The Central American Free Trade Agreement: What’s at Stake for California Specialty Crops?

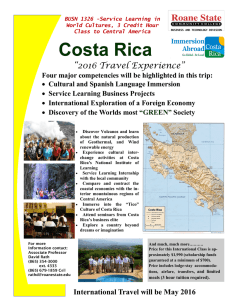

advertisement