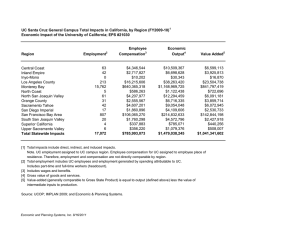

reat central valley G The State of the of California

advertisement