The Financial Sector and the Real Economy during the Financial

advertisement

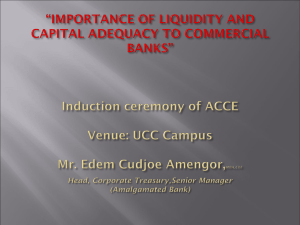

The Financial Sector and the Real Economy during the Financial Crisis: Evidence from the Commercial Paper Market Ethan Cohen-Cole University of Maryland - College Park Gustavo Suarez Federal Reserve Board Judit Montoriol-Garriga Federal Reserve Bank of Boston Jason Wu Federal Reserve Board November 19, 2010 Abstract Shocks to the …nancial sector led credit spreads to widen to unprecedented levels in many markets during the 2007-2008 …nancial crisis. The rise in spreads attracted attention because it could signal a disruption in …nancial markets, which has been widely linked to an increased burden on non-…nancial …rms. This paper disentangles the relative contributions of credit and liquidity risk in explaining the widening of commercial paper spreads. In doing so, we …nd that liquidity risk was isolated to the …nancial sector throughout the …rst two major shocks to the system (August 2007 and March 2008). Indeed, controlling for credit risk, non-…nancial corporations saw little or no change in the cost of funding during this time period. After the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers, for the …rst time, liquidity problems in the commercial paper market spilled out of the …nancial sector into the spreads of low credit quality non…nancial …rms. This e¤ect had a disproportionately larger impact on those low credit-quality non-…nancial …rms that placed paper exclusively through …nancial sector dealers. High credit quality …rms remained una¤ected throughout. Our interpretation of the results is that markets were able to di¤erentiate not only between safe and imperiled …rms in the midst of the crisis, but also to isolate where liquidity e¤ects were most likely to be salient. Ethan Cohen-Cole: Robert H Smith School of Business. email: ecohencole@gmail.com. (301) 541-7227. Judit Montoriol-Garriga: 600 Atlantic Avenue, Boston MA. email: judit.montoriol-garriga@bos.frb.org. Gustavo Suarez Federal Reserve Board of Governors. email: gustavo.a.suarez@frb.gov. (202) 452-3011. Jason Wu Federal Reserve Board of Governors. email: jason.j.wu@frb.gov. (202) 452-2556. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily re‡ect those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston or the Federal Reserve System. 1 Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1712442 1 Introduction Commercial paper spreads widened to unprecedented levels in many …nancial markets during the 2007-2008 …nancial crisis. For example, according to data from the Federal Reserve, the spread over the fed funds rate paid by A2/P2-rated non-…nancial …rm to issue overnight commercial paper increased from 60 to 400 basis points during the week following the Lehman Brothers’bankruptcy. The rise in spreads attracted a great deal of attention, because disruptions in …nancial markets are widely believed to tighten credit conditions for non-…nancial …rms. Although this unprecedented widening of spreads has been extensively documented, there is little consensus on its contributing factors. Our paper has two core aims. First, we provide a set of empirical results that contribute to the discussion on the relative importance of credit risk and the liquidity risk of very short-term commercial paper during the …nancial crisis. Second, we use these empirical results to shed light on the role of …nancial intermediaries in transmitting …nancial shocks to the real economy. To accomplish the …rst objective, we study changes in spreads around the time period of three large shocks to the …nancial system: investors’realization of the large scope of subprime-related losses in bank balance sheets in August 2007, the distressed purchase of Bear Stearns in March 2008 and the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers in September 2008. To achieve the second objective, we test a number of channels for the transmission of shocks around each of the three events. For each of the three events, we distinguish between (a) …nancial and non-…nancial issuers, (b) paper placed through a dealer and paper placed directly to the market, and (c) by issuer credit rating. With these three dimensions, we are able to precisely evaluate which set of …rms were impacted by the shocks that hit the …nancial sector and which were relatively unscathed. Our criterion for the transmission from the …nancial sector will be the degree to which non-…nancial …rms saw …nancial sector shocks impact the liquidity component of their own borrowing rates. Where we observe that changes in credit quality alone explain spread changes of non-…nancial 2 Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1712442 …rms, even around a large event, we will make the claim that there is little transmission.1 For our empirical work, we focus on unsecured commercial paper of 1-4 day maturity. Commercial paper is a signi…cant source of short-term debt …nancing for a wide range of …rms. This market provides …nancing to …nancial …rms and corporations typically for less than 3 months, and a significant fraction has a maturity of just a few days. Analyzing the credit spreads on the shortest-term corporate debt is of special interest, because it allows us to abstract from changes in the slope of the yield curve and term premia. Although one may argue that only liquidity risk matters for such short maturities, Covitz and Downing (2007) show that, even for very short-term spreads, credit risk is important in the commercial paper market. Another practical reason for using the shortest maturity paper is that issuance of longer duration commercial paper was most a¤ected during the …nancial crisis, and only the highest quality …rms were able to issue longer term paper. Therefore, issuer selection is less severe in the shortest maturity paper. The outstanding total commercial paper balance in July 2007 was $2.1 trillion, including $1.2 trillion of asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP). By the end of June 2009, the outstanding balance had dropped to $1.28 trillion, a collapse of about 40% of the market. It is important to understand the relative scale of liquidity versus credit factors in interest rate spreads for various reasons. On the one hand, it is important for investors’ portfolio allocation decisions. The increase in spreads may represent increased compensation demanded by risk-averse investors as the credit risk on the assets increases, or alternatively could represent the premium demanded to hold more illiquid assets, which would make those assets more attractive to long-term investors (Schwarz, 2009). On the other hand, understanding the relative signi…cance of credit and liquidity risk is important for designing e¢ cient policy responses to market disruptions. If liquidity is the primary problem, then the general consensus is that policy makers should direct 1 The degree of transmission has been widely debated. Chari, Christiano and Kehoe (2008) write that there was little evidence of impact on non-…nancial …rms in October of 2008. Cohen-Cole et al (2008) respond that evidence of transmission was indeed available at the time of the crisis. Bates, Kahle, and Stulz (2009) point out that non-…nancial …rms held su¢ cient cash stock piles prior to the crisis to have paid o¤ existing debt, obviating the need for …nancing. 3 e¤orts to restoring market con…dence to make markets more liquid.2 If credit risk is the main determinant of credit spread widening, then policy makers can either improve the solvency of the counterparties involved or allow the market to reallocate credit independently. In theory, in the absence of liquidity concerns, there is limited scope for intervention. In practice, the distinction between these two explanations is not clear-cut, since liquidity shortages may be a by-product of credit problems, and the solution is no longer as simple as restoring con…dence. As we shall see below, our results suggest that the transmission of liquidity shocks from …nancial intermediaries to some non-…nancial …rms may emerge from credit concerns. We provide evidence in this paper that the spike in credit spreads in the short-term commercial paper market was a combination of a liquidity and credit crisis. More importantly we show that the liquidity risk was largely isolated to the …nancial sector throughout the …rst two major shocks to the system (August 2007 and March 2008). Indeed, controlling for credit risk, non-…nancial corporations saw little or no change in the cost of funding during this time period. Liquidity problems in the commercial paper market spilled out of the …nancial sector into the spreads of low credit quality non-…nancial …rms for the …rst time after the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers. This e¤ect had a disproportionately larger impact on those low credit-quality non-…nancial …rms that placed paper exclusively through …nancial sector dealers. Issuance cost of commercial paper of high credit-quality …rms remained una¤ected throughout.3 Our interpretation of the results is that markets were able to di¤erentiate not only between safe and imperiled …rms in the midst of the crisis, but also to isolate where liquidity e¤ects were most likely to be salient. Non-…nancial …rms that were of good credit quality and / or had some direct access to capital markets were able to sidestep the liquidity shocks that hit the …nancial sector. In contrast, non-…nancial …rms with credit or potential credit exposure experienced sharply increased 2 See Allen, Carletti and Gale (2009) and Krishnamurthy (2010) for examples and literature review. Our emphasis in on the immediately e¤ects of the …nancial shocks on the funding costs of …rms. As the recession continued, many parts of the economy were impacte by a myriad of factors. Our di¤erence-in-di¤erence approach that we discuss in detail below is designed to isolate the impact of the large shocks on commerical paper spreads. 3 4 credit risk sensitivity after August 2007, especially if they were using a dealer to place paper in the market. Jointly, our …ndings highlight the manner in which the …nancial sector transmitted shocks to the large non-…nancial corporations that are the typical commercial paper users. For the …rst year following the initial shock in August 2007, almost no transmission occurred. However, once the largest shock hit in September 2008, the stress on the …nancial sector was su¢ cient that the spillover to the non-…nancial sector occurred, a¤ecting most the lower quality …rms and dealer users. This suggests that the transmission of the shocks from the …nancial sector to the real economy occurred through intermediated services to low credit quality …rms. Our results show that the principal risk faced by …nancial …rms was the ability to rollover their short-term debt. Of course, in the medium run, many of the banks’ holdings of bad debt may have led to credit problems as well, but, at the time of the strongest shocks to the market during the crisis, the critical problem for …nancial institutions appears to have been liquidity. Our results are in contrast with those of Afonso, Kovner and Schoar (2010), who document that counterparty risk played a much more important role than liquidity hoarding in the interbank market during the 2008 …nancial crisis. Their interpretation of the results is that lenders in the fed funds market were able to screen out the worst performing borrowers. Our results suggest that investors in the commercial paper market demanded a higher premium to invest in …nancial commercial paper due to increased liquidity risk, not credit risk. However, it is important to note that the di¤erence in results may be due to the fact that commercial paper and fed funds are di¤erent markets, and the …nancial …rms participating in each one may di¤er. The …ndings in this paper have implications for the debate on the importance of the …nancial sector for the real economy. The continued economic sluggishness more than three years after the initial subprime shocks of August 2007 has repeatedly been attributed to the lack of debt …nancing 5 from the commercial banking sector.4 As the crisis struck, the widespread interpretation of the stress in credit markets was that a lack of liquidity led to the inability for essentially all market participants to roll over obligations. Given that the initial …nancial shock was concentrated in the banking sector, one could expect that bank-dependent …rms would be most a¤ected by this shock. On the other hand, non-…nancial corporations that issue commercial paper should be somewhat isolated from the shock in the banking system since these larger …rms have the ability to access capital markets. In this paper we present evidence on an often neglected link of the …nancial and non-…nancial sectors, which is that many non-…nancial commercial paper issuers use a dealer to place the paper into the market. An extant literature and press reports have emphasized the crucial nature of the …nancial sector for promoting economic growth. Indeed, the work of Bernanke et al (1999), as well as recent work by a range of others,5 facilitated understanding of …nancial linkages to the real sector that were not possible within classical macroeconomic models. Empirical evidence for prior crises shows that bank distress is transmitted into the real economy.6 Additionally, there is a growing literature on the empirical implications of the 2007-2008 …nancial crisis that suggest a real-economy link.7 However, there are relatively few papers that seek to understand the nature, timing and size of 4 See Cornett et al (2010), the senior loan o¢ cers survey, as well as recent press. For example, CNBC, May 27, 2010. 5 Cohen-Cole and Martinez-Garcia (2009), Faia and Monacelli (2007), Curdia and Woodford (2010), De Fiore and Tristani (2009) and many others. 6 Peek and Rosengren (2000) …nd evidence for the Japanese …nancial crisis spillovers into the US economy; Dell’Ariccia, Detragiache, and Rajan (2008) …nd evidence in a wide range of crises; Khwaja and Mian (2008) …nd evidence from an emerging market; Chava and Purnanandam (2011) …nd evidence from the Russian crisis. Borenzstein and Lee (2002) discuss Korea. 7 Ivashina and Scharfstein (2010) …nd that new loans to large borrowers fell during the crisis and provide some evidence that liquidity constrained banks may have been more likely to cut lending. Campello, Graham and Harvey (2010) use a CFO survey to …nd that many corporations cut spending and investment and attribute those cuts to inability to obtain …nancing. Duchin, Ozbas, and Sensoy (2010) …nd that corporate investment declined as a result of the crisis and have evidence that the decline was a result of reduced access to funding. Additionally, a couple of recent papers analyze commercial paper during the crisis, but come to di¤erent conclusions. Kacperczyk and Schnabl (2010) …nd that the market faced a generalized collapse, and Gao and Yun (2009) …nd that declines in commercial paper use was concentrated among low credit quality …rms. Both analyze commercial paper at a somewhat higher level of aggregation than our data permit. 6 the transmission.8 This paper contributes to this literature by disentagling the pathway for the spillover from the …nancial sector to the real economy using evidence from the commercial paper market. The rest of the paper is organized as follows. We proceed in section 2 to provide an overview of the commercial paper market, principally focusing on the unsecured segment of the market. In section 3, we describe our data in more detail and discuss our empirical strategy. Section 4 presents our main results and provides some important robustness checks. Section 5 concludes. 2 Background on the Commercial Paper Market Commercial paper is a form of borrowing with a …xed maturity, typically between 1 and 270 days. The paper is issued by banks, large corporations, and special purpose vehicles to meet short-term …nancial obligations including operational needs such as payroll, or for the purchase of assets. Commercial paper is viewed as an inexpensive funding option by banks and corporations alike. Prior to the crisis, it was relatively simple for large corporations to access the commercial paper market, and regular funding could be obtained at rates lower than bank loans and without the fees associated with a guaranteed line of credit. However, many issuers maintain a line of credit to provide additional access to capital. Commercial paper can broadly be classi…ed along a few dimensions. Among these are the presence of collateral, the type of issuing …rm and the issuance channel (see Hahn, 1998, for a description of the commercial paper market). Our paper focuses principally on unsecured (uncollateralized) commercial paper issued across a range of channels. By evaluating unsecured paper, we are able to isolate the impact of the credit quality of the issuer from the role of liquidity shocks without explicit modeling of the underlying asset quality. That is, we can rely on credit quality estimates of the corporate commercial paper sponsor as a reasonable proxy for credit-worthiness. 8 A recent exception is Tong and Wei (2009). 7 A comprehensive overview of the asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP) market and its operation during the crisis can be found in Covitz, Liang and Suarez (2009). Within the commercial paper markets, we will look at the issuance of commercial paper across both …nancial and non-…nancial …rms. Non-…nancial and …nancial corporations alike used the commercial paper market as a highly liquid and readily accessible short-term funding. Anecdotally, these markets grew in popularity both because borrowing costs were somewhat lower than equivalent corporate loans and because commercial paper is, in general, junior to secured debt. The use of commercial paper by …nancial and non-…nancial …rms di¤ers substantially. Non-…nancial …rms typically use commercial paper to fund on-going cash ‡ow needs such as payroll and inventories. As a result, interruption of access to these markets could lead to an inability to manage regular operations and cause layo¤s and supply disruptions, which could potentially lead to severe disruptions to the real economy. Financial …rms use commercial paper to manage short-term liquidity needs, including maturity mismatch in assets and liabilities, or in some cases to fund large portions of their balance sheet. With respect to the methods of issuing paper, an issuer can either sell securities directly in the money markets or it can sell them to a dealer. The dealer subsequently sells the paper in the market. Dealers are typically large banks and bank holding companies, including the investment banks that existed prior to the …nancial crisis. The bene…t of direct issuance is the ability to receive the full market price for the securities. However, working through a dealer institution could facilitate issuance if the institution has strong distribution networks. We will highlight this distinction throughout our empirical analysis. A buyer of corporate commercial paper from a dealer assumes the risk of corporate default during the term of the commercial paper as well as the counterparty risk of the dealer during the settlement time period between purchase …nal settlements. This risk prior to the crisis was negligible, but during the crisis it became large. As a result, issuers that relied on dealers faced the possibility that liquidity 8 concerns at the dealer banks would impact the spreads on their own issuances. Below, we provide empirical support for this link. 3 Data Our initial dataset includes all 91,589 primary market issues in the unsecured commercial paper (CP) market in the U.S. market between January 1, 2007 and December 31, 2008. This includes information on 353 programs. These data are obtained from the Depository Trust and Clearing Corporation (DTCC), the agent that electronically clears and settles directly- and dealer-placed commercial paper. The issues in the sample are discount instruments paying face value at maturity. For each transaction, DTCC provides the identity and industry of the issuer, the face and settlement values of the transaction, and the maturity of the security. Using this information, we calculate yields on new paper based on the assumption of a 360-day year. We also obtain from DTCC a separate weekly …le that contains program level information on the maturity distribution of outstanding paper. Further, we supplement the DTCC data with information on program type, credit ratings, liquidity features, and sponsor identity from various reports from Moody’s Investors Service. We have four key variables for our study: Overnight CP spread We use the spread over the fed funds rate for commercial paper maturing in 1-4 days. We choose the shortest term commercial paper to ensure that we can evaluate the trade-o¤ between liquidity and credit risk without concern for yield curve impacts, duration or other issues. Another practical reason for using the shortest maturity paper is that issuance of longer dated commercial paper was most a¤ected during the …nancial crisis, and only the very high quality …rms were able to issue longer term paper. Therefore, issuer selection is least severe for the shortest maturity paper. CDS Spread 9 We supplement data on commercial paper transactions with measures of credit and liquidity risk. For our credit risk measure, we obtain 5-year CDS spreads for each commercial paper issuer from Markit Partners. A CDS spread is a fraction of the CDS contract notional paid from the buyer to the seller in return for credit protection on debt obligations, in the case where the issuer defaults. For each day, we average CDS spreads of senior unsecured debt across four primary types.9 CDS spreads are generally regarded as real-time market-based measures of credit risk. While there is some evidence that they contain a liquidity component, its importance appears to be small in magnitude (Tang and Yan (2007), Lin, Liu and Wu (2009)). Fraction of paper maturing in following week For our liquidity measure, we calculate the fraction of total liabilities maturing in the upcoming week using information provided by DTCC. This measure provides a proxy for the issuer’s need for liquidity in the short run that re‡ects the maturity of its liability in the absence of credit quality concerns. Fraction of dealer-placed paper. To account for the role of dealer intermediation in this market, we calculate the percentage of each program’s issuances that is placed through a dealer. Later in the paper, we will subdivide the sample to evaluate the di¤erence between programs that exclusively place their paper through dealers and those that directly sell at least some of their own paper. Table 1 summarizes our dataset by subperiod. The …rst four columns show summary statistics for the full sample period, January 2007 to December 2008. The subsequent columns show summary statistics for commercial paper issuances for the three subperiods of our analysis: January to 9 The four classes are the standard International Swap and Derivatives Association (ISDA) classi…cations. Class 1 is "No Restructuring": This option excludes restructuring altogether from the contract, eliminating the possibility that the protection seller su¤ers a “soft” credit event that does not necessarily result in losses to the protection buyer. Class 2 are "Full restructuring" contracts. These allow the protection buyer to deliver bonds based on any debt restructuring. Classes 3 and 4 are "Modi…ed Restructuring" and "Modi…ed Modi…ed Restructuring" contracts. These are full restructuring contracts that limit the bonds that can be delivered to <30 months and <60 months respectively. 10 December 2007 (encompassing the crisis in funding markets that erupted in August 2007); January to June 2008 (encompassing the distressed purchase or Bear Stearns in March); and July to December 2008 (encompassing the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers in September 2008) . Each panel provides summary information for the core four variables used in the study plus two additional liquidity measures that we will address below. We report the mean, standard deviation, minimum and maximum for each variable for each time period. We also report the number of commercial programs that appear in each sample, as well as the number of observations (issuances) in each case. 4 Empirical Strategy and Results The aim of this paper is to disentangle the relative contributions of credit risk and liquidity risk in the widening of unsecured commercial paper spreads of maturity 1 to 4 days during three major events in the 2007-2008 …nancial crisis: the initial shock of August 2007, the failure of Bear-Stearns on March 14, 2008 and the failure of Lehman Brothers on September 15, 2008. Second, we wish to understand how the importance of credit and liquidity risk depends on the issuance channel. Finally, we want to investigate whether issuers in the …nancial sector were impacted di¤erently than those outside of it. Our analysis of the commercial paper using a combination of these criteria enables us to shed some light on the following general questions: 1. Was the …nancial crisis a liquidity or credit event? 2. Does this distinction help us understand the transmission channel from the …nancial to the real economy? 3. Was the market able to distinguish between imperiled companies and safe ones? We show in Figure 1 the stylized patterns of commercial paper issuance. Each box represents a type of issuer. Trapezoids represent the presence of a dealer in a transaction. The ovals at the 11 bottom of each diagram are investors that buy commercial paper. The connecting lines represent an active channel, and the black lines across a channel indicate increased costs via this channel due to liquidity premia. Panel A shows the situation pre-crisis, where all channels are operational. Panel B shows the situation in a generalized liquidity crisis, where all channels have been severed. Panel C shows what one would expect if non-…nancial issuers could continue to issue; e¤ectively the situation in the absence of a …nancial sector transmission mechanism. Panel D shows our stylized results in the paper, where …nancial issuers su¤er liquidity shocks and non-…nancial issuers are impacted via dealer networks, but direct market access remains open. [Insert F igure 1 here] We conduct regressions of CP spreads on a variety of controls for …rm-level credit risk, CP instrument liquidity and events that impacted the entire market. For identi…cation, we use a di¤erence-in-di¤erence approach. We conduct a series of event studies around the three events: the subprime credit losses of August 2007, the collapse of Bear Stearns in March 2008 and the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008. We subdivide our sample of data in three time periods, each surrounding one of the events. For the August 2007 shock that started the crisis, we include data from January to December of 2007. The full year is included here in order to ensure that we have a su¢ cient baseline of activity leading up to the crisis. For the Bear Stearns collapse, we include data from January 2008 to June of 2008. This includes both the period of relative calm at the beginning of the year as well as a return to relative calm in mid-year. Finally, for the Lehman case, we include data from mid-year 2008 until the end of 2008. For each episode, we include a dummy variable to mark the crisis time period. This is coded as a one during the times of stress and a zero otherwise. That is, we …nd a period of 20 trading days (one month) before and after August 9th, 2007, March 14th, 2008 and September 15, 2008. We then subdivide the sample of commercial paper issuance along the …nancial/non-…nancial and dealer/direct dimensions. These steps allow us to use a di¤erence-in-di¤erence-in-di¤erence 12 approach along three axes: Financial vs non-…nancial …rms. This distinction permits us to analyze the di¤erential impacts of the crisis on the …nancial and real economies. Pre-shock vs post-shock. With this approach, we are able to determine the impact of the shock on the indicated sub-sections of the economy for each of the three shocks mentioned. Dealer placed vs direct issuance. By looking at dealer placement, we can shed additional light on the role of intermediation functions on the impact of the crisis. At the end of the paper, we will complement the analysis by looking more deeply at the highest credit quality …rms. 4.1 Results We begin with an exploration of the impact of three …nancial crisis events on CP spreads. In particular, we look at the contribution of our liquidity and credit proxies as each of the crisis events hit the markets. We can begin with a regression of spreads on two controls independent of event dummies. spreadit = + 1 1 creditit + 1 2 liquidityit + i + eit (1) for all companies i in time t. The variable spreadit is the 1 day commercial paper spread. credit1it 1 is our …rst liquidity proxy: fraction of is our …rst credit variable, average 5-yr CDS, and liquidityit outstanding commercial paper due in the upcoming week. We also include program dummies, i, thereby adding …xed e¤ects to the model. We interpret a positive liquidity coe¢ cient as representing heightened sensitivity to short-term funding needs. A positive coe¢ cient on the credit variable suggests increased credit risk premia. Table 2 shows the results of this speci…cation. We can see in the top two rows and the …rst three columns that a …rst order impact of the crisis was to increase spreads due to both credit and 13 liquidity. These e¤ects are present, large and strong in nearly all speci…cations. [Insert T able 2 here] Table 2 also includes issuer and date-level …xed e¤ects at the …rm level and marks whether the regressions have been estimated with heteroskedasticity consistent standard errors. In subsequent tables, we will use only the speci…cations that have issuer …xed e¤ects and robust standard errors. Issuer …xed e¤ects are important to controlling for idiosyncratic di¤erences across programs. We don’t include date …xed e¤ects to avoid problems of collinearity, as our spread information is also at a day level. Additional results including these other possibilities are available on request. Baseline We can now turn to our primary speci…cation. As mentioned, we include dummies for each of the three events. The interaction of the dummies for the stress time periods with the credit and liquidity variables provides the basis for inference. spreadit = + 1 1 CRit + 1 2 LIQit + k 3 T Dt + 4T D k CRit + 5T D k LIQit + i + eit (2) where T Dtk is a dummy coded 1 during the time period after the event k and zero otherwise. The variables T Dk CRit and T Dk LIQit are the interactions between T Dtk and the relevant credit and liquidity variables de…ned above. For the speci…cations we showed in Table 2, as well as in future tables, we will code the dummy as 1 for the one-month period after the event in question. Our speci…cations will include two months of data for each event, one month prior and one month post event. For the three large shocks, August 9, 2007, March 14, 2008 and September 15, 2008, we de…ne a dummy variable as above, T Dtk where k indexes the three events: k = 1 : August 9, 2007; Subprime shock k = 2 : March 14, 2008; Bear-Stearns default k = 3 : September 15, 2008; Lehman bankruptcy 14 Table 2 continues after column 4 to show the results of regression 2 using the credit and liquidity proxies as well as the event dummies. This table makes clear that each of the three events had aggregate impacts on the economy. Subsequent tables will delve into the details of the events in order to address the substantive questions outlined above. Then, for each of k = 1; 2; 3, we run regression 2 and add the interaction of the event dummies and the credit and liquidity variables in table 3. In this table as well as subsequent ones, we have omitted date …xed e¤ects both to avoid collinearity problems with the events themselves and for brevity. These results are available on request from the authors. [Insert T able 3 here] Of particular note in table 3 is that both the credit and liquidity proxies are strongly positive and signi…cant in the …rst two event time periods. The liquidity variable is strongly signi…cant and positive in Lehman event time period. This result is consistent with interpretations of the crisis that found that liquidity was at a large premium and that risk premia increased sharply. By the time we reach the Lehman crisis, the markets have become strongly attuned to liquidity concerns, and the coe¢ cients suggest that this was the primary e¤ect. We will expand the analysis in equation 2 by analyzing in the three ways described below with the goal of answering our primary question. 4.2 The Financial Sector We can move now to an analysis of the impact of the three crisis events on spreads across types of issuers. As was widely publicized, the crisis was originally in the …nancial sector itself. As a result, a key method to determining whether the liquidity shocks were generalized is to observe di¤erences in spread changes across …nancial and non-…nancial …rms. This di¤erence is important for understanding the role of the …nancial …rms in impacting the real economy. Referring to Figure 1 again, we can illustrate a basic interpretation of coe¢ cient 15 combinations across …nancial and non-…nancial …rms. In addition to interpreting the simple liquidity and credit coe¢ cients, the schematic infers from the combination of coe¢ cients the possible interaction between the two sectors. Speci…cally, sets of positive coe¢ cients for all combinations implies, as in table 3, that the economy faced generalized distress. However, mixed sets of coe¢ cient imply di¤erential responses to the crisis. We extend equation 2 above by estimating the speci…cations on the subsamples of the …nancial sector and the non-…nancial sector commercial paper programs. The two sets of results are shown in table 4. We have included the full sample results as well for comparability. As in the previous tables, we show the results for each of the three events separately, arranged in chronological order. [Insert T able 4 here] In table 4 we observe a number of notable features. First, the generalized shocks that appeared in table 3 are signi…cantly di¤erentiated across the sectors. In some of the events, one of the two variables is insigni…cant for one of the two groups. Even before discussion of the nature of the distinction, this implies that the impact of the crisis was distinct across sectors; that is, the market was able to distinguish the impact of the crisis with some degree of precision across sectors - even during the Lehman event. This is in sharp contrast to the notion that the market as a whole froze. Second, the pattern of di¤erentiation provides evidence that the …nancial sector faced principally a liquidity shock, and the non-…nancial sector principally a credit shock. We have shaded the coe¢ cients that indicate this pattern in table 4. Notice that in each of the three events, the non…nancial sector saw a signi…cant credit shock. Indeed, the sector only faced a liquidity shock at the Lehman bankruptcy event. Below we will provide some additional detail on this component to show that only a portion of the non-…nancial sector saw this shock. On the other hand, the …nancial sector saw a liquidity shock in all three and only saw a credit e¤ect during the Bear Stearns collapse. 16 We take the fact that these simple proxies are able to di¤erentiate the e¤ect during such enormous disruption as strong evidence that the market was able to di¤erentiate …rms in purchasing commercial paper. That is, our proxies are a single measure of …rm liquidity needs and credit quality. While we cannot be certain of investor behavior, one might hope that investors would use more than a CDS spread and the fraction of maturing paper to make lending decisions. If so, we would expect to see even greater levels of di¤erentiation. The distinctions that we observe imply that the generalized disruption was more orderly than previously thought. Indeed, notice that this interpretation is distinct from a ‡ight-to-quality, panic scenario. Rather, it re‡ects a market that was able to use available information to make reasonable lending decisions even in the midst of one of the largest …nancial disruptions in history. Additionally, the pattern facilitates understanding of the role of the …nancial sector in the real economy. During normal times, the …nancial sector provides intermediation services and access to funding for real-economy …rms. Our results suggest that the shocks faced during this large crisis led to dramatically increased liquidity premia at …nancial …rms, but had little direct liquidity impact on non-…nancials. Indeed, the market appears to have been able to segregate non-…nancials according to their credit risk. This increased sensitivity to credit risk for non-…nancial …rms indicates that market events had a heterogeneous impact on non-…nancial …rms. While low credit quality …rms experienced increased spreads, high credit quality …rms continued to receive short-term funding. E¤ectively, the runs that occurred in the repo markets (Gorton and Metrick (2009) and many others) and the ABCP markets (Covitz, Liang and Suarez (2009)) were phenomena isolated to …nancials. The maturity mismatch at non-…nancials did not lead to funding withdrawals, at least for the highest quality …rms. In order to further check this interpretation of the results, we will run a robustness check only looking at A1/P1 issuers (see results below). 17 4.3 The Role of Dealers One heightened concern during the crisis was the …nancial condition of intermediating banks. Indeed, this connection is the basis for concern that a …nancial sector shock impacts the real economy. Without …nancial intermediaries, a real-economy …rm may be unable to obtain funds for otherwise pro…table investments. A …rm that issued its commercial paper through a dealer could potentially be perceived as being more dependent on …nancial institutions for funding and thus at greater risk during times of …nancial market distress. We test whether the market used this distinction in penalizing the funding costs of dealer-dependent …rms. A typical relationship involves the issuer placing its commercial paper through a dealer. The dealer will typically buy the paper at a discount and immediately sell it in the market. On occasion, dealers will hold some paper inventory as a service to issuers; this is often useful when issuers need funds of a particular maturity. During the crisis, if a dealer’s own access to liquidity shrunk, their ability to o¤er services would shrink as well. As a result, one might expect that issuers that were dependent on dealers would have been more susceptible to the liquidity shocks we observed above. We expand on equations 1 and 2 above by estimating the speci…cations on the subsamples de…ned according to whether the CP programs had a dealer or not. We subdivide the sample into the 100% dealer placement and <100% in order to highlight the fact that …rms with proportions less than 100% do not have fully independent access to …nancial markets and are thus potentially exposed to intermediation channel disruptions. Table 5 shows a couple of di¤erences between …rms that had 100% dealer placement and those that did not. During the …rst and second crisis events (August 2007 and March 2008) …rms that had less than 100% dealer placement saw no liquidity shock, but these …rms su¤ered an increased sensitivity to credit risk. These results suggest that issuers that use a dealer are more subject to liquidity risk than those that do not. This highlights the role of …nancial intermediaries in 18 transmitting the initial liquidity shock to other …nancial markets. Even though the commercial paper market is thought as arm’s length …nancing without …nancial intermediation, it is clear from these results that …nancial intermediaries act as dealers in many of these transactions, and, therefore, there is some risk of spillover of their liquidity problems to this market. [Insert T able 5 here] However, during the Lehman event, we observe the opposite pattern: liquidity risk is signi…cant while credit risk is not for …rms that had less than 100% dealer placement. We attribute this result to the fact that the Lehman event was characterized by widespread liquidity problems. In this event, all …rms, regardless of their use of a dealer, experience an increased liquidity premium. We will see further evidence to support this pattern below when we further subdivide the sample into low and high credit quality issuers. Firms that were 100% dealer intermediated saw a large credit and liquidity e¤ect in the three events. This is consistent with the idea that …rms without their own programs were in greater need of intermediation services. Naturally, the presence of intermediation services leads logically to a stronger transmission mechanism from the …nancial to the real economy. 4.4 Credit Quality To gain further insight into the patterns we observe, we continue by restricting our sample to the set of issuers who programs have the highest ratings (A1/P1 ratings).10 For these regressions, we …nd programs that have an A1/P1 rating at the beginning of each of the three sample periods. While we restrict the sample by credit quality, the data contain signi…cant cross-sectional variation 10 Rule 2a-7 of the Investment Company Act of 1940 limits the credit risk that money market mutual funds may bear by restricting their investments to "eligible" securities. An eligible security must carry one of the two highest ratings ("1" or "2") for short-term obligations from at least two of the nationally recognized statistical ratings agencies. A tier-1 security is an eligible security rated "1" by at least two of the rating agencies; a tier-2 security is an eligible security that is not a tier-1 security. 19 in CDS spreads even within the high-quality issuers. This variation allows us to draw inference within this sample. In table 6 we present the results for …nancials and non-…nancials and in table 7 the results for the dealer and non-dealer programs. [Insert T ables 6 and 7 here] In table 6 we …nd qualitatively similar results to table 4; however, most of the coe¢ cients are smaller in magnitude. Note that these regressions include only the highest quality programs, and, therefore, the credit risk is less severe in this sample. Nonetheless, we see that changes in risk are internalized by the market and impact issuer spreads. We take this as evidence that the market was able to distinguish the credit quality di¤erences among the highest quality issuers, even in the midst of signi…cant market turmoil. With the crisis events, the credit risk premium increased for low quality non-…nancial …rms, but to a lesser extent for the highest quality …rms. In table 7 we observe that 100% dealer intermediated A1/P1 saw no liquidity shock in any of the three stages of the crisis. This result is particularly salient. The highest quality issuers, even those that had intermediation services exclusively by dealer, did not experience liquidity e¤ects at any point during the crisis. These contrast with the results in table 5 in which liquidity was signi…cant for all three events for the dealer programs. By restricting the sample to the highest quality programs, we …nd that the market demanded a higher liquidity premium only for the lowest quality programs and only if they were dealer intermediated. We also observe that the coe¢ cients on the credit risk and liquidity risk during the three market events are smaller in table 7 than in table 5, suggesting that the increased credit and liquidity premiums in the crisis were smaller for the highest quality programs than the lower quality programs. Our intuition from this …nding is that the liquidity shocks that occurred throughout the crisis emerged in part from credit quality concerns. Thus, even though we are able to separate out 20 liquidity and credit components from spreads, the core reason for the presence of a liquidity premium indeed lies in credit. 5 Conclusions This paper provides empirical evidence of the relative contributions of credit risk and liquidity risk in the widening of unsecured commercial paper spreads of maturity 1 to 4 days during three major events in the 2007-2008 …nancial crisis. Our …ndings are nuanced in that we …nd that initial …nancial sector shocks had little impact on corporate issuers and that the Lehman event passed through the dealer channel to struggling …rms. These …ndings suggest a deeper and more complex set of relationships between the …nancial sector and the real economy. Indeed, our conclusion is that the real economy is highly resilient, but not impervious, to …nancial sector distress. Non-…nancial …rms managed to withstand even the large shocks faced by …nancial …rms in the …rst year of the crisis, shocks that, at the time, were being described as unprecedented. Had the crisis ended earlier, our paper could have concluded that there are little or no transmission e¤ects, even for the largest shocks. With hindsight, and the presence of the enormous Lehman shock, we see that the transmission e¤ect to the real economy indeed exists. However, it appears to manifest only under the most extreme events and along certain channels. This nonlinearity lends credence to the story that the disintermediation of banks and …nancial companies has supported the ability of non-…nancial …rms to succeed. This nonlinearity exists due to the presence of low credit quality …rms. That is, the liquidity shocks that impacted the real economy did so on the margin of impacting lower quality …rms’borrowing rates. In the end, there appears to have been little risk to the cost of funds of high credit quality …rms. While this study has found detailed evidence of the transmission channel of the …nancial sector, we do not explore some dimensions of this question. Our study looks at the cost of funding of commercial paper issuers, conditional on their participation in the market. We encourage future 21 study in the determinants of market participation and the potential impact of the …nancial sector on those decisions. References [1] Afonso, Gara M., Anna Kovner, and Antoinette Schoar, 2010, Stressed not frozen: The fed funds market in the …nancial crisis, NBER Working Paper Series, w15806. [2] Allen, Franklin, Elena Carletti, and Douglas Gale, 2009, Interbank market liquidity and central bank intervention, Journal of Monetary Economics 56, 639-652. [3] Bates, Thomas W., Kathleen M. Kahle, and Rene M. Stulz, 2009, Why do U.S. …rms hold so much more cash than they used to?, Journal of Finance 64, 1985-2021. [4] Bernanke, Ben S., 1983, Nonmonetary e¤ects of the …nancial crisis in the propagation of the Great Depression, American Economic Review 73, 257-76. [5] Bernanke, Ben S., Mark Gertler and Simon Gilchrist, 1999, The …nancial accelerator in a quantitative business cycle framework, in John B. Taylor and Michael Woodford, eds.: Handbook of Macroeconomics, Vol. 1 (North Holland, Amsterdam). [6] Borensztein, Eduardo, and Jong-Wha Lee, 2002, Financial crisis and credit crunch in Korea: Evidence from …rm-level data, Journal of Monetary Economics 49, 853-875. [7] Campello, Murillo, John R. Graham, and Campbell R. Harvey, 2010, The real e¤ects of …nancial constraints: Evidence from a …nancial crisis, Journal of Financial Economics 97, 470-487. [8] Chari, V.V., Lawrence J. Christiano and Patrick J. Kehoe, 2008, Facts and myths about the …nancial crisis of 2008, Working paper, 666, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. [9] Chava, Sudheer, and Amiyatosh Purnanandam, 2011, The e¤ect of banking crisis on bankdependent borrowers, Journal of Financial Economics 99, 116-135. 22 [10] Cohen-Cole, Ethan, Burcu Duygan-Bump, Jose Fillat, and Judit Montoriol-Garriga, 2008, Looking behind the aggregates: A reply to ‘Facts and myths about the …nancial crisis of 2008’, Working paper, QAU08-5, Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. [11] Cohen-Cole, Ethan, and Enrique Martinez-Garcia, 2008, The balance sheet channel, Working paper, QAU08-7, The Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. [12] Cornett, Marcia Millon, Jamie John McNutt, Philip E. Strahan, and Hassan Tehranian, 2010, Liquidity risk management and credit supply in the …nancial crisis, Working paper, available on SSRN. [13] Covitz, Dan, and Chris Downing, 2007, Liquidity or credit risk? The determinants of very short-term corporate yield spreads, Journal of Finance 62, 2303-2328. [14] Covitz, Daniel M., Nellie Liang, and Gustavo A. Suarez, 2009, The evolution of a …nancial crisis: Panic in the asset-backed commercial paper market, Working paper, 2009-36 Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. [15] Curdia, Vasco, and Michael Woodford, 2010, Credit frictions and optimal monetary policy. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 42, 3-35. [16] De Fiore, Fiorella, and Oreste Tristani, 2009, Optimal monetary policy in a model of the credit channel, Working paper, 1043, European Central Bank. [17] Dell’Ariccia, Giovanni, Enrica Detragiache, and Raghuram Rajan, 2008, The real e¤ect of banking crises, Journal of Financial Intermediation 17, 89-112. [18] Diamond, Douglas W., and Philip H. Dybvig, 1983, Bank runs, deposit insurance, and liquidity, Journal of Political Economy 91, 401-419. 23 [19] Duchin, Ran, Oguzhan Ozbas, and Berk A. Sensoy, 2010, Costly external …nance, corporate investment, and the subprime mortgage credit crisis, Journal of Financial Economics 97, 418435. [20] Erlich, Natalie, 2010, May 37, Banks unlikely to ease lending standards: FICO, CNBC.com, available at: http://www.cnbc.com/id/37377093. [21] Faia, Ester, and Tommaso Monacelli, 2007, Optimal interest rate rules, asset prices, and credit frictions, Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 31, 3228-3254. [22] Gao, Pengjie, and Hayong Yun, 2009, Commercial paper, lines of credit, and the real e¤ects of the …nancial crisis of 2008: Firm-level evidence from the manufacturing industry, Working paper, SSRN. [23] Gertler, Mark, and Nobuhiro Kiyotaki, 2010, Financial intermediation and credit policy in business cycle analysis, Working paper, prepared for the Handbook of Monetary Economics. [24] Gorton, Gary B., and Andrew Metrick, 2009, Securitized banking and the run on repo, NBER Working Paper Series, w15223. [25] Hahn, Thomas K., 1998, Commercial paper, in Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond: Instruments of the money market, Monograph, 105-127. [26] Holmstrom, Bengt, and Jean Tirole, 1998, Private and public supply of liquidity, Journal of Political Economy 106, 1-40. [27] Ivashina, Victoria, and David Scharfstein, 2010, Bank lending during the …nancial crisis of 2008, Journal of Financial Economics 97, 319-338. [28] Kacperczyk, Marcin T., and Schnabl, Philipp, 2010, When safe proved risky: Commercial paper during the …nancial crisis of 2007-2009, Journal of Economic Perspectives 24, 29-50. 24 [29] Khwaja, Asim Ijaz, and Atif Mian, 2008, Tracing the impact of bank liquidity shocks: Evidence from an emerging market, The American Economic Review 98, 1413-1442. [30] Krishnamurthy, Arvind, 2010, Ampli…cation mechanisms in liquidity crises, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 2, 1-30. [31] Lin, Hai, Liu, Sheen, and Chunchi Wu, 2009, Determinants of corporate bond and CDS spreads, Working paper, Conference on Financial Economics and Accounting. [32] Meier, Andre, and Gernot J. Muller, 2006, Fleshing out the monetary transmission mechanism: Output composition and the role of …nancial frictions, Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 38, 2099-2133. [33] Peek, Joe, and Eric Rosengren, 2000, Collateral damage: E¤ects of the Japanese bank crisis on real activity in the United States, The American Economic Review 90, 30-45. [34] Schwarz, Krista, 2010, Mind the gap: Disentangling credit and liquidity in risk spreads,Working paper, available on SSRN. [35] Senior Loan O¢ cer Opinion Survey, The Federal Reserve Board, available: http://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/snloansurvey/201008/chartdata.htm. [36] Tang, Dragon Yongjun, and Hong Yan, 2007, Liquidity and credit default swap spreads, Working paper, available on SSRN. [37] Tong, Hui, and Shang-Jin Wei, 2009, The composition matters: Capital in‡ows and liquidity crunch during a global economic crisis, Working paper, wp09164, IMF. 25 Investors Dealer Financial Issuer Dealer Non-financial Issuer Investors Dealer Financial Issuer C. Isolated Financial Sector Crisis: No Real Economy Effect Dealer Non-financial Issuer A. Pre-Crisis Investors Dealer Financial Issuer Dealer Non-financial Issuer Investors Dealer Financial Issuer D. Transmission of Crisis to Real Economy Through Dealer; Direct Non-Financial Access Remains Dealer Non-financial Issuer B. Liquidity Crisis Figure 1: Financial Sector Transmission Mechanism Note: Figure shows stylized patterns of commercial paper issuance. Each box represents a type of issuer. Trapezoids represent the presence of a dealer in a transaction. The ovals at the bottom of each diagram are investors that buy commercial paper. The connecting lines represent an active channel, and the black lines across a channel indicate increased costs via this channel due to liquidity premia. Panel A shows the situation pre-crisis, where all channels are operational. Panel B shows the situation in a generalized liquidity crisis, where all channels have been severed. Panel C shows what one would expect if nonfinancial issuers could continue to issue; effectively the situation in the absence of a financial sector transmission mechanism. Panel D shows our stylized results in the paper, where financial issuers suffer liquidity shocks and non-financial issuers are impacted via dealer networks, but direct market access remains open. 26 Fraction of dealer-placed paper Liquidity risk Credit risk Overnight CP spread Financial firms PANEL B Fraction of dealer-placed paper Liquidity risk Credit risk Overnight CP spread All firms PANEL A Table 1: Summary Statistics 0.399 0.628 52.776 93.064 0.172 0.900 25.950 69.239 0.309 0.736 42.118 80.562 42 42 42 42 Firms with less than 100% dealer-placed paper Overnight CP spread 0.160 0.546 Credit risk 0.788 0.996 Liquidity risk 31.502 22.977 Fraction of dealer-placed paper 53.255 40.076 8,848 8,848 8,848 42 8,560 8,560 8,560 59 10,492 10,492 10,492 48 6,916 6,916 6,916 53 0.064 0.252 33.473 50.228 0.141 0.281 48.568 100.0 0.149 0.288 51.664 92.957 0.034 0.234 25.081 67.590 0.106 0.268 41.797 80.986 0.205 0.183 25.532 38.102 0.283 0.132 29.888 0.000 0.283 0.144 31.064 21.055 0.174 0.173 13.694 39.907 0.254 0.158 29.005 33.703 34 34 34 34 55 55 55 55 47 47 47 47 42 42 42 42 89 89 89 89 3,832 3,832 3,832 34 4,711 4,711 4,711 55 5,372 5,372 5,372 47 3,171 3,171 3,171 42 8,543 8,543 8,543 89 January 2007-December 2007 Mean Std Dev Progs Obs (5) (6) (7) (8) 0.107 0.861 32.026 44.993 0.310 0.773 51.516 100.0 0.315 0.737 54.364 92.107 0.087 0.919 26.677 66.249 0.221 0.812 42.954 79.939 0.294 0.438 22.411 38.366 0.338 0.469 29.517 0.000 0.341 0.409 29.364 21.939 0.274 0.501 16.341 41.883 0.335 0.458 28.330 35.144 31 31 31 31 54 54 54 54 45 45 45 45 40 40 40 40 85 85 85 85 2,002 2,002 2,002 31 2,555 2,555 2,555 54 2,679 2,679 2,679 45 1,878 1,878 1,878 40 4,557 4,557 4,557 85 January 2008-June 2008 Mean Std Dev Progs Obs (9) (10) (11) (12) Note: Credit risk is defined as the CDS spread of the issuer. Liquidity risk is defined as the fraction of paper maturing over the next week. All variables are in percent. 59 59 59 59 48 48 48 48 53 53 53 53 101 17,408 101 17,408 101 17,408 101 101 0.844 0.832 29.426 0.000 0.781 0.695 30.099 20.701 0.604 1.165 15.240 40.435 0.725 0.921 28.471 34.563 January 2007-December 2008 Mean Std Dev Progs Obs (1) (2) (3) (4) Firms with 100% dealer-placed paper Overnight CP spread 0.463 Credit risk 0.682 Liquidity risk 53.092 Fraction of dealer-placed paper 100.0 PANEL C Fraction of dealer-placed paper Liquidity risk Credit risk Overnight CP spread Nonfinancial firms 27 0.445 1.767 29.892 50.536 1.166 1.400 53.931 100.0 1.042 1.257 53.480 94.529 0.493 2.011 26.696 65.900 0.804 1.584 41.872 80.214 0.969 1.484 20.053 40.414 1.373 1.313 28.731 0.000 1.327 1.089 28.612 16.702 1.041 1.654 16.467 42.453 1.241 1.413 27.522 35.159 36 36 36 36 54 54 54 54 45 45 45 45 45 45 45 45 90 90 90 90 2,161 2,161 2,161 36 2,147 2,147 2,147 54 2,441 2,441 2,441 45 1,867 1,867 1,867 45 4,308 4,308 4,308 90 July 2008-December 2008 Mean Std Dev Progs Obs (13) (14) (15) (16) Constant Lehman Bear Post Aug 2007 10,600 0.095 65 Observations R-squared Number of programs 10,600 0.095 65 N N Y 10,600 0.238 65 Y N Y -0.018 [0.035] 0.012** [0.005] 0.000*** [0.000] 0.229*** [0.016] 0.012 [0.016] 0 [0.000] 0.229** [0.092] 10,600 0.511 65 Y Y Y 5,081 0.066 56 N N N 5,081 0.066 56 N N Y 5,081 0.174 56 Y N Y -0.028 [0.018] 0.047** [0.020] 0 [0.000] 0.064 [0.056] 0 [0.000] 0.110*** [0.024] 0.071*** 0.071*** 0.075*** [0.007] [0.015] [0.013] 0.001*** 0.001*** [0.000] [0.001] 0.131** [0.052] 0 [0.000] 0.055 [0.040] January 2008-June 2008 (10) (11) (12) 0.131*** [0.008] (9) 0.078 [0.050] 5,081 0.781 56 Y Y Y 2,827 0.138 51 N N N 2,827 0.138 51 N N Y 2,827 0.445 51 Y N Y 2,827 0.769 51 Y Y Y 0.013 [0.041] 0.168*** [0.025] 0.168** [0.072] 2,692 0.099 56 N N N 2,692 0.099 56 N N Y 2,692 0.358 56 Y N Y -0.112 [0.102] 0.233** [0.109] 0.007*** 0.007*** 0.005** [0.001] [0.002] [0.002] 0.078*** [0.010] 2,692 0.547 56 Y Y Y -0.122 [0.172] 0.003* [0.002] 0.036 [0.039] July 2008-December 2008 (13) (14) (15) (16) 0.068 -0.167*** -0.167*** -0.110*** 0.381*** -0.224*** -0.224** [0.055] [0.010] [0.047] [0.021] [0.038] [0.028] [0.091] 0 [0.000] 0.028 [0.057] January 2007-December 2007 (5) (6) (7) (8) -0.032 -0.057*** -0.057** [0.216] [0.005] [0.021] 0 [0.001] 0.041 [0.043] (4) Note: The dependent variable is the overnight CP spread. Credit risk is defined as the CDS spread of the issuer. Liquidity risk is defined as the fraction of paper maturing over the next week. Post Aug 2007 is a dummy = 1 after August 9, 2007. Bear is a dummy = 1 after March 14, 2008. Lehman is a dummy = 1 after September 15, 2008. N N N Issuer-fixed effects? Date-fixed effects? Robust standard errors clustered by issuer? -0.082*** -0.082*** [0.007] [0.029] 0.001 [0.001] 0.002*** 0.002*** [0.000] [0.001] Liquidity Full Sample (2) (3) 0.119*** 0.119*** 0.099*** [0.004] [0.036] [0.033] (1) Credit Table 2: Baseline 28 29 8,543 0.251 89 Observations R-squared Number of programs 8,543 0.251 89 N Y -0.027** [0.011] 0.225*** [0.049] 0 [0.000] -0.085 [0.057] 0.258* [0.145] 0.004*** [0.001] 8,543 0.455 89 Y Y 0.110*** [0.026] -0.299*** [0.081] 0 [0.000] -0.066 [0.048] 0.549*** [0.112] 0.003*** [0.001] 4,557 0.262 85 N N -0.129*** [0.018] -0.014 [0.023] 0.106*** [0.019] 0.002*** [0.000] 0.116*** [0.014] 0.004*** [0.000] 4,557 0.262 85 N Y -0.129*** [0.040] -0.014 [0.055] 0.106* [0.062] 0.002** [0.001] 0.116*** [0.035] 0.004*** [0.001] 4,557 0.768 85 Y Y 0.068** [0.027] -0.011 [0.034] 0.101*** [0.028] 0.002*** [0.001] 0.100*** [0.022] 0 [0.000] January 2008-June 2008 (4) (5) (6) 4,308 0.328 90 N N -0.116 [0.077] 0.042 [0.038] 0.022*** [0.001] -0.033 [0.060] 0.080** [0.036] 0.005*** [0.001] 4,308 0.328 90 N Y -0.116 [0.224] 0.042 [0.083] 0.022*** [0.003] -0.033 [0.074] 0.08 [0.064] 0.005*** [0.001] 4,308 0.708 90 Y Y -0.217 [0.247] 0.295 [0.201] 0.021*** [0.003] 0.844*** [0.269] -0.311 [0.226] -0.006** [0.003] July 2008-December 2008 (7) (8) (9) Note: The dependent variable is the overnight CP spread. Credit risk is defined as the CDS spread of the issuer. Liquidity risk is defined as the fraction of paper maturing over the next week. Post Aug 2007 is a dummy = 1 after August 9, 2007. Bear is a dummy = 1 after March 14, 2008. Lehman is a dummy = 1 after September 15, 2008. N N -0.027*** [0.006] 0.225*** [0.023] 0.000* [0.000] -0.085*** [0.013] 0.258*** [0.035] 0.004*** [0.000] Issuer-fixed effects? Robust standard errors clustered by issuer? Constant Liquidity * Lehman Credit * Lehman Lehman Liquidity * Bear Credit * Bear Bear Liquidity * Post Aug 2007 Credit * Post Aug 2007 Post Aug 2007 Liquidity Credit January 2007-December 2007 (1) (2) (3) Table 3: Baseline with interaction terms Table 4: Financial vs Non Financial CP issuers January 2007-December 2007 ALL FIN NON-FIN (1) (2) (3) January 2008-June 2008 ALL FIN NON-FIN (4) (5) (6) July 2008-December 2008 ALL FIN NON-FIN (7) (8) (9) -0.299*** [0.081] 0 Liquidity [0.000] -0.066 Post Aug 2007 [0.048] 0.549*** Credit * Post Aug 2007 [0.112] Liquidity * Post Aug 2007 0.003*** [0.001] Credit Bear Credit * Bear Liquidity * Bear Lehman Credit * Lehman Liquidity * Lehman Constant Issuer-fixed effects? Robust standard errors clustered by issuer? Observations R-squared Number of programs -0.005 -0.132 0.100*** 0.081*** 0.119*** -0.311 0.028 -1.251*** [0.055] [0.105] [0.022] [0.021] [0.039] [0.226] [0.092] [0.258] 0 0 0 -0.001 0 -0.006** -0.008** -0.005 [0.000] [0.000] [0.000] [0.001] [0.000] [0.003] [0.004] [0.003] -0.096* -0.028 [0.050] [0.087] 0.186 0.701*** [0.129] [0.229] 0.004*** 0.002 [0.001] [0.001] -0.011 -0.106* 0.082** [0.034] [0.059] [0.035] 0.101*** 0.135*** 0.092** [0.028] [0.040] [0.039] 0.002*** 0.003** 0.001 [0.001] [0.001] [0.001] -0.217 -0.235 -0.198 [0.247] [0.201] [0.360] 0.295 0.071 0.942*** [0.201] [0.097] [0.242] 0.021*** 0.022*** 0.017*** [0.003] [0.006] [0.004] 0.110*** 0.016 0.080* 0.068** -0.03 0.112*** 0.844*** 0.287* 1.731*** [0.026] [0.012] [0.040] [0.027] [0.037] [0.034] [0.269] [0.153] [0.274] Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y 8,543 0.455 89 3,171 0.291 42 5,372 0.484 47 4,557 0.768 85 1,878 0.689 40 2,679 0.768 45 4,308 0.708 90 1,867 0.653 45 2,441 0.743 45 Note: The dependent variable is the overnight CP spread. Credit risk is defined as the CDS spread of the issuer. Liquidity risk is defined as the fraction of paper maturing over the next week. Post Aug 2007 is a dummy = 1 after August 9, 2007. Bear is a dummy = 1 after March 14, 2008. Lehman is a dummy = 1 after September 15, 2008. Robust standard errors clustered by issuer. All regressions have fixed effects. 30 Table 5: Dealer placement vs Direct placement January 2007-December 2007 ALL 100% <100% (1) (2) (3) Credit Liquidity Post Aug 2007 Credit * Post Aug 2007 Liquidity * Post Aug 2007 Bear Credit * Bear Liquidity * Bear Lehman Credit * Lehman Liquidity * Lehman Constant Issuer-fixed effects? Robust standard errors clustered by issuer? Observations R-squared Number of programs January 2008-June 2008 ALL 100% <100% (4) (5) (6) July 2008-December 2008 ALL 100% <100% (7) (8) (9) -0.299*** -0.225 -0.281*** 0.100*** 0.149*** 0.062** -0.311 [0.081] [0.142] [0.079] [0.022] [0.024] [0.026] [0.226] 0 0 0 0 0 0.001 -0.006** [0.000] [0.000] [0.001] [0.000] [0.000] [0.001] [0.003] -0.066 -0.06 -0.056 [0.048] [0.088] [0.053] 0.549*** 0.615** 0.473*** [0.112] [0.235] [0.121] 0.003*** 0.003*** 0.002 [0.001] [0.001] [0.001] -0.011 0.061* -0.054 [0.034] [0.034] [0.058] 0.101*** 0.093** 0.123*** [0.028] [0.040] [0.044] 0.002*** 0.001* 0.001 [0.001] [0.001] [0.001] -0.217 [0.247] 0.295 [0.201] 0.021*** [0.003] 0.110*** 0.116** 0.057* 0.068** 0.096*** -0.023 0.844*** [0.026] [0.044] [0.033] [0.027] [0.028] [0.039] [0.269] -1.288*** 0.034 [0.377] [0.147] 0.001 -0.013*** [0.003] [0.004] -0.347 -0.079 [0.383] [0.265] 1.239*** -0.071 [0.346] [0.145] 0.014*** 0.027*** [0.004] [0.006] 1.419*** 0.445** [0.385] [0.187] Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y 8,543 0.455 89 4,711 0.473 55 3,832 0.405 34 4,557 0.768 85 2,555 0.772 54 2,002 0.713 31 4,308 0.708 90 2,147 0.755 54 2,161 0.634 36 Note: The dependent variable is the overnight CP spread. Credit risk is defined as the CDS spread of the issuer. Liquidity risk is defined as the fraction of paper maturing over the next week. Post Aug 2007 is a dummy = 1 after August 9, 2007. Bear is a dummy = 1 after March 14, 2008. Lehman is a dummy = 1 after September 15, 2008. Robust standard errors clustered by issuer. All regressions have fixed effects. 31 Table 6: Financial vs Non Financial CP issuers - A1/P1 only January 2007-December 2007 ALL FIN NON-FIN (1) (2) (3) Credit Liquidity Post Aug 2007 Credit * Post Aug 2007 Liquidity * Post Aug 2007 Bear Credit * Bear Liquidity * Bear January 2008-June 2008 ALL FIN NON-FIN (4) (5) (6) -0.134 0.037 -0.133 0.076*** 0.060*** 0.099*** [0.089] [0.045] [0.114] [0.019] [0.020] [0.030] 0 0 0 0 0 0 [0.000] [0.000] [0.000] [0.000] [0.001] [0.001] -0.069* -0.083 -0.058** [0.035] [0.051] [0.021] 0.343*** 0.148 0.511*** [0.127] [0.128] [0.039] 0.001** 0.002*** 0 [0.000] [0.001] [0.000] -0.002 -0.073 0.079* [0.038] [0.059] [0.039] 0.077*** 0.109*** 0.058 [0.027] [0.037] [0.049] 0.001 0.002 -0.001 [0.001] [0.001] [0.001] Lehman Credit * Lehman Liquidity * Lehman Constant Issuer-fixed effects? Robust standard errors clustered by issuer? Observations R-squared Number of programs July 2008-December 2008 ALL FIN NON-FIN (7) (8) (9) -0.312* [0.181] -0.001 [0.002] 0.002 -1.109*** [0.089] [0.210] -0.007** 0 [0.003] [0.002] -0.488** -0.347 -0.628*** [0.193] [0.210] [0.152] 0.328** 0.085 0.851*** [0.160] [0.104] [0.179] 0.011*** 0.017*** 0.009** [0.003] [0.006] [0.004] 0.106*** -0.076*** -0.165*** -0.035 [0.032] [0.025] [0.053] [0.037] 0.015 [0.011] -0.021** [0.009] 0.016 [0.015] -0.140*** [0.014] 0.005 [0.011] Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y 8,543 0.455 89 3,171 0.291 42 5,372 0.484 47 4,557 0.768 85 1,878 0.689 40 2,679 0.768 45 4,308 0.708 90 1,867 0.653 45 2,441 0.743 45 Note: The dependent variable is the overnight CP spread. Credit risk is defined as the CDS spread of the issuer. Liquidity risk is defined as the fraction of paper maturing over the next week. Post Aug 2007 is a dummy = 1 after August 9, 2007. Bear is a dummy = 1 after March 14, 2008. Lehman is a dummy = 1 after September 15, 2008. Robust standard errors clustered by issuer. All regressions have fixed effects. 32 Table 7: Dealer placement vs Direct placement - A1/P1 only January 2007-December 2007 ALL 100% <100% (1) (2) (3) Credit Liquidity Post Aug 2007 Credit * Post Aug 2007 Liquidity * Post Aug 2007 -0.134 -0.127 [0.089] [0.130] 0 0 [0.000] [0.000] -0.069* -0.099** [0.035] [0.043] 0.343*** 0.471*** [0.127] [0.103] 0.001** 0.001 [0.000] [0.001] 0.039 [0.067] 0 [0.000] -0.018 [0.046] 0.066 [0.121] 0.001* [0.000] Bear Credit * Bear Liquidity * Bear Lehman Credit * Lehman Liquidity * Lehman Constant Issuer-fixed effects? Robust standard errors clustered by issuer? Observations R-squared Number of programs January 2008-June 2008 ALL 100% <100% (4) (5) (6) 0.076*** 0.108*** [0.019] [0.021] 0 0 [0.000] [0.000] 0.061** [0.025] 0.001 [0.001] -0.002 [0.038] 0.077*** [0.027] 0.001 [0.001] -0.035 [0.062] 0.088* [0.046] 0 [0.001] 0.068** [0.031] 0.073** [0.030] 0 [0.000] July 2008-December 2008 ALL 100% <100% (7) (8) (9) -0.312* [0.181] -0.001 [0.002] -1.128*** -0.008 [0.177] [0.096] 0.002 -0.007** [0.002] [0.003] -0.488** -0.680*** -0.276 [0.193] [0.171] [0.204] 0.328** 1.033*** 0.051 [0.160] [0.110] [0.106] 0.011*** 0.008 0.015*** [0.003] [0.005] [0.004] -0.140*** -0.070** -0.124*** -0.076*** 0.952*** 0.224* [0.014] [0.026] [0.042] [0.025] [0.176] [0.111] 0.015 [0.011] 0.021 [0.029] -0.012 [0.014] Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y 8,543 0.455 89 4,711 0.473 55 3,832 0.405 34 4,557 0.768 85 2,555 0.772 54 2,002 0.713 31 4,308 0.708 90 2,147 0.755 54 2,161 0.634 36 Note: The dependent variable is the overnight CP spread. Credit risk is defined as the CDS spread of the issuer. Liquidity risk is defined as the fraction of paper maturing over the next week. Post Aug 2007 is a dummy = 1 after August 9, 2007. Bear is a dummy = 1 after March 14, 2008. Lehman is a dummy = 1 after September 15, 2008. Robust standard errors clustered by issuer. All regressions have fixed effects. 33