EMPLOYEE BENEFITS LAW by Jayne Elizabeth Zanglein* 645 II.

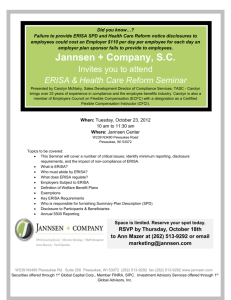

advertisement