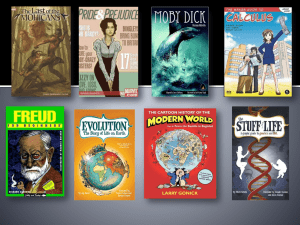

Graphic Novels across the curriculum

advertisement