T H E P R I V A T... A S U R V E Y O...

advertisement

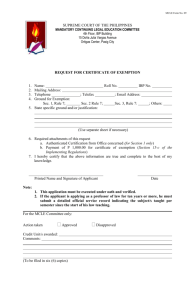

THE PRIVATE OFFERING A SURVEY OF C U R R E N T Sealy n•/» >-« EXEMPTION: DEVELOPMENTS Cavin THE PRIVATE OFFERING EXEMPTION: A SURVEY OF CURRENT DEVELOPMENTS Securities Regulation Professor Hal Bateman Sealy Cavin December 4, 1979 I, INTRODUCTION The heart of the Securities Act of 1933*" is section 5, which generally prohibits the "use of any means or instruments of transportation or communications in interstate commerce or of the mails o to sell (a) security," for such security. unless a registration statement is in effect Although section 5 is stated in broad terms, it can only be understood when read in conjunction with the other 3 sections of the Act. It is these other provisions which delineate the parameters of the section 5 prohibition. Section 4 of the Act:^ sets forth the transactions which are exempted from the registration requirements of section 5. Congress exempted these transactions from the rigors of section 5 because there was no practical need for registration or the public benefits 5 from such registration were too remote. The focus of this article will be on section 4(2) of the Act which exempts "transactions by an issuer not involving any public offering" from the registration requirements of section 5. The purpose of this article is to examine the significant current developments in the area of the private offering^ exemption. To assist the reader in bringing the historical background into perspective with the current developments, however, an analysis of the evolution of the private offering exemption will precede the section on current developments. 28 9 II. A. THE EVOLUTION OF THE PRIVATE OFFERING EXEMPTION The Private Offering Exemption Before Rule 146 Although section 4(2) clearly exempts transactions not involving a "public offering" from the registration requirements of section 5, the Act fails to describe the types of private sales which might qualify for the exemption. Thus, it appears that the availability of the private offering exemption is dependent, on the meaning of "public offering," which is nowhere defined in the Act. Furthermore, the legislative history is of little assistance in determining the scope of the private offering exemption. The House Report on the Act suggests that Congress was concerned that there be "full and fair disclosure" of the facts describing the character of new offerings of securities. Accordingly, the private offering exemption was intended to be available only where the 9 need for full disclosure did not exist. In this context, the House Report provides that the registration requirements of section 5 may only be avoided "where there is no practical need for its application or where the public benefits are too r e m o t e . O u t side these general remarks, the legislative history is of little assistance in determining the range of the private offering exemption. Thus, with Little guidance from Congress, the SEC and the courts set out to define the private offering exemption. In 1935, the SEC promulgated"^:he principal factors to be considered in determining the availability of the private offering exemption. Those factors are: "(1) The number of offerees and their relation- ship to each other and to the issuer; (2) The number of units 12 offered; (3) The size of the offering; and (4) The manner of offering." Three years after the 1935 SEC release, in SEC v, Sunbeam 13 Goldmines Co., ' the Ninth Circuit rejected the issuer's contention that the phrase "public offering" meant an offering to everyone. The court, after noting that the word "public" was inherently ambigious, stated that to define "public offering" as an unrestricted 14 offering to the world at large is inadequate for oractical purposes. "To determine the distinction between ptiblic and private in any particular context, it is essential to examine the circumstances under which the distinction is sought to be established and to 15 consider the purposes sought to be achieved by such distinction." Thus, the court determined that the question of whether the private offering exemption would be allowed would depend on an analysis of all the facts and circumstances surrounding the offering. It was not until 1953, however, that the Supreme Court attempted to delimit the boundaries of the private offering ]exemption. 6 In SEC v. Ralston Purina Co., the Supreme Court was confronted with the question o.f whether an offering of unregistered stocks to "key employees" qualified as a private offering for the purposes of 17 the section 4(2) transactional exemption. The court, in holding that the offering did not qualify as a private offering, determined that "the applicability of section [4(2)1 should turn on whether the particular- class of persons affected needs the protection of the Act. An offering to those who are shown to be able to fend 18 for themselves is a transaction not .involving any public offering." Furthermore, noted the court, whether an. offeree can. fend for himself depends on whether he has "access" to the same information which a registration statement would disclose. 19 ICr. 4 In Ralston Purina, the SEC e once tided that the offering x-ras pixblic merely because of the large t7umber of offerees. The court rejected the SEC's contention and stated that a numerical limitation placed on the private offering exemption is unwarranted as a matter of statutory interpretation. 20 Nothing prevents the SEC, however, from using a numerical test to determine which 2] offerings to investigate. Although it would be rare that the private offering exemption would apply when a large number of offerees were involved, 22 the number of offerees alone is not 23 determinative of the availability of the exemption. Thus, in defining the word public "(n)o particular numbers are prescribed. Anything from two to infinity may serve: perhaps even one, if he is intended to be the first of a series of subscribers, but makes fxirther proceedings needless by himself subscribing the whole."24 Thus, in Ralston Purine), the Supreme Court suggested two criteria for determining what constitutes a private offering: First, do the offerees need the protection provided by registration; and second, do the offerees have access to the 25 type of information which a registration statement would disclose. It is these, less than precise, criteria which later caused problems in the Fifth Circuit, brought about a wave of criticism by the commentators, and ultimately led to the promulgation of rule 146 by the SEC. Following Ralston Purina, an issuer who hoped to qualify for the private offering exemption was well advised to comply with the two requirements announced by the Supreme Court. rtsi U'l It was thought chat the "need" requisite could he satisfied by only 26 offering the securities to a "sophisticated" investor. As to the "access" requirement, many believed that the offeree must be provided with information which a registration statement would disclose, or in the alternative have access to such information. It was in the early 1970's when the Fifth Circuit had occasion to interpret the "access" requirement. These interpretations, although largely in the form of dicta, were met with a great deal of criticism from the securities bar, and led to the eventual adoption of rule 1.46. In 2 7 Hill York Corp. v. American International Franchises, Inc. , " the Fifth Circuit, was faced with the question of whether the offeree's high degree of sophistication, in and of itself, would support the issuer's claim that, the offering was private. In Hill York, "the. offering was made only to sophisticated busines men and lawyers and not the average man in the street." 28 The court noted, however, that the level of sophistication alone would 29 not qualify the offering for the exemption. "Obviously if the (offerees) did not possess the information requisite for a registration statement, they could not bring their sophisticated knowledge of business affairs to bear in deciding whether or not to invest . . . ."30 Thus, ostensibly, Hill York requires the issuer to actually provide information similar to that found in a registration statement, 31 unless the offeree has a "privileged relation 32 ship' with the issuer. It was the Fifth Circuit's decision in SEC v. Continental Tobacco C o , h o w e v e r , that had the securities bar claiming that the private offering exemption was a dead letter. QO This case sent the SEC fro the drafting board, resulting in the proposal of rule 146 in the fall of 1972 and the ultimate adoption of that rule 34 in 1974." Because rule 146 operates as a nonexclusive provision, Continental Tobacco will continue to be of some import, particularly in the Fifth Circuit, in determining whether an offering35qualifies for the private offering exemption outside of rule 146. In Continental Tobacco, the issuer, following Chapter XI bankruptcy proceedings, was involved in a refinancing program. The program included meetings with prospective investors who were not directly associated with the issuer. At these meetings, the offerees were shown movies and given prospectuses of the company. After an investigation of these offerings, the SEC petitioned the district court for an iniunetion against the issuer for violations of the registration requirements of section 5. The district court denied the SEC's request for an injunction, and the SEC appealed. Overly eager to have the Fifth Circuit reverse the district court, the SEC contended on appeal that only corporate "insiders" could qualify as private placement offerees. 37 According to the SEC's appellate brief: Before the statutory protections may be safely eliminated in any case, the issuer must affirmatively demonstrate by explicit., exact evidence that each person to whom unregistered securities were offered was able to fend for himself -- in other words, that each, offeree had a relationship to the company tantamount to that of an insider in terms of his ability to know, to understand and to verify for himself all of the relevant ryrti tlO 7 facts about the company and its securities. This type of offeree through his own knowledge, sophistication and unfettered access to the citadels of corporate power and decision-making can protect himself; he does not 38 require the protection of the Act , . . . Thus, it was the SEC's position that the mere disclosure of the same information that a registration statement would provide is, in and of itself, insufficient to meet the "access" requirement. of Ralston Purina. Stating that it must follow the test announced in Hill York, the court noted that in order to qualify for the private offering exemption the offerees must have a privileged relationship with the 39 issuer. Furthermore, stated the court, relying on the SFC's brief, "(e)ven if it were assumed that Continental's prospectus provided those offerees, to whom it was disseminated, with all the information that registration would disclose, this would not suffice to establish the requisite relationship of those offerees to the .,40 company.' Following Hill York and Continental, at least in the Fifth Circuit, the private offering exemption was seemingly lost unless: 1. The offer was made to a limited number of offerees 2. who must be sophisticated purchasers having a relation to each other and to the issuer; 3. with access to all the information a registration would disclose; and 4. with an actual opportunity to inspect the company's records or otherwise verify for themselves the statements made to them as inducements for the purchase.^ 8 It was these developments that prompted the SEC to propose and ultimately adopt the "objective criteria" of rule 146, B. Rule 146 Rule 1464*2" was adopted by the SEC to provide issuers with more objective standards for determining whether an offering qualifies as a private offering exemption within the meaning of section 4(2) 4°> of the Act. ~ This rule, however, is not the exclusive means by which an issuer may qualify for the private offering exemption, and if the issuer complies with judicial and administrative 44 interpretations of section 4(2) the exemption will be available. Thus, although rule 1.46 is not free of subjective criteria, the commission hoped that the standards set out in rule 146 would45cure some of the uncertainties that existed prior to its adoption. Before proceeding with an analysis of rule 146, its structure should be defined. As with the other rules in this series, rule 146 consists of preliminary notes followed by definitions. The preliminary notes disclose the SEC's policies and the purposes behind the rule. The definitions, which follow the preliminary notes, precede the conditions which must be complied with in order to qualify for the rule 146 exemption. With this structure in mind, to assist the reader in making the transition from the prerule 146 offerings to the post-rule 146 offerings, it is appropriate to summarize the rule and briefly discuss some of its more salient points. In summary form, the requirements of rule 146 are as follows: (1) The issuer or any person acting on its behalf shall neither offer nor sell the securities by means of any form of general solicitation or advertising, including advertisements, seminars or meetings, or any letter or other written communications, except in cases where all those invited to and attending meetings and all those receiving written communications satisfy the conditions of paragraph (2) below, (2) The issuer shall have reasonable grounds to believe: (a) immediately prior to making any offer, either: (i) that the offeree has "such knowledge and experience in financial and business matters that he is capable of evaluating the merits and risks of the prospective investment," or (ii) that the offeree .is a person "who is able to bear the economic risk of the investment"; and (b) immediately prior to making any sale, after making reasonable inquiry, either: (i) that the offeree has such knowledge and experience, or (ii) that the offeree and his offeree representative(s) together have such knowledge and experience and that the offeree is able to bear the economic risk of the investment. (3) Each offeree shall either,(a) have access to the same kind of information that is required by Schedule A of the 1933 Act (including financial statements, description of business, etc.); or (b) have furnished to him or his offeree representatives the same kind of information that is required by such Schedule A. (4) Each offeree or his representative shall have the opportunity to obtain any additional 10 information necessary to verify the accuracy of any such information and to ask questions and receive answers from the issuer. (5) Each offeree shall be informed in writing by the issuer that, he must continue to bear the economic risk of the investment for an indefinite time and that the securities cannot be sold unless they are subsequently registered or an exemption is available. (6) There shall be no more than thirty-five persons who purchase securities of the issuer of the same or similar class in any offering pursuant to the rule. (7) The issuer shall exercise reasonable care to assure that the persons purchasing the securities from the issuer are not underwriters, including: (a) making reasonable inquiry to determine if the purchaser is purchasing for his own account; (b) placing a legend on the certificate stating that the securities have not been registered and setting forth or referring to the restrictions on transferability; (c) placing stop-transfer instructions against the shares on the books of the issuer and the transfer agent; and (d) obtaining from the purchaser a written agreement that the securities will not be sold without registration or under an exemption. 46 The operative part of rule 146 is found in paragraph (b) of that rule. Paragraph (b) provides that if all of the conditions of rule 146 are met, then the offering "shall be deemed to be (a) transaction not involving any public offering within the meaning 11 of section 4(2) of the Act." 47 It is around this operative part which the rest of the rule revolves. Paragraphs (d) and (e) comprise the most important part of the rule. These paragraphs attempt to define the two criteria announced by the Supreme Court in Ralston Purina.^ Paragraph (d) deals with the offeree's ability to fend for himself, and paragraph (e) deals with the problem of access to information. Pursuant to rule 146, the issuer or someone acting in behalf of the issuer must have reasonable grounds to believe that the offeree is qualified,^ To be qualified, the offeree must either have such knowledge and experience in business matters that he can evaluate the risk of investment,^^ or be wealthy enough to bear the risk of investment."^ If the offeree falls in the latter category he must possess the knowledge and experience in business matters to enable him to evaluate the risk of investment, 52 or together with his repre53 sentative possess such "sophistication." Thus, with the advent of rule 146, the issuer can now rely on the sophistication of the offeree's representative, if the offeree can bear the economic risk. This concept of the "offeree's representative" represents a break from the past, which provides the issuer with a relatively safe way 54 of satisfying the sophisticated offeree requirements. 55 The "access to information" provision has clarified the access requirement, and laid to rest some of the eccentric notions promulgated by the Fifth Circuit. Thus, the notion that an offeree must have a "privileged relationship" giving him access to certain information is displaced by rule 146, which instead requires that the offeree have either access or be furnished with the requisite information. vQ 12 Unless the offeree has access to the same kind of information that is required by Schedule A of the Act, the offeree or his representative must be furnished certain information. As a note to rule 146(e) points out, "access" can only exist because of an employment, 56 family, or financial relationship. Without one of these relation- ships, the issuer must actually provide the information required. The character of the information which must be furnished pursuant to paragraph (e)(1)(ii) depends on whether the issuer is subject to ther.oreporting requirements of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. For companies reporting under the 1934 Act, the information requirement shall be satisfied by supplying the information contained in the annual report required to be filed under the 1934 Act or a registration statement on Form S-l under the 1.933 Act or under Form 10 under the 1934 Act, whichever of the three is most recently filed. 59 In addition, the issuer must provide any definitive proxy statement required to be filed under sections 13(1) or 15(d) of the fin 1934 Act. Finally, the issuer must supply "(a) brief description of the securities being offered, the use of any proceeds from the offering, and any material changes in the issuer's affairs which 61 are not disclosed in the documents furnished." Thus, what was once a subjective requirement is converted into an objective condition, which "should be an important factor causing 1934 Act companies more (3 2 readily to issue stock pursuant to section 4(2) and rule 146 . . . ." For companies that do not report under the 1934 Act, rule 146 requires them to provide information that would be found in a registration statement filed under the 1933 Act on the form which the issuer would be entitled to use. f> The issuer is not required, 13 however, to provide audited financial statements required by such form if they cannot be obtained without unreasonable effort or expense. £/ Furthermore, the issuer may omit details if the omitted 65 information is not material. But for these exceptions, the issuer is essentially required to go through a full fledged registration process. Thus, "(s)uch companies may consider rule 146 nearly as burdensome as a full registration but with the same, degree of . • ,,66 certainty. Although the Supreme Court in Ralston Purina rejected a numerical test for determining whether the private offering exemption was available, it noted that for the purpose of investigation the SEC could &7 adopt a numerical test. Since rule 146 is nonexclusive, the numer- ical limitation imposed by paragraph (g) is seemingly appropriate, and the issuer will not be deprived of the private offering exemption if it otherwise existed under the case law and administrative decisions interpreting section 4(2). Paragraph (g) sets forth the basic proposition saying that in order to qualify for the private offering exemption under rule 146, the issuer shall have reasonable grounds to believe, and after reasonable inquiry, shall believe, that there are no more C Q than thirty-five purchases in any offering pursuant to this rule. 1 As the prelimi69 nary notes indicate, ' in determining whether an offer or sale is part of. a larger offering, the traditional concepts of integration must be dealt with. The traditional integration concept, however, is tempered by the "safe harbor" provision of paragraph (b) which provides in part that: For the purposes of (rule 146) only, an offering shall be deemed not to include offers, offers to ft w 14 sell, offers for sale or sales of securities of the issuer pursuant to the exemptions provided by section 3 or section 4(2) of the Act or oursuant to a registration statement filed under the Act, that take place prior to the six month period immediately preceding or after the six month period immediately following any offers, offers for sale, or sales pursuant to this 70 rule . Thus, in determining the number of purchasers involved in a given offering, both the traditional integration concepts and the "safe harbor" provision of paragraph (b) must be taken into account. Paragraph (g)(2) provides that certain purchasers shall be excluded from the computation of the number of purchasers for the purposes of paragraph (g)(1). Three of the exclusions are based on some relationship betxveen two purchasers, 71 and the other exclu72 sion depends on the aggregate amount of the purchase. Addition- ally, unless such entity was organized for the specific purpose of acquiring the securities, any corporation, partnership, association, joint stock company, trust7 3or unincorporated organization shall be counted as one purchaser. " Although the numerical limitation is couched in terms of "purchasers" rather than "offerees," the issuer has the burden of establishing, with respect to each offeree, that all the conditions of the rule have been satisfied.^4 Rule 146 provides the issuer who is seeking the private offering exemption with some objective standards on which to base his actions. This improvement is far from a panacea; therefore, some subjective portions of the rule will require attention. Furthermore, the rule 15 132 is expressly nonexclusive, meaning that the securities practitioner will want to stay abreast of developments under section 4(2) which are not within the confines of rule 146. Some of the problematic areas of rule 146, along with recent developments under the private offering exemption outside of rule 146, are covered in the current developments portion of this article. III. A. COMPENDIUM OF RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN THE PRIVATE OFFERING EXEMPTION Developments Outside of Rule 146 An offering that is made in accordance with all of the conditions of rule 146 shall be deemed a private offering for the purposes of section 4(2) transactional exemption.^ Although rule 146 provides a "safe harbor" for those issuers who comply with its conditions, it is not the exclusive means by which an issuer may qualify for the private offering exemption. As stated in the preliminary notes to rule 146, "(t)ransactions by an issuer which do not satisfy all of the conditions of this rule shall not raise any presumption that the exemption provided by section 4(2) of the Act is not available for such transactions."^ Accordingly, the issuer can rely on the section 4(2) exemption "by complying with administrative and judicial interpretations in effect at the time of the transaction."^ The extent of the operation of the private offering exemption outside of rule 146, however, is not clear. It is clear that the SEC has remained adamant in its position that rule 146 is merely a nonexclusive "safe harbor," and not the sole means of achieving the private offering exemption. This position was recently reiterated in Release No. 5913. 79 I n Release No. 5913, the SEC responded 42 16 to the commentator's®® criticism of rule 146 and two recent Fifth circuit decisions which the commentator's believe demonstrate a propensity to replace the broad statutory exemption with the narrower 81 criteria of rule 146, 8? In Woolf v. S. D. Cohn & Co . , the Fifth Circuit referred to rule 146 as "a useful frame of reference to an appellate court o o in assessing the validity of section 4(2) exemptions . . . ." Further- more, noted the court, although rule 146 is nonexclusive, "(i)t is probable . . . that practitioners will be unwilling to stray from the safe harbor the rule apparently affords . . . . Although the court speaks of rule 146 as "a useful frame of reference," its opinion is well supported by the case 85 law discussed, and thus the reference is in a persuasive context. The admonition to practi- tioners is merely a prudent observation which practitioners should keep in mind when developing a private offering.^ 87 Two years later, in Doran v. Petroleum Management Corp., the Fifth Circuit again made reference to rule 146, but again as in Woolf it was merely used as persuasive authority. The court was impressed with rule 146's disjunctive requirement that the offeree must either have access to or actually be furnished with certain information. 88 As the court noted, however, this disjunctive re89 quirernent had already been implicitly accepted in the Fifth Circuit. The court expressly noted again, as in Woolf, that rule 146 was nonexclusive. Thus, while the court found rule 146 useful on the access issue, its opinion in Doran was primarily based on case law. Although these two cases were the focal point of much criticism, it is the SEC's position that this criticism is unwarranted. 90 In iiJ both cases the court expressly noted that rule 1&6 was nonexclusive, and in both cases- rule 146 was referred to as indirect authority only. Thus, while some critics might contend that the private offering exemption outside of rule 146 is a dead letter, the SEC has reiterated its position that rule 146 is merely a nonexclusive safe, harbor. These assertions by the SEC must, however, be tempered with the practicalities. Though rule 146 is nonexclusive, the SEC has ex- pressed a reluctance to consider "no-action" requests relating to 91 the private offering exemption outside of rule 146. In close cases, "no-action" letters are very important to the prudent practioner, and their unavailability may deter reliance on the exemption outside of rule 146. Thus, for practical purposes rule 146 may be the exclusive means by which the prudent practitioner will attempt to qualify for the private offering exemption. The possi- bility for operation outside the rule, however, still exists. 1. Resale of encumbered securities acquired initially in a private offering. Paragraph (c.) of rule 146 places limitations on the manner in which a private offering under rule 146 can be achieved. graph (c) provides in part: Neither the issuer nor any person acting on its behalf shall offer, offer to sell, offer for sale, or sell the securities by means of any form of general solicitation or general advertising, including but not limited to, the following: (1) Any advertisement, article notice or other communication published in. any newspaper, magazine or similar medium or broadcast over television or radio . . . . 92 Para- From ibis provision, it is clear that an offering pursuant to newspaper advertisement, notifying the public of a public auction of securities, does not qualify for the private offering exemption 93 under rule 146. ' 94 In United Properties of America, the SEC staff was faced with the question of whether it was appropriate to issue a "noaction" letter in response to a proposed sale of stock at a public auction. The stock of United Properties of America (UPA), a California corporation, was owned by two individuals. UPA owned a judgment against Ludlow Flower, a 14 percent stockholder of UPA. The judgment was based on a debt which was secured by Flower's stock in UPA. UPA proposes to offer the pledged securities for 95 sale at a public auction pursuant to UCC section 9-504, registration. without It is UPA's position that section 9-504 requires a public sale if the secured party is to be permitted to purchase the shares. UPA intends to conduct the sale in a commercially reasonable fashion, which includes, among other things, a publication of notice of the sale in a newspaper of general circulation. As is often the case, it appears that the secured party, UPA, will be the purchaser of the shares. UPA indicated a willingness, if necessary to qualify for the section 4(2) exemption, to sell the shares only as a block, require an investment letter from the purchaser, and legend the shares with a standard notice that the shares may not be sold or otherwise transferred without compliance with the 33 Act. Based on the information submitted, the Division indicated that it would not recommend any enforcement action to the Commission, if the transaction was effected as proposed. 19 This response by a Division of the SEC lends credibility to the SEC's assertion that rule 146 is nonexclusive. It indicates that the SEC is willing to allow a private offering exemption, even though it does not comply with rule 146, where there is no practical need for registration. Furthermore, it shows that under compelling circumstances the SEC will issue "no-action" letters relating to the private offering exemption outside of rule 146. 2. Operating outside of rule 146: What can the practioner expect ? Prior to the adoption of rule 146 in 1974, the availability of the private offering exemption was dependent on compliance with 96 the criteria promulgated by the Supreme Court in Ralston Purina. 97 These criteria, as interpreted by the Fifth Circuit, adoption of rule 146. led to the The SEC adopted rule 146 so that issuers seeking the private offering exemption could plan their affairs with some predictability. Thus, because the case law was so muddled, the SEC deemed it necessary to promulgate objective standards. An issuer who hopes to qualify for the private offering exemption outside of rule 146 must be prepared to grapple with the decisions interpreting the pre-rule 146 exemption. Although the section 4(2) exemption as it exists outside of rule 146 leaves much to be desired, it may in many instances be invaluable. This value emanates from the all or nothing pro- vision of the rule. The operational part of rule 146 is found in paragraph (b) which requires the issuer to comply with all of the conditions of rule 146 if the offering is to qualify for the private iiJThis offering exemption, under the rule. requirement is uncompromising, 20 and even an immaterial failure to comply with rule 146 will cause it not to apply. Thus, it is not hard to imagine a court sympa- thizing with an issuer who has become a victim to an immaterial flaw in an otherwise valid 146 offering. Naturally,this sympathy might manifest itself in the court allowing the exemption to stand as a private offering exemption outside of rule 146. In conclusion, the importance of the private offering exemption, as it exists outside of rule 146, is diminishing. Under some cir- cumstances, however, this exemption will continue to be significant. Prudence will dictate that, when possible, the practitioner will take advantage of the "safe harbor" provided by rule 146. B. Recent Developments Under Rule 146 In 1974, the SEC adopted rule 146 to alleviate the confusion created by the courts and the SEC in the area of the private offering exemption. It was hoped that rule 146 would provide practitioners with "objective standards" for planning private offerings. These "objective standards," however, are not without subjective soft spots. It is these subjective soft spots, along with certain struc- tural changes, that provide the content for the remainder of this article. 1. Structural changes In 1978, the SEC amended rule 146 to require the filing of a report with the SEC upon the first sale of securities under rule 146. 98 This amendment is found in paragraph (i) of the rule, and requires all issuers raising more than $50,000 during any twelve99 month period to file the report on Form 146. The SEC believed this reporting device to be necessary for two reasons: (1) the 21 Commission needed empirical data on the use of rule 146 as a "safe harbor," and (2) a need to nip fraudulent offerings in their . . . . „ 100 incipient stages. With the adoption of this provision, the SEC has thrown one more obstacle in front of the small issuer. Apparently content to shuffle paper, the SEC has required that the issuer file another 101 form in order to meet all of the conditions of rule 146. Further- more, oaragraph (i) requires issuers who are already subject to the periodic reporting requirements of the 102 34 Act to file the forms. As determined earlier by the Commission, filing of such Forms unnecessarily increases the difficulty of complying with the rule. As compliance with rule 146 becomes more difficult, the issuer must ask if such efforts are warranted when contrasted with the predictability that registration affords. Thus, while reporting the offering on Form 146 is seemingly innocuous, it is but one of the elements which might dissuade a small issuer from raising capital under rule 146. More recently, however, the SEC has made the rule 146 exemption more appealing to the small issuer 103 by amending the disclosure requirements of paragraph (e). Prior to this addition, issuers who were not subject to the reporting requirements of the 34 Act were required, with certain exceptions, to provide offerees with information that would be required to be included in a registration statement. Now, with the adoption of this provision, if an offering is for less than $1,500,000 the issuer can satisfy the disclosure requirements of paragraph (e) by supplying the offerees with the information required by Sechedule I of Regulation iiJ 22 Ostensibly, this amendment was the SEC1s answer to the general wave of criticism which followed the adoption of rule 146.^"' Manv commentators complained that the burden of compliance with rule 146 was nearly as tough as compliance with the registration requirements. ^ ^ Moreover, they note, because registration provides the issuer with a higher degree of certainty, 108 protection, and affords more many issuers will forego the rule 146 offering in favor of registration. Accordingly, in response to these criticisms, the SEC has opted to ease the disclosure requirements where the offering does not exceed $1,500,000. Thus, while the SEC eased the burden of compliance by easing the disclosure requirements, it made compliance more onerous by requiring issuers to file Form 146 upon the first sale of securities. How issuers will react to these changes remains to be seen. 2. Interpretations of rule 146 Rule 146 was adopted by the SEC to provide issuers with more objective standards for determining whether the private offering exemption is available. These objective standards, however, are not without subjective soft spots. These soft spots, which have been subject to SEC interpretation, are discussed in the remainder of this article. a. Offeree representative The "offeree representative" concept represents an innovation in the private offering exemption. This concept allows the issuer to rely on the sophistication of the offeree's representative, if the offeree can bear the economic risk involved. Thus, with the advent of rule 146, the offeree may have little or no financial sophistication, if he can bear the economic risk and if he is 23 represented by an "offeree representative." Paragraph (a)(1) defines the terra "offeree representative" as any person whom the issuer, after making reasonable inquiry, has reasonable grounds to believe satisfies all of the following conditions: (1) Is not an affiliate, director, officer or other employee of the issuer, or beneficial owner of 10 percent or more of the equity interest in the issuer, except where the offeree bears a certain relationship to such person; (2) has such knowledge and experience in financial and business matters that he is capable of evaluating the prospective investment; (3) is acknowledged by the offeree, in writing, to be his offeree representative in connection with evaluating the prospective investment; and (4) disclosed to the offeree, in writing, and material relationship between such person and the issuer, and any compensation received or to be received as a result of the relationship. Although this definition leaves many question unanswered, it is beyond the scope of this article to discuss all of these ambiguities. 111 Clearly, the definition of "offeree representative" provides that in order for a person to qualify he must not be an employee 112 of the issuer. It is equally clear, however, that the possi- bility of such representative being compensated by the issuer is 113 not precluded. Thus, from these observations it must be con- cluded that an employer-employee relationship, for the purpose of defining an "offeree representative," should not be founded on iiJ the payment of compensation alone. These provisions obviously 24 leave many questions unanswered with respect to who is deemed to be an employee of.the issuer. In Pension and Investment Associates of America, Inc. (PIAA) the SEC was confronted with the question of whether registered representatives of a broker-dealer, who receive a commission upon sales of securities, may act as an offeree representative under rule 146 for offerings of limited partnership interest in which the broker is a general p a r t n e r . T h e facts, as described in the letter of inquiry, involved a plan in which PIAA was considering becoming a co-general partner in connection with a proposed private sale of investment units pursuant to rule 146. PIAA, as co-general partner, would expect its registered representatives to sell units in the proposed offering. It was PIAA's contention that these registered representatives were not "employees of the issuer," and thus qualified as "offeree representatives." PIAA maintained that because these represen- tatives only received commission upon the sale of securities, and because they are obligated to sell their customers only suitable securities, they are merely independent contractors and not 116 employees. In the alternative, PIAA argued that assuming that the registered representatives are employees, they are employees of an affiliate and the rule appears to prohibit only employees of the issuer. 117 The SEC was not persuaded by these arguments, ruling that the registered representatives of PIAA could not serve 118 as offeree representatives. Although the staff reply is of little assistance in determining the extent of the ruling, it would appear that this ruling should 25 be strictly limited to tbe facts as provided. More precisely, were it not for the fact that PIAA had previously had "employment" relationships with the registered representatives the outcome might have been different. The fact that PIAA is a registered broker is also seemingly significant. In fact, the possibility that the registered representatives might put PIAA first and their customers second is apparently an important consideration. Thus, this interpretation should not be construed to extend beyond the specific factual situation involved. In particular, it should not be construed as a blanket prohibition against the payment of commissions by the issuer to the offeree representative. Following this ruling, the SEC proposed to amend rule 146 so that a person receiving compensation directly or indirectly from an issuer could not qualify as an offeree representative under rule 146. 119 Responding to the adverse views of the commentators, 120 121 the SEC withdrew the proposal within the year. The commentators opposed the proposal on two grounds. First, the effect of such proposal would be counter-productive in that it would do little to protect investors and further deter issuer reliance on the rule. 122 Second, the offeree representative owes significant loyalty to his customer and that any potential conflict 123 of interest is balanced by full disclosure. After all, noted the commentators, the securities act is based upon disclosure and such disclosure will adequately reveal any conflicts of interests. Agreeing with the commentators that the proposal should not be adopted, the SEC withdrew it. By withdrawing the proposal, the SEC merely considered the comments rather than concurring with them. Thus, from the SEC1s 26 acticms, it can be deduced that the payment of compensation by the issuer to the offeree representative, without more, will not preclude the issuer from qualifying for the rule 146 exemption. Clearly, this standard is of little assistance to the conscientious issuer. Arguably, the SEC agreed with the commentators' assessment that disclosure would rectify the conflict of interests problem. Even if one assumes that the SEC was somewhat persuaded by this position, however, it is doubtful that the SEC is willing to view disclosure as the "panacea." That is to say that while in some situations disclosure would prove adequate, in others it would clearly not 124 be adequate. Thus, in a situation such as the PIAA "case," where the issuer had a previous "employment" relationship with the proposed offeree representatives and the issuer was a broker, it is questionable whether mere disclosure will provide the offerees with sufficient protection. Accordingly, whether the issuer may provide compensation for the offeree representative will depend largely on the circumstances surrounding their relationship. b, Limitation on the number of purchasers Paragraph (g) provides that the issuer shall have reasonable grounds to believe, and shall believe, that there are no more 125than thirty-five purchasers in an offering pursuant to rule 146. To determine the number of purchasers, however, paragraph (g)(2)(i) must be consulted. Under the provisions of paragraph (g)(2) (i) certain purchases should be excluded from the computation. Furthermore, paragraph (g)(2)(i) provides that any corporation, partnership, association, joint stock company, trust or unincorporated organization shall be treated as one purchaser, unless such entity was 27 iiJ organized for the specific purpose of acquiring the securities offered.126 One provision which has been the central subject in several "no-action letters" is paragraph (g)(2)(i)(d). It orovides that any person who agrees to purchase at least $150,000 worth of securities in cash shall be excluded from the computation of t%e number 1? 7 of purchasers. " This exclusion was apparently included so that an unlimited number of "major purchasers" (generally institutional investors) could participate in a rule 146 offering so long as they purchased the requisite amount of securities. 128 129 In Robert S. Sinn Securities, Inc., the question presented by the inquirer was whether a person who gives a non-recourse promissory note as part of a more than $150,000 purchase price is on® who may be excluded in computing the number of purchasers pursuant 1 '•i 0 to rule 146. In this case, the "inquirer" (Sinn) proposes to become the general partner of a limited partnership. The limited partnership interest would be sold in a non-public offering, with the proceeds being used to purchase certain mineral interests. Some of these limited partnership interests would be valued at more than $150,000, and the purchasers would pay half the purchase price in cash and upon receipt of their certificates of interest would give non-recourse promissory notes for the balance. The security for these notes would be the investors proportional investment in the partnership, and there would be no recourse against the investor himself. The SEC staff ruled that such purchasers should be included in computing total number of purchasers accordingly, that 131 the paragraph the (g)(2)(i)(d) exclusion was not and, available. 28 Approximately one year later, in Marion Corporation, 132 the SEC was confronted with a similar factual situation. In this matter, the Marion Corporation was proposing the formation of a limited partnership in which the Marion Corporation would be the general partner. It was contemplated that certain investors would purchase interests valued in excess of $150,000. Although these purchasers might have paid the entire amount in cash, the company proposed an alternative which would allow the purchaser to pay twenty percent of the purchase price in cash with a letter of credit equal to eighty percent of his commitment. The letter of credit would be issued by a bank, naming the investor as the accountee and the partnership as payee. Presumably, each investor would be personally responsible to the issuing bank, and the partnership interest would provide additional, security. The partnership would use the letters of credit to secure funds from the issuing bank and these funds would be used to finance its drilling activities. As in the Sinn matter, the SEC was of the opinion that where eighty percent of the investment is represented by a letter of credit, such purchaser does not qualify for the paragraph (g)(2)(i)(d) exclusion. 133 "i Q / Following this, in PLM Inc., the "issuer" finally found a credit arrangement which was acceptable to SEC. PLM, the "issuer," anticipated that several purchasers would want to borrow up to eighty percent of the purchase price (all purchases x^ould be of $150,000 or more). The loans would be secured from a bank, with each loan being a personal obligation of the borrower. The bank would have full recourse against, the borrower's personal assets, and also retain a security interest in the investment. 42 In any 29 iiJ event, the prospective purchaser would be required to make full payment to PLM either by cash or check. Thus, before any title is taken, the entire purchase price must be paid. This arrangement, ruled the SEC, would qualify for the paragraph (g)(2)(i)(d) purchaser 135 exclusion. Can this ruling be reconciled with the rulings in Sinn and Marion? The PLM decision is clearly distinguisable from the Sinn ruling. First, in Sinn the proposed purchasers were not making a full cash payment to the issuer, but rather it was proposed that these investors would pay half in cash and the other half in promissory notes. note was to be drawn in favor of the issuer, Sinn. The In PLM, however, the notes were executed in favor of a bank in return for a loan. Thus, PLM received either cash or a check for the full purchase price and no notes were exchanged in the actual purchase. Second, in Sinn the notes were non-recourse, meaning that the investor had no personal liability for half of the purchase price. The converse was true in PLM, however, as the bank had full recourse against the drawer. The difference between Marion and PLM, however, is more subtle. In Marion, the investor would tender twenty percent in cash and eighty percent by a letter of credit. The corporation in turn would use the letters of credit to secure loans. Thus, as in Sinn, the issuer was only receiving part of the purchase price in cash or check while the remainder was in the form of a less liquid substitute. This is to be contrasted with PLM where the "issuer" actually received the entire purchase price in cash or check. In conclusion, to insure in a part credit transaction that a purchaser will be excluded from the number of purchaser computation 30 pursuant to paragaraph (g) (2) (i) (d), the issuer must: (1) receive- full cash payment-before delivering title; and (2) be sure that the 136 lender has full recourse against the purchaser. ~ Paragraph (g)(2) (ii) provides that (t)bere shall be counted as one purchaser any corporation, partnership, association, joint stock company, trust or unincorporated organization, except that if such entity was organized for the specific purpose of acquiring the securities offered, each beneficial owner of equity interest or equity securities in such entity 137 shall count as a separate purchaser. " This provision was included to prevent groups of individuals, who wished to participate in a private offering, from joining themselves into entities in order that they might circumvent the numerical limitations imposed by the rule. This subterfuge of organising an entity solely for the purpose of keeping down the number of offeree-purchasers had originated prior to the adoption of rule 146. 138 Although such devices are typically treated as a fraudx.ilent practice, the SEC has deemed it of sufficient import to include i 39 a provision within the rule itself. An example of the fradulent use of such entities is found in United States v. Custer Channel 140 Wing Corp. In Custer, a million and a half shares of securities were sold in what the issuer termed a private offering. were sold to twenty-two named purchasers. The shares Three of the twenty-two named purchasers, however, were "associates," which were comprised of 136 individual investors. These "associates," noted the Fourth Circuit, were merely conduits for a public offering. 1 / T Thus, with aim to undermine the Custer type of subterfuge, paragraph (g)(2)(ii.) was included in the rule. 31 It was against this background that the SEC was confronted with the matter of Henry Crown Partnership. In Henry Crown, the "inquirer" anticipated the formation of a partnership. As planned, the partnership would invest primarily in oil and gas ventures which were privately offered. Although the partnership would be organized to purchase such interests, there were at the time of inquiry no specific investments planned. Noting that the exception in para- graph (g)(2)(ii) was aimed at entities formed for the specific I/O purpose of acquiring any particular securities, the SEC ruled that the partnership in question should be considered a single purchaser. Thus, an entity formed for the general purpose of acquiring securities in suitable private offerings, as opposed to an entity formed for the preconceived purpose of purchasing any particular securities, will be considered a single purchaser.^^ IV. CONCLUSION 146 The adoption of rule 146 in 1974 private offering exemption a new look. has given the section 4(2) Now, with the advent of rule 146, there are essentially two section 4(2) private offering exemptions. ^ ^ First, there is the traditional private offering exemption. The requisites for this exemption must be gleaned from the judicial and administrative interpretations of section 4(2). Second, there is the private offering exemption pursuant to rule 146. An issuer may qualify for this exemption by complying with all of the conditions set forth in the rule. exemptions: Thus, there are now two private offering the rule 146 exemption and the exemption which exists outside the rule. iiJ 32 Rule 146 provides that if the offering is made in accordance with all of the conditions of the rule, then it shall be deemed to 148 be a transaction not involving any public offering. Although the rule provides a safe-harbor for issuers who comply with its conditions, these conditions can be burdensome. For some149 issuers not subject to the reporting requirements of the 34 Act, the burden of com- plying with rule 146 is nearly as great as registration under section 5, but with less predictability. Those issuers who are subject to the reporting requirements of the 34 Act, however, should find the rule's disclosure requirement easy to satisfy. Accordingly, although the small issuer may find it necessary to seek refuge under some other exemption, the larger corporations that are subject to the 34 Act's reporting requirements should find the rule 146 exemption 150 attractive. To achieve the safe-harbor that rule 146 provides, however, the issuer must strictly comply with all of the rule's conditions, and even an immaterial breach will cause the offering to fail under rule 146. 152 In a situation where the issuer has made a good faith attempt to comply with rule 146, it is likely that the exemption out153 side of the rule will be available. In fact, this may be the area in which the exemption outside of the rule is primarily relied on. Therefore, although the all or nothing requirement of rule 146 seems overly onerous, the nonexclusive nature of the rule should effectively ease this burden. Even though the standards of rule 146 are far more precise than those which exist outside of the rule, the practitioner may find it necessary to solicit the SEG's opinion on any ambiguities which arise 33 under the rule. The SEC has made it clear that it will assist in 154 this matter by issuing interpretative letters. Thus, when in doubt the prudent practitioner should seek the advice of the SEC. As previously noted, rule 146 is not the exclusive means by which an issuer can qualify for the private offering exemption. The issuer can qualify for the exemption outside of rule 146 by complying with the judicial and administrative interpretations of section 155 4(2). " Complying with the judicial and administrative interpre- tations of section 4(2), however, is not an easy task. It was the confusion which existed under the section 4(2) exemption which prompted the SEC to adopt rule 146. Accordingly, the practitioner who seeks to engineer a private offering outside of rule 146 faces the same problems which the SEC sought to alleviate with rule 146. While the SEC has indicated a willingness to assist practitioners by issuing interpretive letters in reference to the operation of rule 146, it has not shown such compassion for those issuers operating outside of the rule. "Although the staff will continue to con- sider no-action requests relating to section 4(2) of the Act, such letters will only be issued 157 infrequently and only in the most compelling circumstances." Thus, unless compelling circumstances exist, the issuer operating outside of the rule must be prepared to interpret for itself any ambiguities which exist under section 4(2). The availability of the exemption outside of rule 146 is unclear. Some commentators contend that the private offering exemption is still alive and well outside of rule 146/^ These commentators believe that too much emphasis is put on dicta from some of the cases. iiJ They contend that the offerings in these cases would not have 34 ] 59 qualified ariywav, and that the dictum was unnecessary, " Others, however, would point to the language of the courts which use the conditions of rule 146 as a "frame of reference" for defining the exemption outside of the rule, saying that the exemption outside 160 of rule 146 is close to nonexistent. In conclusion, although the verdict is not yet in, it appears that the exemption outside of rule 146 is for practical purposes limited to offerings to institutional investors or offerings in which the issuer has made a good faith effort to comply with rule 146. Thus, outside of these instances, as the Fifth Circuit has noted, "practitioners will be unwilling to stray from the safe harbor the rule apparently affords."'161 61 35 FOOTNOTES 1. 15 U.S.C. II 77a.~77z (1976). All references to sections or rules will be to tbe Securities Act of 1933, unless otherwise indicated. 2. 15 U.S,C. § 77e (a) (1) (1976).. 3. Section 3 of the Act, 15 U.S.C, i 77c (1976), provides that certain classes of securities are to be exempted from the section 5 requirements, Section 4 of the Act, 15 U.S.C. § 7 7d, provides that certain types of transactions are to be exempted from the section 5 requirements, 4. 15 U.S.C. § 77d (1976). 5. S.E.C. v. Ralston Purina Co., 346 U.S. 122 (1953), citing H. R. Rep. No. 85, 73d Cong., 1st Sess. 5. 6. 15 U.S.C. § 77d(2) (1976). 7. The term private offering is often used by the courts and commentators in place of the section 4(2), 15 U.S.C. I 77d(2) (1976), phrase "transactions by an issuer not involving any public offering." 8 II- 9. Note, Reforming the Initial Sale Requirements of the Private - Re P- No- 85, 73d Cong., 1st Sess. 1 (1933). Placement Exemption, 86 Harv. L. Rev. 716 (1972). 10 • E- 85, 73d Cong., 1st Sess. 5 (1933). 11. S.E.C. Securities Act Release No. 285, at 1 (Jan. 24, 1935). 12. S.E.C. Securities Act Release No. 285, at 1 (Jan. 24, 1935. 13. 95 F.2d 699 (9th Cir. 19 38), iiJ 36 14 Id. at 701. 15 Id. at 701. 16 346 U.S. 119 (1953). 17 Prior to 1964, the statutory provision for the private offering exemption was found in section 4(1) of the Act. Section 4, however, was amended in 1964 with the private offering exemption being relocated to section 4(2), Stat. 580. Pub. L. 88-467, § 12, 78 Throughout this article, for the sake of clarity, the private offering exemption will only be referred to. as the section 4(2) exemption. 18 S.E.C. v, Ralston Purina Co., 346 U.S. 125 (1953). 19 Id. at 127. 20 Id. at 125. 21 22 23 Id. at 119. 24 Id. at 125 n.11, quoting Nash v. Lynde, (1929) A.C. 158, 159. 25 R 26 The commentators and courts refer to sophisticated investors - Jennings & H. Marsh; Securities Regulation 339 (4th ed. 1977). as those who do not need the protection of the registration requirements. A sophisticated investor is not the average man on the street, but rather a businessman or attorney with a good deal of business experience. It was thought by many that wealthy persons also fell within this group. 27 448 F.2d 680 (5th Cir. 1971). 28 Id. at 690. 29 37 30. Id. 31. Id. 3?. Id. at 688 a.6. 33. 463 F.2d 137 (5th Cir, 1972). 34. 2 S. Goldberg, Private Placements and Restricted Securities § 2.16 (a), at 2-140 (rev, ed, 1978). 35. 2 S. Goldberg, Private Placements and Restricted Securities § 2,16 (a), at 2-140 (rev. ed. 1978). 36. S.E.C. v. Continental Tobacco Co., 463 F.2d 141 (5th Cir. 1972). 37. 2 S, Goldberg, Private Placements and Restricted Securities I 2.16 (c)(3), at 2-14.3. (rev. ed. 1978). 38. BNA Sec. Reg. & L.- Rep. No. 144, at R-5 (March 22, 1972). 39. S.E.C. v. Continental Tobacco Co., 463 F.2d 159 (,5th Cir. 1972), citing Hill York Corp. v. American Internat.11 Franchises, Inc. , 448 F.2d 688 n.6 (5th Cir. 1971). Not only was the citation from Hill York in a footnote based on a comment in a law review article, but it was also quoted out of context. See S. Goldberg, Private Placements and Restricted Securities § 2.. 16 (d)(4), at 2-148 2-150 (rev. ed. 1978). 40. S.E.C. v. Continental Tobacco Co., 463 F.2d 160 (5th Cir. 1972). 41. R. Jennings & H. Marsh, Securities Regulation. 342, 343 (4th ed. 1977) . 42. The first proposal of rule 146 was in SEC Securities Act Release No. 5336 (Nov. 28, 1972); it. was proposed in revised form in SEC Securities Act. Release No. 5430 (Oct. 10, 1973) and ultimately iiJ 38 iiJ adopted in SEC Securities Act Release No. 5487 (Apr. 23, 1974) Although the-"appropriate" cite to rule 146 would be 17 C.F.R. § 230.146 (1978), this form will not be used in this article. Rather, for the sake of clarity and utility, rule 146 will be referred to simply as rule 146. 43 S.E.C. Securities Act Release No. 5487 at 1 (Apr, 23, 1974). 44 S.E.C. Securities Act Release No, 5487 at 1 (Apr. 23, 1974). 45 S.E.C. Securities Act Release No. 5487 at 2 (Apr. 23, 1974). 46 Alberg & Lybecker, New SEC Rules 146 and 147: The Nonpublic and Intrastate Offering Exemptions from Registration for the Sale of Securities, 74 Colum. C. Rev. 633, 634 (1974). 47 Alberg & Lybecker, supra note 46, at 633, 634. 48 See text accompanying notes 18-25 supra. 49 Rule 146(d). 50 Rule 146(d)(1)(i). 51 Rule 146(d)(1) (ii). 52 Rule 146(d)(2)(i). 53 Rule 146(d)(2)(ii). 54 Alberg & Lybecker, supra note 46, at 636. 55 Rule 146(e). 56 See note to rule 146(e). 57 Rule 146(e)(1)(ii). 58 15 U.S.C. §§ 78a-78ii (1976) . 59 Rule 146(e)(1)(ii)(a)(1). 60 Rule 146(e)(1)(ii)(a) (1). 61 Rule 146(e)(1)(ii)(a)(2). 62 Alberg & Lybecker, supra note 46, at 640. 39 63 Rule 146(e)(1)(ii)(b). 64 Rule 146(e)(1) (ii) (b)(2). 65 Rule 146(e)(1) (b)(1), 66 Alberg 67 S.E.C, v. Ralston Purina Co., 346 U.S. 125 (1953). 68 Rule 146(g)(1). 69 Rule 146 preliminary note 3. 70 Rule 146(b)(1). 71 Rule 146(g) (2)(i)(a~c). 72 Rule 146(g)(2)(i) (d). 73 Rule 146(g)(2)(ii). 74 Rule 146 preliminary note 3. 75 Rule 146 preliminary note 1, 76 Rule 146(b). 77 Rule 146 preliminary note 1. 78 Rule 146 preliminary note 1. 79 S.E.C. Securities Act Release No, 5913 (Mar. 6, 1978). 80 In this context, commentators refers to the persons who res- Lybecker, supra note 46, at 641. ponded to the SEC's request for comment on the operation of rule 146, S.E.C Securities Act Release No, 5779 (Dec. 6, 1976). 81 S.E.C. Securities Act Release No. 5913, at 3 (Mar. 6, 1978). 82 515 F.2d 591 (5th Cir, 1975). 83 Id. at 612. 84 85 S.E.C. Securities Act Release No. 5913, at 3 (Mar. 6, 1978). 86 S.E.C. Securities Act Release No. 5913, at 3 (Mar, 6, 1978). 87 545 F.2d 893 (5th Cir. 1977), 40 88 iiJ Id. 89 Id. 90 S.E.C. Securities Act Release No. 5913, at 3 (Mar, 6, 1978). 91 S.E.C. Securities Act Release No, 5487, at 2 (Apr, 23, 1974). 92 Rule 146(c)(1), 93 Because such an advertisement is unauthorized under paragraph at 906. (c), and paragraph (b) requires that all of the conditions of rule 146 shall be met, an offering pursuant to such act will not qualify for the exemption under rule 146, 94 Rule 1.46(b). United Properties of America, (1.978 Transfer Binder) CCH Fed. Sec. L. Rep. para. 81,627 (1978). 95 Cal. Com. Code § 9504 (West). 96 See notes 16-2.4 supra, and accompanying text. 97 See notes 27-41 supra, and accompanying text. 93 S.E.C. Securities Act Release No. 5912 (Mar. 3, 1978). 99 S.E.C. Securities Act Release No. 5912 (Mar. 3, 1978). This release adopts Form 146 and describes the contents of the Form. 100 S.E.C. Securities Act Release No. 5912 (Mar. 3, 1978). 101 Rule 146(b). 102 S.E.C. Securities Act Release No. 5487, at 5 (Apr. 23, 1974). 103 S.E.C. Securities Act Release No. 5975 (Sept. 3, 1978). 104. S.E.C. Securities Act Release No. 5975 (Sept. 8, 1978). 105. See generally Alberg & Lybecker, supra note 46, and Schwartz, Rule 146: The. Private Offering Exemption -- Historical Pers- pective And Analysis, 35 Ohio State L. J. 686 (1974). 106. Alberg & Lybecker, supra note 46, at 641. 41 107 Alberg &. Lybecker, supra note 46, at 641. 108 Schwartz, Rule 146; The Private Offering Exemption -- Historical Perspective And Analysis, 35 Ohio State L. J. 763 (1974). 109 Rule 146(d)(2)(ii), 110 Rule 146(a)(1). 111 For a discussion of some of these unanswered questions, however, see Alberg & Lybecker, supra note 54, at 637, 112 Rule 146(a)(1)(i). 113 Rule 146(a)(1)(iv). 114 Pension and Investment Associates of America, Inc., (1977-1978 Transfer Binder) CCH Fed. Sec. L. Rep. para, 81,405 (1977). 115 116 117 118 Id. 119 S.E.C. Securities Act Release No. 5913 (Mar. 6, 1978). 120 Supra, note 80. 121 S.E.C. Securities Act Release No. 5913 (Sept. 8, 1978). 122 S.E.C. Securities Act Release No. 5913 (Sept. 8, 1978). 123 S.E.C. Securities Act Release No. 5913 (Sept. 8, 1978). 124 See notes 114-118 supra, and accompanying text. 125 Rule 146(g). "126 Rule 146(g)(2)(ii). 127 Rule 1.46(g) (2) (i)(d). 128 S- Goldberg, Private Placements and Restricted Securities I 10.7 (d)(4), at 10-80 (rev. ed. 1978). 42 129 Robert S. Sinn Securities, Inc., (1976-1977 Transfer Binder) CCH Fed. Sec .• L. Rep. para. 80,905 (1976). 130 131 132 Marion Corporation, (1977-1978 Transfer Binder) CCH Fed. Sec. L. Re£. para. 81,334 (1977), 133 134 PLM Inc., (1.978 Transfer Binder) CCH Fed. Sec. L. Rep. para. 81,567 (1978). 135 136 137 Rule 146(g) (2) (ii). 138 2A S. Goldberg, Private Placements and Restricted Securities § 10.7 (e), at 10-84 (rev. ed. 1978). 139 2A S. Goldberg, Private Placements and Restricted Securities 140 § 10,7 (e), at 10-84 (rev. ed. 1978). 247 F. Supp. 481 (D. Md. 1965), aff'd 376 F.2d 675 (4th Cir. 141 1966), cert, denied 389 U.S. 850 (1967). United States v. Custer Channel Wing Corp., 376 F.2d 679 (4th 142 Cir. 1966). Henry Crown Partnership, (1977-1978 Transfer Binder) CCH Fed. Sec. L. Rep. para. 81,372 (1977). 143 144 145 iiJ 43 146. S.E.C. Securities Act Release No. 5487 (Apr. 23, 1974). 147. See generally the preliminary notes to rule 146. 148. Rule 146(b). 149. Rule 146(e)(1)(ii)(b). 150. Alberg & Lybecker, supra note 46, at 643. 151. Rule 146(b). 152. Alberg & Lybecker, supra note 46, at 634. 153. Alberg & Lybecker, supra note 46, at 634. 154. S.E.C. Securities Act Release No. 5487, at 5 (Apr. 23, 1974). 155. Rule 146 preliminary note 1.. 156. S.E.C. Securities Act Release No. 5487, at 5 (Apr. 23, 1974). 157. S.E.C. Securities Act Release No. 5487, at 5 (Apr. 23, 1974). 158. Committee on Federal Regulation of Securities, Position Paper, 31 159. Law. 485 (1975). Committee on Federal Regulation of Securities, Position Paper, 31 Bus. Law. 485 (1975) . 160. See text accompanying notes 76-90 supra. iiJ