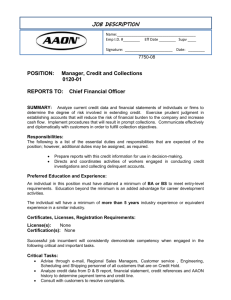

T E X A S C R E D... Erwin D . Davenport

advertisement