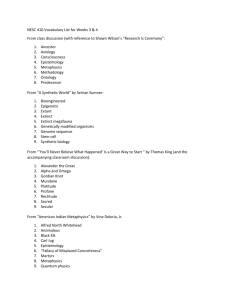

RMPS Metaphysics Intermediate 2 5069

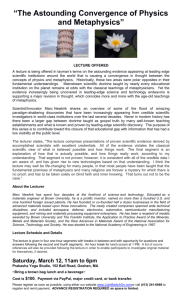

advertisement