On May 13, 1846 President

Tyler declared ~~ar on ~1exico. 40 nriqadier General Kearney \'las to lead

r1issouri volunteers to take New Hexico, and his instructions \'/ere; "Should

you conquer and take possession of New Mexico ••• you will establish a

temporary civil government ••• it is forseen that what relates to the

civi 1 government wi 11 be a di ffi cult and unpleasant part of your duty,

and much must necessarily be left to your own discretion." 41 After

Brigadier General Kearney had secured New Mexico he organized a provisional

government on September 22, 1846, that has become kno\"m as the "Kearney

Code ... 42 The code states in relevant part that, "The la\'/S heretofore in

force concerning v.'atercourses ••• sha 11 continue in force. "43

A few years later on September 9, 1850, New r'1exico v1as established as

44

a territory.

One of the first acts of the legislature in 1852 provided

that all streams and rivers known as acequias (ditches) were declared to

6.19

8

.

. 45

be pu bl 1c acequ1as.

In 1880, the le9islature provided for election of

commissioners to measure the lands and regulate the amount of labor to

be performed by 1andrn·mers who shared the \"'ater from the aceoui as. 46 Various

legislative changes in 1874, 1887, 1895, 1897, and 1903 expanded

the lav1s of water rights and public O\'tnership of the \·rater. 47

It

\~tas

not unti 1 1898 that the Ne-1 t1exi co Terri tori a1 Supreme Court

\1as finally confronted with making a decision as to the type of water

48

•

f or r•~e\'1 r1·ex1co.

•

appropr1ate

In United States v Rio Grande Dam & Irriqation Co., 49 the court stated,

·

·

·

· t 1on,

·

h

s.vs t em, r1par1an

or pr1or

appropr1a

tat

~ras

,•

"The law of

p~ior

appropriation existed under the Mexican Republic at

the time of the acquisition of New

r~exi co

11

•••

and the Kearney Code con-

tinued in force all the laws of watercourses.SO. Thereby the court

adopted the prior appropriation system. The court appears to have been

convinced their,_ declaration was simply a continuance of an established

rule, for later in the opinion they add that, 11 The doctrine of orior

appropriation has been the settled law of this territory by legislation,

custom, and judicial decision." 51

How well founded is the decision of the court? Up to this point

1istory has shown that the natives, Spanish and r1exican laws purported

:o only control irrigation systems and public O\'mership of acequias.

t has not been proven that these laws were necessarily based on prior

ppropriation. 52 There are various ways the doctrine of prior appropriations

auld have developed. The court overlooks the possibility that the doc"ine may have sprung up and become the accepted custom \<ti thin the fifty

~ar

span bet\•/een the promulgation of Kearney •s Code and the adjudication

62~)

9

of this case.

If this was the situation, clearly the court's sweepinq

adoption of the prior appropriation doctrine was misfounded.

There are many possibilities as to the origin of the doctrine, but

only a feN

\~i 11

be presented here.

First, it is pass i b1e that the doc-

trine accompanied the irrigation laws of Spain as an "um·Jritten law," because if it was written in the Las Siete Partidas, 53 a Spanish code

promulgated as the law of Spain in 1348 and sanctioned in 1505, surely

a historian or an authority would have discovered it by nm-1.

there is a

po~~1bility

Second,

that prior appropriation was in effect under the

native's water system and was incorporated into the Spanish-Mexican laws.

Another theory of the origin of prior appropriation is based on

the idea that the better right was by earliest land grant from the

sovreign to old Spanish settlements or individuals. 54 A noted author

:>n water 1a"', Frank Tre 1ease, be 1i eves there is no reason to 1ook at the

>panish la\'1 because he suggests the

s~stem

of appropriation was developed

who promulgated rules and adopted customs to regulate the

1se of water to ~Jash gold. 55 If this theory is correct it would support

~miners,

he proposition set forth earlier of the misfounded reliance by the

ew Mexico Territorial Supreme Court, because the big gold rush days \"/ere

Jt until 1849. The Arizona Supreme Court apparently gave up trying to

:plain the origin of the right to appropriate and finally stated that

. ht antedates h1story

.

. SG Regard1ess of th e

1e r1g

an d even t ra d1. t 1on.

cient history and origin of the doctrine New

~·1exico

recognized the

ght of prior appropriation simply because it was a part of recent

;tory and had become the local rule and custom of the area.

621

57

/

10

As mentioned earlier, Kearney's Code Nas the first attempt to

I

J

establish laws after the acquisition of New ~1exico from the Republic

of t1exico, 58 and it was soon follovted by Ne\'1 Hexico Territory legislation. 59

Apparantly this early legislation had the effect of establishing the

appropriation doctrine because the Territorial Supreme Court in 1898

stated that the doctrine had already been adopted by legislation.6° The

authority of the legislature to adopt provisions in derogation of the

common law riparian doctrine was questioned in the case of Yeo v Tweedy. 61

The contention \·las that when New Mexico made a sweeping adoption of the

••'

common law in 1876, riparian rights became vested and that the legislature could not act in subversion of vested riparian rights. 62 The

court concluded that the legislature did not intend to adopt the riparian

system because it is not compatible with the conditions, circumstances,

and necessities of this ar.ea and that the judicial decision in 1898 in

. .

1

the Rio Grande Dam & Irrigation merely announce d a1rea dy ex1st1ng

aw. 63

t

The court therefore he 1d that New r1exi co had never adopted the riparian

system. 64 The dissent by Judge Parker is interesting in that he points

out the water in question in this case was situated in the eastern part

"1

of New

~1exi co

which was acquired from the Repub 1i c of Texas Nho had

•

65

adopte d the riparian doctr1ne.

Hhen the question of appropriation came before the Supreme Court of

the United States their analysis was similar to the territorial courts but

it had an additional basis. The Court recognized the need for appropriation

of flowing waters for mining purposes and agriculture in the reclamation of arid lands but based its decision on the Homestead Act of 1866

622

66

11

and the Desert Land Act of 1877

67

which in effect recognized the local

68

customs, laws, and decisions in respect to prior appropriation.

As a sidenote, it is interesting that in 1935 these Acts were held to

have conveyed all the non-navigable waters to the states and thereby

,,....;

subject to the states' plenary control, but in 1955 it Nas held that the

Acts were not applicable to reserved lands by the United States; the

result has been confusion in the determination of Federal-State rights to

69

govern water.

In 1903, the Supreme Court of the United States recognized that the

waters belonged to the public and the legislation of a territory, as

well as a state, is sufficient to regulate the use of water.70 Subsequently the courts reinforced these judicial decisions by stating the

judicial detenninations did not make the law, they 11 0nly recognized the

law as it had been established and applied by the people" through

custom. 71 Furthermore those courts stated that the type of appropriation

adopted in New Mexico was the pure fonn or 11 Colorado Doctrine 11 of

appropriation,

72

in \'lhich application for a permit to appropriate \'later

must be submitted to the state and it is only upon approval that one

can appropriate \'Ia ter to a beneficia 1 use.

Prior appropriation became the custom of this area because of its

hot arid climate in which rainfall is minimal and temperatures are high

73

juring the summer months.

Settlement and econ~mic development of this

·later-deficient region was dependent on successful farminq by irrigation,

;uccessful mining, and sufficient municipal water supplies, which in turn

74

~ere a11 dependent on the rf ght to di vert and aPP ron ri ate 1·1a ter. The

riparian riaht of continued streamflo"'' and use beino limited to the stream75

)ank \'/ere not suitahle for irriqation purposes.

The cnurts in New r·-1exico

.J

623

12

have relied heavily on the custom and local rules, which were already

in effect to uphold legislation which provides prior appropriation on

the grounds that it is merely declaratory of existing law •

.,,.

jn 1907 a comprehensive act on surface water regulation was passed

the legislature and it is the basis for the current statutes on surface

waters. 76 In 1931 the first statutes that passed constitutional muster

were adopted which pertain to regulation of underground water. 77 The

by

s i gni fi cance of \'later 1egis 1ati on in New Me xi co today is evident by the

598 pages of legislation and additional pages of rules and regulations. 78

The Constitution of the State of New Mexico was adopted on January

21, 1911, and the territory achieved statehood on January 6, 1912.79

The framers, aware of the importance of v1ater and its distribution,

devoted Article XVI to "Irrigation and Water Rights.''

It recoqnizes all

existing rights to the use of water as long as the use is for a beneficial

purpose;BO states that beneficial use shall be the basis, the measure, and

the limit of the right to use water;82 authorizes the legislature to

make laws pertaining to drainage districts and systems;83 and a 196~,-

amendment allows trials de nevo.84

Ne\I'J

~1exico,

throuqh the wisdom of the framers of its Constitution

and its legislatures, has provided a prior appropriation system regarding

both the surface and underground waters.

The courts have zealously

defended the prior appropriation system based on shaky history and a

strong custom, as well as recognizing it is the best suited doctrine

for their climate.

624

'

.. -

13

I I I.

P.PPROPP-IATION OF '·lATER

Through history the surface \t!ater itself has belonoed to the

..

·'

community or public, as already noted.85 The early territorial legisla. .d

tion perpetuate d t h1s

1 ea, 86 and the framers of the New Mexico Con-

stitution provided that the "l·1ater of every natural stream, perennial

or torrenti a1, within the state of

N~w

\1exi co, is hereby rlecl ared to

belonfl to the public ••• u87 Hhen challenged, this Constitutional provision

was upheld

as

only "declaratory of prior existing la~·."88 Since this

.I

provision only referred to surface waters, it was soon asserted that

specific mention of surface waters amounts to an exclusion of all other

waters by negative implication. 89

In Yeo v. T\'Jeedy90

private m·mers of lands overlying the underground

water basin were arguing they had a vested property rights in the corpus

of the ground\a1ater \'Jhi ch was incident to their ownership of 1and, and

since this vested property right antedated the enactment of the Constitution

or legislation pertaining to groundwater the enactments violated their

vested property rights.91

The leqislation referred to stated:

"All

waters in this state found in underground streams, channels, artesian

basins, reservoirs, or lakes, the boundaries of which may be reasonably

ascertained ••• are hereby declared to be public waters and to belong

to the public.u92 In a len9thy opinion the court rejected the claim of

absolute ownership under the doctrines of "capture," "reasonable use,"

or 11 Correlative rights," and once a9ain depending on history, custom, and

625

14

the arid climate decided both the statute and the Constitution were only

"declaratory of existing law." 93 Amazingly enough the court declared

the 1927 groundwater statute to be technically void because it enlarged

the jurisdiction of the state engineer, but still held that the groundwater

in the artesian basin \'Jas subject to appropriation even without the statute •

A later statute95 cured the consitutional defect, \IJaS upheld by

.I./

judicial decision, 96 and is still a part of the current statutes. 97 A

1953 statute, 98 hm~Jever, declared "all underground waters to be public

\'laters and subject to appropriation for beneficia 1 use. 11 The two current

statutes are_, seemingly contradictory in that one states "Only underground

waters within reasonably ascertainable boundaries are public," 99 and the

other states that "all underground v:aters are public,"

-

100

They are only

distinguished by the fact that the first requires approval of application

to the state in order to apply the water to a beneficial use 101 while the

latter does not. 102

A question arises as to which statute is applicable to percolating

water and underflow of a surface stream. As long as the percolating

water is close to or above an area that has been declared to have a

reasonably ascertainable boundary, the construction of the first statute

103

will probably be broad enough to include it. After all, if the court

will declare an artesian basin to be public water subject to appropriation without a valid statute, 104 it will likely incorporate percolating

waters into a new valid statute. Most western states, who have had

occasion to rule on the laws applicable to underflow of a surface stream,

626

94

15

agree that this water is subject to the same laws as the surface stream

105

waters rather than groun~1ater.

Even though it is generally said that all the waters of the state,

106

both ground and surface water, belong to the public,

there is some

water that is not or may not be public. There is a questionable classification of water that appears to be excluded from public ownership by

Constitutional provisions. Article XVI, section two of the Nev1

~1exico

Constitution states, "The unappropriated \"'ater of every natural stream

•••

is hereby declared to belong to the public and be subject to appropriation

for beneficial use, in accordance \•tith the laws of the state. Priority

of appropriation shall give the better right,nl07 and section one provides,

"All existing rights to use of any waters in this state for any useful or

beneficial purpose are hereby recognized and confinned.ul08 By using the

phrase, "unappropriated water," 109 the framers may have been reiterating

their recognition that some of the \'laters had a1ready been appropriated

as stated in section one. 110 However, it seems that these waters which

_..

were already appropriated prior to the adoption of the Constitution are

excluded from pub 1i c m·mershi p, and therefore v1oul d not be subject to

the appropriation la\'IS of the state.

If this proposition is proven true

it \'lill raise many issues as to the rights of the private m·mers of these

prior existing water· rights to transfer, divert, store, or use these

waters for whatever purpose they desire free of state controls.

A special statute lll controlling ownership of artificial surface

water codifies the result in Hagerman Irrigation Company v. East Grand

Plains Drainage District,ll2 which states that artificial surface water

\'lhi ch is created by man is the persona 1 property of the

m~ner

as 1ong as

it is confined to his land but once it is deposited in a stream it becomes

627

16

subject to public ov:nership, and the appropriator of water from that

stream cannot require the cant i nuous flow of such \"Ia ter to the stream. 113

Artificial surface water is defined as those waters "due to escape, seepage, loss, waste, drainage, or percolation from constructed works

•••

which depend for their continuance upon the acts of man."ll4

~1ost

springs are public but \"later \•lhich comes from a natural spring

and does not establish a definite channel but sinks into the soil is

personal property and not subject to appropriation.ll5

The public does not have continuous ownership of the water throughout

its hydrologic cycle.

There must be a point at which the public gives

up their ownership, othen,lise everything that has water in it, such as the

plants, animals, clouds, and human beings, would be subject to ownership

by the public.

The point in time of change of O\·mership is compared to

fish in a stream:

They are not subject to private ownership until caught.

116

Likewise, once water is impounded and reduced to possession by artificial

means it becomes personal property, and may be subject to purchase, sale,

or even larceny, no matter what it is to be stored or transferred in. 117

However, thirty years later the court held that although water from tv'o

streams had been artificially impounded by a dam, it remained public

\"'ater unti 1 there was actua 1 appropriation of the water by both diversion

and application to a beneficial use. 118

'

The court did not say and it is ,.~ ,,'-~

.\ :.

·~

. "' !

not clear whether this later case overruled the earlier one, and there are

~o

statutes \'lhich address this subject.

The two cases may be distinguished

1 a major point, in that the defendant in the earlier case was demanding

1

rep~innan right to the continuous flm·J of water in the stream, 119 but

n the second case all that was being requested was the right to fish

n a reservoir.

120

In both cases the dam \'las built directly on the stream.

628

\,.....

'-

17

This leaves open the question of ownership of water once it is impounded

by artificial works without a true diversion from the stream. The first

case would appear to allow

person~l

ownership of the water because it had

been artificially impounded, but the later case appears to require an

actual application to a beneficial use.

In summary, most water is owned by the pub 1i c but it vii 11 become

personal property when it is diverted from the stream.

If there has

been no true diversion the time of personal ovmership is in conflict.

629

18

IV. THE APPROPRIATIVE Rif,HT ('·JATER RIGHT)

1. Nature of the Right

Long ago Kinney, a noted author on water rights and irrigation, defined a v1ater right as The exc 1us i ve independent property right to the

11

use of water appropriated according to the law from any natural stream,

based upon possession and the right continued so long as the water is

actually app 1i ed to some beneficia 1 use or purpose. ul21 The tenn water

right may be somewhat of a misnomer because the right is not to specific

water flowing in the stream; it is simply a right to take and use the water.l 22

The corpus of the water in a stream belongs to the state in trust for the

pub 1i c, but the right to its flow and use is a property right kno\'tn as a

usufruct or a usufructuary right or water right. 123 The \A/ater right is

generally considered to be real property, and is usually a private right

rather than belonging to the public like the corpus of the water.l24 Naturally the water right is an "exclusive right \-Jhich distinguishes it

11

from vipari·anism.l25 The New Mexico Supreme Court has decided the water

right is a freeheld interest rather than just a possessory interest,l2 6

but note that this freeheld interest is conditional. It is an incorporeal

hereditament, solely usufructuary,l 27 but it is not an easement because the

appropriative right is distinct and exists independently apart from the

ownership of the 1and. 128 The water right a1so is dis ti net from the property

rights in canals, ditches, pipelines, and reservoirs by which the water is

Hverted. 129

The general rule that the appropriative right is appurtenant to the

articular land in which the water is applied to a beneficial use,

as recognized by an early case in the federal court,l30 which is not

fnding precedent on the state courts.

Twenty years later the New Mexico

IPreme Court adopted this rule after citing a Texas case as authority. 131

630

19

In between this time period the Court had held that a riqht to use water

for raising livestock on qovernment land was not necessarily appurtenant

to a particular section of land.l32 These cases may be distinauished by

the fact that one case involved qovernment lands so the use of the water

was only a possessory riqht,l33 whereas in the other case the 1and \Alas

private and the use of water was an incorporeal hereditament to a freeheld interest.l34

A statute now provides in part that:

11

All water used in this state for irrigation purposes ••• shall be

considered appurtenant to the land upon which it is used and

the right to use the same upon said land shall never be severed

,/

from the land without the consent of the owner of the land, but

by and with the consent of the owner of the land, all or any part

of said right may be severed from said land, and simultaneously

transferred, and become appurtenant to other land, or may be

transferred, for other purposes, vJi thout 1os i ng priority of right

theretofore established ••• ul35

An earlier statute with siMilar wording was upheld by the Court,l36

and more recently the Court has stated that this section on surface water

and another section on aroundwater expressly recognize that water

ri~hts

on certain lands may be severed from those lands and become appurtenant

to other 1ands or even transferred for other purposes and uses. 13 7 HO\'Iever,

if title to the land with the appurtenant water riqht is transferred the

title carries with it all of the water rights for irrigation purposes un1ess the water right is expressly reserved. 138 The consent of the ovmer

11

of the land 11 has been construed to include a written election by remaindermen before severence of the water right may be perfected.l39 These sectionsl40

only apply to the use of water for irri9ation purposes and do not touch on

631

20

whether or not use of water for domestic, industrial, or stock raisinq

purposes is appurtenant to the land or if it can be severed from it.

Before continuing it is important to reiterate a few basic points of

the character of the appropriative right in order to distinquish it from

other property rights.

First,the water right is not the right to the corpus

of the water in the natural stream, or in the underqround basin; it is

sinply the right to take and use water for a specified purpose.l41 The water

right is also distinct from the property right in the canal, ditches, pipe1i nes and reservoirs by \'thi ch the \'later is carried to the 1and it is to be

used on.l42 Third, the water riqht is appurtenant to the land and is severable from thi-irrigated land on which the water is to be put to beneficial~use.l43

2. Acquisition of the Right

The cornerstone of the appropriative system is the maxim that at beb1een

appropriators, priority of application shall give the better riqht. This

maxim is so important it was included both in the Constitution 144 and in

statutes, 145 and was reco~nized by judicial decision as early as 1900. 146

This rule of "first in time, first in right"

fonnulated by custom. 147

'tJas

prompted by necessity and

There are two main ways to acquire an appropriative riqht.

method of

ac~uiring

The current

the right to beneficial use of water is by application

to the state en0ineer for a permit to aporopriate, but note the application

fonns are different for surface water148 and groundwater. 149 The state

engineer may

re~uire

detailed information as to the amount of water to be

used, time period of annual use, the use for which it shall be applied, etc.,

and even maps, olans, and specifications. 150 If the applicant follov:s all

the statutory mandates and the right is eventually granted by the state

engineer, the priority claim relates back to the date of the receipt of

the application in the state engineer's office. 151

632

.

__,

21

The other method of acquisition of water rights is protected by the

Constitution by its confinnation of "all existing \'later rights" for a

beneficial purpose. 152 The statutes declare that "Claims to the use of

\~ater

initiated prior to r1arch 19, 1907, the right shall relate back to

the initiation of the claim." 153 These existing water rights are also

154

and to community ditches which were already

recognized in ground\'Jater,

constructed. 155 Also, the existing vested rights and priorities in

construction of reservoirs, canals, pipelines, and other \'larks \'lhich

were commenced before t1arch 19, 1907 are recognized. 156 The methods of

. ., OT th ese ves t ed r1g

. hts are s1m1

. .1 ar for sur f ace waters 157

dec 1ara t 1on

158

and groundwaters.

.The statutes require a prior actual appropriation

for beneficial use, 159 but do not require the appropriation to be conL"

tinuous. The forfeiture statute, 1GO may not apply to failure to beneficially use the water in question because it applies only to the ri9ht

which has been "appropriated or adjudicated" and furthemore requires

notice from the state en9ineer.

It appears that this right cannot be

forfeited and there has been no case on the possible abandonment of a

vested right prior to 1907.

The most extensive adjudication in the area of existing water

rights prior to 1907 is based on the "Doctrine of Relation" or relation

back. The doctrine was recognized as applicable to appropriative rights

in 1883, which was prior to any statutory provisions. 161

,-

later it \"las

'

noted as being universally applied by courts in avid

states in the

appropriation of water, but that it does not apply if the intending

appropriator does not use reasonable diligence in prosecuting his work. 162

Statute now provides that the right shall relate back to the initiation

633

22

of the claim was prior to March 19, 1907, and if after this date it

shall relate back to the date of receipt of the application with the

provise that the application is subject to compliance with other

provisions of the statutes. 163

The case of

Fa~er's

Develonment Comoanv v. Ravade Land and

Irriqation Comoanv, 164 presented the question of who had the prior

• 1-'

right when the defendant started his work before the plaintiff started

his and also before the 1907 statutes

~ere

-

enacted although he did not· '

complete construction of his ditches until after the enactment of the

statutes at ·which roint the plaintiff had filed for appropriation under

the tenns of the statutes. 165 The Idourt concluded that the claim prior

.

to the enactment of the statutes related back to the initiation of the

'')

work and was superior to the claim initiated under the statutes which

only

relat~d

back to the date of filing the application rather than to

initiation of the works.l66

In 1961 , the NeVI t1exi co Suprer1e Court he 1d that the statute a11 m~Iing relation back was only relevant to surface waters but the legislative intent allo'IJed expansion of the doctrine to grounm1aters. 167

~

However, the court did not distinguish the relation back to the filing

of the application under the act and the relation back to the initiation

of the actua 1 work prior to the act, therefore the Court a11 O\'!ed

relation back to the initiation of the work. 168 The possible reason the

court allm·Jed relation back to the actual work instead of filinq of

the application leads into the next topic.

The reason is that the

application was not required for the area v1here the groundv1ater

located.

634

\•las

S

., .

,.

23

3. Water Subject to the Appropriative Pight

Not all v1aters are subject to appropriation, and brief surrmary of

these waters fo 11 0\'IS.

As noted earlier' 1()g both statute 170 and case

1aw171 provide that artificial waters are not public waters and are

thereforP- not subject to appropriation.

Underqround \'raters thnt have

reasonably ascertainable boundaries are public and subject to appropriation for beneficial use 172 upon approval of an application, 173 but

underground water that is not within reasonably ascertainable boundaries

is public and subject to appropriation for beneficial use but no app• t 1on

•

• .,, requ1re

• d • 174

1s

11ca

• /.

Jnappropr1ated water II belongs to the pu b11c

and is subject to appropriation for a beneficial use, 17 5 but the prior

II I I

•

existing appropriative ri9hts may not be subject to state controls.

Stock owners who build water tanks or ponds which have a capacity of ten

acre-feet of water or 1ess and are bui 1t to capture surface \·taters for

the purp~se of watering stock are exempt from the statutory requirements. 176

Note that the use to

~rhi ch

grounm1ater wi 11 be put may be the deciding

factor in whether or not an appropriative right is required.

If the

--)

water is to be used only for watering of livestock, or irrigating non/

commercial trees, lawn, or garden or use for household and other domestic'

purposes, mandatory language, "shall," requires the state engineer to

issue a permit to the applicant. 178 Now that it has been explained

~1hat

water is subject to the appropriative right and VJhether or not an

application is necessary, the next focus of our discussion \•till be upon

the conveyance of this appropriative right.

635

24

4. Conveyance, Transfer, and Change of Puroose

Since the water right is aprurtenant to the land, the transfer of

title of land in any manner carries with it all the water rights appurtenant thereto for irrigation purposes. 179 There is a possibility,

however, that the water rights will not accompany the land title if

they have been "previously alienated in the manner provided by lavt." 180

\

'

I.·-

There are three statutes that allow surface water riqhts to be alienated

from the 1and. 181 The first pro vi des +"or the severence of the ,-.,ater

right from the land if certain requireMents are met. 182 These requirements are a·s follo~Js:

(1) consent of the landovmer; (2) changes can be

made without detriment to existing rights; and (3) approval of the

application by the state engineer a+"ter the ovmer gives notice by

publication. 183 The transferee receives the same priority of right

184

established by the transferer.

The second laHful method of severence

I

is for the appropriator to chanqe the purpose of use of the water or

change the place of diversion upon approval of the state engineer.l85

This in effect a11 ows a trans fer of the \··tater rights for other purposes

and uses.l86 The rationale for this transfer is based upon the inherent

right within the water right as property to change its n1ace of diversion

or use as lonq as other water users are not impaired by the change. 187

The third method is simply an extension of the previous one but it eliminates the procedural requirements when there is an emergency, such as

crop loss.l88 Water for storage reservoirs is exempt from the prohibition

on the transfer of ownership or assignment of a vtater

ri~ht

by special

provision.l 89 These statutes obviate the subjective factual question of

the intent of the owners to transfer the water ri9ht which presented a

190

Problem in an earlier case.

636

25

The water right in under9round waters can likewise be transferred.

Again, the change of location of the well or change in use of water is

subject to the state engineer's approval upon a sho\'Jing that the change

vtill not impair existing rights and the proper procedures are followed. 191

The application must include a description of the present and nroposed

well locations, description of the land the water rights are trans~erred

from and transferred to, 192 and if only a portion of the water riohts are

transferred the lands must be surveyed· and maps prepared. 193 A license

is necessary to appropriate Nater for the new place or use, 194 hut no

license is necessary \·then replacement wells 195 or supplemental wells 196

~·

are involved.

Generally since the water right is real property it cannot be transferred to someone e1se except by a written instrument. 197 The New t1exi co

statutes expressly provide that any permit or license can be assigned if

-!>.

done so by one of the methods set out above, but they also demand that

in order for the assignment 11 to be bindin9, except to the parties

involved, it must be filed for record in the office of the state engineer.ul98

It is generally accepted that a \·later right itself may be mortgaged and

it is also subject to the mortgage on the land that it is appurtenant to. 199

Speci a1 provision a11 ows the o\'mer of a \'later right to 1ease a11 or

any part of it 200 upon approval of application statinq the use and location of use to which the water will be put. 201

5. Elements and Limits of the Right

There are many historical, statutory, and judicial limits and

elements placed on the right to use the water.

637

The origin and reason

26

for these limits and elements lies in the necessity of this arid reqion

for the maximum beneficial use of the scarce water supplies;

these

liMits are inherent in the prior appropriation system in order for it to

be effective.

Priority is the first element and also acts as a limit.

The Constitution sets out the basic rule that ''Priority of appropriation

shall give the better right." 202 This languaqe is also echoed in the

statutes. 203 The various methods of acquiring the aporopriative right

have been discussed.2°4 There are basicly two classifications for

acquiring priority.

Claims of water rights prior to

r~arch

19, 1907

have a priority date as of the time the water was actually put to a

beneficial use.205 Those claims after ~1arch 19, 1907 have a priority

date based upon receipt of application in the state engineer's off{~e. 206

The significance of the priority date Pill be discussed later, 207 but

"""

let it suffice for now that in years of draught

what little water that is

available goes to the appropriator

~lith

the earliest priority date.

The main restriction and element of the appropriative right is

placed on the use of the \'later.

--

The Constitution declares, Beneficial

11

use shall be the basis, the measure, and the limit of the right to the

use of water, .. 208 and that public waters are 11 Subject to appropriation

for beneficial use ... 2° 9 Like'.-tise, the language of beneficial use permeates the statutes for both surface 210 and ground\~ater.211

The application of water to a beneficial use is the sine gua non of

a water right under the doctrine of prior appropriation, 212 but there is

little guidance as to what will be considered a 11 beneficial use." The

statutes do not make an attempt to define beneficial use, but various

provisions may be applicable in determining some of the uses the legislature believes fit within the term.

A statute pertaining to underground

638

. 27

water uses mandatory language in requirin9 the state engineer to issue

a pennit to anyone who applies for the use of \·tater for v1aterin9 livestock,

for i rri gati on of not to exceed one acre of non-commercia 1 trees, 1awn,

213

or garden or for household or other domestic uses.

The state engineer

may issue permits on a temporary, basis for prospecting, minino, construction of public works, highways and roads, or drilling operations

designed to discover or develop the natural resources of the state.2 14

Statutes also impliedly recognize irrigation,215 industrial purposes, 216

and county \"later supply systems217 as beneficial uses •

.-'

Case la\1/ only slightly enlar9es the realm of beneficial uses. The

attainMent of state conservation purposes,218 huntinq, fishin9, and recreation,219 and Pueblo Rights (city or municipal rights to water),220 have

I

been recoqni zed.

r

The use of Nater for qenerati on of e1ectri ca 1 power has

not yet been decided.

The determination of \!-that constitutes a beneficial

use will be resolved on a case-by-case basis considerin9 the totality

of the facts. 221

The arid region doctrine \'lhich states that beneficial use, as to

both quantity of water and periods of time of use, is the measure of

the right, \'Jas modified by statute.222 In Harkey v. Smith, 223 the limit

of the right to beneficial use was determined to be set by grant or

permit from the state engineer, 224or decree of the court. The reasoning

behind this decision is that the Constitution merely declares the "basis

of the right to the use of water, and in no manner prohibits the regulation of the enjoyment of the right" and furthermore the doctrine of

seasonal appropriation is not well adapted to

~eneral

aqriculture be-

cause it \'lould limit the fanner to growing only one crop year after

Year.225

639

.r:.

·. '._}

28

The power of the state engineer in granting a permit is solely

to detennine if there is unappropriated Nater available and if so,

to set the time for completion of the project within five years and actual

aoplication of water to beneficial use within four years after completion of the project. 226 Upon inspection of the project the state

engineer shall issue a license to the m·mer of the permit to "appropriate

water to the extent and under the condition of the actual application

thereof to beneficial use.n227 The point is that the state engineer does

not have the power to determine if the use is a beneficial use, he can

only grant the permit or license based upon the application.

Thereby

the courts are 1eft with detenni nation of what is or is not a beneficia 1

use. It appears that beneficial use would be a fact question for the

jury's determination.228 The courts state they are the only ones under

New

~1exico

]av1s that are given the pm·rer and authority to adjudicate

.... ·.) ~·

,.

·,

... ,;

.~·

water rights,22 9 and the state engineer concedes that he does not have

the authority to adjudicate \'-later riqhts. 230

The significance of the term"beneficial use .. is obvious in that it

•

1s

I

used to describe three important aspect of the right; the basis, the

measure, and the limit.231 First, beneficial use is the basis of the right

to use \-tater.

This distinguishes the appropriative ri9ht from the

riparian right.232 The right to use of water in the appropriation system

in New Mexico does not depend on the location of the land owned, instead

it is generally based on priority of application to a beneficial use.233

Beneficial use is the measure of the right to use Nater comprises

:he second aspect.

The quantity of \'later allowed to be used is distin9-

---~

29

uished from the amount beneficially used.

For irrigation purposes the

state engineer or court is to allovJ only the amount of water v1hich will

result in the most effective use of available water that is consistent

with qood agricultural practices in order to prevent waste. 234 The

idea is to only

allo~t

the amount that can be beneficially used.

Even if

the amount allowed is greater than the amount that is needed, the

appropriator can take only so much water as he can beneficially use. 235

An attempt at explaining the quantity of beneficial use has resulted

in this definition:

for

"The amount of \/ater necessary for effective use

1

to which it is put under the particular circumstance of

the·~urpose

soil condition, method of conveyance, topography, and climate.u236

As nebulous as this sounds it is clearer than the standard definition

\'lhich states:

"Beneficial use as determined by our courts is the use

of such water as may be necessary for some useful and beneficial purpose in connection \•lith the land for which it is taken.n237 In a fairly

recent case the Court opined that the amount of water necessary for

cultivation of the land, called "duty" of water, should be detennined

by the following essential factors:

(1) amount of water diverted; (2)

place of diversion as related to use; (3) amount necessary for a particular crop or land; {4) season of the year; and (5) general irrigation

water-using practices followed in the area.238 Although the statutes239

set out the basis for allowance of water rights for irriqation, the

'('"•li ._,

court must have thought these guides were too broad and the factors

above are in the

fonn;~

of a strong suggestion to the state engineer of

\-!hat he should consider in arriving at an allO\'lance.

Although these

30

factors are to detenni ne the duty of \'Jater, the purpose of setting the

duty is in effect to set the maximum possible beneficial use.

The last aspect is that beneficial use is the limit of the right to

the use of water.

This aspect is closely related to the measure of

the water right, so the discussions may somewhat overlap.

The standard

measurement of the volume of water is the acre-foot,24J and up to three

acre-feet per annum is allowed for beneficial uses such as domestic

needs, stock watering, and irrigation of not more than one acre of lawn,

noncommercial trees or garden.241This is an example of beneficial use

being the limit of the right to appropriate water, because although the

~

appropriator is a11 0\'led up to three acre-feet (one acre-foot is equi va 1ent

to 43,560 cubic feet242), he may only use the actual amount that is put

to beneficia 1 use, even if the quantity a11 owed· exceeded the amount

beneficially used.

The converse of this statement, ho\'Jever, is not true,

i.e., the appropriator cannot put to beneficial use more water than he

has been allowed.

The \'later right for irrigation purposes is explicitly

limited to the amount beneficially used 11 and the amount allowed shall

not exceed such amount ... 243

A pair of cases that date as far back as 1914 recognized that beneficial use was the limit on the water right.

In State ex rel. Communitr

Ditches or Aceguias of Tularosa Townsite v. Tularosa Community Ditch Co.244

The Court pointed out that it is only by application of the water to a

beneficial use that water is allowed to be used at all, so an appropriator

can only have a water right to so much of the water as he applies to

beneficial use. 245 The court in Snow v. Abalos 246 makes it clearer to

understand by stating:

11

No one is entitled to waste water, when his

642

31

requirements have been satisfied, he no longer has a right to the use

of \•later, ••• "247 A landmark case, State ex rel. Erickson v. ~kClean, 248

was decided in 1957, which aided in clarification and importance of

beneficial use as the measure and limit of the water right.

Underground

Hater from an artesian basin was being used from a well to irrigate the

land

r~r. ~~cClean

0\Amed before 1919 but since that time the \'tater had

been a11 O\'led to fl 0\'/ out on 250 to 300 acres every \"!inter to make fresh

water for horses and irriqate grass for the horses.

In 1940 a pump was

put on the well to control its flow, and the land was cultivated for

farming.

The state engineer brought suit asking for injunctive relief

because the \'later right \'las forfeited and because use of the \":ater \'..Jh i ch

constitutes waste is not beneficial use. The court concluded that

"no matter ho\'J early a person's priority of appropriation may be he is

not entitled to receive more v1ater than is necessary for his actual use, ..

and that waste is not a beneficial use, so no right can be acquired in

this excess water that is wasted. 249 The court distinguishes this case

from those which allow irrigation of native grasses by stating it is

the method of watering here that is wasteful and a non-beneficial use,

and states that use of the water must not only be beneficial to the lands

of the appropriator, but it must also be reasonable in relation to the

lands.250 The impact of the requirement of the reasonableness of beneficia 1 use has not been detenni ned by the New Me xi co courts, hov.,rever,

they may find the California Supreme Court's construction of the terms

to be persuasive. The California Court has stated that what may be a

6·13

32

reasonable beneficial use where water is present in excess of all needs

would not be a reasonable beneficial use in an area of great scarcity and

need, and that what is beneficial use at one time may, because of changed

conditions, become a waste of water at a later time.251

Should the New

Mexico court follow the California Court's lead, there would be a Constitutional question as to whether or not the added requirement of

"reasonableness"\\•ould be an attempt to divest rights accrued under the

Constitution and whether the minimum rights afforded the public under

the Constit_ution could be minimized even further.

There could also be

.i

the possible question of "separation of powers" since the addition of

reasonableness, if constitutional, should be within the realm of the

legislative responsibility rather than judicial.

The appropriative right to water cannot be acquired simply by puttin9

the water to a beneficial use; there are other requirements that must

also be met.

In 1900, the courts noted that diversion is a necessary

element to a legal appropriation,252 and in 1926 the element of intent to

apply the water to a beneficial use was injected. 253 In 1922 the court

was asked to reconsider the requirement of a diversion in the case of

State ex rel. Reynolds v. Niranda. 254 Lorenzo t-1iranda allm1ed his cattle

to graze in a wash that flowed intermittently across his property, and

he would cut and store the grass in the fall season for winter use. The

court

~tas

urged to adopt the Co 1ora do vi ettl that required only the intent

to use the water and actual application of the water to a beneficial

use.2S5 Instead the court followed an early Nevada case, 256 and held

that to constitute a va 1i d appropriation of \'later in New

t~exi co

for

33

agricultural purposes, there must be a man-made diversion, an intent

to apply water to a beneficial use, and actual application of water to a

beneficial use. 257 To these requirements the statutes add that if construction of \'IOrks is necessary to acquire a license the state engineer

can set a time limit in the pennit, 258 and construction of the \·torks must

be diligently prosecuted. 259 The diversion requirement serves the three

following purposes:

(1) it provides objective proof of intent to

appropriate the \·Jater for beneficial use; (2) diversion is a practical

notice to others on the stream that a water right is being asserted;

and (3) there is an assumption that dedication of water to uses \':hich

require diversions will result in better allocation of resources. 260

./

P~l though

the concept of "beneficia 1 use" is fundamenta 1 to the

doctrine of prior appropriation and diversion is not 261 (as noted above

in the Colorado law), the concept of diversion has raised many questions •

....

Earlier discussion on the determination of whether water is publicly or

privately ovmed revo 1ves in 1arge part on whether or not there has been a

diversion.262 Another problem, change in the point of diversion, has

been the topic of many cases. Statutes were drafted to help resolve the

issue. 263 It tlas consistently been the rule regarding surface \oJaters

that a "water right is a property right and inherent therein is the right

to

change~the

place of diversion, storage, or use of the water, if the

rights of other water users will not be injured therebi~

264

There are

substantial restrictions in this rule in that other water users must not

be injured by the change in point of diversion, and the statutes require

an application be submitted and approved by the state engineer. 265 There

is relief provided from all the procedural aspects of application if the

state engineer finds an emergency exists because a delay would result

645

34

in "crop loss or other serious economic loss'' to the applicant" and if the

state engineer further finds that "no forseeable detriment exists to

rights of others having valid and- existing water rights."266

Cases 267 and statutes 268 apply similar requirements to ground\•!ater

for the change of location of a well. The statutes governing change in

point of diversion 269 or change in well location 270 do not qrant; rather

they restrict the right of an appropriator to change his point of

diversion or \11'ell location. 271 The applicant is not required to prove

. t ed wa t ers ava1"1 abl e272 because a change 1n

. po1n

. t

t here are unappropr1a

of diversion' or well location is not an attempt at a new appropriation, 273

'

'

\

therefore although there is a change the appropriator retains his priority

date. The applicant does have the burden to prove that the change will

not impair existing rights of others. 274

The question of impairment has led to significant liti9ation.

The question of impairment depends on the facts of each case275 and is

to be determined by the state engineer. 276 Upon a finding of impairment

there is no need for the state engineer to determine the degree of

impairment. 277 The state engineer does have the authority to approve an

application subject to condition in order to prevent impairMent. 278 The

lm•1ering of the \'tater table is not per se inpairment. 279 In the case

of City of Roswell v. Berry,2 80 the state engineer determined that the water

table would be lo\o'lered 0.16 feet \'lhich would have onl.Y a "negligible

effect" on the chemica 1 qua 1i ty of Berry's

\'Ia ter,

was no impainnent of Berry's water riqhts. 281

and therefore there

Later the case of In re

City of Ros\'lell282 involved the desires of the city to change well location from \•:ells with high salinity to wells with low salinity. The Court

616

\

-.•...,'

'

---

35

held that although the quantity of appropriation Nould be the same, the

point of the new \"tells would cause more salinity for irrigating appropriators, and that an increase in salinity results in decrease of yield

per unit of water used; thus, other appropriator's riqhts were impaired

even though the city offered to reduce its quantity of rights by 25%. 283

These two cases have inserted the issue of quality of the water rather

than just quantity of the \'later, so the decision of the state engineer

as to impairment involves many factors other than just the amount to be

used.

.~-

Although there were emergency provision statutes for surface waters,

the court would not find implied authority of the state engineer to

issue emergency permits for change of well location in the absence of

statute pertaining explicitly to orounm~aters.284 A year later three

statutes

I

\'tere~enacted

to allow reolacement wells and supplemental wells

to be drilled without waiting for publication and hearings if an emergency existed.285 These statutes are interesting because they allow the

drilling to be performed before or after some preliminary procedures

depending on whether the rep 1acement we 11 is within one hundred feet of the

old \'Jell , 286 or if it is greater than one hundred feet a'~ay, 287 or if

it is a supplemental \'lell.288 A unique tl"tist is added to the first statute

mentioned above because other water users are provided the remedy of

289 d f th

•

. . th e dr1"11 1n9,

.

damages rather than be1ng

ab1e to enJ01n

an ur ermore ,

the state engineer is not even required to make a finding as to \."thether or

not there is impairment prior to the drilling.

36

Another question which has arisen from the act of diversion

revolves around storage works and distribution of water through water

Norks. Hells Hutchins traces the "puhlic acequia" (coJ11Tiunity ditch)

back to irrigation and domestic needs of the early natives and Spaniards. 290

The communities would elect a mayordomo (superintendant) to manage the

distribution of \·later and repair of the ditches in vthich everyone was

required to contribute labor and materials. 291 In these early times the

.

waten~orks \\~ere

ovmed as tenants in common by a11 who jointly use: the

water therefl','om, 282 but rem~~b·e·~~hat ovmership of the ditch is separate /

\._______

and distinct from ownership of the water or \'later right.

The result of

this was that community acequias were held to belong to the public and

i,,./

293

thereby under regulation of the state.

In 1900 it was already recognized that ditches, other than community acequias, for diverting, carrying, delivering, and distributing water could be owned and operated

by a non-consumer.294

In 1923, joint ownership of the ditch by owners

of water rights as \'/ell as ovmership by an independent person or cor-poration who contracts with the \\later right owners to bring them water

were recognized.295 Thus, there are at least three types of irrigation

works ownership- public, private mutual, and private independent.

The statutes provide that a person, firm, association, or corporation can be the owner of \•tater works and the term 11 \'later works" includes

canals, ditches, flumes, aqueducts, pipelines, acequias, reservoirs, or

other works. 296 Uhere owners have the ri qht to use of the works and one

neglects to do his share of the work or pay for his share of the materials

the others can after ten days notice perform the work or make the payment

and receive a lien on the deliquent owner's share in the works. 297

648

37

In the construction of works a registered qualified engineer must be in

charge298 and the completed works must pass inspection of the state

engineer. 299 The owners of any works for storage, diversion, or

carriaqe of water can make application to store excess water, but as

trustee of the right they must deliver the excess to others when needed.

300

The most important and far reachinq aspect of this area of diversion

by water works is found in the right of eminent domain.

In 1900, the

Territorial Supreme Court of Ne\'1 t1exico recognized in arid regions the

construction of systems of reservoirs, canals, and ditches for domestic

.. '

use or use in i rri gating 1ands is a pub 1i c rurpose and the right of

eminent domain is a necessity for such purposes.3°1

The rationale

behind this condemnation of a land right-of-way for construction of

water works lies in the idea that beneficial use of water is a public use

so the water right

m~mer

should not be denied the access to apply the

water to a beneficial use.302 The statute is very broad in stating:

The United States, the State of Ne\'1 Mexico or any

person, firm, association, or corporation, may exercise

the right of eminent domain, to take and acquire land

right-of-way for the construction, maintenance, and

operation of reservoirs, canals, ditches, flumes, aqueducts, pipelines or other works for the storage or conveyance of water for beneficial uses, including the right

to enlarge existing structures, and to use the same in

common with the former owner; •••• 303

649

38

This includes every person having a water right, and does not distinguish

304

. d un der th e ac t or pre-ex1st1ng

. .

.

rig hts acqu1re

r1ghts.

Another statute allows the m•tner of any water works to deliver

water and supply appropriators by taking either above or below the part

of delivery, a quantity of water equivalent to that delivered, less a

proper deduction for evaporation and seepage which is to be determined by

the state engineer.305 Other water users cannot be injured by this

exchange.306

In interpreting the eminent domain statute307 and this

exchange statute, 308 the court decided the land right-of-way can be

condemned even by a junior appropriator, and the ditch company can

deliver the \'later to junior appropriators but there must be compensation

for both of these. 309

6. Relative Rights Among Appropriators

An appropriator with a water right which has an earlier priority

date than another appropriator is referred to as a senior appropriator.

The appropriator vii th the most recent priority date is known as the

junior appropriator.

Generally, the senior appropriator is entitled

to use of the water and the junior appropriator only receives \-/hat water

is remaining after the senior appropriator needs have been supplied. 310

The New ~1exico Constitution 311 and statutes 312 recoqnize this principle

by stating that

11

priority of appropriation shall give the better right."

The senior appropriator is limited to applying the water for a beneficial

use and once he has met his requirement he is not entitled to any

water in excess of this aMount, since use of the excess water belonos to

..

6f)0

(..

39

the junior appropriators. 313 The senior appropriator is entitled only

to his

require~ent

of beneficial use and once it is satisfied he no longer

has a right to the use of the water but must pernit the junior appro. t or t o use 1. t • 314 Th e sen1or

. appropr1a

. t or 1s

. not ent1t

. 1ed to waste

pr1a

315

water.

The common remedy of the senior appropriator is to bring an

action to enjoin the junior appropriator from using the water.316 Once

suit is brought, the burden of proof is on the senior appropriator to

show that his application of the water is to a beneficial use, then the

burden shifts to the junior appropriator to prove there is surplus water

that may be .. 'taken v.rithout injuring the senior appropriator's rights. 317 ,·

The statutes pertaining to change of point of diversion318 or

well location 319 seem to necessitate a showing that the change will not

ir:1pa i r any rights, \'lhether junior or senior to the app 1i cant's. A c1oser

look shows that the phrase "existing rights" is used in both statutes.

There is the possibility that this phrase might only be in reference to

the applicant's rights, which would make the statutes meaning read;

the applicant must prove that there is no impairment of a senior appropriator's rights.

_l!l Harley v. United States Borax and Chemical Corporation320,

the Court initiated the requirement that a senior appropriator

a der.tand for sufficient water to fill his needs.

~ust

make

The downstream senior

appropriator who used water to irrigate his crops claimed that the upstream junior appropriator failed to

allo~r

sufficient water to reach

his point of diversion. The Court held that the senior appropriator

has no right to have the water reach his diversion point if he does not

651

40

need it, and if he needs it and it is not reaching him, he must make his

/

32

needs known .} ·the prob 1em \A!i th this decision is that the Court does not

decide whether the demand should be made to the state engineer, the

water master, the junior appropriator, or a combination of them.

7. Loss of the Right

Abandonment, forfeiture, prescription (adverse possession), and

estoppel are four ways an appropriative right can be lost. To constitute

an abandonment the o\'mer must relinquish his right \'tith the intention

to abandon it. 322 Usually the abandonment is voluntary since it involves

intent, but in New Mexico after a long period of nonuse the burden

of proof shifts to the holder of the water right to show reasons for

nonuse, and an intent to abandon will be inferred in the absence of a

good excuse. 323 In State ex rel. Reynolds v. South Springs Co.,3 24

the period of nonuse was 26 years but the reason was because the spring

from which the appropriator diverted his water had dried up.

It is

evident that the court made its determination solely on the unreasonable

period of nonuse because clearly the excuse for nonuse was sufficient.

There is a statutory forfeiture provision in \'lhich unused \<Jater

(except for vtater in a storage reservoir) reverts to the pub 1i c and is

considered unappropriated water \'lhen the owner of the water right fails

to beneficially use all or any part of his right for a period of four

years. 325 At first glance this provision appears to have some teeth in

it, but upon further inspection numerous exceptions and restrictions

lessen its force.

Some of the exceptions are as follows:

652

(1) there is no

41

forfeiture if the nonuse is beyond the control of the m·mer in spite

of diligent efforts on his part; (2) the acreage is under a reserve or

conservation program provided by the Soil Bank Act; (3) the state engi\..

neer can extent the time upon proper showing of delay or he finds it is

within public interest; (4) municipalities are implementing a water

development plan; and (5) when nonuser is on active duty as a member

326

of the armed forces.

The most siqnificant restriction requires the

state engineer after the four years of nonuse to give ~:. rri tten notice of

the nonuser for a period of one year and if the v1ater is sti 11 not put to

beneficial tise then and only then will it revert to the public. 327 Thus:

the period for forfeiture is actually five years and only after notice

and declaration of nonuser given by the state engineer. The lack of