THE CONTINUING BATTLE WITH THE

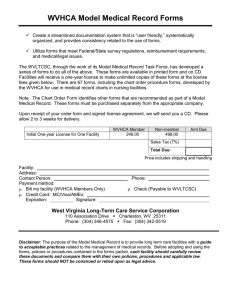

advertisement