Quality Assurance in Child Welfare A Framework for Quality

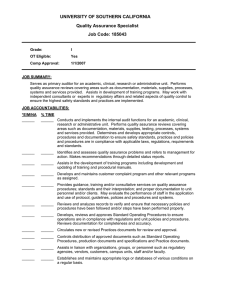

advertisement