Philosophy Moral Philosophy Higher

advertisement

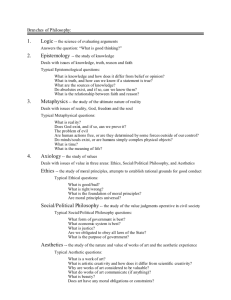

Philosophy Moral Philosophy Higher 6160 October 1999 HIGHER STILL Philosophy Moral Philosophy Higher Support Materials Contents Page 1. Teacher and Lecturer’s Guide 1 2. Student Introduction 2 3. Utilitarianism 5 3.1 Outcomes 3.2 Information section 3.3 Things to consider 4. Kant’s Ethics 11 4.1 Outcomes 4.2 Information section 4.3 Things to consider 5. Issues in Applied Ethics 17 5.1 Outcomes 5.2 Voluntary Euthanasia 5.3 Punishment 5.4 Morality of War 5.5 Things to consider 6. Suggestions for Further Reading 25 7. Guidance on Reading and Writing philosophy 27 TEACHER AND LECTURER’S GUIDE Introduction These support materials relate to the unit Moral Philosophy (H) in the Philosophy Arrangements document. Within moral philosophy there are several types of inquiry, each type corresponding to a different branch of moral philosophy. You can inquire into the sociological facts of morality, i.e., record what people’s moral values happen to be. This is called descriptive ethics, and as it is really a part of sociology or anthropology, it will not be included in our discussions in this section. Another branch of philosophy is metaethics. Metaethical discussions focus on the meaning of ethical discourse itself. Here the focus is on the definitions of moral terms (what is meant by ‘good’, ‘bad’, ‘praiseworthy’, etc.) as well as the study of how, or indeed whether, moral judgements can be justified. The distinction between subjective and objective morality is a metaethical distinction (a topic pursued in the unit Problems in Philosophy). Finally there is normative ethics, the branch of ethics to which this unit is devoted. In normative ethics the aim is to arrive at acceptable judgements of moral obligation by identifying the principles that underlie moral judgements. In other words, it addresses the question of how a person ought to behave. Teachers and students are likely to feel very much at home with the material of this unit, much more so than say with discussions concerning the definition of knowledge or Hume’s missing shade of blue. This is in all likelihood because we make moral judgements regularly, and are confronted with moral issues on a daily basis even if we do not need to make a decision concerning them. The challenge of this unit is not therefore a matter of “getting students to see the point of moral philosophy”. The challenge of this unit will be to get students thinking critically, not so much about this or that moral issue, but about theories of moral judgement. The two normative theories in ethics selected for study are Utilitarianism and Kant’s Ethics. Delivery Strategies Teachers and lecturers will have their own preferences concerning the organisation of the course and the allocation of time within it. Nonetheless the following comments may be useful. First, students are likely to find Utilitarianism easier to grasp than Kant’s Ethics, which has implications for time allocation. Second, Utilitarianism and Kant’s Ethics are ‘second-order theories’ (to be explained below), and as such they are relatively abstract. The abstractness can be overcome in at least two ways. First, relate the theories to issues in applied ethics so that they can ‘see what the theory means’ in practical terms. Second, it is often useful to discuss both theories in the same lecture or lesson, particularly at the beginning, since the contrasts serve to underline what is distinctive about both theories. Philosophy: Moral Philosophy (H) 1 2. Student Introduction Everyone makes moral judgements whether they are philosophers or not. And despite the fact that moral relativism is very common these days (the view that there is no real right or wrong, and that moral beliefs are a matter of personal opinion) this does not stop us from thinking that our judgements are in some important sense ‘right’. Nor does it stop us from getting morally outraged at the behaviour of others. But it does not take much effort to see that there are problems with this position. If there is no real right and wrong in moral matters, and we believe this, why do we think ourselves right (at least on occasion) and others clearly wrong (at least on occasion)? What do I need to know? This unit introduces you to two traditional theories in moral philosophy, and their applications to moral issues. By the end of the unit you will have become familiar with two theories in moral philosophy, and their applications to moral issues. The theories you will be studying are ‘normative theories’, that is, they are attempts to discover the principles which underlie and justify moral judgements. If some judgements are right, what makes them right? And if some actions are morally wrong, what makes them morally wrong? These are the issues you will be examining. And you will look at two of the more influential attempts to answer these questions, namely Utilitarianism and Kant’s Ethics. The moral issues will be drawn from two of the following: voluntary euthanasia, punishment and war. You will need to be able to: give an account of the essential features of the normative theories analyse them in relation to two moral issues evaluate these theories in relation to the two moral issues Philosophy: Moral Philosophy (H) 2 What are sources and how do I use them? In this unit there is mention of ‘primary’ and ‘secondary’ sources. ‘Primary’ sources are the works of recognised philosophers where the theories are treated at length; ‘secondary’ sources are works which provide commentary on the primary sources. You should refer to sources of information frequently, especially where this helps to show your understanding of a problem or issue and its various aspects. You are encouraged to use direct quotations if you can remember them, but there are also other ways of referring to texts and sources: naming the title of the source, and its author paraphrasing the source (putting the main ideas in your own words) by a combination of these methods. What skills do I need to learn and develop further? Knowledge and understanding involves providing facts, definitions, account of problems, references to source material, and any point of information which explains the main features of the selected topic accurately and to a degree appropriate to the level. Analysis involves a further stage of the examination of the theories and issues. This may mean identifying the premises and unstated assumptions used to support a conclusion, or explaining in detail the positions adopted. Evaluation involves making suitably well-supported judgements about the theories and issues. At this stage you should be in a position to consider your own attitude towards the theories and issue. Philosophy: Moral Philosophy (H) 3 Philosophy: Moral Philosophy (H) 4 3. UTILITARIANISM 3.1 Outcomes By the end of this section you should: Know something about the main proponents of utilitarianism, namely Bentham and Mill Be familiar with the basic principles of Utilitarianism Be familiar with the standard objections to Utilitarianism 3.2 Information Section Preliminary comments There are countless books devoted to normative theories in ethics, and to Utilitarianism and Kantian ethics in particular. In section 6 of these materials details of good and readily available resources are provided. These remarks will be confined to the provision of a general overview of the of these two theories (the identification of their defining features); a brief discussion of some of the key concepts associated with the theories; and a reading list. Bentham and Mill The names most commonly associated with Utilitarianism are Jeremy Bentham, its originator, and John Stuart Mill, its most famous proponent. Bentham’s most important work is Principles of Morals and Legislation (1789), while Mill’s moral and social philosophy is found in the essays Utilitarianism (1861) and On Liberty (1859). Both were political reformers. To Bentham goes the credit of suggesting that existing political institutions need to be critically examined rather than taken for granted. Moreover, the yardstick by which to measure an institution was its effects or consequences on the political body as a whole. An institution was deemed good if its effects were such as to bring about the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people. If Bentham was the originator of Utilitarianism, Mill was its most sophisticated advocate. Bentham had thought that a quantitative analysis of pleasure would suffice for political and moral purposes. However, it soon became clear that this would not be enough. If an action is good if it produces more pleasure than pain, then we seemed forced to admit that some actions which seem morally reprehensible are in fact morally acceptable. For example, if the majority of a society get pleasure from enslaving a minority group, then the resulting pleasure will be greater than the suffering of the minority, yet few would call this morally acceptable. Mill tries to deal with this objection to Utilitarianism by introducing the distinction between high and low pleasures, i.e., a qualitative analysis of pleasure. Philosophy: Moral Philosophy (H) 5 Basic Principles of Utilitarianism Utilitarianism is defined by its three main principles. The consequentialist principle: the view that in order to determine the moral status of an act one must look to the consequences of that act. If the consequences are good, then the act itself is good, if they are bad, then the act is bad, and so on. (This principle clearly differentiates Utilitarianism from Kant’s moral theory more on this later.) The hedonist principle: the view that pleasure is the only thing that is inherently good, while pain is the only thing that is inherently bad. The principle of equality: the view that each individual’s pleasure is worth as much as the pleasure of any other individual. When these principles are taken together they result in: The Greatest Happiness Principle: the view that we ought to perform actions which tend to produce the greatest overall happiness for the greatest number of people. (‘happiness’ and ‘pleasure’ are taken to be synonyms). These are the crucial components of Utilitarian theory. The ‘greatest is more important than the happiness of everyone else’. It is against this background that one can argue that a law or policy reform is morally acceptable only if it suits society as a whole. This universal aspect to moral thinking is often taken to be a condition that any moral theory must recognise. Moral demands and standards apply equally to all individuals. With this characterisation of Utilitarianism complete, we can now comment briefly on some of its key concepts. Utilitarianism, Consequentialism and Teleology It is easy to confuse and conflate ‘teleology’, ‘consequentialism’ and ‘utilitarianism’. For the sake of clarity it is worth pointing out that consequentialism is the genus of which utilitarianism and teleological ethics are species. Any theory is consequentialist if it asserts the consequentialist principle noted above, i.e., that the results of an action determine (or are at least relevant to) its moral status. Utilitarianism is a consequentialist theory because it holds that an action’s moral status is determined by the amount of pleasure or pain it tends to produce. But one can be a consequentialist without being a utilitarian – the easiest way to achieve this is to deny that pleasure is the goal of all moral action (denial of the hedonist principle) while substituting something else as the goal, say, human flourishing, as teleological theories are wont to do. Philosophy: Moral Philosophy (H) 6 It is worth pointing out as well that ‘telos’ has Aristotelian connotations, while ‘utility’ is very much a term associated with the likes of Bentham and Mill. But the divide between these two camps is not as clear cut as some might think. Depending on how one defines ‘pleasure’, one can end up sounding very Aristotelian indeed, as does Mill in On Liberty. In order to make the qualitative distinction between ‘high’ and ‘low’ pleasures, and to then place a higher value on the ‘high’ pleasures, Mill has to go beyond the hedonist principle and find some other criterion by which to privilege high pleasures at the expense of low pleasures. It is not far fetched to say that a notion of ‘human flourishing’, or something similar, is brought in to play this role. The Hedonistic Calculus If one is to judge an action by the amount of pleasure or pain it produces, then one will need some means of measuring or quantifying amounts of pleasure and pain. But how does one determine, or calculate, whether an act has produced more pleasure than pain? Bentham tried to identify the features of pleasures that make one pleasure preferable to another in order to formulate a hedonistic calculus. He argued that intensity duration certainty of attainment nearness or remoteness (of the pleasure) fecundity (the chances of getting the same pleasure again) purity (the chances of a pleasure’s not being followed by a similar pleasure) and the number of people who can enjoy it are the features we need to consider when attempting to calculate the amount of overall happiness an act is likely to produce. As mentioned above, Mill added another element to this discussion with his emphasis on the quality of pleasures rather than on sheer quantitative considerations. He distinguished between high and low pleasures, the latter being the pleasures we share with the animals (for example, eating and sex), the former being the more cultivated pleasures associated with civilised life (for example, going to the opera or reading Homer). Mill’s point was that a life full of animal pleasures was not to be preferred to a life of the higher pleasures (Utilitarianism is not a license for debauchery). He went so far as to say that it is better to be an unhappy human than a satisfied pig. The point of this distinction was not to be elitist, but to avoid the problem Bentham’s purely quantitative analysis encountered concerning the tyranny of the majority. Philosophy: Moral Philosophy (H) 7 ‘Act’ Vs ‘Rule’ Utilitarianism This is a basic distinction drawn by most utilitarians under pressure from certain counter-examples. One might argue that each individual act must be judged on the nature of its consequences. This is act-utilitarianism, and it is closely related to situation ethics which holds that there are no moral rules of thumb that can be safely applied in all contexts, and that each moral situation must be dealt with in its own terms. Rule-utilitarians, on the other hand, argue that our attention should be focused on more general rules of action, rather than particular acts. At issue here is whether acting in accordance with the rule will in the long run tend to produce good or bad consequences. This allows one to say that a particular act in accordance with a rule might, in a particular case, produce a predominance of pain over pleasure, but be acceptable nonetheless because adherence to the rule tends to produce more pleasure than pain over a suitably large number of instances. Standards Objections to Utilitarianism (1) A constant source of trouble for the utilitarian is the measurement of pleasure and pain. For all the distinctions and considerations mentioned by both Bentham and Mill, it has never been clear that utilitarians can provide an accurate measurement of pleasure. How many units of pleasure are to be attributed to, say, playing golf, as opposed to going to the movies? A further serious difficulty with the hedonistic calculus is that it assumes that one can predict with reasonable accuracy just what the consequences of a particular act will be. This assumption would be feasible if moral contexts were ‘controlled environments’, as is the case with scientific laboratories where all the relevant factors surrounding an experiment are known. But life is not a controlled environment, and consequently prediction is a very hazardous endeavour indeed. Nor is it obvious how one is to justify the qualitative distinction between high and low pleasures without bringing in considerations that go beyond the three main principles outlined at the beginning of this section. One might be able to make this distinction if there is some further goal that actions are supposed to have in view. For example, the teleologically minded consequentialist might say that human flourishing, not pleasure per se, is the real goal of human action. And it might be argued that certain pleasures, the high ones for example, are more important for the attainment of human flourishing than low pleasures. But this option is not open to the classic utilitarian because the hedonist principle has been abandoned. Philosophy: Moral Philosophy (H) 8 (2) A second standard difficulty with utilitarianism is that it appears to sanction the slogan that the ends justify the means. Utilitarians appear to be committed to the view that if the ends are acceptable, it doesn’t matter much how they are brought about. For example, the majority in a society may do very well by exploiting a minority for some purpose or other. Few would see this as morally acceptable, and it bothered Mill as well. His essay On Liberty sets limits on the power of the majority, represented by the government, to interfere in the lives of private individuals. But given his utilitarian framework he cannot simply say that to interfere in the lives of private individuals is wrong: he must show that it is wrong because it leads to unacceptable consequences even for the majority. This is anything but straightforward, and there are clear tensions between Utilitarianism and On Liberty for precisely this reason. 3.3 Things to Consider 1. Explain how the greatest happiness principle incorporates the consequentialist, the hedonist and the equality principles. 2. Do you think it is possible to grade pleasures? Why does Mill introduce the distinction between high and low pleasures? Is he just an elitist? 3. How far do you agree with the hedonist principle? Give reasons for your answer. 4. Explain the distinction between act and rule utilitarianism. 5. Show how this distinction operates in a real moral situation e.g., how would act and rule utilitarians respond to the execution of a war criminal who had been convicted of genocide? 6. A philosopher once asked the rhetorical question, “If the ends don’t justify the means, what does?” How would you respond to this question? Philosophy: Moral Philosophy (H) 9 Philosophy: Moral Philosophy (H) 10 4. KANT’S ETHICS 4.1 Outcomes By the end of this section you should : Be familiar with the basic principles of Kant’s Ethics Be familiar with the standard objections to Kant’s Ethics. 4.2 Information Section Preliminary comments These remarks will be confined to the provision of a general overview of the defining features of Kant’s project; a brief discussion of some of the key concepts associated with it; and a reading list. Kant’s Project in Moral Philosophy Kant’s avowed intention is to provide a theory of moral judgement that makes no reference to consequences (he rejects both utilitarianism and teleologically based ethics), or to God. The leading theories of his day made both these appeals, but for various reasons Kant could not bring himself to do the same. Appeals to consequences like the production of pleasure suffered from the appearance of subjectivity and relativity. After all, what one community likes now may bear little resemblance to the likes and dislikes of other communities, and Kant wanted to preserve objectivity in moral judgements. He could not appeal to God as the ground of objectivity because in his Critique of Pure Reason he had shown that all proofs for God are necessarily unsafe. Human beings cannot claim knowledge of anything beyond possible experience, and God is beyond our experience. Moral philosophy therefore cannot rely on theological beliefs. But if consequentialist and theological considerations are rejected, not much remains but human reason itself. Kant’s task is to show that moral judgements could be justified by appeal to principles of reason alone. Kant’s ethical theory is rather difficult for a number of reasons. The first is that it is anything but clear that Kant is able to formulate a theory of moral judgements that makes no reference to God or to the consequences of actions, for he often makes appeal to either God or to consequences (see ‘Difficulties’ 2 and 4 below). This makes it difficult at times to differentiate Kant from other ethical thinkers. Philosophy: Moral Philosophy (H) 11 Furthermore, as O’Neill points out in her contribution to Blackwell’s Companion to Ethics, there is Kant’s Ethics (what Kant wrote in the 1780s and 90s) and then there is an unfavourable version of Kant’s ethics that, while much discussed, has little to do with what Kant actually wrote. Finally there is ‘Kantian ethics’, i.e. theories inspired by Kant, but differing in important respects nonetheless (Rawls springs to mind). It is important then to bear these distinctions in mind when tackling Kant’s ethics. These support materials will deal only with what Kant wrote himself in Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals (1783) and the Critique of Practical Reason (1787). These brief introductory comments complete, we can now turn to the exposition of Kant’s Ethics. His key notion is the famous categorical imperative. The Categorical Imperative The first thing to establish concerning the categorical imperative is that it is a second order principle - that is, it does not guide action directly by telling us what to do; rather it is used to determine which maxims ought to guide our actions. Second, it somewhat confusingly comes in five ostensibly quite distinct formulations. The first formulation of the categorical imperative recalls the notion of universality discussed in the previous section. Kant says ‘Act only on the maxim through which you can at the same time will that it be a universal law.’ There are a number of things to note: First, as stated above, the categorical imperative identifies not actions that one can perform, but maxims that one can adopt as principles of action. In other words, it is a second-order principle. Second, the categorical imperative insists upon the condition of universality alluded to already. Nothing can count as a moral principle if it does not apply to everyone. And finally, the most difficult aspect of the imperative to make intelligible, the clause concerning what one can will to be a universal law. The first two points are relatively straightforward. But what constraints are placed on what one can will? The traditional reading of Kant is that the constraints placed on the will are rational constraints - as indeed they must be to fulfil Kant’s program. Usually the idea seems to be that one cannot adopt non-universalisable maxims because in some sense they are self-defeating, or self-contradictory. Philosophy: Moral Philosophy (H) 12 The case of false-promising may be helpful here. One ought not to make false promises (promises one has no intention of keeping) because one could not will this to be a universal law. If it were a universal law the practice of false promising would not be possible – no one would ever accept anyone’s word, a crucial precondition of the institution of promising. Note that it is not argued that the consequences of false promising are undesirable; nor is any appeal made to the commandment forbidding lying. The point is that false-promising is in some sense self-defeating. The second formulation of the categorical imperative is phrased in terms of means and ends, and respect for persons. Kant says one must treat ‘. . . humanity in your own person or in the person of any other never simply as a means but always at the same time as an end.’ This seems to be a different principle altogether from the first formulation of the categorical imperative, but Kant thinks they are virtually identical in that they both arguably sanction and prohibit the same maxims. It might also be said that one must treat others as ends and respect their humanity in order that they can observe the first formulation of the categorical imperative. Rather than focusing on maxims of behaviour, this version of the categorical imperative enjoins us to safeguard the ability of others to act themselves, and so to safeguard their ability to act in accordance with universalisable maxims. Acting ‘out of duty’, in ‘accord with duty’ and ‘from inclination’ The core idea of Kant’s Ethics is the demand that one base one’s life and actions on the rejection of non-universalisable maxims. This leaves open just how one observes this injunction. Kant recognises that one may act in accordance with a universalisable maxim for various reasons. One may so act from genuine regard for the universal maxim itself, and so act ‘from duty’. But many will act in accordance with a universalisable maxim from fear of what would happen if they did not. Here we have a case of outward conformity to duty, or an act that ‘accords with duty’. Since we are never in a position to determine the motivations of others (including ourselves?) it would appear that outward conformity to duty is all one can insist upon. Finally, a truly moral action must be done with some reference to the universalisable maxim- if one acts in accordance with a maxim simply because one is so inclined (because it is pleasant) but with no consciousness of the maxim, then this is not yet a fully moral action. The distinction between duty and inclination allows Kant to underline the fact that we should not take what is pleasurable to us, or good for us, as the mark of the moral, for it may not be pleasant for everyone. But it is also worth pointing out that acting from duty and acting from inclination are not always in tension – one’s duties and inclinations can be compatible, although they very often aren’t. Philosophy: Moral Philosophy (H) 13 Difficulties with Kant’s Theory (1) Universalisability is not sufficient for morality. There are many maxims that are universalisable but which carry no moral implications. For example, I may wish to eat a healthy diet. I can also will that this becomes a universal law. Yet it does not seem to be a breach of any moral obligation should someone decide they prefer a diet of fish and chips. (2) The constraints placed on the will are vague. Sometimes there is an appeal to the notion of self-contradiction. But on other occasions Kant seems to suggest that a maxim is objectionable if, once universalised, it produces a state of affairs that is unacceptable to rational people. A number of problems emerge with the second suggestion. First, there is an appeal to the consequences of acting in accordance with the maxim, which smacks of consequentialism. Second, the problem is now to state what ‘rational’ people find acceptable. To do this will require a criterion of rationality, a notoriously difficult concept (Kant works on lines that eventually inspired Rawl’s veil of ignorance). Third, Kant assumes that all rational people (once they have been identified) will find the same situations unacceptable. An argument for this is needed. Finally, Kant needs to make the connection between rationality and morality. Even if we can identify ‘the rational people’, and even if they all find the same things unacceptable, one is still left with the problem of justifying the maxims on which they act. Hegel argued that ‘the Rational is the Real’; Kant appears to be saying that ‘the Rational is the Good’. Neither is self-evident. (3) Let us accept for the sake of argument that Kant’s categorical imperative identifies our duties. But what is one to do in cases where one’s duties come into conflict with each other? A hierarchy of duties is required in order to avoid conflicting obligations. This is not a knock-down argument against Kant, but a lacuna in the theory exists which needs to be filled. (4) Finally, Kant assumes that a condition of moral behaviour is freedom. Human beings are moral agents because they are free, and hence responsible for their actions. But it is far from clear that Kant can accommodate the freedom of human agents with his metaphysics and epistemology as laid out in The Critique of Pure Reason. The natural order is dominated by the laws of nature, i.e., it is determined. But man is part of the natural order, so he too is determined. If so, he cannot be free, and hence cannot be a moral agent. To escape this difficulty Kant makes appeal to a radically dualist view of human beings. The natural/phenomenal self is determined; but the moral/noumenal self is beyond the laws of nature. This dualism is not popular amongst philosophers today. Moreover, to make sense of beings that occupy both the natural and moral orders, Kant is forced to postulate both a benevolent God and an immortal life where moral virtue and happiness coincide. These appeals to theological notions are not only unacceptable to current philosophers, they seem to go against the very project that Kant had set for himself. Philosophy: Moral Philosophy (H) 14 4.3 Things to Consider 1. What is Kant’s project in moral philosophy? 2. State two versions of the categorical imperative. 3. What does ‘second-order’ principle mean? 4. How far do you agree that human beings ought never to be treated merely as means? 5. Why is it not enough to act from inclination if your inclinations are good? 6. What is the relationship between being rational and behaving morally? Philosophy: Moral Philosophy (H) 15 Philosophy: Moral Philosophy (H) 16 5. ISSUES IN APPLIED ETHICS 5.1 Outcomes By the end of this section you should be familiar with Utilitarian and Kantian approaches to the issues of Voluntary Euthanasia Punishment The Morality of War. 5.2 Voluntary Euthanasia Before considering how Utilitarians and Kantians might approach the issue of voluntary euthanasia, a few standard distinctions ought to be mentioned. Euthanasia, which means literally ‘a good death’, from the Greek eu (good) and thanatos (death), comes in various forms. But all have the following features in common: all forms of euthanasia involve: (a) the deliberate termination of a life, and (b) the termination is carried out for the sake of the person whose life is being terminated. That said, it is customary to distinguish between voluntary, non-voluntary, and involuntary euthanasia: 1. voluntary euthanasia occurs when a person requests their own death; 2. non-voluntary euthanasia occurs when the person is unable to make this request for themselves (persons in a coma, for example); 3. involuntary euthanasia occurs when the person could have given or withheld consent to the termination of his/her life, but did not do so, either because he/she was not asked, or having been asked actually withheld consent. We will confine our interest here to voluntary euthanasia. It is also common to distinguish between active and passive euthanasia. 1. Active euthanasia implies intervention, a speeding up of the arrival of death. 2. Passive euthanasia, by contrast, is more a matter of non-intervention, a withholding of treatment, a letting die. Finally there is the distinction between direct and indirect euthanasia. 1. Direct euthanasia occurs when the method of bringing about death aims only at bringing about death (‘mercy killing’). Indirect euthanasia, by contrast, occurs when death is brought about as a sideeffect of treatment (for example, an over dose of certain drugs will reduce pain - a form of treatment - and bring about death). Philosophy: Moral Philosophy (H) 17 This distinction is sometimes expressed in terms of intention: in direct euthanasia bringing about death is the intention, whereas in cases of indirect euthanasia death is merely foreseen. Whether this distinction can be maintained is a matter of some dispute. Each distinction is meant to mark a morally significant category. Whether this is the case is of course a matter of dispute. While there is general agreement that the distinctions between voluntary, non-voluntary, and involuntary do mark morally significant categories (even if all forms are ultimately unacceptable), the last two distinctions are more problematic. Is responsibility really evaded in cases of passive euthanasia? What is the moral difference between an action and an omission in cases of euthanasia? Furthermore, is there a moral distinction between what one intends to bring about by one’s actions, and what one foresees will be the effect of one’s actions. Clearly the Utilitarian will have difficulties employing this distinction; but is the Kantian in any better position? Utilitarian Considerations Utilitarians are committed to the promotion of happiness and the alleviation of suffering. So it would seem at first sight that cases of voluntary euthanasia pose no particular moral difficulties. Since requests for death are usually made by those whose suffering is deemed by them to be unendurable, or, on balance, to make prolonged life more painful than an early death, the principle of utility would sanction the granting of this request. This could at least be the position of the Act-Utilitarian. The situation is complicated, however, by the fact that the Utilitarian must have an eye to the over-all happiness of the greatest number, and not just to the condition of the individual requesting death. For while the suffering of the person requesting death is terminated by euthanasia (a good), the practice of euthanasia might have undesirable consequences for society at large. Many have argued that legalising any sort of killing is the thin edge of the wedge. Once voluntary euthanasia has become an accepted practice, will it not be easier to slide into other, less ‘acceptable’, forms of euthanasia? If life in and of itself is not necessarily a good, and the quality of life becomes the crucial issue, people may come to feel that they can pass judgement on the quality of another’s life, and then act accordingly (this certainly happened under Hitler). Moreover, will the acceptance of this practice not put pressure on the old and infirm to consider euthanasia when they would otherwise not do so? Philosophy: Moral Philosophy (H) 18 These are the sorts of issues the Utilitarian must face when attempting to give a verdict on the moral status of voluntary euthanasia. Fortunately for the Utilitarian, there is a body of experience to call upon when making these decisions, the Netherlands having legalised voluntary euthanasia back in 1973. Kantian Considerations Kant himself does not discuss the issue of voluntary euthanasia; but he does have views on suicide, and many see the issues as equivalent. He states that ‘man cannot have the power to dispose of his life.’ Kant argues that suicide is morally unacceptable because it violates the second version of the categorical imperative, namely, never to treat oneself or any other human being only as a means and not as an end. His line is that in committing suicide one is treating oneself as a means and not as an end. It is not clear that this line is entirely coherent. If treating someone as an end means acting with a view to their interests as opposed to our own, a definition which seems reasonable enough, then it is not obvious how suicide, or voluntary euthanasia, is in principle morally unacceptable. If one is acting in accordance with someone’s expressed wishes, then one is treating them as an end, and not a means. Indeed, part of the definition of euthanasia is that it is carried out for the sake of the person requesting it. Clearly one might want to prevent someone in a particular case from carrying out voluntary euthanasia on the grounds that they are not fully aware of certain pertinent facts (like a new cure just discovered last week). But such cases are not voluntary, since to act voluntarily is to act with full awareness of the pertinent facts. Kant might respond by saying that such wishes are not rational, and as such violate the first version of the categorical imperative. On this line, treating someone as an end requires only that one act in accordance with their universalisable wishes. But does voluntary euthanasia violate the first version of the categorical imperative? This question amounts to the following: Is the universalising of voluntary euthanasia self-defeating or self-contradictory? It is not clear that it is. If everyone is given the right to ‘dispose of’ themselves when they see fit, does this lead to a situation wherein one is unable to dispose of oneself when one sees fit (as is the case with false promising)? Or does voluntary euthanasia contravene another duty that is universalisable. If so, what is it? Of course it is entirely possible that Kant’s moral theory cannot generate all the moral judgements he would have liked. Voluntary euthanasia may be a case in point. Kant, like many Christians, may have felt that the taking of life is the privilege of God alone. But it is far from clear that his moral theory and his moral intuitions are compatible in this case. Philosophy: Moral Philosophy (H) 19 5.3 Punishment When the criminal justice system punishes offenders, it deprives the criminal of certain goods. Sometimes it is only a quantity of money, but very often they are deprived of their freedom. In certain cases they are even deprived of their life. What justifies punishment? And how does one decide the nature of the punishment to be meted out on each occasion? These are the issues that occupy us here. Note that we are not looking at the causes of crime (although these might be relevant in some cases) but at how criminals should be treated. There are three leading theories of punishment: the utilitarian theory the retributive theory (adopted by Kant) and the reform theory. Punishment by Utilitarian lights is bad in and of itself since it involves the infliction of suffering. But it is justified (when it is justified) on account of its good consequences. These consequences are: (a) the deterrence of recidivism (committing a crime again) (b) the deterrence of those yet to enter a life of crime from doing so, and (c) its incapacitating power – it places criminals where they cannot do any more harm, i.e., in jail, or, in extremis, in the grave. The retributive theory of punishment, on the other hand, insists that punishment is justified because the criminal deserves to be punished, whether or not the punishment has good consequences. This theory is often associated with the Old Testament line, “An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth.” Both theories are thought to suffer from serious, if not fatal, flaws. The Utilitarian is in the uncomfortable position of having to sanction the punishment of the innocent if the consequences of this punishment were thought to be good for society as a whole. This violates our intuition that punishment should be visited only on the guilty. The retributive theory, on the other hand, insists that only the guilty should be punished, for only they deserve to be punished. But since punishment is to be justified without reference to its good consequences, its sole purpose seems to be the satisfaction of the (primitive?) desire for revenge. If this is the case, then punishment is tinged with what many consider to be unsavoury motives which undermine the moral status of the act. Philosophy: Moral Philosophy (H) 20 A third theory of punishment is that it is carried out with the intention of reforming the offender. This theory is consequentialist in tone because it stresses the good consequences of punishment if carried out properly. But it also supplies what many consider to be a more civilised motive for punishment. Part and parcel of this theory is the view that offenders are ill, not morally depraved, and require treatment rather than punishment. This view is usually accompanied by the claim that the offender is in fact a victim of society – that society itself is as much to blame for the offence as the criminal. But civilised as this theory may appear, many find it degrading and potentially dangerous. On the one hand, it deprives the criminal of the dignity associated with personal autonomy. The criminal is not seen as a free agent, but wholly determined by forces beyond his control. By not punishing in the retributive sense, one no longer treats the criminal as a human being who is responsible for his actions, but more like a misbehaving dog who has yet to be properly trained. On the other hand, treating the person as ‘ill’, and seeking to reform his behaviour might amount to no more than brain washing and social control. This form of punishment/treatment deprives the criminal of the right to decide what type of person he wishes to be. Moreover it is open to abuse by governments which decide to extend the concept of ‘illness’ to cover the politically undesirable. How many political activists were jailed as mentally disturbed in the Soviet Union? Philosophy: Moral Philosophy (H) 21 5.4 The Morality of War When, if ever, is war morally permissible? And if it is permissible in certain circumstances, what constraints, if any, are placed on the means used to prosecute that war? These two questions are central to ethical thinking about warfare. The first question requires what is called a theory of jus ad bellum (concerning what ends justify engaging in war), the second a theory of jus in bello (concerning the means). There are several theories which address these issues. The first, which is hardly a moral theory at all, states that war is acceptable if it is in the national interest. This is an amoral position because moral matters are not considered relevant to the determination of what is in the national interest. This is the attitude to war adopted by the representatives of most nation states, and is mentioned only to be dropped. A second theory is Pacifism, the view that no wars are morally acceptable. Various reasons may be given for this view. Some pacifists hold that no violence is acceptable under any circumstances, while Kant is vexed rather by the fact that war leads to the deaths of innocent people (see below). The third view, associated with utilitarianism, is that some wars are morally justifiable (see below). Finally, there is the Just War theory associated with Aquinas but developed by many other thinkers. We will confine our attention here to the views of Kant and the Utilitarians. Kant is uncompromising in his condemnation of war because it inevitably entails what he feels he must condemn, namely, the punishment of the innocent (see preceding section on punishment). The innocent include civilians, the inevitable victims of modern ‘total war’, as well as the soldiers of both armies, most of whom have committed no crime other than to find themselves conscripted by their respective governments. The punishment of the innocent is unacceptable because it violates the two versions of the categorical imperative. Killing soldiers and civilians for the sake of some further end (whatever that end might be) is to treat them as means alone, a violation of the second version of the categorical imperative. Moreover, punishing the innocent for the crimes of their leaders is not universalisable, says Kant, because it entails what cannot be rationally assented to, namely that I could find myself punished when totally innocent of any wrong doing. [Note that while this is indeed undesirable, it implies a contradiction only if one is a retributivist concerning punishment.] Now since there are no just wars, the question concerning what means can be employed in the prosecution of that war does not arise. Philosophy: Moral Philosophy (H) 22 The Utilitarian position can already be divined. The Utilitarian would not condemn all wars, pace the Kantians. The Utilitarian looks at the consequences of any given war. And while the Utilitarian is in principle against actions that increase suffering, the suffering caused by a given war must be balanced against the suffering caused by its not being prosecuted. Consequently, the Utilitarian must judge each war on its individual merits, rather than issuing a blanket condemnation as the Kantian or Pacifist is wont to do. In the case of the inevitable and foreseeable deaths of innocents, the Utilitarian might say that, although this is not generally acceptable practice, it is justified if the consequences of not attacking are worse. But having said that some wars are morally justifiable (those that produce a greater balance of pleasure over pain), what means are permitted in warfare? Is all fair in love and war? As mentioned in the information section on Utilitarianism, one of the common criticisms levelled against it is that it sanctions the view that the ends justify the means. In other words, if the war does lead to a greater amount of happiness overall, then whatever means were employed to prosecute that war are acceptable. This is an uncomfortable position for most, given the litany of war-crimes and atrocities that usually accompany wars. But the Utilitarian might respond that warcrimes play no part in the winning of the war, having no military purpose, and so cannot be justified by the fact that the war itself brings a greater balance of pleasure over pain. Only those acts which serve these ends are justified. However, most current thinking about the morality of war places itself within the tradition associated with Aquinas. The Just War theory cannot be entered into here; but it is worth mentioning nonetheless because it does show up the limitations of both the Kantian and Utilitarian theories with respect to the morality of war, both appearing to be rather blunt weapons indeed. It is also worth noting that while most nation states conduct wars with a view to their own national interests, the language used by politicians to justify wars to the general public is that of Just War theorists. They are usually concerned to point to the justice of the cause (protection of smaller states from aggressive neighbours; forcing compliance with international law – the Gulf War; or the prevention of humanitarian disasters and the defence of human rights – Kosovo). They also stress how the war is prosecuted – the careful avoidance of nonmilitary targets with ‘smart-bombs’; use of power commensurate with the task, etc. Philosophy: Moral Philosophy (H) 23 5.5 Things to Consider 1. Explain the difference between (a) voluntary, non-voluntary and involuntary euthanasia (b) active and passive euthanasia (c) direct and indirect euthanasia. 2. To what extent do you think the legalisation of voluntary euthanasia will inevitably lead to other forms of euthanasia? Give reasons for your answer. 3. Why should someone be refused a ‘good death’? 4. Outline the three leading theories of punishment. 5. Are offenders morally depraved, or victims of society? Support your decision. 6. Of the leading theories, which do you think is the most ‘humane’, and why? 7. What is the distinction between a theory of jus ad bellum and a theory of jus in bello? 8. How far do you agree with the Kantian view of condemning all warfare? 9. A utilitarian can claim that some wars are morally acceptable. To what extent do you agree with the utilitarian about this? Philosophy: Moral Philosophy (H) 24 6. SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER READING Primary Texts Mill, J.S. ‘Utilitarianism’, in On Liberty and Other Essays. Great Britain: OUP, 1991. Kant. I. Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals. Translation by Paton as The Moral Law. London: Hutchison, 1953. Secondary Texts The following are just a few of the many works worth consulting. Crisp, R. Mill: On Utilitarianism. London: Routledge, 1997 (from the Routledge Philosophy Guidebook series) Frankena, W. K. Ethics. New Jersey: Prentice-hall, 1973. (Foundations of Philosophy series) Morton, A. Philosophy in Practice: An Introduction to the Main Questions. Oxford: Blackwell, 1996. Palmer, M. Moral Problems: A Coursebook for Schools and Colleges. Cambridge: The Lutterworth Press, 1998. Raphael, D.D. Moral Philosophy. Oxford: OUP, 1985. Scruton, R. Kant. Oxford: OUP, 1982. (Past Masters series) A Companion To Ethics. Edited by Peter Singer. Oxford: Blackwell, 1997. (The Blackwell Companions to Philosophy series) Warburton, N. Philosophy: The Basics. London: Routledge, Philosophy: Moral Philosophy (H) 25 Philosophy: Moral Philosophy (H) 26 7. GUIDANCE ON READING AND WRITING PHILOSOPHY This unit requires a close reading of significant philosophical texts. Since philosophical texts are unlike most texts you will have encountered, a few guidelines on how to read them are in order. Read the prescribed texts. Primary texts are difficult, but there is no substitute for reading the author in his/her own words. You cannot rely simply on commentaries, although these will likely be indispensable as well. Take your time. Careful reading cannot be rushed, and this is doubly so in philosophy. Individual learning styles certainly differ: some people function best by reading the same text several times patiently with progressively more detailed attention; others prefer to work through the text patiently and diligently a single time. In either case, encourage yourself to engage the text at a personal level. A final point: philosophical texts are very dense. Do not attempt to read for long periods at a stretch. Consider the context. Philosophical writing arises from a concrete historical setting. Approaching each text, you should keep in mind who wrote it, when, for what audience, what purpose it was supposed to achieve, and how it has been received by the philosophical and general communities since its appearance. Spot crucial passages. Most philosophical texts vary in density from page to page, and it isn’t always obvious what matters most. (The context will provide clues to this.) With practice you will soon be able to highlight the most important passages. Identify central theses. Each text is intended to convince us of the truth of particular propositions. Although these central theses are sometimes stated clearly and explicitly, authors often choose to present them more subtly in the context of the line of reasoning by which they are established. Remember that the thesis may be either positive or negative, either the acceptance or rejection of a philosophical position. Locate supporting arguments. Philosophers do not merely state opinions but also undertake to establish their truth. That is, the author will offer premises that are clearly true and then claim the a sound inference from them leads to the desired conclusion. You will probably learn to recognise the most common patterns from early examples in your reading. Assess the arguments. We are obliged to accept the conclusion only if it is supported by valid inference from true premises. Thus, there are two different ways in which to question the soundness of an argument: (a) are the premises true? (b) is the inference valid? Philosophy: Moral Philosophy (H) 27 Look for connections. Since these texts occur within a tradition, they are often directly related to each other. Consider the ways in which each philosopher incorporates, appropriates, rejects, or responds to the work of those who have gone before. Within your reading of a particular philosopher, notice the way in which material in one section of the text links up with material in another. Finally, make every possible effort to relate this text to what you already know form courses in other disciplines and form your own experience. But above all, don’t worry! You will spend most of your class time going over the assigned readings, often in great detail. You will have plenty of opportunities to learn what other readers have found, to ask questions for clarification, and to share your own insights. As the unit proceeds, you will grow more confident in your own ability to interpret philosophical texts. Writing Philosophy Write to learn. Expressing your thoughts on paper is an excellent way of discovering what you really think. Even if you are the only one who ever sees the results of your efforts, putting them in writing inevitably clarifies them. Some suggestions: Understand the assignment. Whether writing on an assigned topic, or one of your own choosing, you must have a clear grasp of your aims. Focus on a single issue; be clear about your answer to it; state explicitly what your thesis is; and identify your arguments for that thesis. If your single issue is best divided into smaller sections, treat each in turn, and then show how your answers in each section cohere into a thesis which responds to the central issue. Interpret fairly. Most of your assignments will involve the interpretation of classic texts. Before you can write sensibly about the text you must understand it. Before you criticise anything, make sure you understand what is going on. A helpful hint: if something in the text strikes you as totally ludicrous, you have probably missed something. Classic texts are not free of errors; but they would not be classics if they contained blindingly obvious blunders. Support your thesis. Anyone can have an opinion. But as philosophy students you are required to argue for your point of view. Do not claim anything that you cannot argue for, or anything you do not believe will be accepted by all parties to the dispute. Consider the alternatives. Make sure you consider the arguments on the other side. If your thesis fall to one of the standard argument for the opposing thesis, then you had better have a way of meeting that objection. Omit the unnecessary. Identify what is strictly relevant to your topic and the defence of your thesis, and remove all other considerations from your written work. The presence of irrelevant material, and ‘padding’, show that you are not able to see what is important and what is not, and this detracts from the persuasive power of your writing. Philosophy: Moral Philosophy (H) 28 Make it your own. Do not copy big chunks of text from books; quotes are fine, but should not be overdone. Refer to the names of philosophers you are talking about but express their ideas in your own words as far as you can. Use a variety of sources rather than one old favourite. Write clearly. It is your responsibility as a writer to express yourself in a way that can be understood. Use specific, concrete language whenever you can. Define your terms and use them consistently throughout the paper. Understanding of what you have written will be improved if you follow all of the foregoing instructions. Finally, you may find it useful to have a audience in mind when you write. Do not write just for your teacher or lecturer. Try writing the essay as if it was for your friend. This will force you to think very clearly indeed about the order of presentation of the material, and how to express it in your won words. Writing Essay Exams Be prepared. Rely upon the study questions distributed at the outset of the unit and in the support materials. Use these questions to guide your reading of the text as they will highlight what is significant. If you have considered the issues fully, nothing on the exam itself can surprise you. Arrive on time, and try to be well-rested and relaxed. Understand the question. Do not just begin writing. Read each question carefully, and make sure you answer the question. It is also a good idea to write out a short essay plan before beginning to write in earnest. Stick to the point. Answer the question asked, and do not do off on a tangent. Do not write everything you know about the philosopher or the text in question. Again, you must be able to identify what is relevant and what is not. Inclusion of irrelevant material detracts from the quality of the essay. Use your time wisely. You will be asked to write several essays. Divide the time equally among the essays (if weighted equally) and return to an essay if you have more to say once the others have been completed. Do not get bogged down or absorbed in one essay at the expense of the others. One brilliant essay will not make up for 3 poor ones. Make every word count. Quality, not quantity, should be your motto. Write clearly, but do not be concerned with writing beautiful prose. Philosophy: Moral Philosophy (H) 29 Philosophy: Moral Philosophy (H) 30