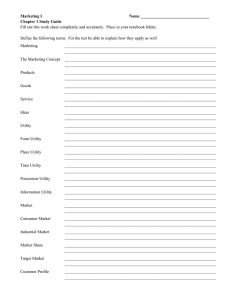

INTERPERSONAL COMPARISONS OF UTILITY:

advertisement