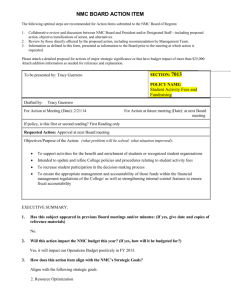

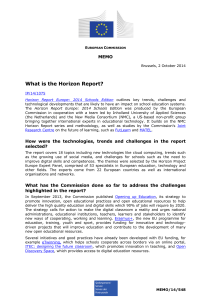

NMC Horizon Report 2013 Higher Education Edition

advertisement