SECTION 1 Staff introduction

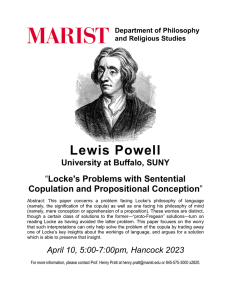

advertisement