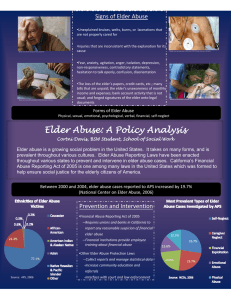

Adult Maltreatment And Adult Protecti ve Services in Central California

advertisement