Document 13142790

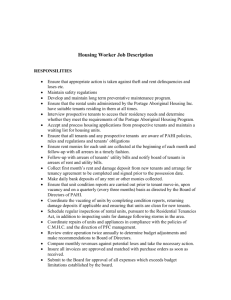

advertisement