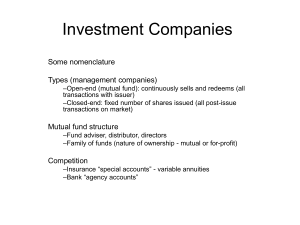

Mutual Fund Performance and Governance Structure:

advertisement